Women who Love Women: Fragments from Egyptian Cinema

12.png

Photos from the film Habibi El Asmar (1958)

One of the most absurd things about watching Banat Al Youm (1957)1 is seeing two sisters fight over a guy. Salwa, who is in love with her sister’s fiancée Khaled, is mad at Layla for not devoting all her time to her betrothed and instead going out roller skating with her friend Bosayna that Khaled doesn’t like. Bosayna and Layla are portrayed as bad girls for partying, not wanting to have children and for valuing their friendship over romantic pursuits. When Layla complains to Salwa that Khaled does not want her to see her friend anymore, her sister responds in an almost commonsensical tone, as if already knowing the answer, “so what? What matters more to you, your friends or your fiancée?”

Such strife between women on screen is far from arbitrary. Egyptian cinema is full of scenarios of women sabotaging other women’s relationships out of spite, wives and mothers fighting over the attention of men, women eavesdropping and trash talking their neighbors and women ratting out their friends to get ahead. This persistent “girl on girl crime” footage can best be understood by situating it in a wider entwined history of gender oppression and capitalist formation.

In a brilliant chapter from Witches, Witch-hunting and Women, Silvia Federici traces back the distortion that the word gossip went through, from “a term commonly indicating a close female friend turned into one signifying idle, backbiting talk, that is, talk potentially sowing discord, the opposite of the solidarity that female friendship implies and generates”(Federici,2018:35)2. She recounts how in a post-enclosure3 modern England, women gathering with their ‘gossips’ in taverns for hours on end to drink and enjoy each other’s company were a direct threat to the consolidation of patriarchal authority and the nuclear family. Female friendships and solidarity amongst women were to be destroyed through religious sermons that preached obedience to husbands, popular songs and plays denouncing the meeting of gossips, circulating laws that outrightly forbid it and torture instruments like the ‘gossip bridle’4 forcing women to denounce each other in witch trials. Along with the trivialization of women’s labor in the household also came the devaluation of women’s social lives. What was once as sign of female solidarity and intimacy between women turned into “idle women’s talk”5.

In what really couldn’t be described except as a rant about Egyptian women, Qassim Amin conveys anxieties about closeness between women at the dawn of the construction of a modern Egyptian state:

“Our women have become accustomed to idleness; they consider it a necessity of life. […] While with friends and neighbors, her deep sighs ascend with the cigarette smoke and coffee steam as she talks loudly about private concerns; her relationship with her husband, her husband’s relatives and friends, her sadness, her happiness, her anxiety, her joy. She pours out every secret to her friends, even those details associated with private behavior in the bedroom” (Amin,2008:33)6.

For Amin, the prototype of a modern woman that Egyptian women should aspire to become, is a woman wary of her surroundings, one that “conceals her thoughts from those closest to her”. A woman that steers away from “situations which excite her toward inappropriate issues”7 lest they interfere with her housework.

In what follows I’d like to amplify those “exciting” situations. So dangerous that they are entangled with idleness or brought to the fore in films only to serve as cautionary tales. I am interested in moments of intimacy between women in Egyptian pop culture; the kind of intimacy that makes you wonder: are they girlfriends or gal pals? By reading into things, highlighting and taking fragments of encounters and relationships between women out of context, I subscribe to a genre of “queer fantasy”, in line with what Muñoz refers to as “the utopian force of aesthetics”8 (Muñoz, J. 2010:132). This sort of bricolage where we’re creating something out of what is available at hand, is in a way a queer praxis that goes against normative narratives of love. The fragments that I will be talking about are “images that […] represent the potentiality of another reality”9. Writing about “queer utopian aesthetics”, Muñoz speaks of their conjuring powers, ushering us towards potentiality that is not yet there. Women in these fragments found themselves very drawn to each other, sought solace in one another when life was unbearable. To bring attention to intimacies between women in these films, teleological arcs, narrative coherence and men are left out of focus.

On a less serious note, these fragments have post-ironic meme potential. They trespass to the realm of relatability, and embody a ‘mood’.

Fragment #1: Samra and Zakeya

Every now and then before going to bed, Samra (Samia Gamal) waits by her window eagerly to catch a glimpse and wave at Zakeya (Taheya Carioca), the famous dancer who strolls in with her car when she comes to visit her mother. Samra has a fiancée, played by Shoukri Sarhan, but at the start of the film10 she doesn’t seem to care about him that much. She is fascinated with Zakeya and in one of the earlier scenes of the film, is fantasizing about dancing with her.

12.png

Photos from the film Habibi El Asmar (1958)

11.png

A shot of Samra yearning

Samra lives with very strict parents who would rather she stay in her room instead of going out and wish to marry her off to stop worrying about her expenses. She occasionally manages to sneak out to see Zakeya perform at the club. Watching the film, you can’t really blame Samra for the crush she’s developed on Zakeya. Taheya Carioca at the time was in her femme top extraordinaire phase. She was corrupting her young lovers in her roles, distracting them from schoolwork and from their fashioning into reputable productive citizens. And quite frankly all the boys and girls wanted to be corrupted by her (see also Shabab Imra’a, 1956). Like the characters in Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives11, she was a rebellious woman whose stubborn desire to do as she pleases and to live a life seeking pleasure was transgressive; she is killed off at the end of the film to give way for a happy ending for Samra and her fiancée. Halfway through, the film takes a weird turn where Zakeya pimps out Samra and there’s a diamond smuggling affair going on but still it is hard to unsee the excitement Samra felt around Zakeya, especially with an unremarkable performance from Shoukri Sarhan. For Samra, Zakeya represented a certain joie de vivre that she aspired to but that remained a fantasy, the stuff of dreams.

10.png

Taheya Carioca looking like she can step on your neck

9.png

Samra and Zakeya greeting each other after Zakeya’s dance

Fragment #2: Hend and Kamilia

Ahlam Hend w Kamilia (Dreams of Hend and Kamilia 1988) is another film12 about yearning. Hend and Kamilia, two lower class women who migrated from rural cities to work as maids in Cairo, are tied by a beautiful friendship. Their relationship is the only thing that is constant in their lives, they get married, divorced, leave their jobs and take on new ones all while finding solace in one another. Kamilia had realized after her brother married her off to his superior, that marriage is a form of unpaid labor (“ خدمة ببلاش ”). She consistently dreams of sharing a flat with her friend Hend. She often talks about wanasونَس whenever she is talking about her relationship with Hend, indicating a sort of blissful companionship. Hend stays with Kamilia and her husband after one of the families she worked for accuses her of stealing. Not long passes before Kamilia’s husband kicks both of them out and they end up squatting in an unfinished building. In one scene, we see Kamilia day dreaming of a better life, imagining that one day they could live in one of the flats of this building. When Hend gives birth and her husband is in jail, Kamilia decides to name the child Ahlam, giving homage to their shared dreams. They get into a lot of trouble and shenanigans together; they find the money Hend’s husband has hidden and decide to go on a long-awaited trip to Alexandria but end up getting robbed by their driver and stranded on a deserted road. The film ends with a scene of them looking for Ahlam who is standing near the sea waving at them and they both run towards her and embrace her.

picture_1.png

Hend ecstatic at the sight of Kamilia on the bus

6.png

Hend and Kamilia greeting each other on the bus

5.png

Hend and Kamilia at the amusement park

4.png

Hend, Kamilia and Ahlam by the sea

Fragment #3: Mariam and Sahar

I’ve seen Dantella13 (1993) many times, mostly to watch Yousra perform her fabulous musical numbers but I am always struck by the heartwarming relationship between Sahar and Mariam. The film starts with a flashback of Sahar saving Mariam from drowning, back when they were both little girls. At the beginning of the film, Mariam was a young wealthy girl around 10 years old vacationing in Alexandria and Sahar, a show girl that performed in the circus with her family. Sahar saving Mariam was a defining moment and the start of a lifelong friendship. After Mariam finishes her law studies in Cairo, she moves to Alexandria to live with Sahar, who is now working as a singer and dancer in second-rate cabarets. Mariam manages to always get Sahar out of trouble, for instance in one scene, she bails her out when she’s arrested for drunk driving. Mariam is more reserved and part of her admires how impulsive and full of life Sahar is. Sahar wishes that Mariam could have more faith in herself and see herself the way she sees her. If we imagine them together, Mariam would be book smart gf and Sahar would be street smart gf. The bond they have is temporarily threatened when they fall in love with the same man who ends up marrying them both. Their pranking and teasing during that period however is clearly about how angry they are at each other and not necessarily out of jealousy. After a car crash that she interprets as a wake up call, Sahar decides that this is not right and towards the end of the film they both end up leaving Hossam and raising Mariam’s daughter together. Both Dantella and Ahlam Hend w Kamilia inadvertently end with the possibility of queering kinship. In both films, we see women going against the normative nuclear family ideal. This perhaps might not always be by choice as in the case of Ahlam Hend w Kamilia but it goes to show that reality is already much more complex than the traditional capitalist heteronormative imaginary of the family.

3.png

Mariam reading to Sahar

2.png

Sahar and Mariam at the beach with their daughter

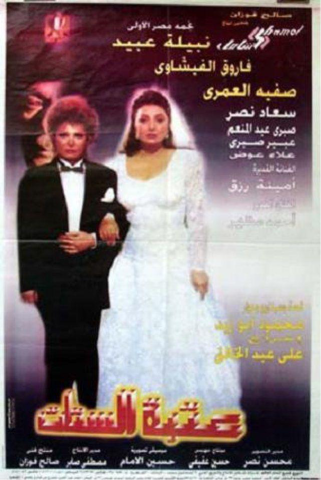

Fragment #4: the poster from Atabet el Setat (1995)

I found this poster by absolute chance while scrolling through the filmography of Safeya El Emary. What struck me are the aesthetics of the poster, there is no ridiculous comic de geste implying that this is so wacky thus reinforcing its impossibility (what you would expect from a more contemporary production). It’s a photo of two women posing as partners, with all seriousness as if it was taken on their wedding day. Unfortunately, I haven’t seen the film14 since I couldn’t find a decent version of it online but the blurb tells us that it is about a woman (Nabila Ebeid) who was gaslit by her husband into thinking that she can’t give birth and who then decides to go to a witch (Safeya El Emary) to help her get pregnant. The image lends itself easily to misinterpretation, it is hard to imagine what the creative director was thinking when they picked this scenario for the poster. We can assume that it might have intended to convey the emasculating power of witches or an anxiety about men’s impotence but that doesn’t mean that we can’t have fun with this image.

An ending note on queerness, love and friendship

To build queer worlds is, amongst many things, to challenge the supremacy of romantic love. Queer and feminist theorists have consistently pushed us to expand and redefine limited understandings of love, intimacy and pleasure that we’ve grown up with under capitalism, and to confront the failure of imagination at the core of what Adrienne Rich refers to as ‘compulsory heterosexuality’15. To build queer worlds, is to seek love beyond normative confines, to think of “friendship as a way of life”16 as Foucault envisioned. It is to redefine the erotic as Audre Lorde taught us as that which provides “the power which comes from sharing deeply any pursuit with another person”17. This entails “the sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual” with another person.

This photo essay was about women who love women, the affection, tenderness, companionship, joy, admiration shared between them. It is about the trouble it stirs for “our rather sanitized society”18 which can’t imagine passionate intensity except in relation to the modern concept of the couple. In dwelling on fragments that blur the lines between camaraderie and romance, it is also about the possibility of queerness that lingers in a yearning look, in gentle embraces, shared moments of joy and accidental aesthetics that momentarily interrupt the heaviness of the world.

- 1. The film is directed by Henri Barakat and features Abdelhalim Hafez, Magda and Amaal Fahmy in the respective roles of Khaled, Salwa and Layla. The scenario is written by Youssef Issa, you can find out more about its plot here on Wiki Gender.

- 2. Silvia Federici, “On the Meaning of Gossip,” Witches, Witch-hunting and Women (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2018), 35. Federici explains that the root of the word, consisting of “Old English terms God and sibb [...] originally meant godparent” and was used to refer to companions in childbirth

- 3. Federici writes about a material context following the seizure and privatization of common land that had previously been the source of livelihood for many people. The enclosing of land—what Marx had referred to as primitive accumulation and ‘the original sin of capitalism’--forced peasants to sell their labor to survive. The loss of the commons led not only to the loss of earlier forms of subsistence that women relied on but also the exclusion of women from wage earning labor and property ownership to confine them to the domestic sphere.

- 4. ibid., 39.

- 5. ibid., 41.

- 6. Amin, Q. & Peterson, S.S. 2000, The liberation of women and The new woman: two documents in the history of Egyptian feminism, The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

- 7. ibid, p. 34

- 8. Muñoz, J. E. 2010, Cruising utopia: the then and there of queer futurity, American Library Association dba CHOICE, Middletown.

- 9. ibid, p.134

- 10. Habibi El Asmar is a black and white film that came out in 1958, it is directed by Hasan El-Saifi and written by Mahmoud Ismail.

- 11. Hartman, S. V. 2019. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. First edition. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

- 12. Directed and written by Mohamed Khan and starring Naglaa Fathy, Aida Riyad and Ahmad Zaky, the film received praise for its portrayal of relatable and complex women as opposed to earlier melodramatic representations rendering women as helpless victims, for more on this, check out this link on Wiki Gender

- 13. Dantella is a film directed by Enas El Degheidy and written by Syrian screenwriter Rafik El Saban.

- 14. Atabet el Setat is a film starring Nabila Ebeid, Safeya el Emary and Farouk el Fishawy. It is directed by Ali Abdelkhalek and written by Mahmoud Abu Zeid.

- 15. Rich, A., 1980. Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Signs: Journal of women in culture and society, 5(4), pp.631-660.

- 16. Foucault, M. & Lotringer, S. ed. 1989. Foucault Live: Interviews 1961-1984. New York: Autonomedia. The formulation by Foucault first appeared in an interview with the French magazine Le Gai Pied in April 1981

- 17. Lorde, A.. 1978. Uses of the Erotic : the Erotic as Power. [Distributed by the Crossing Press].

- 18. Foucault, M. & Lotringer, S. ed. 1989. Foucault Live: Interviews 1961-1984. New York: Autonomedia. p. 136.