Palestinian Feminism in the Time of Erasure: Body, Voice, and Symbolic Resistance in Gaza

Coming from a background in science and audiovisual production, Presica Chaar has worked across Lebanon, Iraq, and Turkey in project and grant management, supporting feminist, media, and grassroots groups in complex political and social contexts. Her engagement with civil society has been less about career than about inquiry – a sustained questioning of how structures shape meaning, collaboration, and fatigue. Within that trajectory, she has contributed to research, coordination, and project and strategy design, gradually moving away from iNGO frameworks to work more closely with small collectives and grassroots initiatives concerned with gender, media, and accountability. Her current interests move between film, photography, and critical writing, and through dialectics explore how image and language can hold space for contradiction, fragmentation, and care. Having long navigated the NGO industrial complex and its alienation, she now studies cinema and explores a multidisciplinary visual practice. Presica continues to work between languages and disciplines as a photographer, photojournalist, translator, and writer, seeking forms of collaboration and expression beyond institutional structures.

This translation seeks to preserve the original’s interlacing of academic tone, feminist critique, and lived affect. I intentionally retained certain Arabic concepts (zaghroodeh, archiving body, aid-based hegemonies, etc.) without full domestication to maintain their political and cultural resonance. The English text mirrors the Arabic structure and rhythm closely, with only minimal interventions for clarity and coherence. I have avoided embellishment and over-translation, prioritising conceptual fidelity and the voice of the author over idiomatic fluency. The tone aims to reflect the blend of anti-colonial feminist research, reflective journalism, and the embodied register of testimony that defines the original text.

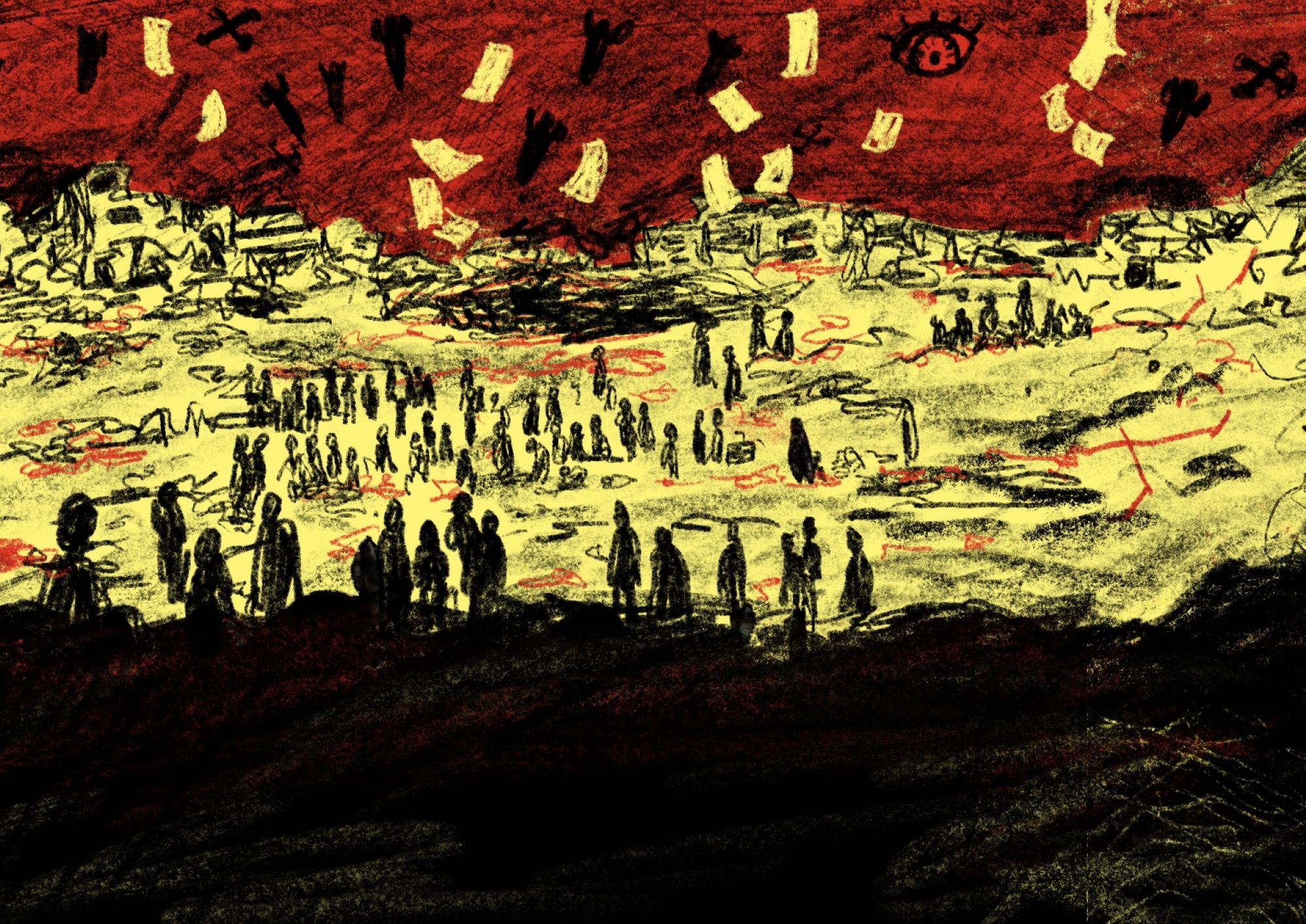

failure_of_humanitarianism.jpg

Myra El Mir

Within the ongoing colonial context where instruments of material violence intersect with mechanisms of symbolic violence, the Palestinian female body – particularly in the Gaza Strip – is continuously reconstituted as a dual site of annihilation and resistance. Far from being a mere biological entity, this body is positioned as both a symbol representing national existence and as a living archive for the meanings of continuity and endurance in the face of erasure policies. The large-scale Israeli assault since October 2023 and the ongoing genocide in Gaza expose this structure, whereby women have been targeted directly not as collateral damage but as structural components within the social and cultural fabric.

UN Women (2024) has estimated that women and children constitute over 70% of the victims of this genocide. This comes amid systematic bombardment of health infrastructure – including maternity wards and fertility clinics – and reflects a deliberate colonial strategy aimed at demolishing the reproductive and social capacity of Palestinian society. Within these semiotics, motherhood is forcibly transformed into a form of political resistance whereby the female body is divested of the very conditions of continuity, and instead reconstituted as an instrument of resilience against genocidal logic. Yet, this pervasive presence of the female body within bloody scenes of loss, rescue, and digital documentation remains confined to complicit discourses on representation.

On the one hand, a reductive humanitarian framing strips Palestinians of political context, rendering them victims devoid of agency. On the other hand, an Orientalist narrative reduces the Palestinian body to a binary of the submissive victim or the idealised icon of struggle, devoid of complexity. Both discourses – media and academic alike – contribute to the erasure of Palestinian feminist knowledge that arises from lived experience under colonialism and siege, despite the central role that women actively play in archiving catastrophe and producing resistance discourse. This epistemic gap reveals the limits of dominant narratives and underscores the need for a new critical language that moves beyond reductive visual representation and the systemic neglect sustained by academic discourse.

In light of this reality, a central research question emerges: How is the Palestinian female body represented within the context of contemporary colonial violence, and what forms of symbolic resistance do Palestinian women produce to counter the material and symbolic policies of erasure? This research question unfolds into several analytical dimensions: the first explores mechanisms of digital resistance and self-narration during the occupation's assault; the second examines how policies of erasure take shape in women’s everyday experiences as captured through testimonies and field interviews; the third traces the contributions of anti-colonial feminist critique to interpreting media and academic representations of Palestinian women; and finally, the fourth reconsiders the body itself as an instrument of archiving and resistance within the colonial genocidal project.

Since the 1948 Nakba, the Palestinian female body has been a central site of struggle. The early archives of exile recount how women became bearers of the memory of the refugee camps and of mass exile, as sexual violence and forced displacement were deployed as instruments for collective humiliation. During the First Intifada (1987–1993), arrest campaigns and home demolitions constituted a direct targeting of women, while human rights organisations documented instances of childbirth at military checkpoints due to denial of passage. During the 2008–2009 Israeli assault on Gaza, the bombing of maternity wards and reproductive care centres constituted an extension of what Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian has termed “reproductive violence,” wherein the female body is targeted not as an incidental victim but as the bearer of Palestinian social continuity. It has become clear that what continues to unfold under the genocide is not an isolated event but a recurring episode in a long colonial history that positions the female body as a site of both erasure and resistance.

This paper proposes a conceptual framework – the archiving body of erasure and resistance – which conceives of the female body as a political and epistemic agent that produces an alternative discourse through everyday practices, acts of care, digital documentation, and collective memory. In this way, the body is no longer confined to the binary of victim versus icon, but is redefined as an archival structure that resists colonialism through knowledge, language, memory, and collective rage, opening new horizons for rereading the Palestinian feminist experience within the context of the colonial catastrophe.

Gender as a Colonial Tool in the Palestinian Context

At the heart of the Palestinian struggle, the gender and colonial dimensions intersect. Palestinian women’s bodies become a central arena of confrontation between structures of domination and acts of resistance, moving beyond questions of biology or social identity into a deeply political and cultural field. Gender is deployed as a colonial tool to reshape local communities and impose hegemonic narratives that disguise themselves under the banners of “women’s liberation.” This is what Lila Abu-Lughod (2013) calls imperial feminism – the instrumentalisation of Palestinian women’s suffering to legitimise political and humanitarian interventions while effectively silencing their voices and erasing their lived experiences.

This colonial use of gender intersects with Judith Butler (2009) in Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable?, who theorises the notion of grievable life. Butler shows how colonial discourses determine whose lives are considered worthy of mourning and who is denied full humanity. In the Palestinian case, women are often reduced in Western media to anonymised statistics, rendering their bodies invisible and unworthy of survival. In this sense, acts of feminist documentation and expression become political practices that redefine Palestinian life as one that is visible and historically recordable.

In this context, Gayatri Spivak (1988) reminds us in the foundational text “Can the Subaltern Speak?” that the marginalised are not permitted to speak except through elite intermediaries who reshape their discourse. This is evident in the case of Palestine, where women’s voices are often reduced to a rhetoric of pity or portrayed as neutral victims. Meanwhile, Palestinian women on the ground produce narrative knowledge from within the siege and bombardment, turning acts of writing, documentation, and expression into practices that break the colonial hegemony of silence. On this reduction, Lila Abu-Lughod (2013) explains in Do Muslim Women Need Saving? how Western discourse reduces Muslim women and reproduces them as victims devoid of agency – a dynamic clearly visible in Gaza, where women are presented only as symbols of suffering while their roles in community and organisational life are erased. This analysis opens the door to a deeper understanding of the female body as a bearer of resistance rather than a symbol of weakness.

Saba Mahmood (2005), in Politics of Piety, goes further by redefining agency so that it is not confined to liberation from religion or social norms; rather, women can exercise agency from within religious and social commitment. Through this framework, Palestinian women’s motherhood, care, and the documentation of their pain can be read as acts of resistance no less significant than direct political participation. Rana Barakat (2017), meanwhile, emphasises the notion of embodied memory, in which the body itself becomes a bearer of history and resistance – inseparable from land and memory.

Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian (2015; 2023) adds another dimension by advancing the concept of reproductive violence, whereby the Palestinian female body is targeted through attacks on hospitals and maternity wards in an attempt to weaken the social structure. If Palestinian bodies are sites of domination and erasure, they also generate new spaces of symbolic resistance, particularly in the digital realm. Through social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok, everyday testimonies become a collective memory that counters attempts at symbolic erasure and redefines the presence of Palestinian women within the global sphere – not as silent victims, but as active agents inscribing a living history that challenges colonialism in all its manifestations.

Symbolic Resistance: Ululations and Digital Archiving

The Palestinian zaghroodeh (ululation) is no longer a mere folkloric remnant or a passing ritual revived on occasions of death; it has become a metapolitical act that transcends the boundaries of joy and grief to establish a renewed meaning of existence in the face of genocide. A woman who ululates at a funeral does not simply defy mourning but performs what resembles a rewriting of death within the collective record, transforming the individual wound into a communal sign and absence into an intensified presence. Since the Nakba, and through successive uprisings, the female voice has continued to pierce the public sphere like an aerial blade, declaring that loss is not an ending but another beginning, and that mourning itself can be reclaimed as an act of resistance that anchors memory rather than consign it to disappearance.

Yet, the time of genocide in Gaza has dismantled this entire scene: there are no longer funerals to organise, no processions overflowing with crowds, chants, and revolutionary songs. What was once a collective act charged with symbolism has collapsed under the conditions of burial beneath bombardment, of mass graves, and of a death that no longer allows the ritual to complete its symbolic cycle. The zaghroodeh here did not fall silent only as a sound; it has been transformed into a fractured metaphor, an absent echo that recalls what can no longer be enacted, yet continues to burn as the memory of an impossible resistance that illuminates the realm of imagination.

Here, the digital sphere emerges as an alternative space for ritual: trembling images cut from the moment, live streams running alongside explosions, women’s writings interwoven with tears and virtual ululations. These spontaneous signs do not constitute only documentation; rather, they accumulate into a counter-archive that restores to memory its right to endure and establishes an alternative language that confronts colonial attempts at erasure. It is a form of symbolic resistance that transforms the threatened body and the besieged voice into tools for dismantling the discursive structure of power and for reconfiguring the political space itself. As Butler (2009) notes, such acts – however marginal or small they may appear – carry a deconstructive force capable of unsettling the symbolic architecture of power and of redistributing the boundaries between what is celebrated and what is meant to be buried in silence.

Building on a critical engagement with feminist and anti-colonial literatures, this paper proposes the archiving body of erasure and resistance as a locally grounded conceptual framework. The paper is not a field study in the conventional sense but a theoretical reflection that rearticulates concepts from within the Gazan context. The body is understood as a living archive that not only documents moments of survival and loss but also reproduces memory through trace, scar, voice, and care, so that everyday practices, from emotional documentation to breastfeeding a child under bombardment, become archival acts of resistance against erasure. Unlike Butler, who stopped at the right to grief, this framework proposes a shift toward the historicisation of pain (Archivable Pain): from the right for life to be mourned to the right for pain itself to be archived.

Through this approach, the female body is no longer a biological or symbolic domain but a political document that resists erasure and challenges international discourses that celebrate the “victim” while overlooking the historian. This framework also opens a horizon for reading acts that may seem marginal – such as filming corpses or standing firm before the camera – as archival forms of resistance, repositioning Palestinian memory within the body itself rather than in the official national archive that has long marginalised women. However, the – still working – concept acknowledges its own limits. It requires an expansion of scope to include the diaspora and the multiple contexts of feminist memory, as well as deeper engagement with archival studies and sensory anthropology. It also calls for caution against the trap of glorifying or commodifying pain. Nevertheless, the concept’s strength lies in its capacity to interrogate not only the tools of colonialism but also the research methodologies that have long separated the body from knowledge and pain from politics.

The archiving body of erasure and resistance is not only a concept but a proposal for a new critical horizon, one that rewrites the relationship between the Palestinian body, history, and memory. It produces an alternative form of knowledge that resists both colonial and aid-based hegemonies and lays the foundation for a living archive that pulsates with life in the face of oblivion.

Counter-Archiving as an Act of Resistance

In digital contexts, the posts documented by women were not only emotional expressions or moments of personal confession; rather, they collectively embodied what can be described as a counter-archival practice carried out by women from within the catastrophe, not from its margins.

Bisan Odeh1 is a young woman from Gaza who lost her home and was forced to seek refuge in multiple places across the Strip during the genocide. When she wrote on her Instagram page: “My room – twenty years of my life – is gone,” she was not writing to mourn but to remain, to transform the destroyed space into a living memory rewritten on virtual walls. This sentence, which might seem like a fleeting emotional reaction, carries an archival function: it turns the demolished place into a living memory, redrafted within the digital sphere. Writing here is not limited to documentation; it becomes a form of symbolic resistance that reproduces place as a collective narrative, preventing its burial beneath the rubble. Moreover, Bisan’s daily documentation of Israeli atrocities – filming women in displacement camps as they gather children into morning lines for lessons, broadcasting clips that call on peoples to rise up against their complicit rulers – renders her discourse a living archive of resistance against digital erasure and against the occupation’s attempts to silence the voices that expose it before the world.

Mais (27) says: “I wrote on Facebook that my son didn’t sleep all night. I felt as though I were carving a small memory that defies erasure.” (2024). This daily writing dismantles slow violence, revealing how time itself is reclaimed through language and through the scar digitally archived. These acts go beyond simple survival under bombardment; they rebuild language and expose the boundaries between pain and knowledge, turning Gazan feminist writing into an archival act that resists oblivion.

Documentation as a political act has fostered an acute awareness that narration does not only save; it fights. The Western media silence – which Anitta Kynsilehto (2024) has described as a form of “complicit feminist denial” – is not met only with screams but with archiving (Nassar, 2024). Every post, every image, every trembling voice constitutes a material dismantling of the colonial representational system, as formulated by Spivak (1988), wherein women are permitted to speak only when speaking of their deaths, not their knowledge.

Yet, Palestinian feminist resistance extends beyond documentation. It finds its most vivid expression in care as resistance – a practice that may appear familiar at first glance yet carries a political agency largely absent from the lenses of media and academic discourse. When Ayat Khaddoura2 says, “Women are each other’s support,” she redefines feminist solidarity as a local, decentralised political act that resists the disintegration of social structures through everyday care. Umm Layan recounts: “We shared the bread among us—no one ate alone… I felt that this solidarity was stronger than any weapon” (2024). These testimonies, documented by women on their personal social media pages, demonstrate that the Palestinian woman does not resist in spite of her social roles but through them. Acts of care – cooking, cleaning the martyr’s grave – all become strategic practices that resist erasure and lay the foundations for an alternative collective memory.

Saba Mahmood (2005) describes the capacity for agency from within tradition, where everyday acts of care – from cooking food to tending to children – become strategies of political endurance that resist both oblivion and the social fragmentation pursued by colonialism. Rana, a university student from Gaza, says: “Every time we hear that a hospital has been bombed, I feel the bombing isn’t just against us… as if it were against our future.” (2024)

Within this context, a stark contradiction emerges between the living archive produced by women and the fractured scene reproduced by the media. Discourse analyses reveal that Palestinian women are depicted across most Western media channels either as mourning mothers or fragile bodies awaiting care, echoing Butler (2009) on the hierarchy of grief: not every life is considered grievable. Conversely, even as some Arab media outlets seek to highlight women’s everyday forms of resistance, their discourse remains confined to the binary of heroic motherhood and collective symbolism, thus effacing the individual feminist voice behind collective heroism (Ihmoud, 2025).

Here, the significance of the concept of the archiving body emerges as an analytical tool that repositions feminist action within its true context – not as a by-product of war but as a structure of resistant knowledge production. Women engage in documentation not to move beyond grief but to preserve it as political memory, as shown in Palestinian women’s testimonies and interviews. This practice transcends analyses that focus solely on the bodily effects of genocide without deconstructing the symbolic dimension produced by women from within.

Within this theoretical continuum, revolutionary motherhood – as exemplified by Doaa al-Baz – is not only an act of care but a project of resistance that redefines the very meaning of life itself. Al-Baz3 declares: “I am a mother to the resistance,” as though she were rewriting the concept from its roots: motherhood is no longer an instinctive need but a site for reorganising society after erasure. Likewise, Fidaa – who buried her husband and distributed aid with the same hands (2024) – embodies this proposition: that every female body in Gaza is an archival site in the making.

This paper coins the concept of the archiving body of erasure and resistance not only in response to the absence of a just discourse but as an original Palestinian feminist contribution that reclaims concepts to their true positions: the humiliated body, the silenced voice, and the everyday practice that refuses silence.

What this paper reveals goes beyond questioning representation or analysing symbols; it lays the ground for an emerging Palestinian feminist discourse that redefines concepts not through prior theorisation but through lived testimony. The notion of the archiving body is not only an attempt to understand pain but to construct a tool of dismantling that interrogates colonialism and counters it through language, scar, care, and anger. When written about, this body is not only recalled but sustained, inscribed with a memory that resists oblivion, etched upon the walls of narrative not only as a scar but as a map of survival.

Abu-Lughod, Lila. (2013). Do Muslim Women Need Saving? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Barakat, R. (2017). “Writing/righting Palestine studies: settler colonialism, indigenous sovereignty and resisting the ghost(s) of history.” Settler Colonial Studies, 8(3), 349–363.

Butler, J. (2009). Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? London: Verso Books.

Ihmoud, S. (2025). “Countering Reproductive Genocide in Gaza: Palestinian Women's Testimonies.” Native American and Indigenous Studies, 12(1), 33–53.

Kynsilehto, A. (2024). “Feminist silences and silencing the critique of Gaza genocide.” Gender, Place & Culture, 32(10), 1467–1476.

Mahmood, Saba. (2005). Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. (2015). “The Politics of Birth and the Intimacies of Violence Against Palestinian Women in Occupied East Jerusalem.” The British Journal of Criminology, 55(6), 1187–1206.

Shalhoub-Kevorkian, N. (2023). “Reproductive Violence in Palestine: The Need for a Feminist Approach to Justice.” Opinio Juris. https://opiniojuris.org/2024/02/01/reproductive-violence-in-palestine-the-need-for-a-feminist-approach-to-justice/

Spivak, G. C. (1988). “Can the Subaltern Speak?” In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, Nelson & Grossberg (Eds). Urbana/Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 66–111.

UN Women. (2024). Gender alert: The gendered impact of the crisis in Gaza. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2024/01/gender-alert-the-gendered-impact-of-the-crisis-in-gaza

أم ليان. (2024). شهادة شخصية. مقابلة شخصية، غزة.

رنا. (2024). شهادة شخصية. مقابلة شخصية، غزة.

فداء. (2024). شهادة شخصية. مقابلة شخصية، غزة.

ميس (2024). شهادة شخصية. مقابلة شخصية، غزة، محفوظة في أرشيف الباحثة.

نصار، هبة. (2024). تحليل 20 مادة إعلامية (تقريرات، أخبار، مقاطع مرئية، أو تصريحات رسمية)، تم جمعها من مصادر إعلامية ناطقة بالعربية والإنجليزية. محفوظ في أرشيف الباحثة.