The Failure of Humanitarianism: Money and Praxis at the End of Times

failure_of_humanitarianism.jpg

Myra El Mir

Context

It is impossible to summarise the indiscriminate violence and atrocities committed by the zionist settler colonial state against the people of the land of our region since 1948, or the similarities and differences between the Palestinian and the Lebanese realities under said occupation. Drawn at colonial tables, our borders and the fragmentation of our region have, on the one hand, disrupted our continuities of belonging, and on the other, asserted a shared anthology of subjection to the colonial and genocidal violence of western empires – whose ongoing projects of domination, displacement, and erasure have made resistance the very condition of existence in our region.

As a result of the expanding Israeli aggression, mass displacement from the southernmost towns of Lebanon had already begun in late 2023, in parallel with the intensification of the genocide in Gaza and the West Bank. In September 2024, the heavy aggression expanded the mass displacement from the South and beyond border-towns.

Two nation-wide Pager and Walkie-talkie attacks spread terror across the country on the 17th and 18th of September. They took the lives, eyes, and hands of at least 3400 people1 from different demographics, children included. As of the 20th of September, the zionist offensive targeted the southern suburbs of Beirut, as well as central areas of the city. It led to a boom in displacement and terrorised thousands out of Beirut and its suburbs within a single night (23rd of September). The occupation’s “Northern Arrows” operation was noted2 as the most intense offensive on Lebanon and resulted in the displacement of 90-94k people in a single day as a result of 1600 airstrikes.

By Sep 25th, it was estimated3 that around 600,000 people had been displaced nation-wide, most of whom came from Dahye, the South, and the Bekaa. These areas were the main (but not sole) targets of heavy non-stop bombing and chemical weapons, in an attempt to ensure that people’s lands would no longer be inhabitable/viable.

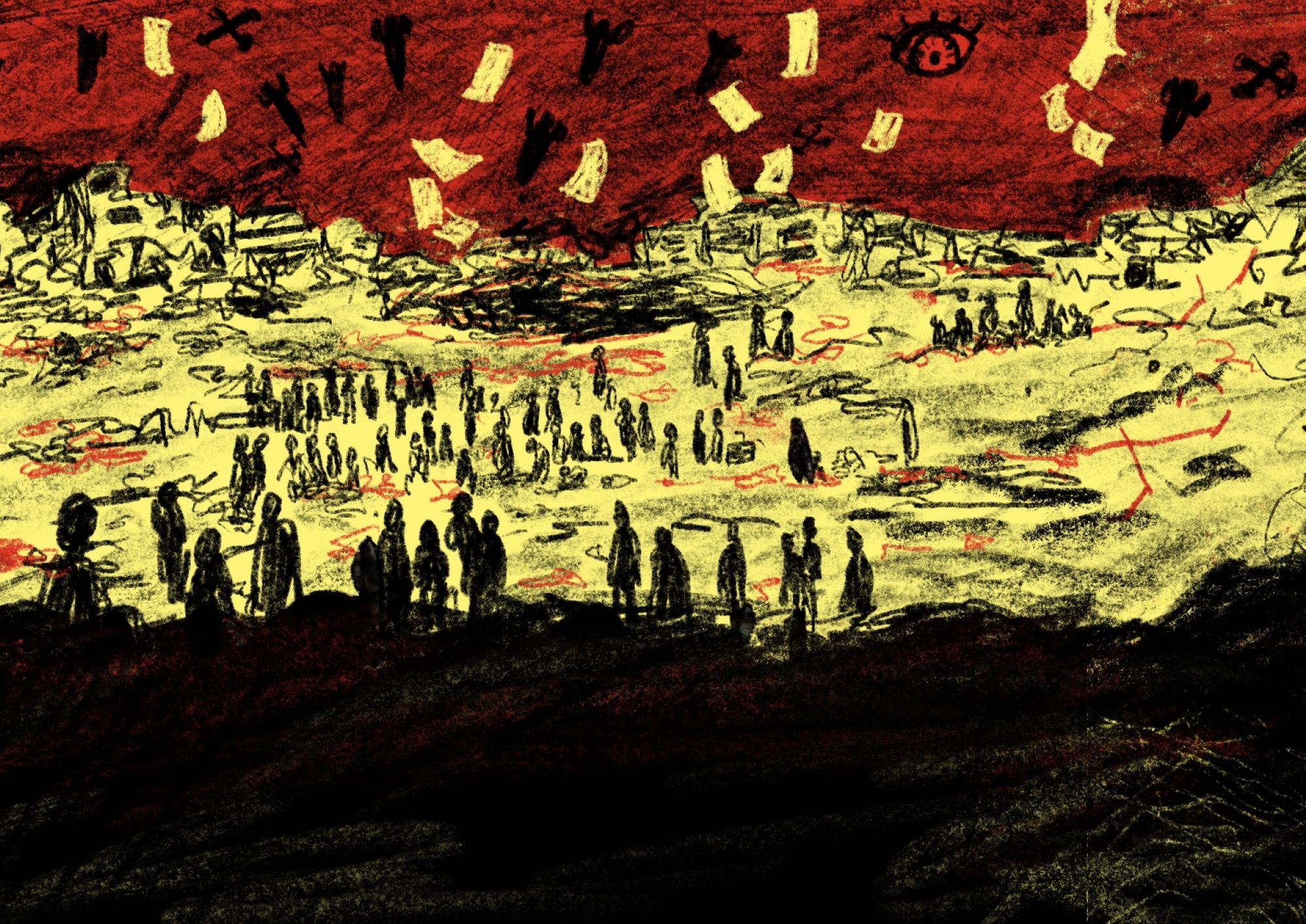

Between the announced ground invasion on the 1st of October and the alleged ceasefire on the 27th of the same month, the culmination of violence was compounded with the impunity and inaction of the Lebanese state (failure to announce a state of emergency, failure to provide basic shelter and aid, etc.). As of the 17th of October, people took initiative, congregated, and attempted to organise in ad hoc groups that operated through WhatsApp communities and gathered in alternative community spaces, outside of the jurisdiction of the state or the existing non-governmental organisations. These were people of all ages and political inclinations: individuals, informal collectives, grassroots organisers, migrant domestic worker groups, and Syrian and Palestinian refugees. Some opened their homes to welcome the displaced; others managed logistics, procured essentials, and shared what little they had. Many were themselves displaced, carrying the same losses they sought to relieve in others. They were not driven by institutional agendas or by the vocabulary of humanitarianism, but by necessity, solidarity, and a refusal to wait for structures that had already abandoned them. Yet, despite all the community efforts and raised funds, there were always just as many families living at the seaside in the open while weather conditions worsened. Governmental divisions that had been set up for the purpose of responding to such catastrophes would not take concrete action for weeks afterwards. In the meantime, the scenes from central Beirut alone were apocalyptic.

Mass displacement also meant that thousands were displaced multiple times and that just as many have not been able to return to their homes. Meanwhile, the gap between what little aid people could put together and the growing number of displaced and their needs widened significantly.

This discrepancy was not new but part of a continuum. During the 2019 uprising, displaced migrant workers were abandoned by their kafeels and forced to sleep in the streets. After the 2020 port explosion, employers/sponsors once again “discarded” domestic workers, leaving them homeless in the middle of catastrophe. These earlier moments set a precedent for how systemic violence reproduces itself in every crisis. The escalation of 2024 was not an exception but an intensification of these ongoing logics of abandonment.

Response

Some of the images that stuck with me were from the peak of the war: thousands and thousands of people – families, individuals, acquaintances of all age groups – were using plastic sheets as makeshift tent set-ups along the seaside road of Ras Beirut, across the coastline, and even on the separating portion of two-lane streets, as cars drove by from both sides. I remember seeing elderly people sleeping directly on the asphalt and cement of the corniche. I remember watching the Internal Security Forces raid these areas, forcing people to move their tents. I remember the “Hamra Star” incident when hundreds were forcefully evicted from an abandoned hotel in West Beirut and into the streets, at the request of the building’s owner.

In the eastern Beirut neighborhoods, displaced Shiite families were routinely denied shelter. They were turned down or discriminated against because of sectarian fearmongering, class prejudice, and xenophobia. Those who could pay faced soaring rent prices: with the increased need for shelter and basic goods, landlords and profiteers monopolized the market, exploiting the desperation of the displaced. This discrimination compounded the violence of displacement: bombed out of their homes, then structurally excluded from re-housing in their own capital.

Instances of physical violence and bullying of the displaced were also reported. Parents pleading for baby formula, elders wandering the streets at night with no mattress to lie on – all were scenes not of incidental suffering but of systematic abandonment, and of systemic and state violence.

Added to all of these atrocious realities, and to put this as blatantly as possible: while the displaced Lebanese were under-resourced and under-supported, other migrant working-class people were severely overlooked, marginalised, and excluded from even the meagerest support that organising communities could provide.

Migrant domestic workers (MDWs) were left to sleep under bridges as their kafeels fled, abandoning them like discarded property. Governmental and private shelters refused entry to even the poorest of the poor amongst migrants, Syrians, and Palestinians. Private or abandoned buildings that sometimes offered refuge to Lebanese families would not host refugees or MDWs. Systemic racism and class discrimination entrenched in the kafala system only intensified in times of crisis, making migrant bodies disposable. This echoed earlier moments of mass “disposal” back from the days of the 2019 uprising and in the aftermath of the 2020 port explosion. The war simply magnified this ongoing structural violence.

In the absence of the state, people attempted to organise in whatever forms they could. Families and acquaintances pooled resources. Community kitchens sprang up. Makeshift transportation was arranged to move people out of conflict zones. Mattresses, baby formula, food, and medical basics were gathered and redistributed. WhatsApp groups became lifelines for coordination. These were not comprehensive responses, but fragmented survival strategies that barely scratched the surface of escalating needs.

As always, institutionalised iNGOs stepped in with their usual logic of distributing mere crumbs of their budgets – often less than what they spend on bureaucracies, staff luxuries, visibility campaigns, organisational structures, and self-congratulatory mechanisms that serve only to validate their existence and spending. These institutions remain profoundly disconnected from the real needs of the people they claim to serve, while their minimal functionality continues to depend on an absurd amount of resources with no prospect of sustainability. Driven by the aesthetics of humanitarianism, their glossy reports measured charity in numbers: parcels distributed, percentages of households reached, governorates covered. They counted, but they could not comprehend the full extent of this reality.

Flow of Money

Smaller, grassroots groups, especially those with a clear, politicised discourse, had already begun losing funding with the rise of the European far right, as humanitarian and developmental agendas were taking on new forms. The Russian invasion of Ukraine was also pivotal to how funds were distributed: by April 2022, EU funding strategies had been reshuffled to prioritise “emergency” allocations within Europe itself, redirecting vast resources toward supporting “fellow Europeans.” This shift cascaded through the entire humanitarian and developmental apparatus, revealing once more how aid follows the racial and geopolitical hierarchies of the west. The white saviour complex simply metamorphosed, no longer rescuing the global south but rescuing whiteness from within, and rendering the SWANA region increasingly irrelevant to what is deemed urgent, fundable, or worthy of saving.

When October 7 unfolded, it only deepened this existing redirection. What had begun as a structural reorientation of European and western aid became a full-blown collapse of support for politically outspoken organisations across the region. The blow to the NGO sector, on which the Lebanese economy had been heavily reliant since 2011, as it had been on foreign funding more broadly, was immediate and devastating.

The remaining small share of funding was allocated to groups with luke-warm, ambiguous discourse. No room was left for the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist. The dwindling of resources for these groups naturally meant that after the expansion of the colonial war to Lebanon, their capacity to engage with the community-led aid efforts was equally limited.

In addition to the aid initiatives, multiple fundraisers were set up, many of which by Lebanese expats and migrants. Since the start of the banking crisis in 2019, during which most depositors lost their funds to private banks, the severe economic crisis boiled down to the local currency losing over 90% of its value to the dollar. Transactions from and to foreign countries have become extremely difficult since, which only intensified the erosion of trust in the banking system. Following October 7, the west’s classification of the state and its people as “Hezbollah and Hamas collaborators” instilled numerous obstacles to receiving financial aid and transactions from fundraisers and expats. The Israeli offensive created further impediments in terms of the flow of funds, allegedly out of fear of funding “Hezbollah groups.”

In Gaza, the blatant blockade turned into a full blown famine under genocide, alongside scandalous incidents of aid (and therefore fund) distribution. This fundamentally changed what aid and humanitarianism look like, exposing patrons and their agendas. In Gaza, models such as the Gaza Humanitarian Fund, an American non-profit under Israeli direction, facilitated the militarisation of aid by setting up distribution centers that would lure famished Palestinians to their deaths. They would either be shot, hunted down by snipers, led into a stampede, or, in recurring incidents, crushed by crates dropped in parachutes. Those who did survive these tools of extermination would either not receive as much as a grain of rice, or in the best case scenario, would end up with expired baby formula and rotting foods they had to fight with their lives for.

These became infamously known as the flour massacres, where people starving under siege were baited into death by the very apparatus of humanitarian aid. The grotesque irony revealed the true nature of “neutral aid:” not a lifeline, but a continuation of siege and extermination by other means. In other words, the aid system in itself, its overlords, agendas, and frameworks are often designed to systemically perpetuate the acts of extermination and ethnic cleansing.

While “official” aid distributors in Gaza were being fully defunded and delegitimised (such as UNRWA), in Lebanon, most funders distanced themselves from this political reality and severed preexisting contracts with their grantees. A few expressed passive solidarity while emphasising their unavailability as funding institutions.

We are beyond expecting accountability and defining justice within the parameters of colonial language. We are disillusioned beyond the point of return by the state of the world and the pathway of humanitarianism. We have found ourselves (as the global south) in the loneliness and alienation of this imposed language. We are beginning to fully comprehend the absurdity of relying on foreign funding: the very system that sustains us only to ensure we remain dependent also limits our capacity to ideate alternatives. Thus, we turn towards what little capital we have left: our communities, our people. Despite our background and ideological difference, we are brought together by an existential threat that has lingered since before imperialism and turned our geographies into nations – an existential threat that has become so audacious that it blatantly announces forced displacement and mass annihilation.

Our Intervention and Process

After October 7, 2023, we at Kohl Journal joined the ranks of several like-minded groups by going on an open strike in order to organise with worker-led and popular movements against the genocide. We suspended our work until January 2024. Expectedly, we lost two thirds of our funding.

The question of funding – relying on western funds, the NGO structure, the promises of impact versus the reality of motionlessness – weighed heavily on us. We attempted to bring together several groups through what we called the “Refuse” initiative, in order to discuss the situation and brainstorm alternatives. Our hope was that we may one day put together a different funding system that would rely less and less on existing structures, operate in a more circular model amongst multiple groups, would not prerequisitely require the groups seeking funding to look like NGOs, and could become sustainable. Our efforts, as well as those of other groups, were scattered, and the initiative was unfruitful. The timing, and how everything had literally drained us, made it less and less relevant to be raising funds for our groups.

What did it mean for us to be writers, researchers, and social scientists at times where genocide, actual genocide, was occurring one hundred kilometers away? What does it mean to dismantle the language of colonialism from behind our keyboards while it continues to literally crush the bodies of our people with its tanks? Powerlessness, beyond the clichés the word encompasses and the commonality of the feeling we currently share with millions across the globe, seeped into our electronic devices one meeting at a time.

With our humble team of five, scattered around the region and Europe, we were stretching our resources thin. We attempted to carry on with what we had under the frameworks we had in place. We followed through with our calls for contributions to our issue on Palestinian realities and hoped that this would still give space for a Palestinian-led discourse, even if that remained within the confines of our screens and virtual worlds.

As all forms of violence against our people grew and further materialised, the language of solidarity became infuriating in itself. The September 2024 escalation of the Israeli genocide in Lebanon came as no surprise. Similar to our communities in Lebanon and abroad, all five of our team members utilised their networks and efforts, both remotely and on the ground, to secure funds and materials for basic survival of the displaced and the affected.

At the time, we were in sparse contact with most of our funders. However, one feminist fund, Mama Cash, was particularly aware of our conditions and those of our communities. They checked in with us repeatedly and offered support to our team members in Lebanon, and aid efforts. We started looking at the groups taking action and the disproportionality of support across displaced communities, to understand where such support could be best utilised.

We did not want to reproduce a humanitarian aid project as defined by the institutional structures we reject. We did not convert any of the raised funds into disposable goods like single meals or hygiene kits. Rather, we wanted to mobilise our individual and organisational capacities to challenge the disjunction between displaced Lebanese citizens, refugees, and migrant workers – people often abandoned by their kafeels, struggling alone in a country built on their exploitation and exclusion. We saw our role as one of intermediaries: we used our networks and administrative leverage to decentralise aid and connect the resources to those who needed them the most, while leaving the use of the money to their discretion.

In terms of consistency with our own politics, the fundraising reflected our refusal to behave like a grantmaker would. This meant that although we did clarify the groups’ initial plans for utilising the funds, our proposal to the funder, and later our reporting, emphasised the groups’ unrestricted and full governance of the funds, and our minimal intervention in their utilisation. Fortunately, this funder understood the urgency of the situation, the importance of not intervening in the utilisation of these funds after their allocation, and the need to transcend the institutional structures and the humanitarian aid component that dominate what often poses as concrete action.

The two African grassroots MDW groups we raised funds for both shared a goal of supporting their community kitchens: each of them brought together groups of migrants that had been using available spaces to cook meals for the displaced migrants who were shelterless. Beyond the inaccessibility to kitchens and utensils, they had also been funding their work through their own members who had limited to no income to begin with. The meals they had been trying to provide were distributed to the shelterless displaced migrants, most of whom had been discarded or left behind by their employers. We assisted them in surveying their needs, estimating their costs, and determining how funding could be stretched for maximum benefit.

With MDWs having zero access to an already limited banking system, our role was to ensure we disburse the funds to the two groups in cash. Afterwards, the reporting from our side was limited to describing the process. The two groups went on to utilise funds where they saw fit, and to adapt to the needs which had changed with the conditions post-ceasefire. Both groups went on to support their community in ways such as covering travel needs for the return of their members that had been left stranded.

We unfortunately could not engage any other funders in this process as we were hoping to do, which could have been beneficial in supporting other similar communities.

Lessons Learned

We once again understood that there is no plan, no outlook for action during crises; when crises befall us again, and they will, there probably will not be one for the foreseeable future. We are painfully aware of the limitations of our language and our tools when confronting the systems we try to survive every day – systems that are directly complicit in perpetuating the colonial discourse. Our disillusionment with our reality and the erasure of our narratives take us into a darker spiral where we admit to our losses only to prepare for the loss to come.

Over a year later, Lebanon is still being bombed, people remain displaced, many cannot return to their homes, and the state still has not developed any disaster response plans. Gaza’s reality continues to deteriorate under extermination, which makes it clear that the region’s suffering and shared abandonment are interlinked. It is as if the world and (ironically) the leaders of the global south have sold us to the enemy, while the west promises economic prosperity in return for further compromise and disarmament. The United States colludes with Israel to build what Trump is defining as an “economic” buffer zone in the south of Lebanon, promising security and economic prosperity in the form of resorts and corporate entities. Through free market frameworks, colonial powers once again and unsolicitedly offer revolutionising tech through structures like Starlink, all while the local ruling class shamelessly reaps what it’s offered. People meanwhile attempt to move on by retreating into the mundane and by struggling for their survival under capitalism. The future looks bleaker than ever, and as always, the unseen are left behind.

Against this despair, it becomes clearer than ever that words of solidarity alone cannot sustain life. Declarations, campaigns, and statements that circulate but do not mobilise resources remain within the language of symbolic care, while communities continue to face annihilation without material support. The question of funding is therefore central: not funding as defined by donor logics or NGO frameworks, but the circulation of resources that can reach those who need them directly and allow them to act on their own terms. Refusing NGO frameworks means rejecting both their bureaucracy and their obsession with accountability to institutions and imperial states rather than to people. It means acknowledging that effective support cannot be measured in reports or percentages but only in the lives preserved and the communities sustained.

This moment also demands a reckoning with post-war fatigue – a fatigue that numbs people into forgetting, and convinces them that individual survival under capitalism is the only option. This fatigue is precisely what allows the enemy to grow stronger while we retreat into despair. To transcend it, we must build forms of relation and praxis that can outlast the cycles of destruction. Otherwise, our exhaustion will be weaponised against us, and the very possibility of resistance will collapse under the weight of forgetfulness.

Transcending fatigue also requires transcending the limits of traditional fundraising, particularly the dependence on western donors who use resources as colonial tools of silencing and control. This war has revealed again that our survival can neither rely on western funds that evaporate the moment we speak with clarity, nor on NGO structures that fragment our capacities into projects and reports. What we must seek instead are circular forms of resourcing, rooted in our communities and solidarities, that preserve autonomy and allow action in moments of crisis. Such an approach is not yet a system, but its seeds are planted whenever funds bypass bureaucracy and reach the people of the land directly.

What we seek now is not a definitive answer, but a space to dismantle the scaffolding of crises, to unpack the architecture of devastation, its myths, its soft power, and to collectively refuse its inevitability. There is no promise of futurity here, only the insistence that other relations remain possible – through continuous and perpetual education, through conversation that is not extractive but transformative, through forms of support that resist being absorbed into the machinery of humanitarianism. Perhaps what we need now is not a blueprint, but a threshold, a space through which possibilities once deemed unthinkable, obscene, or impossible might enter.

We move toward that threshold not with certainty, but with fragments, refusals, and fugitive forms. We gather what resists cohesion not to repair or complete it, but to let contradiction speak, even in broken or partial language, and to commit to listening together.

- 1. 2800 on September 17 and 608 on September 18. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/09/18/lebanon-exploding-pagers-harmed-hezb... https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/lebanon-establish-international-inv...

- 2. https://www.newarab.com/news/what-israels-arrows-north-operation-lebanon

- 3. https://reliefweb.int/map/lebanon/lebanon-regional-displacement-overview...