The Ghosts That Haunt Us: (Anti)Colonial Residues and Feminist Solidarity in Everyday Archives

In this paper, we undertake an experiment in everyday archiving from our specific locations in the matrix of asymmetrical colonial relationship between India and Kashmir. As feminists invested in making sense of our contextual complexities and building anticolonial solidarities, we look back and document in their rawness: our spatial, temporal and sensorial experiences of 2019 and 2020. These years marked major political escalations in Kashmir and India but also saw radical political formations resisting coloniality within and beyond the nation-state borders. Our collaborative process of assembling everyday archives – banal encounters, personal reflections, conversations, visual and sensory narratives – thus became a feminist meeting place. Built on our respective paranoid stances that identify lack of sustained and solidaristic engagement between Kashmir and India, and variously appear as fear, dejection, indignation, and exhaustion, we find in our archives moments of reparation. These are also moments that delineate our encounters with colonial ghosts, their ever-changing shape, and the haunting they produce; sites we find generative in mapping the connectedness of our struggles and scope for a transformative praxis. Overall, we make a case for sustained engagement with archiving, cross-reading, and co-writing as a means of critical thinking and forging reflexive solidarity.

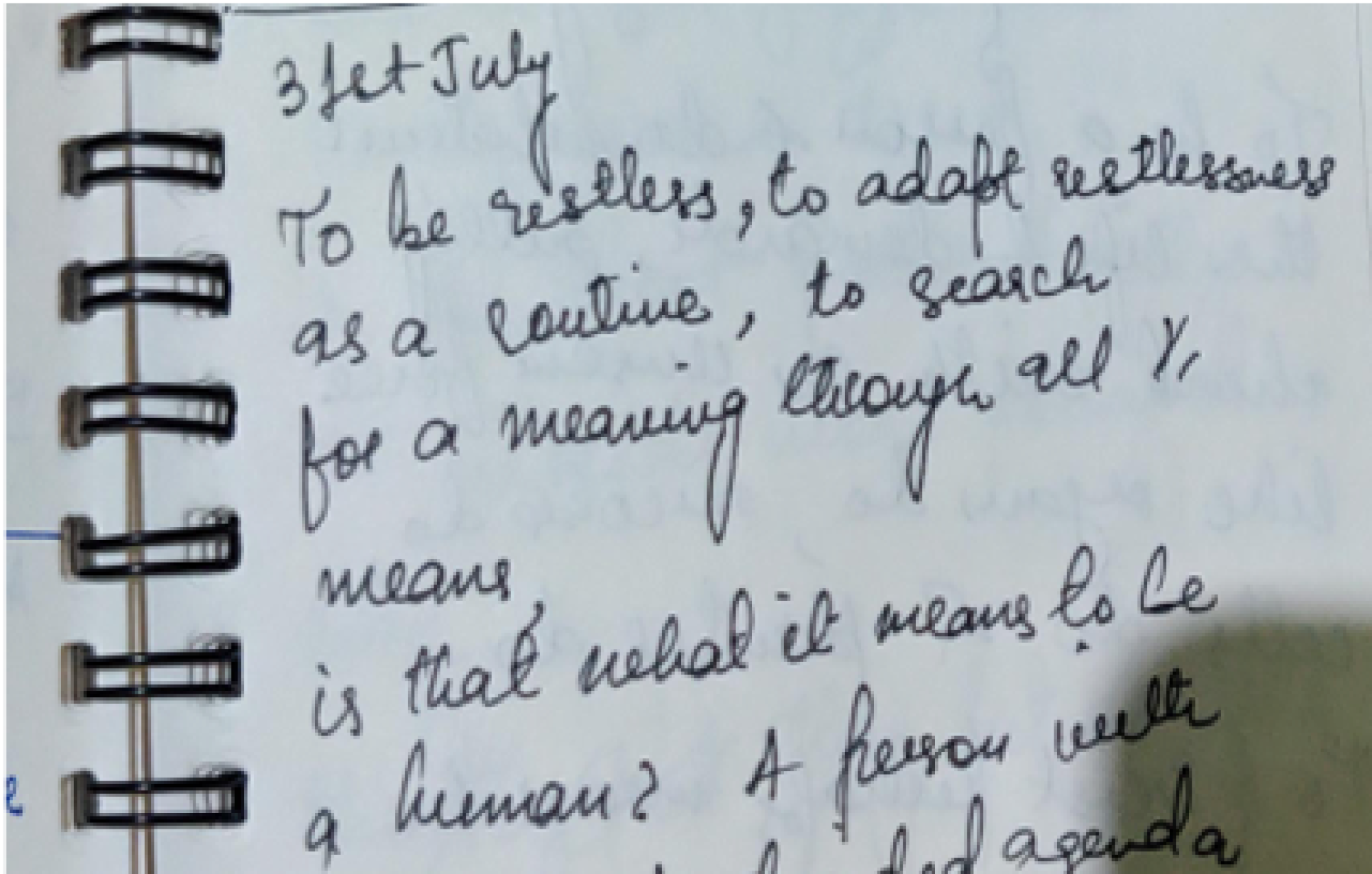

picture111.png

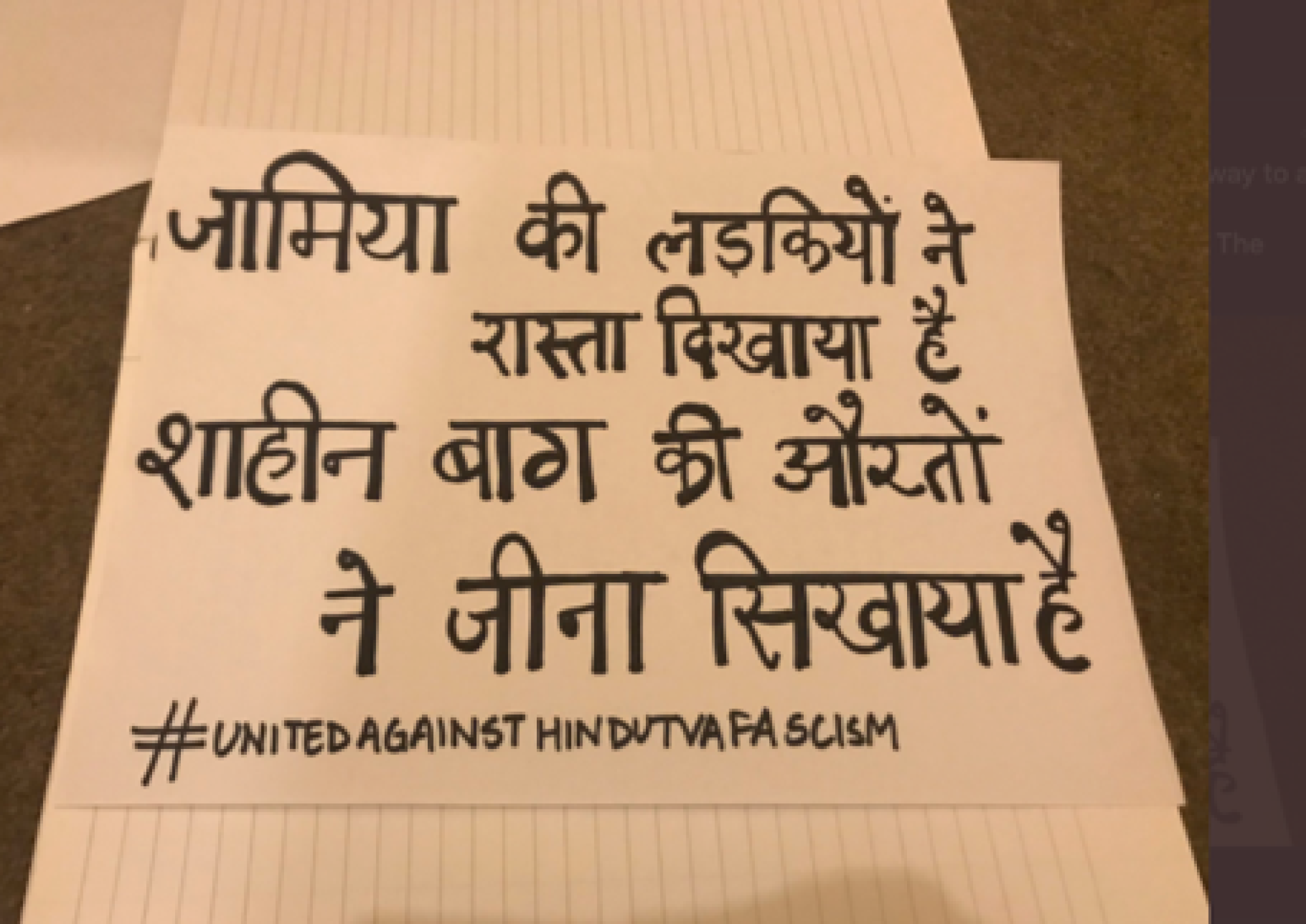

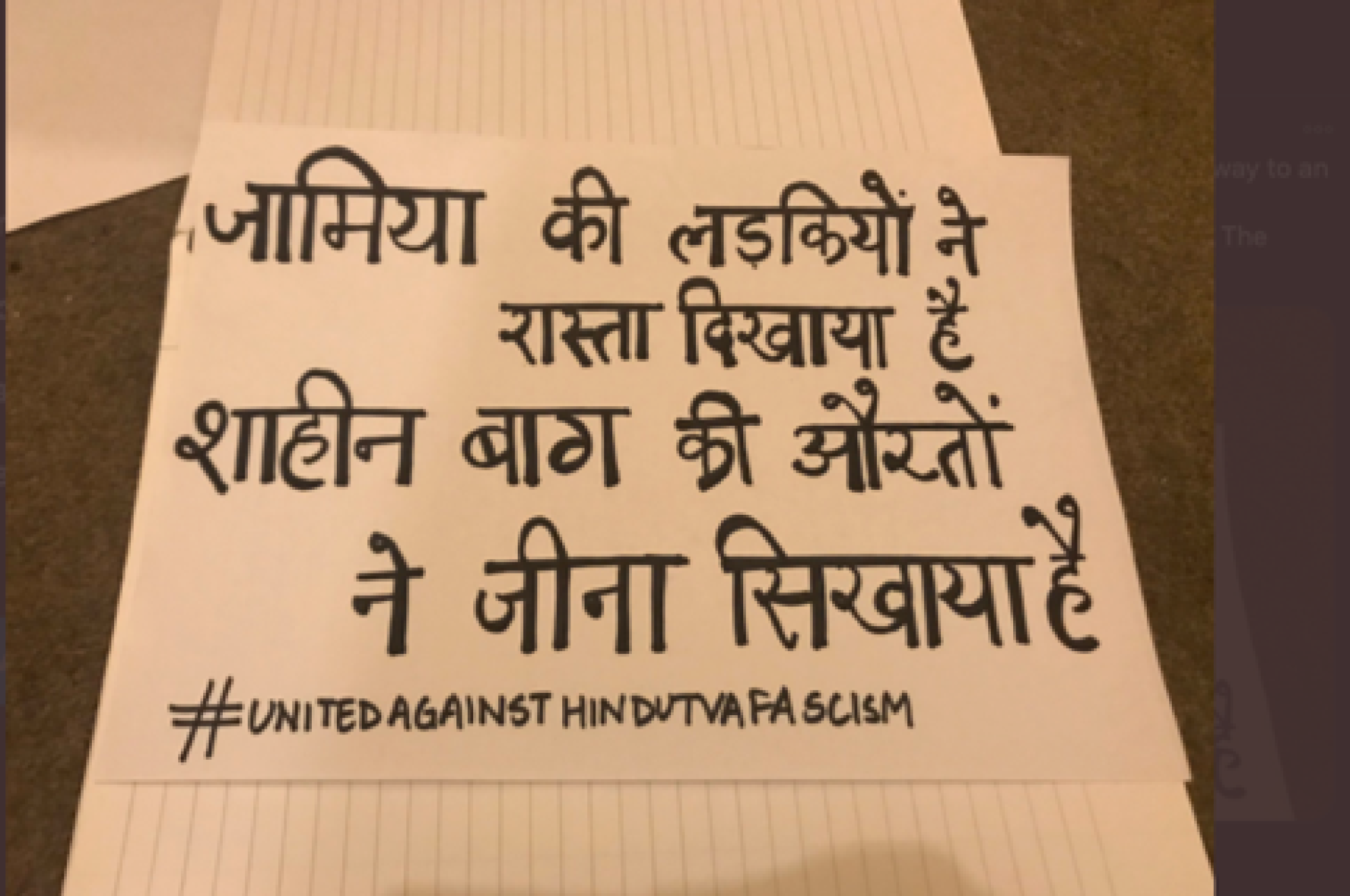

Image 3: A protest poster I created. In English: the girls of Jamia have shown us the way, the women of Shaheen Bagh have taught us how to live.

Waqt chu gawah

Time is witness

-Kashmiri Bella Ciao by Zanaan Wanaan, 2020

“The ghost is not simply a dead or missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to that dense site where history and subjectivity make social life”

-Avery Gordon (2008; 8).

Prelude

To varying socio-political degrees, 2020 symbolised dislocation for most of us. Yet to mark the year as a distinct temporal break because of COVID-19 would be myopic, or at best, a partial retelling that obscures longer histories of violent exclusions and coloniality in recent times. During 1947 Partition when India and Pakistan emerged as nation-states amid religious bloodshed and mass migrations, Kashmir was tyrannically annexed to India, lengthening the region’s centuries old ordeal with yet another occupier (Wani, 2020). Kashmir has not been ruled by Kashmiris in the last 430 years (Halder, 2019). Landlocked between two simmering “postcolonies,” and a fixed object of their political deliberation and desire, Kashmir’s descent into the pandemic co-occurred with its newly carved histories. Six months before the pandemic made it to Kashmir, the Indian government had stripped the region of its territorial sovereignty, passed a variety of disenfranchising laws, and enforced a complete corporeal and communication lockdown. The Kashmir that survived COVID-19 first wave bore the political burden of “law and order:” a colonial manoeuvre that made lockdowns, barricades, searches, and curfews “sacrosanct” to suppress Kashmiri resistance in the name of national security (Shamim, 2020). Further, it bore consequences of Kashmir’s historic claim for self-determination – and the punishment that is inflicted by the colonial state precisely because Kashmiri people harbour such aspirations. The pandemic, therefore, was militarised and received by the political, economic, and affective burden of the 2019 lockdown, and of the seventy-three years that precede it. With only 93 ventilators for a people of millions, “guarded” by 0.7 million Indian soldiers (JKCCS, 2018) and the ghosts of 2019, Kashmir dealt with a complex, violent (Bhat and Mugloo, 2020), and debilitating reality in 2020.

Along with revitalising military subjugation and settler policies in Kashmir, the Indian government, towards the end of 2019, passed the discriminatory Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) that introduces religious identity as a criterion of granting Indian citizenship to undocumented migrants from neighbouring Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. All but Muslim migrants and refugees from these nations were excluded from expedited citizenship, sparking vociferous nationwide and transnational movements against CAA and the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC). The latter places arbitrary demands on existing Indian citizens to prove their citizenship and together, they hold the possibility of disenfranchising millions of Muslims (Rao, 2020). These obvious exclusions alongside systemic anti-Muslim and caste-based oppression in India engendered newer and radical political alliances cutting across class, caste, religion, domicile status, and through their differences. An example of this includes calls for and displays of Dalit-Muslim unity by Bhim Army chief Chandrashekhar Azad (Kabir, 2019). In the following months, Muslim-women led sit-in at Shaheen Bagh in Delhi and student demonstrations sparked similar movements with thousands of protestors across India. However, fascist insinuations from ruling party leaders led to an anti-Muslim pogrom in the capital city of Delhi killing 53 people (The Wire, 2020).

Our locational and politically situated experiences as a Kashmiri Muslim woman (Samia) and caste-privileged Indian woman from central India (Niharika) tether us to a complex matrix of asymmetrical colonial relations between Kashmir and its military subjugation. More specifically, we experience the consequences of our histories and socio-political realities at different locations: one who is part of (by the logic of birth, citizenship status) the colonising nation-state, the other who is colonised by the colonising power (racialised as Kashmiri Muslim and forcefully integrated with the nation-state). As such, we experience these realities at varying tenors: visible consequences due to structural placement of our bodies earmarked for assortment by the colonising nation-state that devises its violent logics on us, albeit differently; and the invisible consequences: intangible, intimate, affective, and possibly inarticulable. Yet, it is through these differences that we want to understand what it might mean to archive our disparate struggles – that remain connected in their genesis – in their granularities, messiness, and colonial presents that appear in and variously shape our everydays. We begin by taking our differences as a starting point to trace back their genesis; look for connections, colonial residues, our “shared” and “distinct” affective responses to them.

We continue to grapple with defining our shared and distinct realities and how they carve our respective identities. Even in their fluidity, we understand these identities as always entangled with power asymmetries, the overarching colonial history of the Indian subcontinent, together with historical intimacy in our cultural and linguistic communions (Asif, 2020). Altogether, these complexities evade neat categorical capture. Amid these (post)colonial uncertainties and (volatile) intimacies, what routes does everyday archiving open up? What are its implications for feminist (desire as well as necessity of) border-crossing (Anzaldúa, 1999) and building solidarities specific to our context? Or as Mehta (2020) asks: “How do we realise solidarities through the political work of dreaming, imagining, creating, and nurturing while holding each other? How do we imagine new and never-before ways of holding each other?”

On archiving and how it emerged as a method of documenting evidence

The events that took place in India and Kashmir during and after 2019 are not isolated from the colonial realities and historic exclusions that have been perpetuated on its peoples. However, because of our positionalities – the immediacy of these exclusions and the response they demanded – these events also exerted discernible influence on our bodies and lives. They shaped the ways in which we understand coloniality of the Indian state and our responses to it. As our archives reflect, these influences manifested in our lives affectively and physically. With that, they also created space for moments of solidarity, determining the texture of our responses: choices, behaviours and political aspirations; desires, hopes and longings that followed. We understand these moments as those we collectively, and personally, cannot depart from, just as these events cannot be isolated from the histories of their making. However, there were/are openings for different forms of (feminist) responses.

In many ways, the substance of our method is derived from the influence these events had on us, our friends, families and communities through witnessing forms of collective/personal resistance: The protest led by women in Shaheen Bagh inspired formations in India and beyond. The knowledge produced and disseminated during the protest, the growing community of activists, as well as the use of public media platforms as protest tools deeply informed our practice. In this time, archiving emerged as an all-pervading response at multiple protest sites and across mediums. Examples include Fatima Sheikh-Savitri Bai Phule library at Shaheen Bagh, Shaheed Bhagat Singh library at Dakha Singhu border, the principal site of farmers’ protest, proliferation of critical reading groups, university teach-ins, and public lecture series. Correspondingly in Kashmir, after internet services were curtailed in August 2019, large public demonstrations were organised by Kashmiris across the world with thousands in solidarity. Kashmiris residing outside of Kashmir set up social media solidarity communities; working groups for activists, lawyers, and students to file petitions, support the Kashmiri community, and produce knowledge on Kashmir’s long colonial history and state violence. Information was disseminated through talks, webinars, sit-ins, campaigns, protests, and marches. Social media communities and platforms such as Stand With Kashmir, With Kashmir, Zanaan Wanaan, Kashmir Solidarity Group, and Kashmir Reading Room played a pivotal role in forging transnational solidarity for Kashmiris.

As young feminists who share colonial histories and their ghostly encounters, we see these radical political formations and their insistence on reading, writing, archiving, and collective study as means for critical thinking and knowledge production. They allow us to (re)imagine what molecular solidarities and border-crossing across identities, anti-capitalist, anticolonial feminist orientations can look like. It is worth noting that even though we draw inspiration from them, our archives are not one-off reflections, but developed over the course of these years and are attached to immediate events/responses and the ones that preceded and followed them. We offer these archives in their rawness and look for scope therein for solidaristic ways of being. While integral to our process, this paper is not its end goal or that of the purpose of archiving. What we show is a temporal fragment of the archives to make a case for a sustained practice of archiving, cross-reading, and co-writing as part of our feminist politics that offers no guarantees but is carried forward by collective journeys (Nagar, 2019). For us then, this practice continues beyond this paper, beyond the specific events presented here or how they continue to haunt us.

Everyday Archiving: an experiment

2019

S: Over the course of my life, I told myself the story that “making pain a powerful tool” for “bringing justice” could be my way of “contributing” to the world. I was attached to such endeavours perhaps because these were the only consolation to my immediate condition, they offered logic to my circumstances with convincing evidence. As a young girl, I thought I’d become the Kashmiri evidence of “triumph of good over evil.”

Many children in Kashmir believe in such revolutions and grow up to realise such ambitions take more than self-dedication, that human bodies are fragile, and pain can transform into “power.” In this context, 2019 was not the worst thing that happened to Kashmir, as many experts argue, but it was definitely the worst many Kashmiris have witnessed so far in their lifetimes. In fact, it offered evidence of how easy it is for people’s worlds to shatter. I once had one conversation with a self-proclaimed patriot who asked me why “Kashmiris are terrorists.” I did not respond to her questions: “What do you mean you will win eventually? Civilisations have been razed and made to disappear with power? Where are those people now? They are all dead and so are their inqilabs. ‘Might is right. Jitna jaldi seekhoge utna acha hai tumhare liye’.”

After August 5, like many Kashmiri friends, I spent four months in a single room, suffused in the terror that had fallen over my home, Kashmir – terror that was material too. It found its way to my journals and writing, it distanced “close Indian friends,” altered career paths, and made me less of a traveller than I thought I was. I carried Kashmir everywhere. In September 2019, on my birthday, my friends arranged a party to cheer me up. In situations like these, it is difficult to explain to people that there is no space for the idea of cheering up. A birthday celebration is a luxury out of bounds; we never have them even during “stable” times. I sympathise with people in Kashmir who have never been in a position to make do with small joys. On social media, the exercise of telling people “the truth of Kashmir” seemed so trite and useless. Often our miseries are needlessly put on display. If people could truly empathise, they would have spoken up. Understanding oppression/suffering is not rocket science. Thinking of Indian friends who departed from these conversations still leaves a bitter taste in my mouth.

After four months, in January, I decided to drift away. I could not save Kashmir, at least not immediately and with my health in shambles, with nothing but a reservoir of anger that I could not manage, so I decided to do 2020 differently.

picture1.png

Image 1: A picture I sent to a friend (to show her how exhausted I was) in September 2019, after spending a month reading news, updates on Kashmir on social media & making many attempts to contact loved ones in Kashmir

picture11.png

Image 2: Entry to Srinagar’s Zero Bridge, empty and barricaded, October 2019

N: 2019 was about shock and spatial re-imaginings.

In April, my father in his early fifties died of a cardiac arrest. It was both dreadful – for the death of a parent was beyond anything I had imagined would happen in the four years of my PhD – and shattering because a lot remains unresolved; trauma and pain unspoken and now cradled as unrequited guilt in my body. They often come back to haunt me in my nightmares. Why I recount this is because his death catapulted my ongoing engagement with the spaces we cohabit – how some spaces that we are told must be familiar remain alien, alienating and violent throughout, only for an event to upend it all. And the affective labour, care, and exhaustion that goes into rebuilding these spaces with revolutionary reckonings. Revolutionary precisely as it was disallowed. Revolutionary because survival would be impossible otherwise.

It was on August 5 that India put Kashmir under yet another siege, which many Kashmiris understood as the complete annexation of their homeland by the Indian state that began in 1947. August 1947 was when India became free/Azad/Swadheen from British colonisation. It is indeed sobering for those of us with caste privilege to keep reminding ourselves that the birth of “our” nation has always been entangled with political dishonesty, unkept promises, and dead bodies of the inhabitants of this land. This uncut umbilical cord of coloniality has now poisoned the entire “postcolony” with Hindu supremacy, anti-Muslim, caste-based violence, and a deep hate towards women, sexual, and gender minorities. The ghosts have come back to haunt us; perhaps they never left us. But their presence is no longer spectral. In the case of the Kashmir siege, I saw them taking shape as lack of consent and colonial violence. And all of these interpellated as the masculinist militarised Hindutva state that is now India. This came as a spatial, sensorial shock. Unsurprising but a shock, nevertheless.

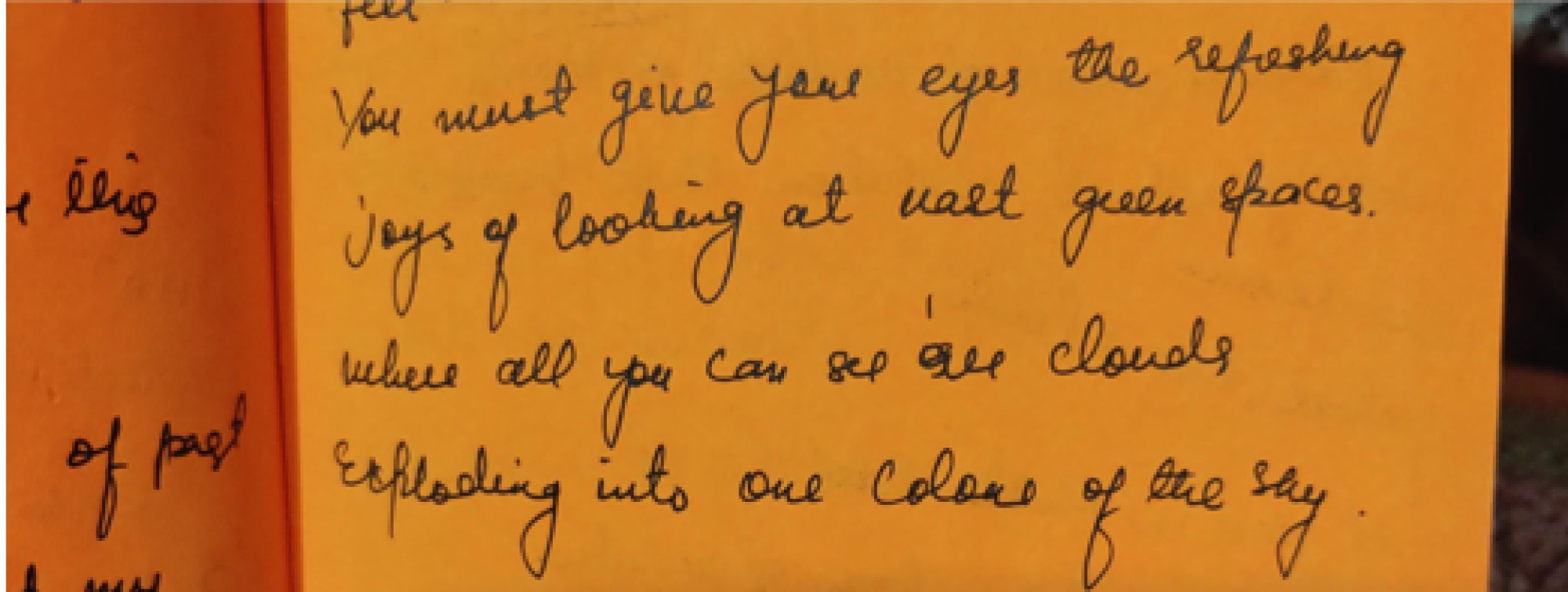

In the months that followed, Kashmir was silent. Some Kashmiris living outside of Kashmir were painstakingly historicising India’s military occupation and the illegality of this latest siege. Indians were mostly silent too, but ours was a silence of privilege and of liberal facades. Free Kashmir, but only of the communication lockdown. Kashmir is caged, but only by the current far-right government. These caveats were symptomatic of the historical denial of India’s coloniality in Kashmir. For most Indians, Kashmiri Muslims are “terrorists” after all and so, expendable. Some of us here in London participated in solidarity demonstrations. The numbers slightly increased with the passing of discriminatory citizenship laws in India. After all, the shock now was closer to home, more immediate and threatening.

picture111.png

Image 3: A protest poster I created. In English: the girls of Jamia have shown us the way, the women of Shaheen Bagh have taught us how to live.

December was about protests. It was also a month of violence. We witnessed Muslim-women led Shaheen Bagh sit-in, student-led demonstrations notably in Jamia Millia Islamia university, subsequent police violence, and anti-Muslim pogrom in Delhi. Never in my living memory had India emerged into such nationwide protests. All was not over yet, it seemed. My days and nights were a mix of crippling anxiety, information sharing, university teach-ins and discussions, protest material creation, and conversations with “apolitical” acquaintances and concerned others about India.

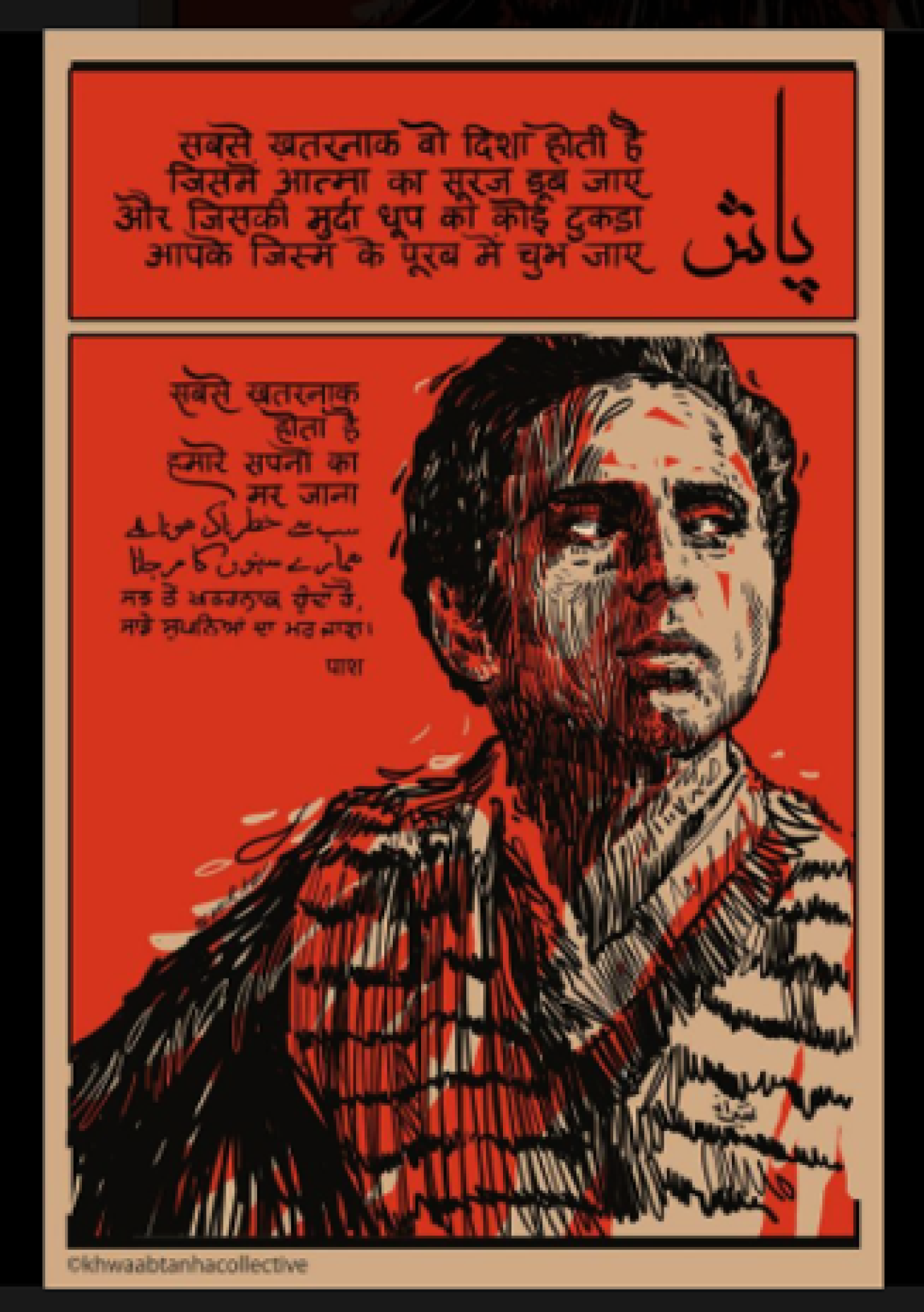

Fascism does not simply eat up the body or remake space. It also pries on our time; it slows, delays, freezes time and being, making us feel that there is no difference, that we are headed towards doom. That nothing is happening, and no one is listening (and often nobody does). It thrives on defeatism. It is parasitic. So, in a small act of spatial remaking, my home had revolutionary poetry by Pash, protest posters and postcards that proclaimed: resist, educate, agitate, organise. My home now had inquilaab (at least spatially) written on its walls. All is not over. Not yet at least. But what next?

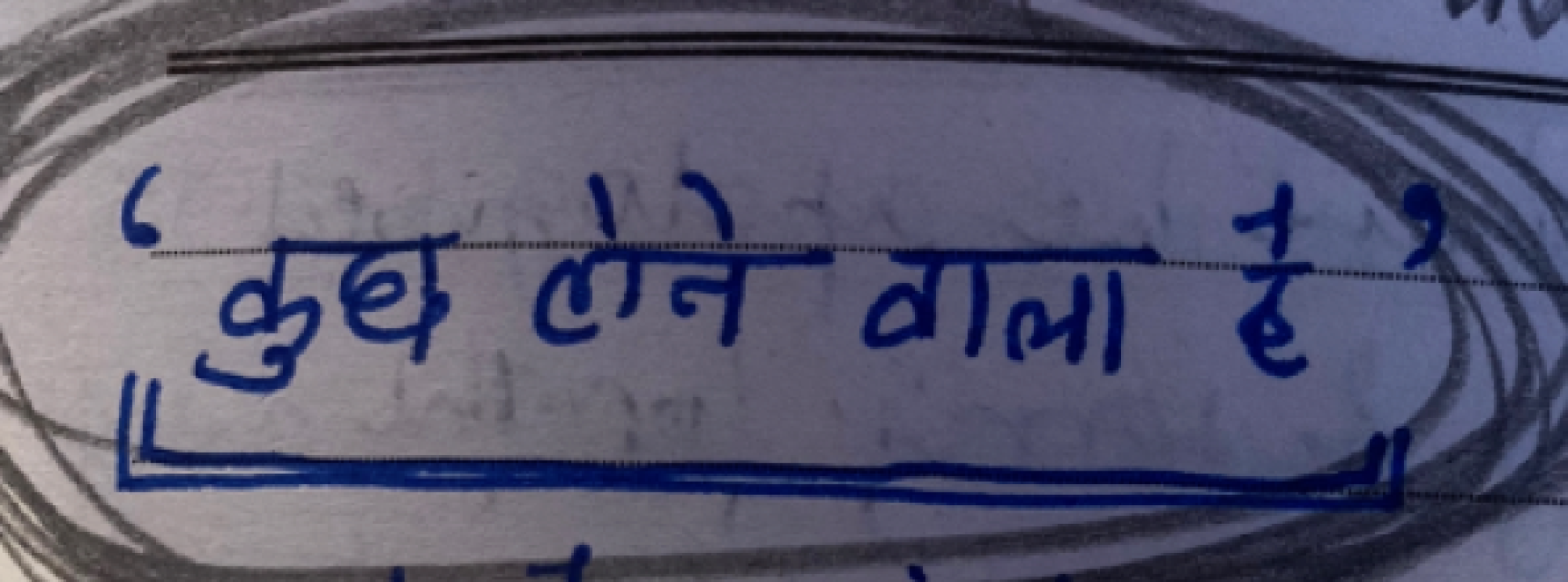

picture21.png

Image 4: Poster of Pash’s revolutionary poem “Sabse Khatarnak Hota hai” by Khwabtanha collective, in my home.

January – February 2020

S: I left Kashmir and Delhi because all these cities reminded me of how sharply my life is contoured by my identity. I attempt to leave cities every once in a while, and I have come to realise it is my body in defense. I let my body do this, because this is the farthest I can go from reality: in denial. In January, I moved to a new Indian city for work; far south not a lot of hoarding boasted of the true Bharati Prime Minister. Muslims seem comfortable. They shop at all places, visit cafes, are present in offices, and have many Hindu friends. They excuse themselves for namaz and nobody winces. Women in abaya are friends with women in trousers. In private, I ask a Muslim colleague to confirm my observations; they say, “On surface, everything looks peaceful, but the saffron colour is brewing. Like it was brewing many years ago in Delhi and Uttar Pradesh. You never know when things will change.” I refuse to see it; I must pretend, for the health of my heart, that I am safe. I enjoy spending time with this one woman. She is passionate about welfare initiatives in her state and is well versed with the problems on ground. We spend hours together each day, but she never enquires about Kashmir. She knows I am not a Hindu. One day she tells me her state needs a supreme, selfless leader, with the sanctity of a true Hindu. “Our city too will change soon,” she smiles.

At night I read the poetry I had penned down in Kashmir, clumsily written, but an easy way to teleport to home. I close my eyes and see the walnut tree shshshshsing in the wind, some nights I hear bullets, I have nightmares. Good or bad, at night I am always in Kashmir.

picture13.png

Image 5: Babasaheb Ambedkar greeting pedestrians leaving the government building in an Indian city.

March 2020

S: I remember Arundhati Roy articulating in her debut book, The God of Small Things, that it is easier to point out and to talk about big tragedies because the small things in life are almost out of reach and somehow painful. But even small things can loom large and can change the total course of life.

My mother lost her father to an improper surgical procedure when she was an infant. Her father’s death altered the lives of my mother and her sisters. They lived in poverty and borrowed money to complete their education; trauma shapes all aspects of their lives. My father lost his mother on a snowy night to a mistreated tumour. They drove her dead body 50 kilometres from Srinagar to Sopore, using spades to clear out the snow every two minutes of the drive. Along with the weight and consequences of occupier’s colonial ambitions, all Kashmiri stories have poverty, weak healthcare, and a debilitated education system play a part in making them tragic. “Conflict” and “quality of life” are not mutually exclusive, but on days when self-determination seems a long-lost dream, “quality of life” seems almost pursuable. I pursued “social development” because I did not want another young child in Kashmir to lose a parent. You cannot tell a child they must wait for Kashmir to be conflict-free for their parents to live. How long will Kashmiris stay in the dark? The generation that graduates from schools next year, will have spent only a few years in school in their entire lives. This is a loss that cannot be compensated. From the outside, people see macro visuals of life in Kashmir: curfews, death, blood, slogans, and stones. They do not see how every life is affected in the most painful ways, in small and big estimates. They do not see the micro, the intimate tragedies, the blood being washed off. They do not see our struggles to sleep at night; they do not see Kashmiris going from intelligent young people to losing any motivation to live. They do not see generations living this collective reality. What they also do not see is how Kashmiris lack access to basic healthcare, education and life due to the war.

“Trauma in person, decontextualised over time, looks like personality. Trauma in family, decontextualised over time, looks like family trait. Trauma in people, decontextualised over time, looks like culture.” (Menakem, 2017)

The first thing I do after the pandemic is announced: I try to understand how bleak the chances of Kashmir are. Less than 100 ventilators for a population of millions under the watch of the omnipresent Indian guns. In a foreign city, I work on maternal and child health. For five days a week, 8 hours each day, I rack my brain to help better people’s lives. Yet, I cannot weigh Kashmir on the same scale because Kashmiris are politically and institutionally unequal; the evidence is plenty and easy to read. My home is in the hands of a cruel state, in the middle of a pandemic and I have the will, the skills, but no power to do anything about it. I weep over my decisions at night. What could I have not done had Kashmir been with Kashmiris? I think and seek refuge in stories of other Kashmiris who keep trying. Despite having tried converting my “pain to power,” I can only pray for Kashmir.

N: I travel to India for my doctoral fieldwork. The COVID-19 surge in India seemed controlled when I boarded the plane. But only a few days after I reunite with my mother who lives in Madhya Pradesh, a series of strict lockdowns are imposed. News is full of images of migrant workers hoping to get to their villages, and police mercilessly beating up lockdown “breakers” and infantilising men – usually lower caste and class by punishing them into doing sit-ups. I hear middle-class neighbours sharing a laugh about it from their balconies: “What else will the police do? They deserve it!” I have often wondered under what conditions of existence does violence come so easily to a nation.

A few days later, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi asks Indians to bang pots and pans in a show of gratitude to essential workers. Enthusiasm knows no bounds as people show up on their balconies and terraces with pots and pans to beat and conches to blow. Everyone is competing for the loudest noise as a measure of obeisance. In India, politics goes hand in hand with uncritical reverence and god complex. My brother and I are on our balcony looking at some neighbours who are banging their utensils very intensely. My mother laughs and interjects, “I guess this is the effect of WhatsApp forwards saying that vibrations of the conches and prayer bells are effective in shooing away the coronavirus.” All three of us have a loud laugh. Some minutes later, my brother brings his guitar to the balcony to accompany Bella Ciao, the Italian anti-fascist song that I am playing aloud on my phone. An hour later, I am scrolling through Twitter and a Kashmiri journalist and friend has uploaded a video of silent Srinagar. No pots and pans shenanigans. Indeed, a referendum. I laugh to myself.

These theatrics happen as migrants walk hundreds of kilometres, some barefoot and others without food, water, and rest to their native places. Many die of exhaustion and hunger en route. Meanwhile, social media is full of urban middle-class people complaining about lockdowns and having to do all the housework. There is pin drop silence on Kashmir which is under a Russian doll sort of militarised lockdown within a militarised lockdown within a militarised lockdown.

April – May – June 2020

S: In February 2020, I visit an ancient Hindu temple town with a bunch of friends. At each stop, each temple, each statue, there is a mention of the “aggressive and savage” Muslim Sultanates who plundered the rich Hindu land. It is hot and suffocating and I feel I am watched. We left for the town as friends; yet in the town we were Muslims and Hindus. At one point a group of NRIs (Non Resident Indians) guffaw at their guide’s comment: “This is what they did to us but now the tables have turned, ab ulta ho raha hai, Jai Shri Ram.” I keep looking at myself wondering whether I look like a Muslim and what would happen if they know of my political leaning.

In the pandemic, stuck at the apartment, I can no longer run away from my identity. Surrounded by four walls full of posters of Kashmir, a rack full of books on Kashmir, a head full of worry, I have no means to escape. Among friends, sympathies are sent for the Union government and their utmost efforts to save India from the pandemic. I am asked what my opinions are about the Jamatis in Nizamuddin who “led the pandemic in India.” I have to be gentle and remind myself how razor sharp my anger can get. 2020 has to be different. In my room, I seethe in pain, break down in despair, and collect evidence on how those “spitting, spreading the virus, corona jihad” videos are fake. In front of the people who needed to see the evidence, I shiver. Worry about migrant data is heavier than the worry about migrants. GDP matters more than lives that drive that GDP. Rich are obedient, they stay indoors; poor are ignorant, they loiter for food in a pandemic. “What can the PM do? It is unprecedented, it is a pandemic. Look what is happening in Italy.”

In the Muslim majority colony that I live in, the clapping and beating of utensils is another reality check. It rings in my ears like an alarm. The Naya Bharat is nearer than I think. It now has blaring music to it. I keep reminding myself that I must not correlate the utensil beating with the vulnerability of my community in this country. What is my community anyway? Muslims? Kashmiri Muslims? Kashmiri Muslim Women? Kashmiri Muslim Women Feminists? Kashmiri Muslim-born Runaway Feminist Women in Public Policy who are stuck in India in a pandemic in an “Indian Muslim utensil-beating colony” who wants to improve healthcare in Kashmir but also wants to fight against its political subjugation? How did a right-wing government (country?) manage to hurt all parts of us, all parts of me? What kind of consultants, behavioural scientists do they have on board? How do they know the affairs of my heart far better than Allah claimed to? I must resist the hurt; this is exactly what they want.

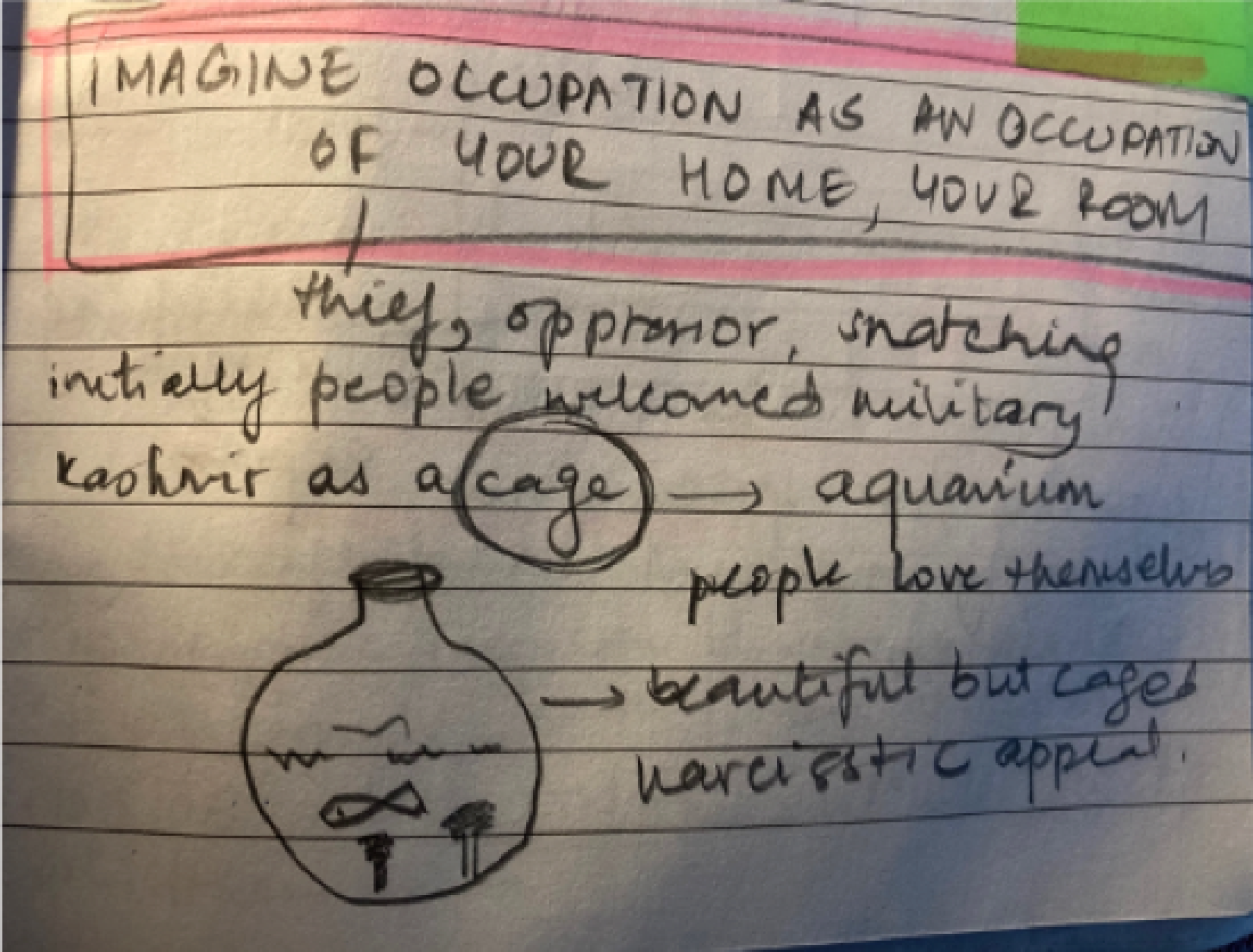

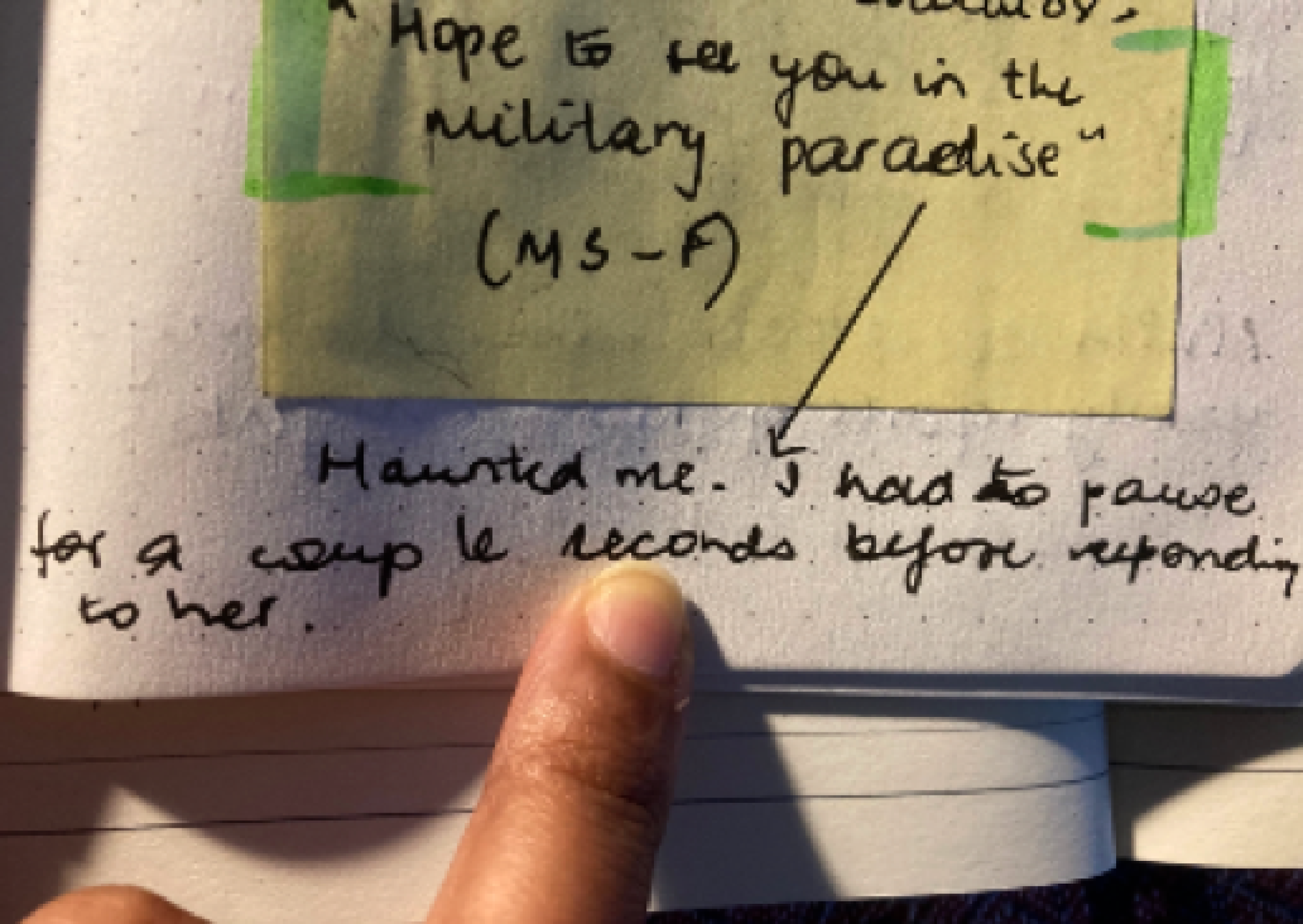

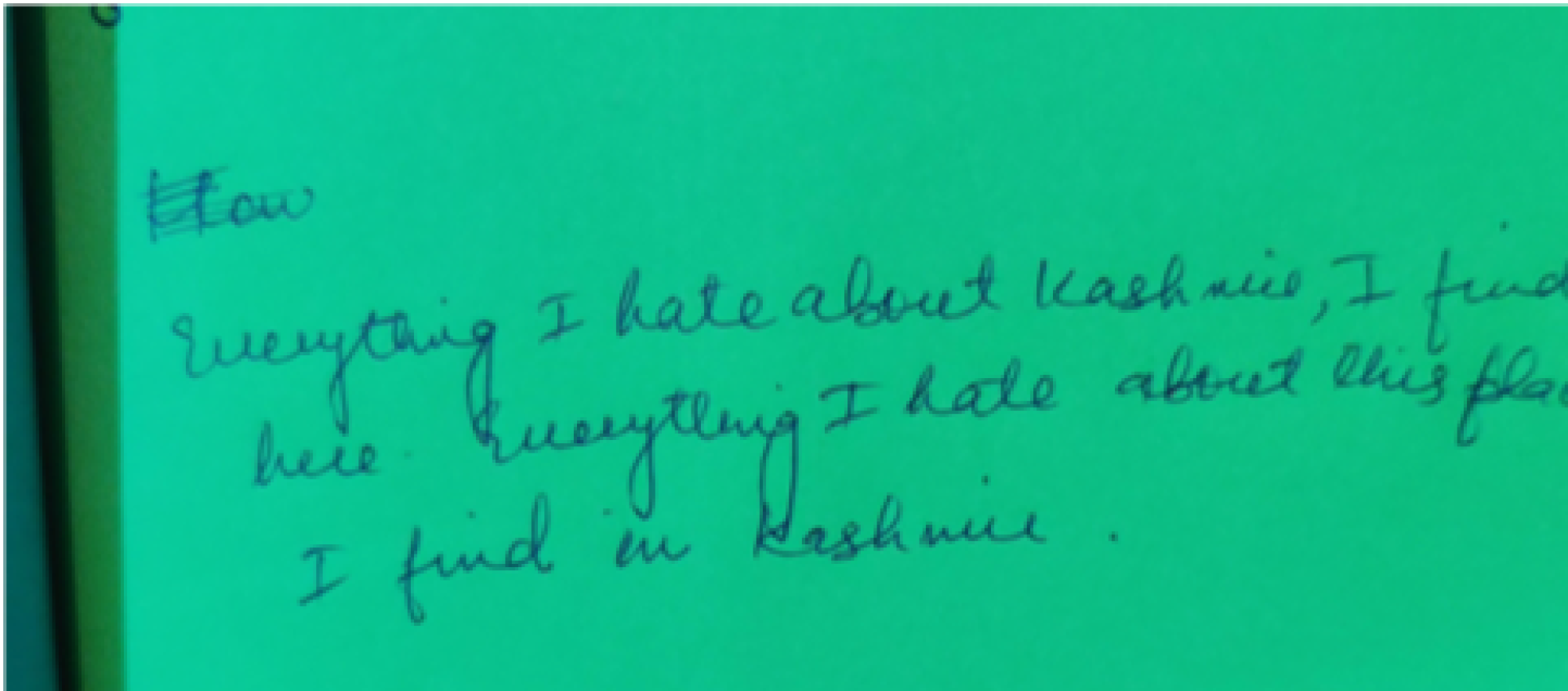

N: I was scheduled to travel to Kashmir for research at the end of March. However, a series of lockdowns, suspension of travel, and closing of state borders have altered all timelines. Nonetheless, I have begun connecting with friends and acquaintances and many have generously agreed to speak to me despite the uncertainties. These summer months were spent speaking with them at length, documenting all that is happening there, and archiving sensorial experiences and feelings. Some snippets from my field diaries and observations made during interviews that convey the viscerality of a colonial occupation:

July – August – September 2020

S: In Delhi once, a doctor refused to treat my severely ill brother after he got to know we are Kashmiris. Mother worried endlessly: “In that city, in a pandemic, who will treat you if you contract the virus?” I agreed; even when this city had better healthcare than Kashmir, it is less likely that I will die in a militarised pandemic in Kashmir, my home, and more likely in our oppressor’s progressive city. The city is not progressive for me; it is progressive for its citizens. As for me, I carry Kashmir’s oppression with me. Moving back to home, then, became a cautious decision.

At home, mom showers me with pink roses. We are teary eyed, but we cannot hug one another yet. Time seems to slip, and I am desperate to save what I can. I record Kashmir like the whole place is a fleeting moment. I explain why I do this to whoever asks but I fail to articulate my desperation. Kashmir is changing fast, becoming something else, losing its land and its people. I must collect whatever remains before it disappears as well. I make an herbarium of leaves and flowers of all kinds. I record sounds of pebbles, rain, and rushing Jhelum. I record my parents speaking about their best memories and their worst fears. I record the cows of Kashmir, the solitary vendor who shouts out in the morning, the herds of sheep that pass silently at night. What I do not cover on purpose are the sounds of firing at night. They are going to stay. On the first night home, I was told the firings are much more common now, especially at night and they are done perhaps to “maintain the fear:” “yem chi khoof thawan barkaraar.”

The pandemic becomes yet another backdrop to our lives, until it comes to front and wreaks havoc, then recedes to the backdrop and returns. How odd living and dying is in Kashmir, how superficial and ordinary.

October 2020

S: My mother has a sharp pain in her abdomen; the test shows an abnormal mass on one of her ovaries. The doctors are hesitant to give answers and keep referring her to senior doctors. Senior doctors prescribe urgent surgery. In the months before October, what we cared most about at home was to ensure elders have minimum exposure to the world outside. Now we had to get multiple tests and the surgery done, and wait for the biopsy results to be normal in the middle of a pandemic. My mother’s surgery brought my attention to two things: how poorly equipped Kashmir’s healthcare system is (what could we have done had Kashmir’s health affairs been in Kashmiri’s hands) and how intimacy-indignation in families co-exist. I love my mother; I am helpless to see her in such otherworldly pain, muttering subconsciously. I realise she misses her family, her youth, and her freedom. But sometimes she can be tough on me. I convince myself it is not her, but her conditions, her childhood, Kashmir, the conflict, having to live up to the role of a mother, wife, sister, teacher. Her tragedies make her bitter, like mine make me angry.

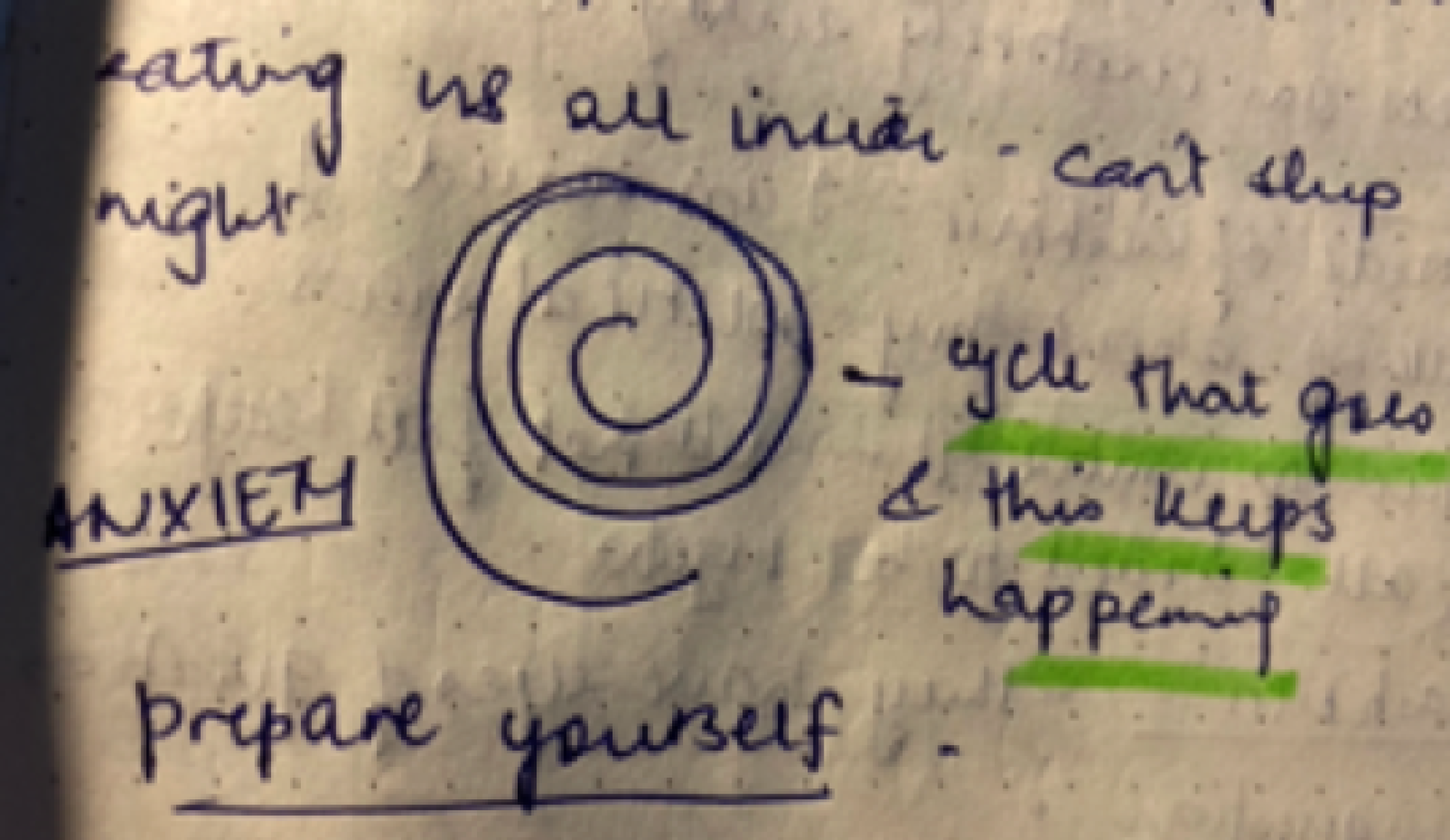

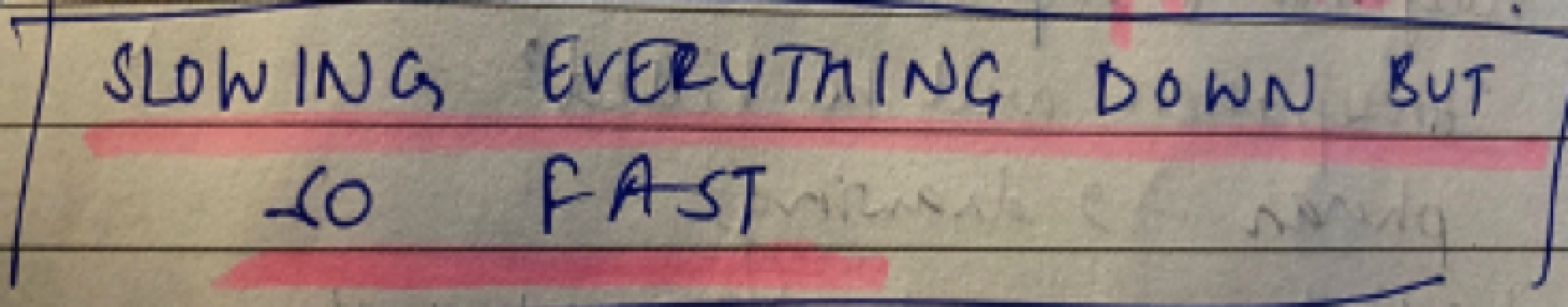

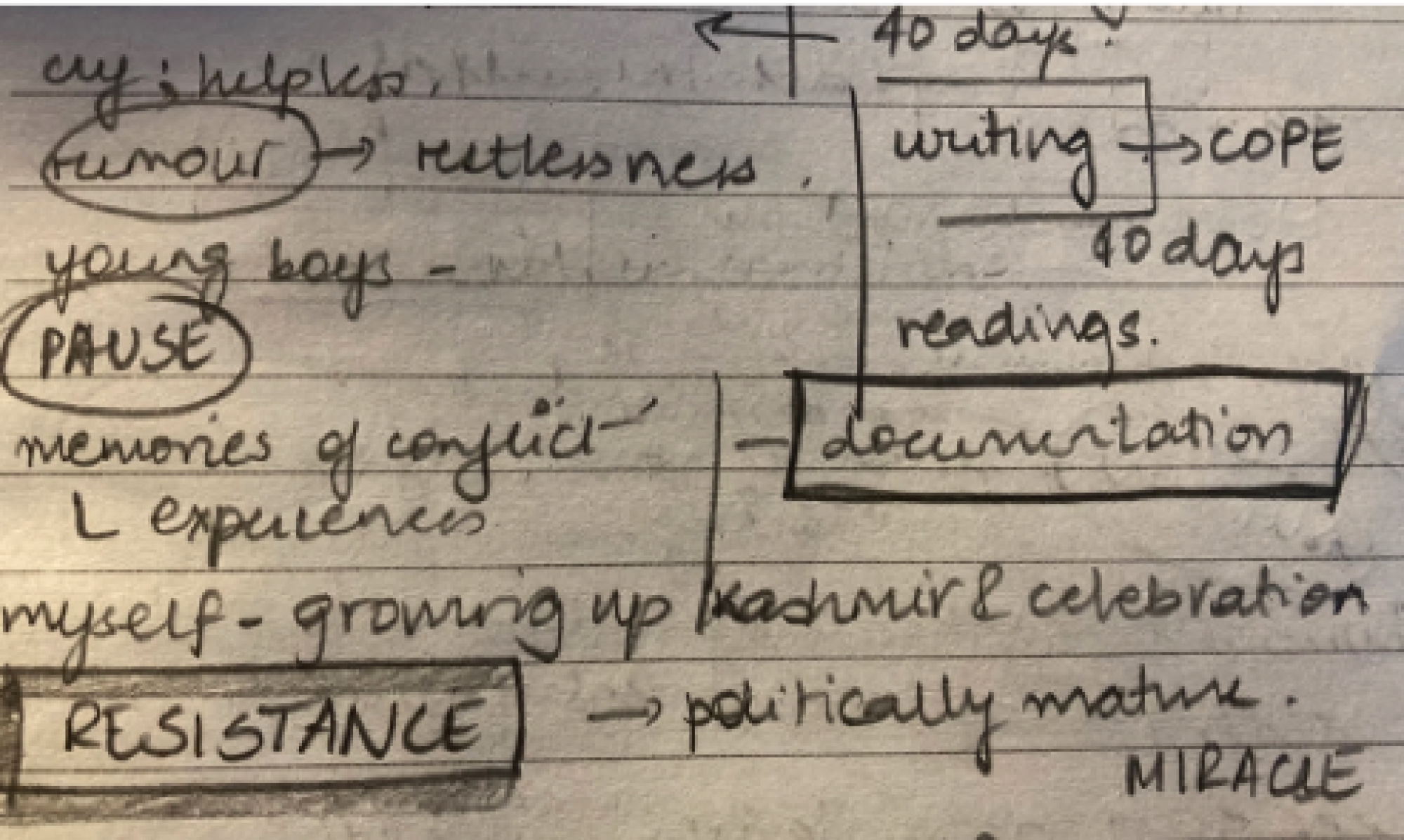

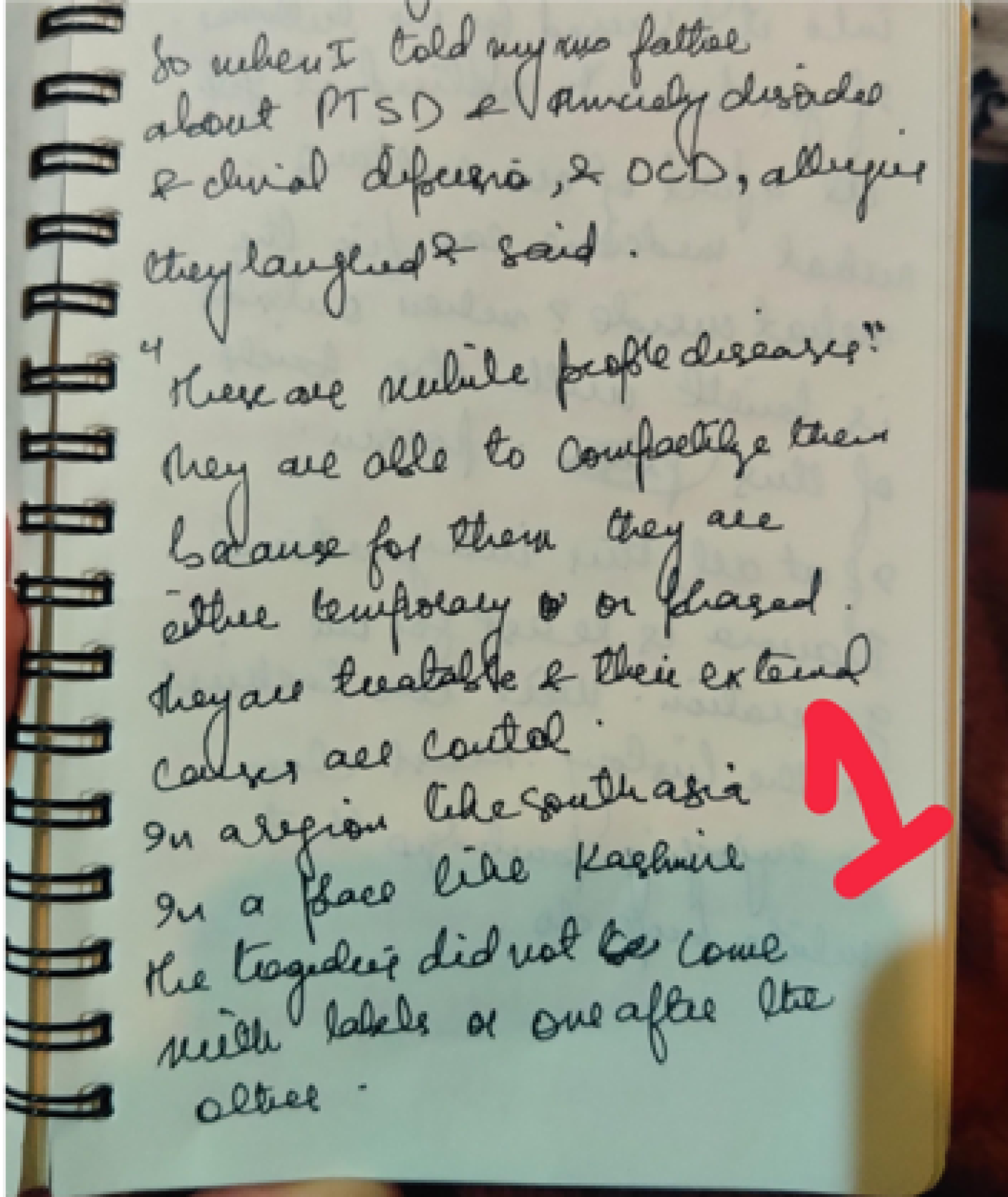

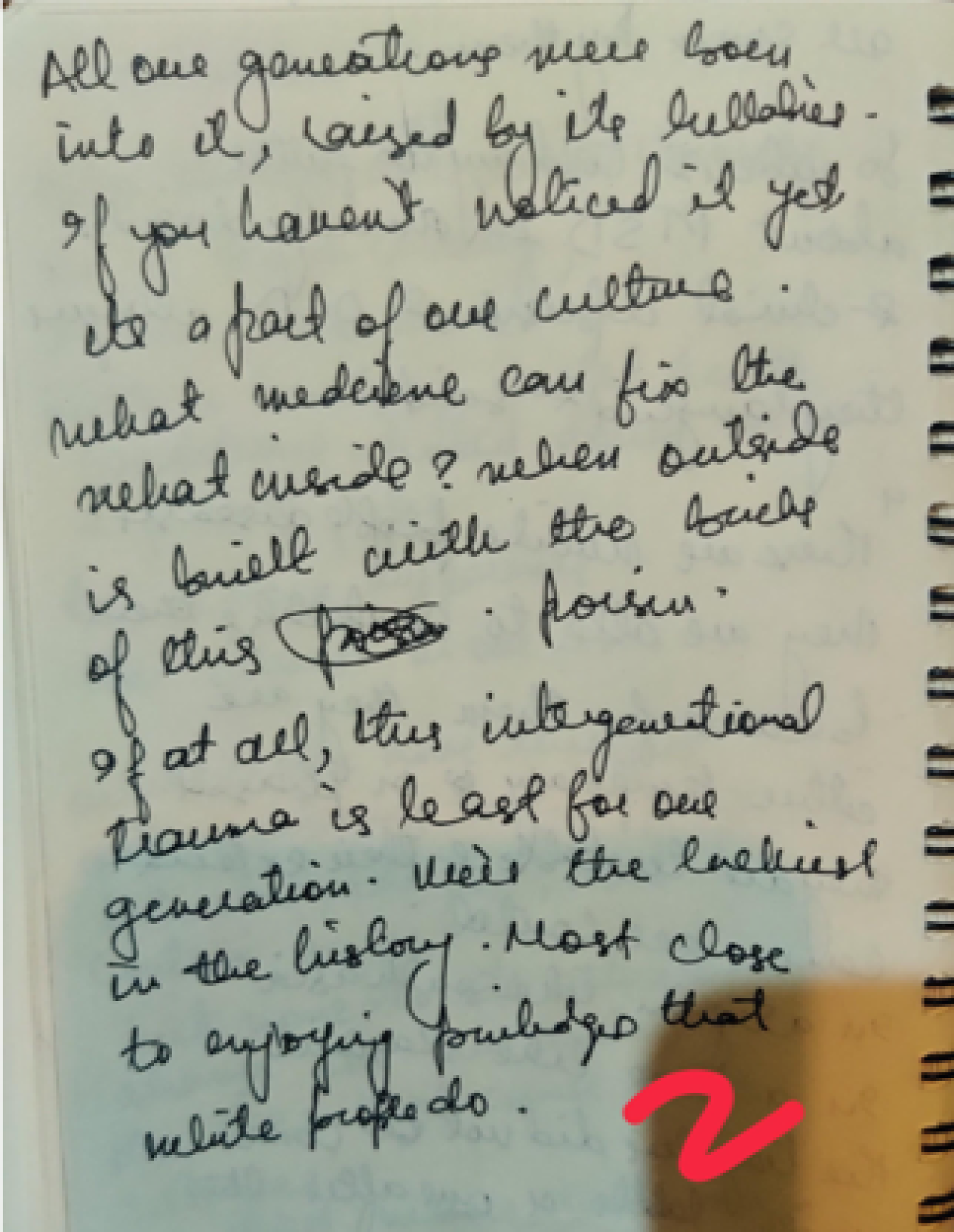

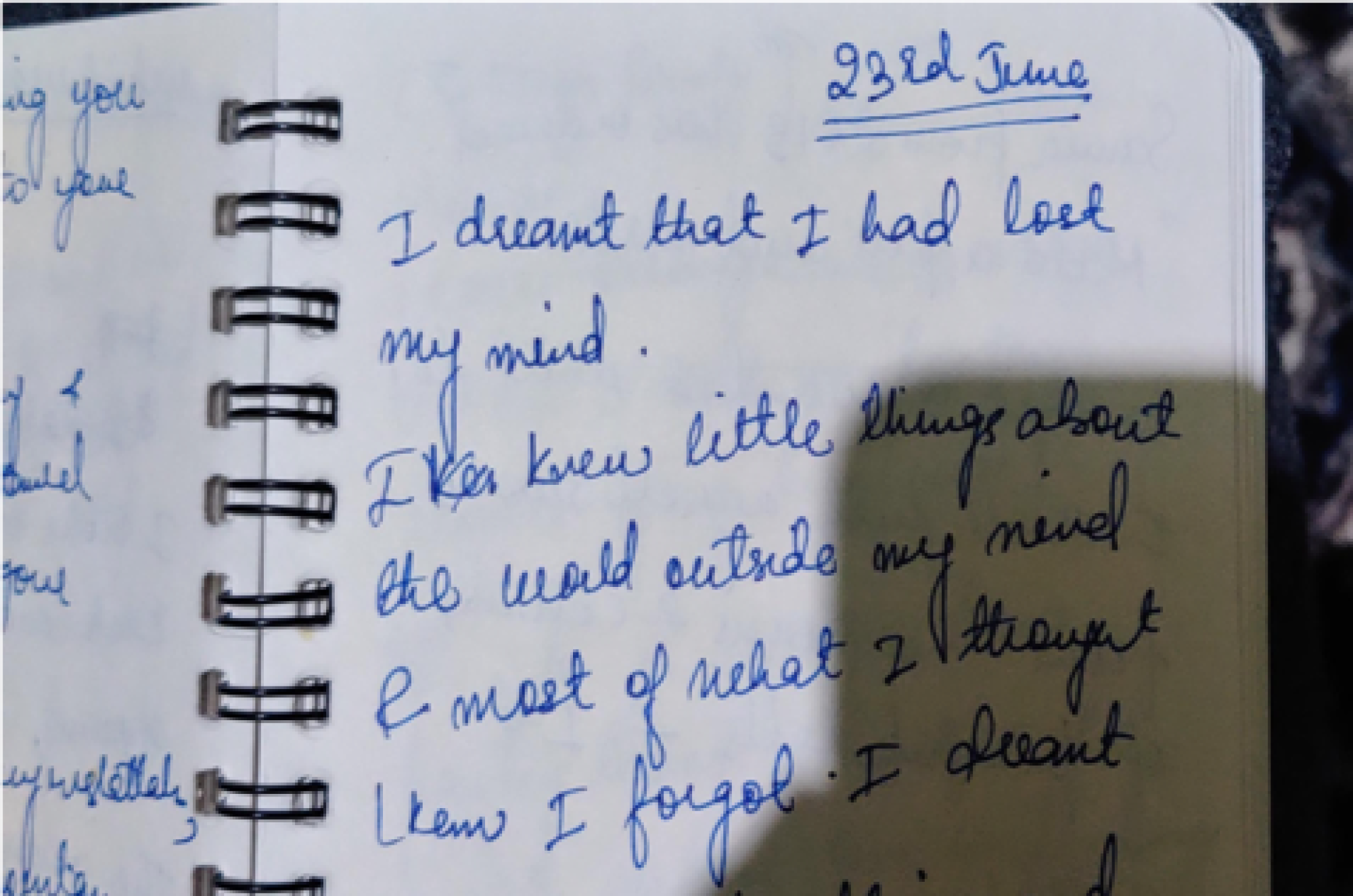

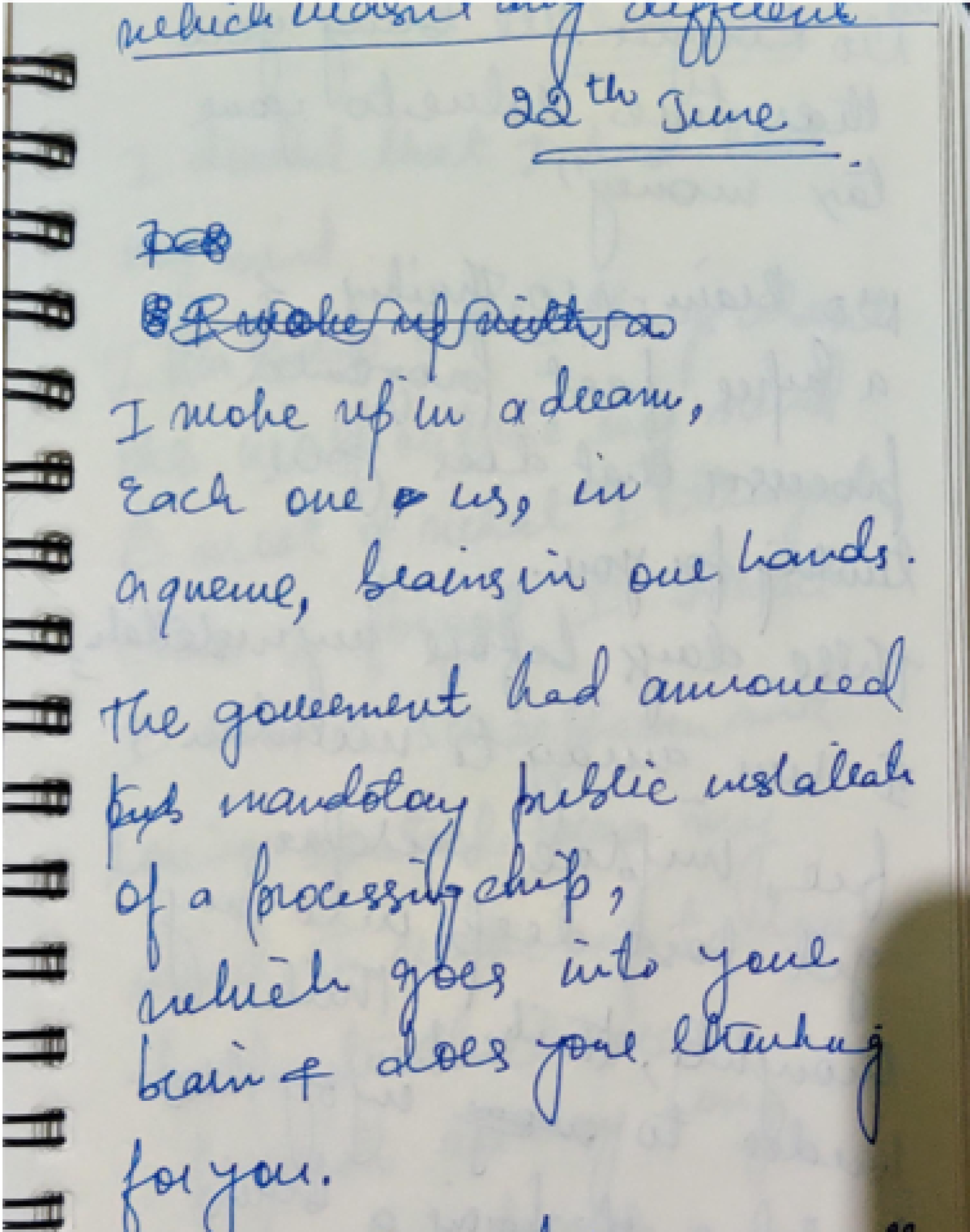

Some images of S’s journal entries

August 2020

N: This is the longest I have lived as an adult in my “home” state which is part of the right-wing belt of India. I have observed many changes across cities here over my short visits in the past decade. Flourishing RSS shakhas (local branches of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the ideological guide of India’s ruling party) in community playgrounds that were just playgrounds some years ago, mass recruitment of residents through WhatsApp groups, disinformation campaigns that vilify Muslims for everything that goes wrong, delusional labelling of all dissidence as anti-BJP conspiracy! There is something I noticed some years ago that continues to haunt me. A distant relative is a senior member of a Hindutva group. On their family bike, I saw police signage and wondered who in their family had joined the police. No one. They got it by virtue of his association; they shared with pride. Hindutva as the Indian state. Indian state is Hindutva.

Lockdown has been relaxed in the city now but recruitment advertisements of these organisations with saffron flags appear almost everywhere. This time last year, the Indian state had laid siege in Kashmir. The state has only sped up settler policies in this pandemic. There are curfew notices coming from Kashmir. I texted a friend asking how things were; she responded, “Same. Barbed wires, checkpoints and what not.” The Indian state has deliberately chosen August 5 marking a year of the siege to lay the foundation stone of the controversial Ram Temple in Uttar Pradesh, a northern Indian state. I am short of words other than being present here; experiencing all this so close has been painful.

Yesterday while I was buying groceries, a young man with membership of a Hindu supremacist organisation that was so flagrantly visible in the insignia on his clothes and bike, came to talk to this boy in eighth grade selling veggies alongside his mother. Their family has particularly been hit by the pandemic, so I choose to buy from them – over the many others with big grocery shops that display fancy food sanitising sprays. The man boasts about going to the mandir (temple) tonight and speeds away. I asked the school kid whether this was about Ayodhya. He nodded, saying the man will leave tonight and reach by early morning. The boy added, rather chirpily, “I would have gone to the bhoomi (land) too and dug the soil for the neev sthapna (laying the foundation stone) had it not been for corona. I will just light fireworks now.” Something struck me then. I think the dying democracy just took a loud gasp through my body. The bodily manifestations of a dying democracy! The dying democracy makes its presence felt off and on; there are anxious nights, days of frantic scrolling on social media, and breakdowns when one is finally unable to control the sheer terror of the present. But democracy, for whom?

How do you write a eulogy for a dead nation?

That evening the city was lit up (we are still in this pandemic) as if it was Diwali but this time marking the victory of religious supremacy. Neighbours were lighting fireworks, playing loud religious music, lighting diyas and fairy lights. My aunt in another city proudly put up a WhatsApp status, waving the saffron flag as they lit up 1001 diyas in their gated largely upper caste society. She is the same aunt whose good morning messages on WhatsApp are now laced with “Jai Shree Ram” and dreams of Akhand Bharat (undivided India). I have elaborately recorded the going-ons of that day in case we forget. In times like these, I do miss my father. Perhaps it was his experiences of growing up in poverty and failure to live up to responsibilities, some imposed and others of his choosing, that made him suspicious of projects that claimed supremacy, certainty, and truth. And here I am holding his paranoia and looking for some semblance of reparative energy. I wonder what he would have said to my aunt or the enthused neighbours. Perhaps just thrown some invectives, drunk his sorrows. In contrast, all I could do is put a black dupatta on the balcony. I think sometimes I protest only to avoid sinking further down. But how long until all is sunk? Am I counting down? Should I?

Some days later, I am in the Kashmir Valley. We are sitting around a bonfire as it is starting to get chilly at nights in the mountains. After a brief pause, a dear friend remarks: jo khud Azad nahi hai wo humein kya Azadi denge? (How will the unfree grant freedom to us?)

Some reflections

In our practice of co-writing and cross-readings which included hours-long conversations, a trail of voice and text messages, reflective pauses, many rough drafts, in-text comments, and overall reflection on each other’s experiences, we identified many moments that haunted us – for instance, everyday conversations in the market, encounters with friends or feeling an incessant sense of dislocation. We began to make sense of our experiences of haunting in the conceptual language suggested by Avery Gordon, in which haunting becomes a bodily knowing that demands “something to be done” (2008; xvi-ii). In doing so and as part of our collective journey, we simultaneously embodied a paranoid and reparative stance (following Eve Sedgewick, 1997). In co-writing, cross-reading, and co-journeying, this stance allowed us to develop a practice that accounts for the generative interaction between paranoid and reparative forms of reading, without pathologising the former or valorising the latter, to develop a practice of reading, writing, and feminist archiving. Such a practice, we propose, emanates from our disparate paranoid stances (for example, identifying absent spaces for solidarity building in our locational contexts and our desire to build them) and seeks to (re)build and hold onto reparative energies otherwise scant in a violent world, and especially in times of physical isolation that many of us continue to find ourselves in.

Our method of everyday archiving thus becomes a feminist meeting place where we seek to dive in the depth and intricacies of “invisible” knowledge “the things behind the things” (Gordon, 2008; 164). This leads us to trace the material and affective footprints of ghostly encounters and their afterlives. For Gordon, “The ghost is not simply a dead or missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to that dense site where history and subjectivity make social life” (ibid.; 8). As evident in our archives, for us too, the ghosts were not necessarily absent, invisibilised, or making their presence felt only through moments of absence. Rather, we were following our embodied sense of haunting/being haunted, often shared and at other times deeply particular, which characterise our contextual complexities and relation to each other. What paths does this open up?

Spatial haunting

Our archival fragments suggest that these are times of spatial dislocation for us, and we locate these feelings precisely by paying attention to the pace of socio-political shifts in our respective contexts. This dislocation and the haunting that follows evokes different responses. S records sensory experiences in Kashmir – the river, the pebbles, the wind – fearing that it will no longer be the same, while N records the banalities that make and perpetuate fascism in everyday life, knowing it is not benign as it claims to be. This act of recording for us becomes witness to the workings of the state and everyday complicity of its citizens. Despite being in our respective “homes,” there is a whiff of homelessness; we sense that something is not right and engage with those moments a bit more deeply. This makes us realise that what is haunting us while different is not spatially bound. These are moments when coloniality makes its presence felt. Dejected, we are looking for connections that can hold us and this brings us together. This is where our paranoid-reparative practice sustains us. We recognise moments of discomfort and/or negative affects – shame, anger, dejection, holding each other accountable (which can also manifest as personal failings) not as undesirable but generative. These are precisely the moments that bring us in community with each other. It is together that we acknowledge the interconnectedness of our struggles that we need to fight collectively, not always, not all the time: after all, these are connections not juxtapositions. But we realise we need to fight them together as gendered subjects resisting a militarised masculinist religious supremacist state. In realising so, we also identify the limits of nation-based activist movements that either co-opt, if not elide, anti-nation-state struggles such as the self-determination movement in Kashmir or water down people’s politics by calling only for internet restoration or critiquing human rights violations without contextualising these in the wider political demands. In our ongoing conversations that precede and persist as we assemble our archives, we speak about this dissonance. Our shared experience of dissonance brings us together to do feminist politics differently and we identify thinking, writing, reading, and archiving as part of our praxis. This allows us to identify solidaristic ways of being and moments that cross borders – they give us a glimpse into the intricacies of each other’s worlds, our desire to forge connections that are neither politically convenient afterthoughts nor list-based parenthetical asides (...Kashmir and so on). On an analytical level, upon reading our archives together, we identify everyday workings of a (post)colonial state and how it does what it does. Together, these insights present openings for us.

Temporal haunting

Shocks and dislocation are also temporal concepts. They complicate the experience of time by slowing it down, speeding it up, or freezing time. In our collective process, we recognise that political events that haunt us are not sudden or even an anomaly but years in the making. Yet, something about their rapidity and the visceral effects they have on us make them shocking. We dive deep into these events and their material effects to understand how they frame our experience of time; why do they shock us? Together, we realise that colonial and fascist projects seek to introduce a linear temporality: “Kashmir will now see development; we are undoing historical wrongs and moving towards days of glory; acche din aayenge (good days will come).” They also take control over our experience of time by prying on it. S’s social media interactions that take up long hours and continue to have an impact even after these conversations have ended illustrates this. In contrast to the linear temporality the state seeks to set, our collective sense of dissonance is a prolonged temporal experience that challenges precisely this linearisation. It necessitates that we remain with our experience of dissonance and engage with the possibilities it gives rise to. We take it slow; we give it time and decide to do this collectively through intensive processes of co-writing, cross-readings and archiving. This entails careful historicisation of the political events that shook us: rapid settler colonialism in Kashmir as a result of longer colonial histories, the classist, casteist underpinnings that made migrant workers walk barefoot for hundreds of kilometres only to be sprayed with disinfectants. Implicit here is a politics of refusal that disavows progress and development narratives of time and embraces uncertainty and dislocation. Overall, this means that such reparative moments, rather than always already present and somehow waiting to be excavated, are precisely the ones that need to be built and sustained in our archives, reading, and practice of being.

Changing forms of spectres

For us the act of border crossing towards finding possibilities of feminist solidarity is not about transcendence. We do not suggest that somehow, by embodying a paranoid-reparative practice of archiving it is possible to leave behind relations of power that co-constitute us and be free of their messy entanglements (Trisal, 2020). We also do not see this practice as a “fix” to our confusions or an exercise that has the potential to reduce our colonial realities as ones that operate from the same location, power, or privilege. Or that it is possible to mobilise a reparative practice to claim less complicity or self-enunciation of “doing good” (Wiegman, 2013) or “less bad.” Indeed, this would be antithetical to the feminist practice of reflexivity that we are hoping to embrace. Instead, we interrogate these thoughts from the openings offered “from our contexts” rather than “beyond” them. In this sense, we sit with these discomforts and hold each other through them in the hope of making connections where none or feeble links exist.

We realise that it is not only the structural aspects of colonial agendas that subjugate us. Our everyday experiences are also peppered with ghosts of all shapes, and their remnants. These could be flashbacks from events of spectacular violence that took place in the past or anticipating events that may happen in the future. We have also inherited some hauntings of/in our families: loss of family members due to thin medical services or complicity of those we know in the fascist project. Some of these ghosts have material footprints – the deaths, night firings, camps dotting the Shankaracharya hill in Srinagar, military presence, blood on the streets, utensil beating. They engender cognitive and affective dissonance in us and continue to have a sustained impact on our lives. They find space in our personal reflections, these archives, our conversations and writings, and how we engage with the world. While grim, our experiences of haunting allow us to speak with each other. We share them with each other in the hope that we can trace their interconnections. We map them, track their footprints and how they co-constitute each other, and imagine ways to sever those links. This “doing” becomes a moment of solidarity that we want to hold on to. The ghosts that haunt us inadvertently bring us together.

Concluding remarks

In India and Kashmir, the public imagination is manufactured to posture 2019 and 2020 as landmark years in the regions’ histories. We understand these years in light of the events that transpire, but more so by the responses they churn and how they influence our worlds. These events, responses, and influences, although varied for us, are ensnared in our circumstantial but intertwined colonial pasts and distinctly shape our lives. Because we remain preoccupied with being witnesses to these events, little affectual space in our lives is left for addressing our thoughts, feelings, grievances, or the need for productive border-crossing solidarities. In this context, our archives – field notes, journal entries, conversations, and cross-readings – emerge as a way of documenting colonial engenderings and ruminations that animate these years. It is these intimate notes that we share, discuss, and investigate in this paper. We intentionally situate ourselves in the current – its visceral, political, and material – to trace its connection to our historical – the deeply embedded. In the process of doing so, we offer a raw and uninhibited repository of our intimate responses: they are the “hauntings” meted out by the colonial ghosts of our homelands, and through these hauntings we build (rather than just discover) a meeting place where reading and writing translates to intimate relationality.

While we set out to locate the “invisible” knowledge, “the things behind the things,” we do not claim that we always find them, or that this undertaking is a conclusive feminist roadmap to solidarity. We may find only little “closure” (if such a thing exists). But our larger attempt is that of observation, confrontation, and conversation. We yearn to understand our responses and our histories to make sense and take some resistive control of the shape our hauntings take. More importantly, we seek camaraderie in doing so. Through our practice of reading and writing, we navigate the cacophonies of our contextual and locational conundrums to imagine newer ways of being together that can engender material transformation. This paper is an attempt to materialise this relationship. We aim to continue building bridges, crossing borders, and in doing so confront our colonial pasts one small act at a time, but all the time. In the face of a vast, far-reaching, deeply embedded, and legitimised state oppression; a transnational and intimate building of solidarity can create reflexive spaces towards nurturing and sustaining decolonial movements.

Anzaldúa, G., 1999. Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

Asif, M., 2020. The Loss of Hindustan. Harvard University Press.

Bhat, B. and Mugloo, S., 2020. Kashmir’s Displaced Struggle to Survive Amid COVID-19. [online] The Diplomat. Available at: <https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/kashmirs-displaced-struggle-to-survive-a... [Accessed 11 February 2021].

Gordon, A., 2008. Ghostly Matters. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Halder, T., 2019. Kashmir’s struggle did not start in 1947 and will not end today. [online] Aljazeera.com. Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2019/8/15/kashmirs-struggle-did-not-s... [Accessed 11 February 2021].

JKCCS, 2018. Annual Human Right Review 2018. [online] Srinagar. Available at: <https://jkccs.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Annual-Report-2018.pdf> [Accessed 11 February 2021].

Kabir, A., 2019. Chandrashekhar’s azadi with swag: The fabulous mystique of the Bhim Army chief. [online] Scroll.in. Available at: <https://scroll.in/article/947721/chandrashekhars-azadi-with-swag-the-fab... [Accessed 11 February 2021].

Mehta, A., 2020. Embodied Archives of Institutional Violence and Anti-Racist Occupation – Reading Julietta Singh’s ‘No Archive Will Restore You’ in the University. [online] feminist review. Available at: <https://femrev.wordpress.com/2020/08/28/embodied-archives-of-institution...

Menakem, R., 2017. My Grandmothers Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Central Recovery Press.

Nagar, R., 2019. Hungry Translations: Relearning the World through Radical Vulnerability. (1 ed.). Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Rao, R., 2020. Nationalisms by, against and beyond the Indian state. [online] Radical Philosophy. Available at: <https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/commentary/nationalisms-by-against-and...

Roy, A. 1997. The God of Small Things. Penguin Random House.

Sedgwick, E., 1997. Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading; or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Introduction is About You. Novel Gazing: Queer Readings in Fiction. Duke University Press.

The Wire. 2020. Delhi Riots Death Toll at 53, Here Are the Names of the Victims. [online] Available at: <https://thewire.in/communalism/delhi-riots-identities-deceased-confirmed> [Accessed 11 February 2021].

Trisal, N., 2020. “The Kashmirization of India”: Comparison, Solidarity, and “Paranoid” Reading. [online] Association for Political and Legal Anthropology. Available at: <https://politicalandlegalanthro.org/2020/08/14/the-kashmirization-of-ind...

Shamim, F., 2020. Culture of Institutionalised Impunity and Violence in Indian Occupied Kashmir (IOK). [online] Ssii.com.pk. Available at: <https://ssii.com.pk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Culture-of-Institutionali... [Accessed 11 February 2021].

Wani, R., 2020. Why Kashmir Faces the Greatest Existential Battle in Past 500 Years. [online] Storiesasia.org. Available at: <https://www.storiesasia.org/why-kashmir-faces-the-greatest-existential-b... [Accessed 11 February 2021].

Wiegman, R., 2013. 2013 Duke Feminist Theory Workshop Keynote Robyn Wiegman. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JwPHNTO3ZBM&ab_channel=DukeWomenStudies> [Accessed 11 February 2021].