Resisting Ableism, Queering Desirability

الاهتداء الى موضع العلّة

Locating sickness

When we think about disability justice, we unequivocally remind ourselves that the first principle of disability justice, as written by Sins Invalid, is “ableism, coupled with white supremacy, supported by capitalism, underscored by heteropatriarchy, has rendered the vast majority of the world ‘invalid.’” With this notion anchoring our collectively thinking, we know that queerphobia/transphobia and ableism as well as other systems of oppression such as racism and colonialism intersect and influence the lived experiences of queer folks at the margins. But, beyond oppression, we know there is also resilience, joy, and great things that happen at those intersections. As the wonderful black queer disabled activist Eddie Ndopu recently tweeted: “Intersectionality is not just a question of standing at the crossroads of compounded inequalities – it is also about the ways in which one body, one human being can inhabit compounded genius. To be black, queer and disabled, all at once, is to embody genius, multiplied.”

In her speech “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” Audre Lorde says:

much of Western European history conditions us to see human differences in simplistic opposition to each other: dominant/subordinate, good/bad, up/down, superior/inferior. In a society where the good is defined in terms of profit rather than in terms of human need, there must always be some group of people who, through systematized oppression, can be made to feel surplus, to occupy a place of the dehumanized inferior.

As queer folks, folks of colour with disabilities, we redefine and break these supposed moulds of “normalcy” through our everyday existance, resistance, and persistence.

Timeline at Work

In 2018, Ghiwa from Kohl, and Nelly and Karine from DAWN Canada, discussed applying for a call of submissions to the first global feminist LBQ Conference in Cape Town, South Africa, in July 2019. We had talked about how we replicate power dynamics and systems of oppression within queer communities, and asked ourselves (and each other) how we could do better. We were aware that ableism seeps into queer communities, especially around desirability and bodies, and that these dynamics are replicated within queer communities. We saw our respective work as complicit with each other’s, and we were motivated by a joint desire to anchor disability justice in the activism that we do and the frameworks that we operate under, especially in the contexts of West Asia and North Africa queer movements. To us, intersectionality also entails questioning who talks about queerness and disability, as these conversations can be and often are dominated by a white discourse. By naming power, we can hope to center folks who are at the margins of disability and feminist thought.

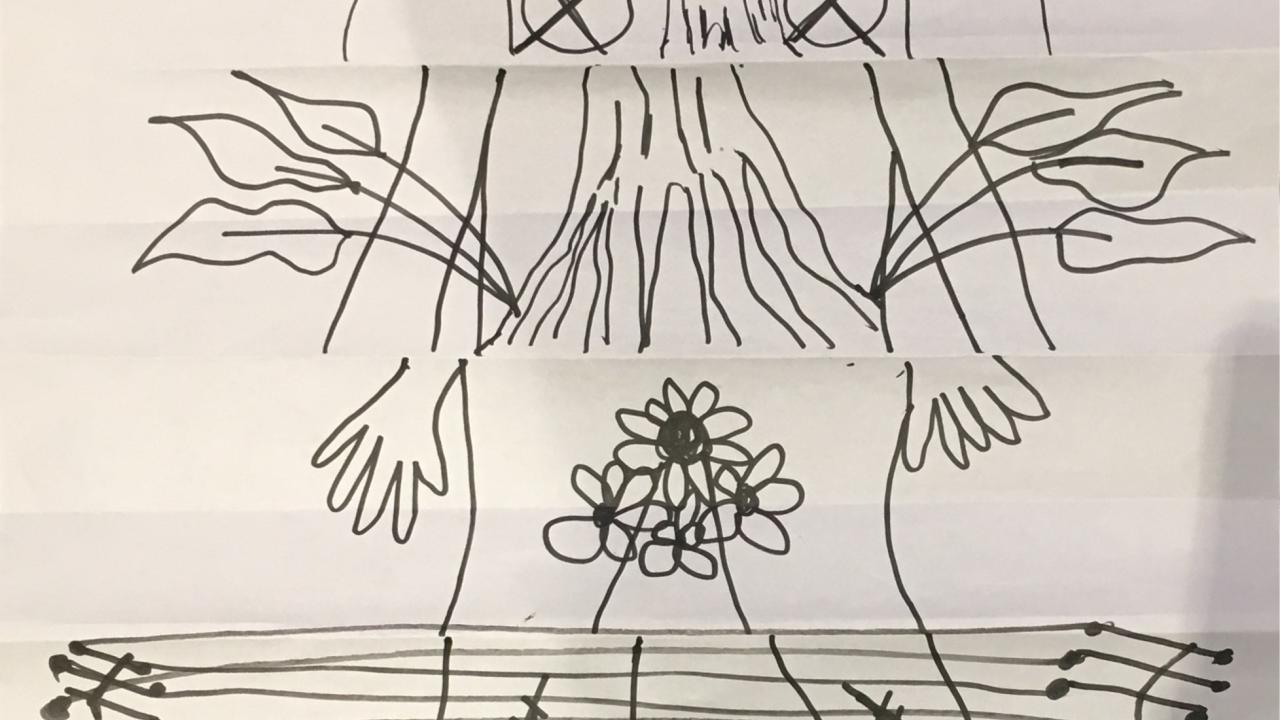

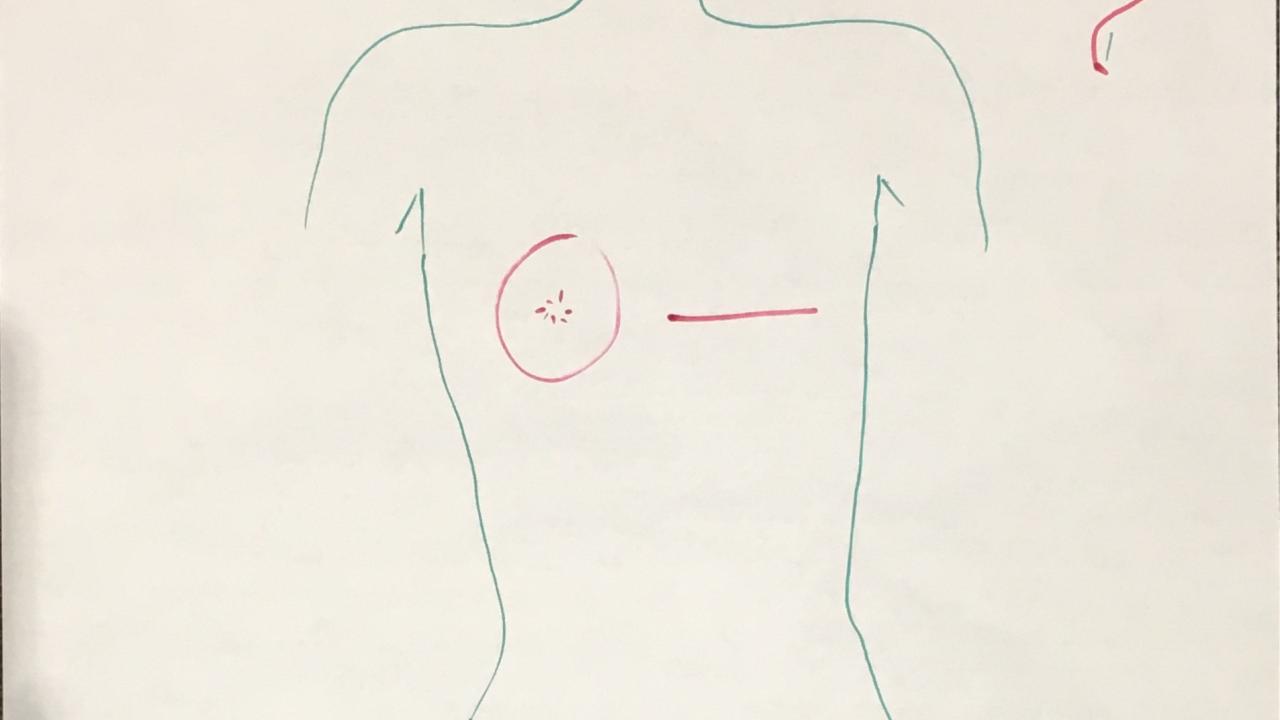

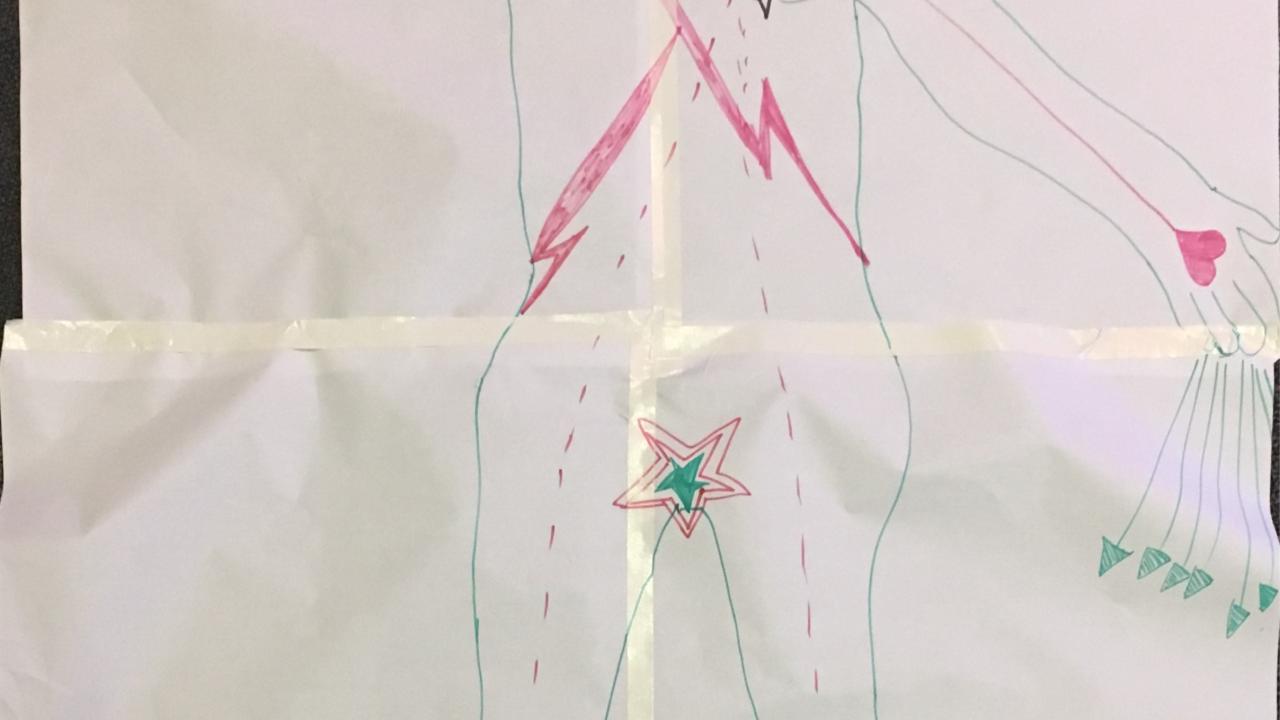

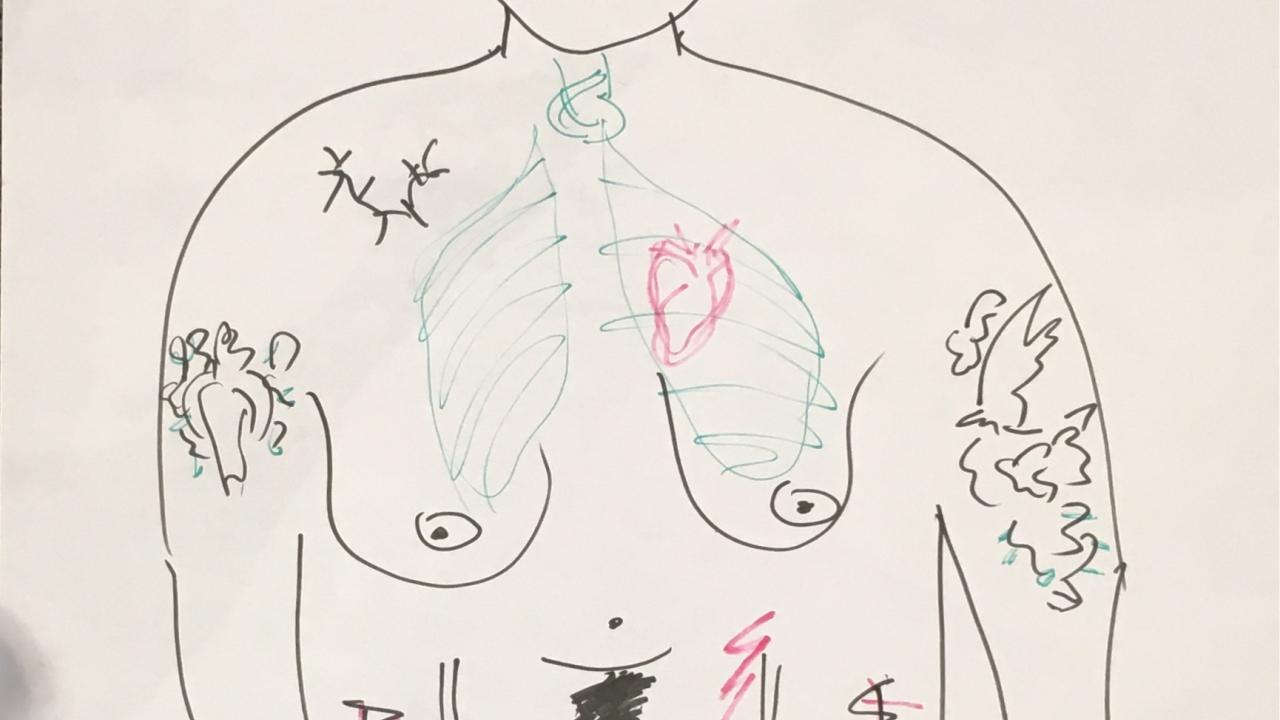

At our workshop at the conference, we encouraged people to do a free-write on their experiences. These moments, punctuated by collective reflections, brought deep, sometimes uncomfortable/discomforting experiences with disability to the surface. We witnessed ourselves and each other come into and understand what disability meant to us, to them. Disability is a spectrum, and our understanding of it is sometimes limited. Even within queer communities, when we are at the forefronts of movements, we still have our own ableism to contend with. Another important tension the workshop brought forth was the privilege of not digging deep, of remaining in comfort, as an ableist practice. We found going to these uncomfortable places to be part of disability justice activism. And so, we drew bodymaps out of our discomforts.

Later that year, we opened a call for papers, hoping to build on the workshop and publish a special issue in the first quarter in 2020. Not only did we relax our publication timeline and pushed publication until later in the year, but we also felt compelled to reopen the call because of the intersections of disability, the economy, and COVID-19.

Our respective/collective realities

Although the deadline extension and reopening of the call did not change much in our initial conceptualization of the fabric of the special issue, we also wanted the process of publication to reflect our current realities. We were all hit by lockdown measures that affected a lot of people with disabilities by cutting their access to communal spheres (education, proper care and healthcare, community work) even further. Because of the particular context of Lebanon, where Kohl is based, we (Kohl and DAWN) had long conversations about the economic collapse that has been playing out throughout 2020 in Lebanon, and what it entails for the publication, whether in terms of content or labor behind the scenes. We embraced rupture in the editing process itself because of the material circumstances we were living on a global and transnational scale.

With lockdown, not only is access to certain services more difficult, but such a configuration also exacerbates mental health issues. In our work together, we tried to deconstruct and do away with our capitalist idea of productivity pre-COVID-19 – an ableist, yet very present notion tied to shame and low self-worth. We were very aware that we did not want to preach what we do not practice, so we actually slowed down, and thought about what it means to adopt a different pace as praxis. The publication process, therefore, took us longer than planned because we shifted our perspective away from ableist productivity.

Another aspect of productivity we would like to undo is the notion that collaborators’ contributions are only valid or relevant if they go through the publication process with the finality of a physical, tangible “product” that can be showcased in legible or consumable formats. We find this special issue to have been shaped by all workshop participants and authors, even those who did not submit anything or dropped out at one point of the editorial process, as well as the communities that have sustained and nourished us. The context of COVID-19 challenged the urgency of editing deadlines. We understood that sometimes, we just have to let go. This does not erase people and their contributions; they are felt throughout the process and the issue.

We went back to the personal as political. We, as people behind Kohl and DAWN, are also part of this process. The course of the workshop and publication is contingent on our labor as well, and we cannot be divorced from our material realities, especially as people who also find ourselves thinking, talking, embodying disability justice, even if from different positionalities. Slowing down was also for our sake, which then became for the sake of the community. We extended kindness to ourselves so we could practice kindness with each other.

Anchoring in Contexts

This issue on resisting ableism, queering desirability is our attempt at building on and adding to the rich thinking that shapes disability justice, with interconnections between disability, race, gender and sexuality where we center queer disabled people of colour. Because, if COVID-19 has highlighted anything, it is that white supremacy was always hell bent on erasing us. Lockdowns reinforce rabid capitalism’s role in our oppression. But our care for ourselves and for our communities, and our commitment to question ourselves and always do better, stretch and explode the tight boxes that capitalism, white supremacy, ableism, and queerphobia try to confine us in.

We are excited for everyone to discover the brilliant writings in this issue and want to continue this important and expansive dialogue of care and love within our queer and disabled communities.