“We Kindled the Fire and it Enkindled Us:” Three Poetic Articles by Leila Baalbaki

Introduction & Translation by Maru Pabón. The following poetic articles are published with consent by the author. Copyright Leila Baalbaki “All Rights Reserved.” They were first published in al-Dustur, 1973.

Maru Pabón is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Yale University. Her manuscript in progress examines the Third-Worldist desire to construct the “voice” or “language of the people” across Palestinian, Cuban, and Algerian poetry from the late 50s to the early 70s. Focusing on the writers Mahmoud Darwish, Fayad Jamís, and Jean Sénac, the project likewise makes visible the networks of circulation, translation, and exchange that link these poets together. She is also a translator from the Spanish, Arabic, and French.

photo-2022-09-22-16-35-35_2.jpg

Photo from Leila Baalbaki's personal collection.

In 1973, the Lebanese cultural magazine al-Adab published a special issue titled “Our Writers in Battle” reflecting on the October War, which had culminated just a few months prior. In the moment, not all endings appear as triumphant new beginnings, but the conclusion of the October conflict was quickly dressed in the language of rebirth and resurrection. The victories of the Syrian and Egyptian forces over the Israeli state reestablished a sense of confidence in Arab identity that had been rendered moribund in the aftermath of the 1967 June War. Suhayl Idris, committed [multazim] writer and editor of al-Adab, opened the special issue by claiming that the war had inaugurated “a new history for the Arab people.” How this new history had begun to be written – what were its leading forms and features – was the question he invited authors to answer.

In a poignant gesture of unity, many authors did answer: almost a hundred, and from twelve different countries. Adonis, Taufiq al-Hakim, Nizar Qabbani, Mahmoud Darwish, and Naguib Mahfouz were just some of the well-known figures who contributed texts composed during the conflict to the special issue, which collected analytic articles, short stories, and poems of varying genres and forms originally published in periodicals across the region. In the front cover, among the listed Lebanese contributors, a particular name stands out: Leila Baalbalki.1 Stands out not only for being one of just a handful of women featured in the issue, but also because her name is a reminder that 1973 also marked the ten-year anniversary of a momentous event in the history of Arab feminist literature: the publication of Safinat Hanan ila al-Qamar (Spaceship of Tenderness to the Moon), Baalbaki’s first and only collection of short stories, and the ensuing legal case against it.

As the author of the novel Ana ahya (I Live), published in 1958, Baalbaki had been the first female Arab writer to bring existentialist thought to bear on the condition of women in Lebanon. Born in 1936 to a Shia family in Beirut, Baalbaki came of intellectual age at the height of a total transformation of the social function of literature: writing had begun to be figured as a weapon in all sorts of sociopolitical struggles across the region. As Kifah Hanna and Margot Badran have noted, already by the end of the mandate period the feminist movement was buttressed by a particular focus on the development of literary and intellectual agency among (primarily bourgeois) women.2 The late 50s – years shaped by the rise of Pan-Arabism, Palestinian cultural resistance, and diverse decolonization struggles – saw the tightening of the connection between intellectual autonomy and the empowerment of women. Lena, the protagonist of I Live, is defined precisely by the resounding strength of her existential convictions and assertions of identity; the itineraries of her relentless quest for self-knowledge structure the social space of the novel. Lena’s vicious critique of the bourgeois patriarch as authoritarian sovereign inspired countless writers of Baalbaki’s generation and beyond; the novel placed Baalbaki at the forefront of what Hanan Awad has called the first “revolutionary feminist movement” in Arabic literature.3 Hanan al-Shaykh and Colette Khoury have both named her as an important model, and it is difficult to imagine that the canonization of a novel like Latifa al-Zayyat’s 1960 al-Bab al-maftuh [The Open Door] would have been possible without the reception of I Live.

But just as Baalbaki’s novel drew positive attention from sectors of the Arab literary establishment, it also inflamed the ire of her detractors. When, in 1963, her collection Spaceship of Tenderness to the Moon was published, that ire led to overt persecution. Following the publication of a moralistic review, written pseudonymously in the Egyptian magazine Sabah al-kheir, the collection was censored in Lebanon and Baalbaki was taken to court for the supposed indecency of several stories.4 The trial was the first in the history of Lebanon; a writer stood accused of “offending public morality” for writing scenes of sexual desire from a woman’s perspective. Although Baalbaki was acquitted, the experience was harrowing. According to the critical consensus, the trial marked the end of the most significant chapter of her literary career.5

But here another end that bled into a new beginning: Baalbaki turned to journalism. Throughout the 60s and 70s, she published frequently in journals, magazines, and newspapers on current affairs and events that moved her. These could be personal or political; often, as the three articles [maqalat] she contributed to the 1973 issue of al-Adab confirm, the boundaries between the two spheres were blurred. Significantly, so was the line between documentary observation and literary creation. “I Attended the Birth of Dawn,” “My Beloved Walked on the Surface of the Water,” and “O Diplomacy, You Will Not Extinguish Our Fire” – these short, generically experimental texts, first published in al-Dustur and translated into English here for the first time, belie the narrative that Baalbaki ceased all literary activity after the 1963 trial. They also represent an important reconfiguration of her conception of freedom.

I Live, as the title immediately declares, is a strident assertion of radical individualism. In the eyes of Lena, freedom is to be achieved via practices of self-possession. (The novel begins with the lines: “I wondered, as I crossed the sidewalk between the tram stop and our house: to whom does this warm hair belong, this hair strewn across my shoulders? Is it not mine? Do not all beings have hair, with which they can do as they please?”)6 From this assertive beginning, which takes the body as the locus of the struggle for freedom, the novel develops an ethics of revolt in all directions, against any authority that would hinder the quest for Lena’s authenticity, be it father or political party. Although the forcefulness and seeming indiscretion of Lena’s revolt led some critics at the time to diagnose the novel as nihilistic, recent reevaluations have drawn different lessons.7 A pertinent one for our purposes: that the struggle for freedom, and freedom in the form of decolonization, begins with the self but continues outward, consuming the family, the state, and eventually – hopefully – everything in its path.

If this lesson was already contained in nuce in Baalbaki’s I Live and Spaceship of Tenderness to the Moon, then the al-Adab articles represent its mature and militant expression. These texts, whose occasionality is at times sharpened, at times concealed, by the Olympian distance of allegory, present us with a conception of freedom still linked to the female body and its intimate trials. But this is a body jostling her way through crowds, dissolving the “I” to which so much pride and meaning had been attached into a kinetic “we.” Through the use of cosmological metaphors and vibrant symbolic language, the jostling, collective body of the revolutionary crowd is offered in these articles as a new origin point for the struggle for freedom; the individual is dialectically redeemed because she moves within it. This is a crowd fighting explicitly for the liberation of Palestine (in “I Attended the Birth of Dawn” and “O Diplomacy, You Will Not Extinguish Our Fire”), and foregrounding the contributions of women to the fight for a new, egalitarian world. In these texts, the ecstasy of romantic love responds to the thrills of social upheaval; the unbearable pain of love lost echoes the agony of political betrayal. Martyrs are named as lovers and enemies as the Zionist state. When domesticity is extolled, as in “My Beloved Walked on the Surface of the Water,” it is through the language of social reproduction; when motherhood is invoked, it is as a peg whose absence would cause the entire contraption of the material world to topple. One may find remnants of an inherited cultural discourse that gives precedence to masculine valor, but the attention paid to female kinship and the positioning of female labor as an essential precondition for the travails of the male fighter attest to the ways Baalbaki expanded the feminist imaginaries of her time. At the same time that the category of the male militant is idolized, it begins to be demystified – revealed to be socially mediated. This shift of Baalbaki’s articulation of feminist demands, which echoes what Kifah Hanna has referred to as the transition from an individualist feminist paradigm in Arabic letters to a relational one,8 is here made all the more striking by the formal and aesthetic innovations it implies.

When I first read Baalbaki’s articles in al-Adab, I took them for prose poems. The symbolism, the recurring apostrophes, and the structure and cadence of the lines all guided my interpretation – not to mention that the prose poem as a genre was very much in vogue in Lebanese literary circles around 1973. It wasn’t until I corresponded with the author, via her daughter-in-law Zeina, that I learned they were envisaged as journalistic articles. But Baalbaki responded positively to my generic confusion; she was intrigued by the idea of her articles as poems, and mentioned that her father was in fact a poet. “An innate talent,” she wrote.

I have thus come to think of these three texts as “poetic articles” whose formal and generic instability offers noteworthy insights into the modes of writing that mediated the sense of living through the “new history” of which Idris wrote. The Palestinian struggle, the assassination of leftist leaders, and the failures of political reformism are all claimed in Baalbaki’s 1973 articles not only as Pan-Arab issues, but as properly feminist and anti-colonial concerns. The articles alert us to the significance of this historical shift in feminist discourse as much as they remind us that Baalbaki remained an influential figure in the Arab literary world well after the trial with which her name became synonymous. I hope that in revisiting this period in her career with my translations, I can encourage others to do the same.

The following poetic articles are published with consent by the author. Copyright Leila Baalbaki “All Rights Reserved.” They were first published in al-Dustur, 1973.

I Attended the Birth of Dawn

In the beginning was the face––

I dove into a delightful dream.

Suspended in grey space, I no longer tasted dust in my mouth. A drowsy frost settled on my fingertips and toes. No ground below me, no cement nor tiles; I became a cloud.

The face from the beginning now floated on mine and I could see the sunrise in its eyes: two springs of flowing light.

Oh,

don’t ask me what I’m talking about.

Grant me the blessing of delirium.

I’m trying, I’m trying to testify.

With great effort, that day, like all days, we tore ourselves from our beds. We dragged our bodies to the streets looking for food and drink, we went into the restrooms, showered, and bought new shoes. The man among us, to prove he was a man, skillfully shaved off his beard. The women flashed their breasts and slathered tons and tons of red on their mouths and thighs and nails.

See, I’m trying to explain:

That on the sixth of October, and the day was a Saturday, in the afternoon, with these two hands and these two eyes, I attended the birth of dawn.

Oh,

this earth was drowning in darkness and drought. Its people were fig trees––worm-eaten, torn-up. The crops they yielded yearly, the crops they yielded always, were humiliation, oppression, and loss.

The earth trembled a little; it didn’t rain. Refreshing cool breezes migrated toward us from all corners of the world, but there was a storm brewing in my head.

Yes, of course I’m relating what I saw. Hold your breath, summon the writers of epics:

From the depths of persecution and torture, from the blackness of oppression,

a brown Arab rebel sprung from the earth’s womb and began to walk.

Yes, with this throat, with my throat unable to scream, that’s how I saw him:

he was born and he began to walk.

A miracle: he moves his feet. He faces forward, lifts one foot, then another, and walks. That’s how he advances.

Ask the face that floated above my own, above the clouds––he’s the martyr and witness.

I gasped.

No––

Have them listen to the news bulletins, the battle results, the military analyses.

The face grows. I now see his neck and chest high above, drowning in a pond of blood, and I recognized him I recognized him. A crime took place on this street, they stabbed him in the back. They crossed the sea, disembarked at the beach, and descended into the dirty alleyways. They climbed the stairs, rang the doorbell, and murdered him. The eyes of the city’s people were collapsed sandstones worshiping their idol, fear.

So please:

I ask of those now lighting holy fires in every inch of this land that thirsts for courage, redemption, and dignity,

I ask of those heroes marching forward in valleys, deserts, and hills,

of those men who returned to us after an eternity of humiliation and disgrace.

I ask of them,

I implore them,

to raise their weapons over the body of Kamal Nasser,9 quietly, humbly, bravely,

so that fields of flowers grow over the martyr’s body, so that we return to the scent of laurel in the prairies, and so that atop Mount Carmel olive trees return to us.

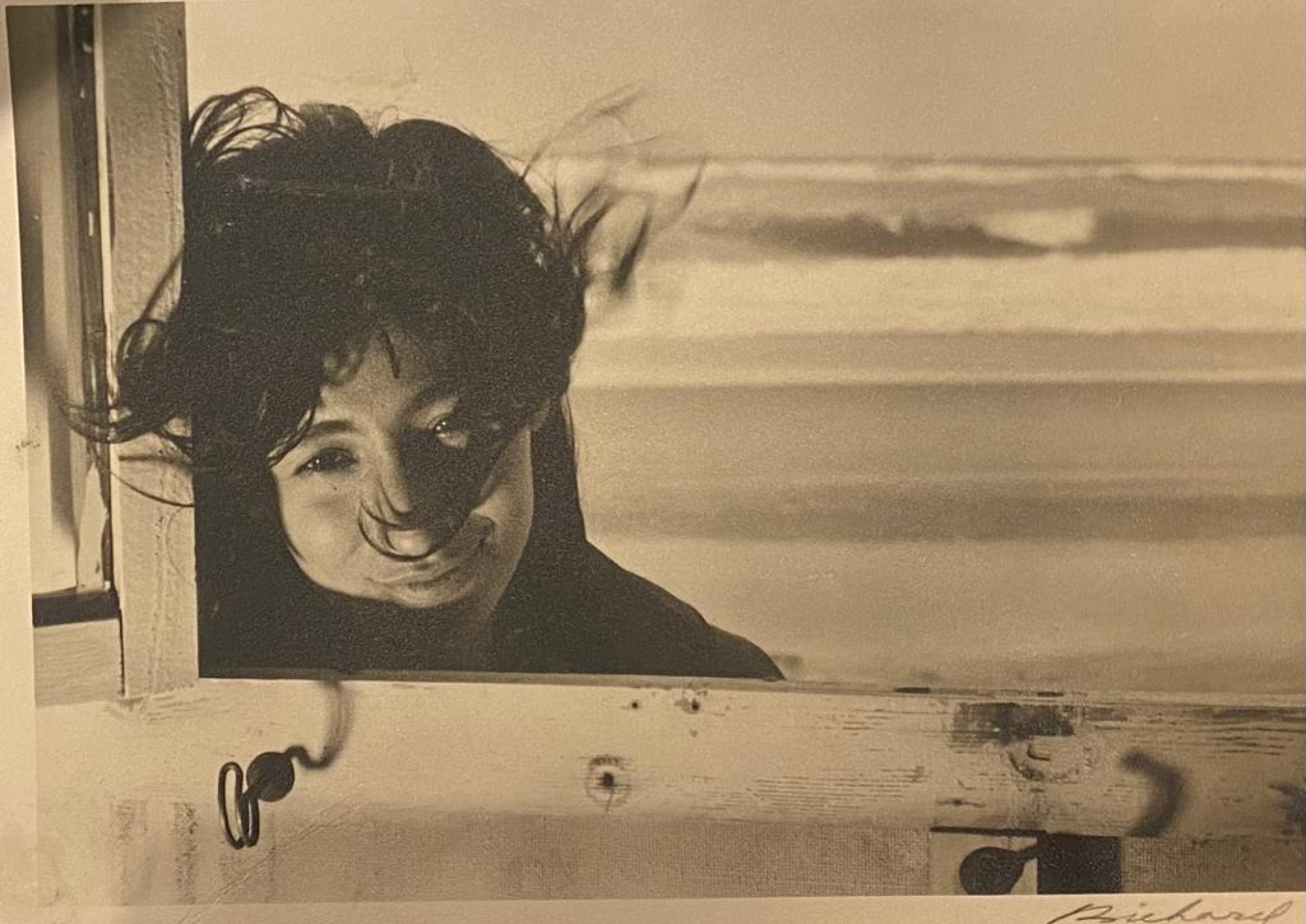

photo-2022-09-22-16-35-35_1.jpg

Photo from Leila Baalbaki's personal collection.

My Beloved Walked on the Surface of the Water

O beloved––

You, now at war in your large and fertile land; you, surging through my arteries and lodged in the corners of my eyes.

Because I am obsessed…

Because I am reckless…

Because with you I became mad with joy, let me run to you. My body has come to life, and you know that I was born paralyzed, the paralyzed daughter of a paralyzed mother and a paralyzed father.

Let me break the sound barrier, travel through deep space, shatter the snouts of serrated missiles, wrap my body around the bellies of airplanes. Let me descend into the mouth of your rifle, scale your sharpened sword, wipe the beads of sweat from your forehead; for you, let me become a garden planted with grape vines and apple trees over which the night passes slowly, and the moon shines early, and where I provide wine and shade.

O rebel,

O marvel,

I waited for you on a rock at the shore. I glanced at the sea for a moment, and I swore I saw you parting the waves with your gun and walking on the water. You were truly in front of me walking on the surface of the water.

Where did the voice that exploded inside of me come from?

How were you able to strip the rubble and mold off my face?

How were you able to give me back my sight?

There I am, I see you coming as the white Mediterranean Sea swirls with submarines, with warships, aircraft carriers and merchant ships, with fish and fisherman, with seashells, with soft seaweed and twilight. You are a breeze crossing distances and dangers; I saw you coming.

The surprise provokes a pleasant chill, which reminds me: the old women asked me to send you their prayers, and to tell you they’re knitting you woolen socks for the cruelest days of winter.

Let me tell you, also, that we keep you in mind as we go on cooking, that we think of you as we eat and peel garlic and onions, and as we wash the children’s feet. We remember you as we drink, and with increasing fervor; as we rush to work and get drunk without knowing why, as we cry for you and as we jump for joy. We walk brazenly among the people after shedding our modesty, never embarrassed to go on with our daily chores. Our lives are the bones in your back. We are the womb where you grow and from which you are born.

Listen to me,

the day I carried my belly––after the dreadful war that tore us apart—the day I carried my swollen belly to the Damascus Gate, that day my beloved died.

I searched for my dead beloved on faces burned with napalm and in aching eyes. I searched for my beloved inside the leaders. I searched for my beloved in the newspapers’ classified ads. I searched for my beloved in the lies. I searched for my beloved in speeches, in the scent of betrayal and cowardice. I searched for him in children’s eyes. I found him buried in the eyes of children.

How could you, O sorcerer, O beloved, come back to life in this way?

Give me your arm, O man, so that I can crawl into your wound and explode.

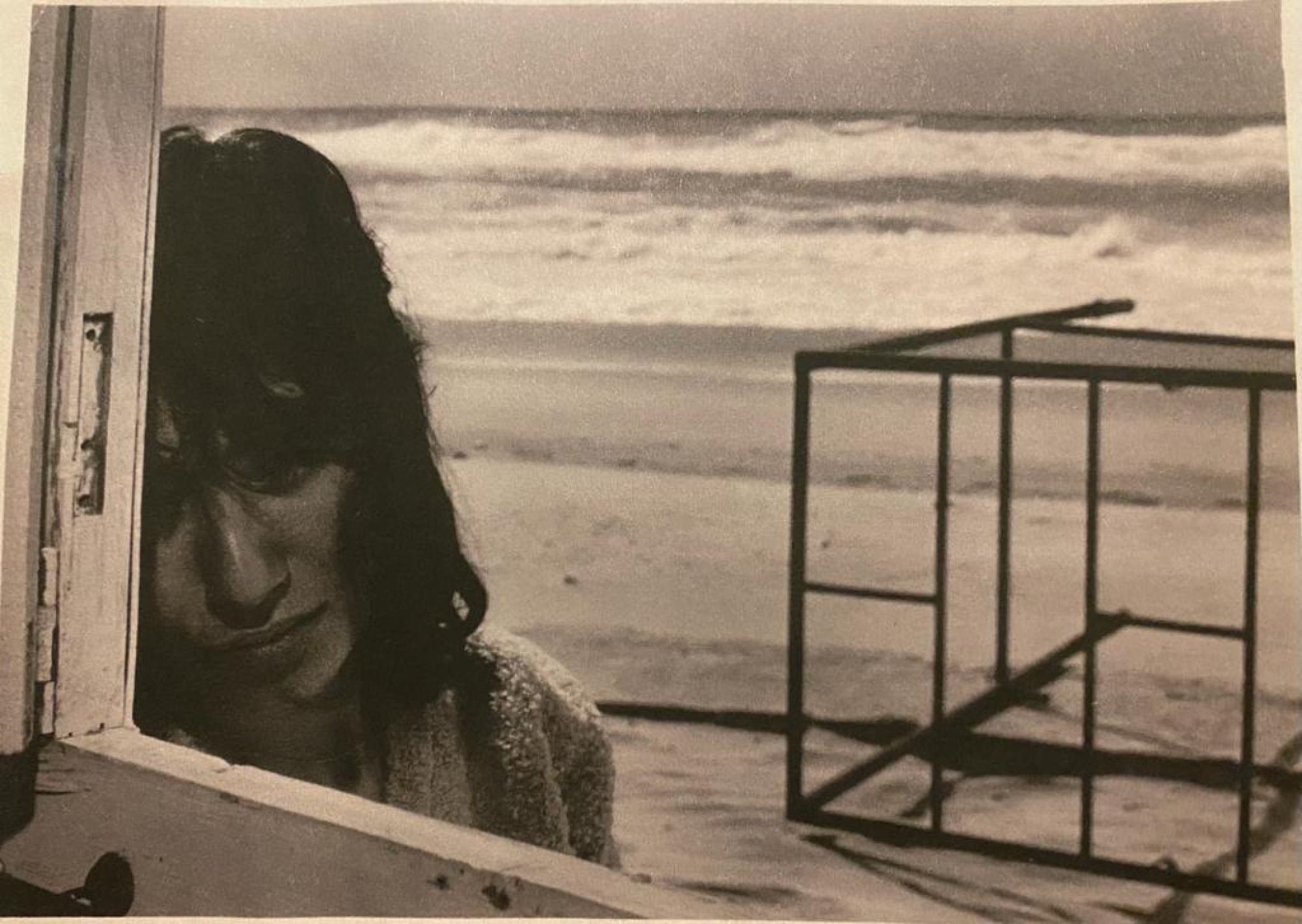

img-4019.jpg

Photo from Leila Baalbaki's personal collection.

O Diplomacy, You Will Not Extinguish Our Fire

I hear a commotion––

I hear diplomacy’s footsteps.

O Diplomacy, you are on the opposite bank of the world, and we ignited the fire.

Again and again we accepted your peace: we brought it into our chests, we lodged it in our spines and in the pupils of our eyes, we mixed it with cooking salt into water, this deceitful peace.

O diplomacy reigning on the world’s throne, so fiercely did we attach ourselves to your sacred peace that it became a malignant illness coursing through our limbs and bones, through our arteries and pores. In terrible silence your peace killed us with ease. We began to shrivel up, we fell like corpses, the smell of defeat emanating from our bodies. Meanwhile the world rejoiced in spitting on us while trampling our stomachs, rejoiced in coming up with insults and names for us, in encouraging Israel to abuse us, torture us, kill us––to annihilate us. Your peace became a stain on our foreheads; our necks bowed under its weight. As punishment for accepting it, the world smacks us on the head.

The fire––

the fire, the fire,

We kindled the fire and it enkindled us. Because the pain could no longer be borne, because our anger reached the height of madness, so when news broke about the fire, we couldn’t believe our ears, we even froze for a moment, then we were astonished, then we turned around with caution and the scents of the holy feasts reached our noses, a blazing wind brushed our faces, and we screamed and jumped in the air, we screamed that the fire had become real, had become not impossible, so we threw everything into the fire, we blew on it and it bloomed, we fed it furniture and tree branches and children’s toys and flower bouquets, we carried each other and walked forward bent over, throwing each other into the flames, swaying in joy and raising the sacrifices in the air, we threw in the richest men and the prettiest brides, then we go back and dance the terrible dance of death, we bow down to the hearth and feed it our offspring and some grass, and finally we dream of salvation, we dream of salvation, of the dignity of a single tent in the desert under the light of the moon.

O Diplomacy,

we call on your white gloves, on your prim hat adorned with ostrich feathers, on your starched white shirts and your glossy polished shoes, on your lavish words, on your cold reason. We call on the claims you make out of faith in peace, this peace that yesterday was a just a germ, a hoax, O Diplomacy in ruins.

Don’t come close to our fire, don’t extinguish it, don’t desecrate it. It’s our purgatory––our salvation. The time of hearts whose kindness leads to idiocy is over.

Show yourself to us, O majestic diplomacy,10 show us your face.

See, we’re afraid that beneath the fine veil hanging solemnly over your face we’ll find the face of Golda Meir,

so forgive us, noble lady, for our lack of trust.

- 1. This is, according to the author, the preferred transliteration of her name.

- 2. See Margot Badran (1995 p. 3) and Kifah Hanna (2016 p. 3).

- 3. See Hanan Awad (1983, p. 19).

- 4. For an account of the trial, see Love and Sexuality in Modern Arabic Literature (1994).

- 5. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tI33GNqEyrI&t=946s.

- 6. Baalbaki, 1964, p. 1.

- 7. See Yoav di Capua (2018, p. 126).

- 8. Hanna, 2016, p. 32.

- 9. Kamal Nasser was a Palestinian freedom fighter, poet, editor, and member of the executive committee of the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) who was assassinated by Israeli special forces during a raid on Lebanon on October 10th, 1973.

- 10. It is important to mention that, in Arabic, the word for diplomacy, diblūmāsīyya, is rendered in the feminine; a connection is thus immediately established with the figure of Golda Meir, such that the mocking term “noble lady” refers to both.

Allen, Roger and Hilary Kilpatrick, eds. Love and Sexuality in Modern Arabic Literature. London: Saqi Books, 1994.

Awad, Hanan. Arab Causes in the Fiction of Ghaddah al-Samman, 1961/1975. Sherbook: Editions Naaman, 1983.

ليلى بعلبكي، أنا أحيا، بيروت: المكتب التجاري، 1964.

ليلى بعلبكي، "حضرت ولادة الفجر"، "على وجه الماء مشى حبيبي" و"أيتها الدبلوماسية: نارنا لا تطفئيها"، الأدب 21، رقم 11-12 (1973): 28-29. https://al-adab.com/sites/default/files/aladab_1973_v21_11-12_0028_0029.pdf

ليلى بعلبكي، سفينة حنان إلى القمر، بيروت: المكتب التجاري، 1966.

Badran, Margot. Feminists, Islam, and Nation: Gender and the Making of Modern Egypt. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

Di Capua, Yoav. No Exit: Arab Existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Decolonization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

قناة الغد، "رواية «أنا أحيا» للكاتبة اللبنانية ليلي بعلبكي"، يوتوب، 19 تشرين الاول 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tI33GNqEyrI&t=946s

Hanna, Kifah. Feminism and Avant-Garde Aesthetics in the Levantine Novel. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2016.