Another Camp or The Second Testament on Camp

theoc1_copy.jpg

melting lovers

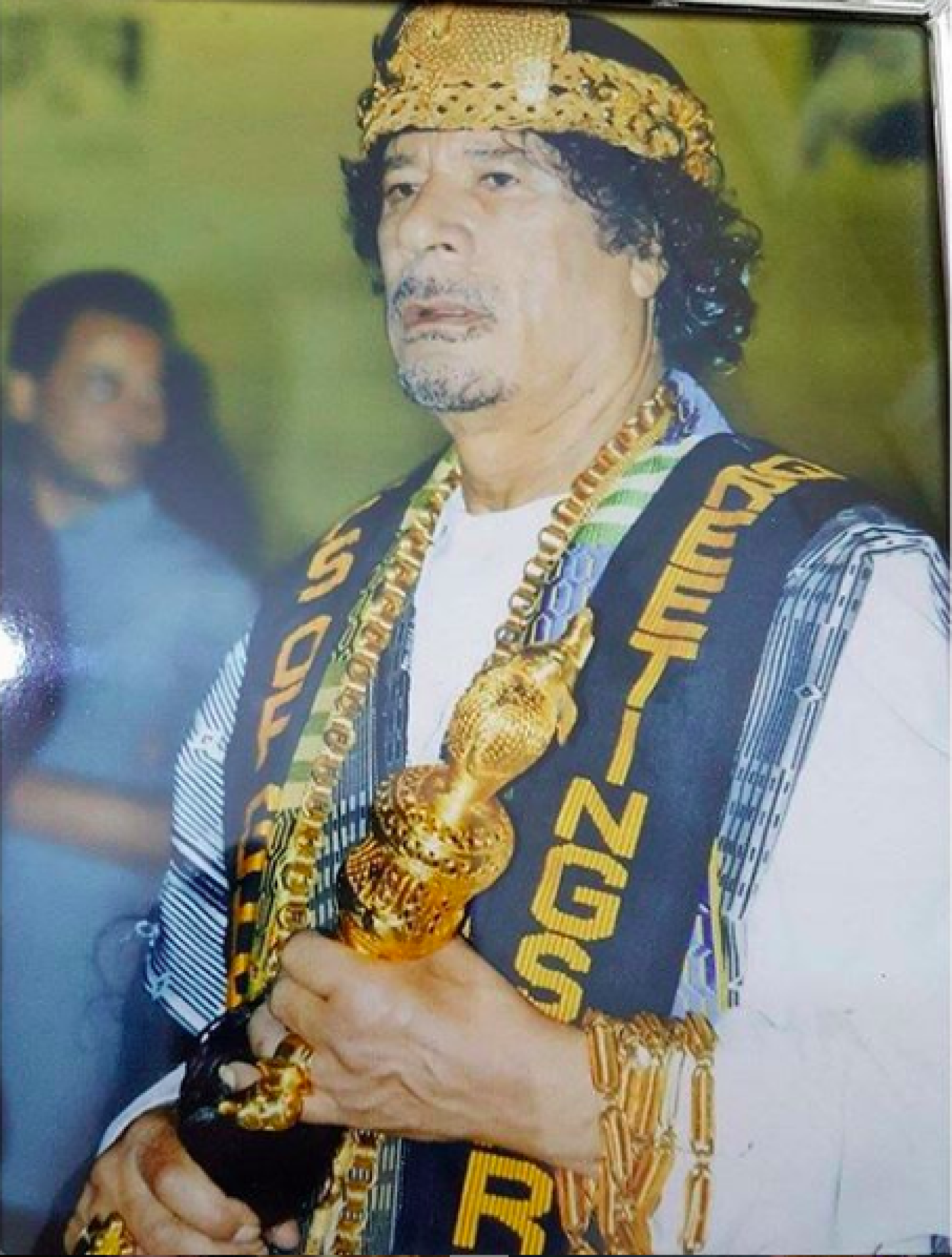

Arab camp is excessive, is subversive, is emancipatory, is visceral. Arab camp is queer and kitschy; it is at once naïve, self-conscious, and reflexive. Arab camp is self-Orientalisation, it is belly dance outfits worn by Khansa1 or The Darvish2. Arab camp is golden framed mirrors hung on velvet textured wallpapers in the bathroom. It is so much terter3, face coverings, and bustiers. Arab camp is textures, and bright clashing colors, it is knockoff Gucci T-shirts sold on sidewalks in downtown where lining the street mannequins clad in costumeish lingerie watch. It is high fashion: Ahmed Serour, Trashy Clothing, and Kojak, but it’s also popular culture: Fifi Abdu, She’ban Abd El Reheim, and Ismail Yassine. It is somehow at once both Gadhafi, a military dictator with an eccentric wardrobe and the blossoming drag scene in Beirut; both distinct from the canonical Western kinds of camp, but also othered to each other, unequal in their affluence.

“49. The relation between boredom and Camp taste cannot be overestimated. Camp taste is by its nature possible only in affluent societies, in societies or circles capable of experiencing the psychopathology of affluence.”

“49. The relation between boredom and Camp taste cannot be overestimated. Camp taste is by its nature possible only in affluent societies, in societies or circles capable of experiencing the psychopathology of affluence.”

This point that Susan Sontag makes is in her 1964 essay “Notes on Camp” is my main point of divergence from her text. She only adequately captures the spirit of one kind of camp, the kind that she reads as legible. However, all camp is not equal. The Sun King in his opulent halls, and his brother Prince Philippe in drag are not like Marsha P. Johnson or the eighties ballroom scene in New York. Similarly, one cannot compare Gadhafi crowned, decked out in regalia, gold scepter in hand, to the drag queens of Beirut, performing between riots and demonstrations (illustrated by artqueerhabibi). The question emerging here is one of power, one of class.

This point that Susan Sontag makes is in her 1964 essay “Notes on Camp” is my main point of divergence from her text. She only adequately captures the spirit of one kind of camp, the kind that she reads as legible. However, all camp is not equal. The Sun King in his opulent halls, and his brother Prince Philippe in drag are not like Marsha P. Johnson or the eighties ballroom scene in New York. Similarly, one cannot compare Gadhafi crowned, decked out in regalia, gold scepter in hand, to the drag queens of Beirut, performing between riots and demonstrations (illustrated by artqueerhabibi). The question emerging here is one of power, one of class.

The ruling elite can inhabit the world in modes that are off-limits to their subjects, but this has not stopped those who societies sought to snuff out from ultimately becoming the makers of taste, across the world. Understanding “the good taste of bad taste" and becoming the “aristocrats of taste” was the means by which the outcasts of society triumphed and ultimately came to fashion the world. The dominance of elite culture is constantly under the threat popular culture proposes. By inhabiting the world in a mode alternative, popular culture counters the supremacy of the elite by its very nature. This hegemony of taste is a constant grapple between those who own the means of cultural production, and those who would dictate the market of cultural consumption. Thus the creators of counter-culture, be them drag queens, designers, or filmmakers, are also at once activists, resisting hegemony in their very existence but moreso in their creativity. Stuart Hall argues that the dominant tradition “suspects that they are about to be overtaken by what Bakhtin calls the ‘carnivalesque’.” Arab Camp, in its outcry against the hegemony of good taste evokes and embodies the imagery of Bakhtin’s carnivalesque, and riots in its existence against “good taste” (Hall 1993). Through observing camp in a variety of fields in contemporary Arabic-speaking countries, I want to embark on a visual journey to explore the forms that this Other camp takes.

History and Terms

The 1964 essay “Notes on Camp” (Sontag, 1964), the bible of the sensibility, the most seminal text written on the subject, guided me on my journey through the canonical history of camp. Camp is French in its origin, coming from the phrase se camper, which is to pose, and from the palace city Versailles built by Louis XIV. It had a long way to go from its grandiose nativity in Versailles. Camp travelled from Versailles’ glittering courts in northern France, to the dandies in the bustling streets of London’s high society; there, it came upon its ultimate devotee, Oscar Wilde. With the death of Wilde, camp made the transatlantic traverse; it travelled down the Hudson, rioted in Manhattan4, and had a ball in Harlem5. Nearly thirty years from Jenny Livingston’s documentary Paris is Burning, on the first Monday of May 2019, camp threw a gala in its own honor in the star-studded halls of the Metropolitan Museum.

The aforementioned odyssey of camp only explored the term’s life within the Western canon. One might assume from this that camp is historically situated within that canon, and belongs exclusively to it. How, then, to explain my familiarity with camp outside of these Western contexts, which only as I traced its histories I was uncovering? It would be radical to resituate camp, and suggest that perhaps by other names, it was blooming outside of its Western history. However, having lived it, seen it, consumed it, met it, worn it, and conversed with it, I am certain that camp has been inhabiting spaces outside of its canon. Sontag’s essay documents the history of Camp through only one of its dimensions, and though it was written as an introduction to Camp, it is regarded by many as the end-all text on the subject. In examining the alternative dimensions of Camp I interrogate this assumption and propose that Sontag’s essay was only the first testament to the sensibility, and not in fact the end-all text.

The notion of an Arab Camp is not so easily captured; the terms at our disposal are ill suited, at once not enough to capture the spirit of excess and too quick to essentialize the region and its aesthetics in an imperialist tradition. The term camp, elusive as it may be, is nowhere near as packed as the term Arab. Wars have been fought, and borders drawn all according to diverging understandings of the word. That is not to mention the racism that black people and ethnic groups such as the Kurds, the Amazigh, the Berbers have endured, as well as the forced Arabization which sought to assimilate their cultures and erase their own rich histories and cultures. In using the term Arab throughout this text, to describe the “other” kind of camp I witness, I acknowledge that I am contributing to this erasure and discursive violence. However, I use the term as a self-identifying Arab because it is what I can speak as.

Cinema

Egypt, in regard to cinema, is often referred to as the Hollywood of the region. With some of the very first production houses, and as the largest hub of cultural production, Egyptian cinema was broadcast into the homes of every Arabic-speaking household. There is a tradition of crossdressing in Egyptian comedy that stands to be analyzed. It is crucial to deconstruct these representations of crossdressing to understand the hidden obsession with what we might call drag – an obsession that is rooted in, but goes beyond, the colonial concept of heteronormativity or gender, beyond state controlled modes of performance, and biopower, beyond controlling how society is reproduced. There is a space on the margins that has continuously intrigued, even if it has only been explored under the guises of irony and comedy. What differentiates between crossdressing and drag? Were Ismail Yassine, and Mohamed Henedy, in drag? Though Judith Butler of course would argue that all we do, be it in our assigned genders or not, is drag, where does that leave intentional drag performers? Ru Paul famously claims “we are all born naked, and the rest is just drag” echoing Butler, but still leaving the distinction between drag and every day performances of gender, that subvert or conform to it, unmade. Not all Camp is naïve; drag queens camp knowingly. In that sense, this kind of Camp must be intentional, must be a theatricalization where one participates knowingly. Therefore, there are inherent differences between these depictions of men cross-dressing in women’s clothing and drag, the first of which is ambition, and the second, intention.

Would a cross-dresser be a drag-queen if they would remain within the confines of the gender they choose to cross? A drag queen parodies the gender she depicts through her moves, her dress, and her make-up. This communal enjoyment of subversion, of excess, and of performance that cannot be contained in binaries is artifice; it is a celebratory one. This celebration of excess and the burgeoning overflow that would resist any confines is not present in our crossdressing protagonists with the same ambition as in the drag scene.

Another difference is rooted in intention. If we were to consider the excess in comedic crossdressing we must also consider what it is parodying. It is a parody of women and not of womanhood or of gender. Crossdressing is a performance of femininity which satirizes women; it is sexist. Drag is a performance of femininity which satirizes gender performance, femininity, and the construction of the gender binary. It calls into question what a woman is, unlike the patriarchal depictions of men acting as women which seeks to dictate to the audience what a woman is. Crossdressing in comedy perpetuates the gender binary, and in making femininity the butt of the joke, is often misogynistic. Drag, on the other hand, is subversive; by calling into question the gender binary it ultimately carries emancipatory undertones. Despite its complicity in sexism, the crossdressing in Egyptian cinema does still have the “failed seriousness” that makes it camp, the dramatized posing and posturing, the artifice.

Another difference is rooted in intention. If we were to consider the excess in comedic crossdressing we must also consider what it is parodying. It is a parody of women and not of womanhood or of gender. Crossdressing is a performance of femininity which satirizes women; it is sexist. Drag is a performance of femininity which satirizes gender performance, femininity, and the construction of the gender binary. It calls into question what a woman is, unlike the patriarchal depictions of men acting as women which seeks to dictate to the audience what a woman is. Crossdressing in comedy perpetuates the gender binary, and in making femininity the butt of the joke, is often misogynistic. Drag, on the other hand, is subversive; by calling into question the gender binary it ultimately carries emancipatory undertones. Despite its complicity in sexism, the crossdressing in Egyptian cinema does still have the “failed seriousness” that makes it camp, the dramatized posing and posturing, the artifice.

These aforementioned differences are made explicit through the contrast between the above photos of Ibrahim Nasr as Zakeya Zakareya and Ismail Yassine preparing for his role as Anissa Hanafi. The limp wrist, smeared lipstick, and disheveled hair, are all embodiments of failed womanhood; even the weight and size of Nasr’s Zakeya calls to attention her inability to conform to the confines of proper womanhood, as dictated by the patriarchy. However, these accentuations of excess make failed womanhood the subject of ridicule, rather than ridiculing the delineations of gendering existence to begin with. On the other hand, Anissa Hanafi transgresses the confines of gender, and embodies excess and contradiction, satirizing the rigidity of the binary rather than making a joke of femininity. However, both are examples of excessiveness and artifice, and therefore examples of camp.

These aforementioned differences are made explicit through the contrast between the above photos of Ibrahim Nasr as Zakeya Zakareya and Ismail Yassine preparing for his role as Anissa Hanafi. The limp wrist, smeared lipstick, and disheveled hair, are all embodiments of failed womanhood; even the weight and size of Nasr’s Zakeya calls to attention her inability to conform to the confines of proper womanhood, as dictated by the patriarchy. However, these accentuations of excess make failed womanhood the subject of ridicule, rather than ridiculing the delineations of gendering existence to begin with. On the other hand, Anissa Hanafi transgresses the confines of gender, and embodies excess and contradiction, satirizing the rigidity of the binary rather than making a joke of femininity. However, both are examples of excessiveness and artifice, and therefore examples of camp.

Drag

Anya Kneez, Zuhal, Anissakrana, Diva, Melanie Coxxx, Hoedy Saad, Latiza Bombe, Glammzy, Andrea, Demetria Corset, Robin Hoes, and Emma Gration are only a few of the drag queens transforming Beirut nightlife. Their performances include Voguing, lip-sync, comedy, and incredible costumes and dancing. Voguing, rooted in excess, in posing, camp to its very core, returns to the term its original French meaning. What makes fashion paramount to drag culture, particularly excessive, comedic, ironic, and exaggerated expressions of it, is what makes it camp. Each of these queens has their own flavor and specialty, but all of them are animating what is becoming a vibrant and pulsating drag scene that rivals any worldwide. Drag, in its foregrounding of artifice and its celebration of excess, is in its nature camp.

“I think camp is an aesthetic that ridicules the rules of what makes something beautiful! It highlights the ugly or the weird factor in something and makes it the new beautiful! It’s ironic. It’s a statement, saying that something is soo ugly that it makes it beautiful. It changed a lot of things in art because now beauty of an artwork doesn’t matter as long as it triggers you somehow! It could be cheesy, feminine, lame, outrageous, flamboyant and it would be seen as normal, cuz its camp. Where do I see it? In the Lebanese drag scene for example. The over exaggerated outfits with cheesy characters, the outrageously ironic performances!”

“I think camp is an aesthetic that ridicules the rules of what makes something beautiful! It highlights the ugly or the weird factor in something and makes it the new beautiful! It’s ironic. It’s a statement, saying that something is soo ugly that it makes it beautiful. It changed a lot of things in art because now beauty of an artwork doesn’t matter as long as it triggers you somehow! It could be cheesy, feminine, lame, outrageous, flamboyant and it would be seen as normal, cuz its camp. Where do I see it? In the Lebanese drag scene for example. The over exaggerated outfits with cheesy characters, the outrageously ironic performances!”

Anissakrana, Lebanese Drag Artist.

Arab drag has entangled roots, affected by the ball scene in Harlem, contemporary Western pop-culture such as RuPaul’s Drag Race, but also following in a local tradition. It is not an imported or Westernized practice, but a fusion of local as well as Western influences.

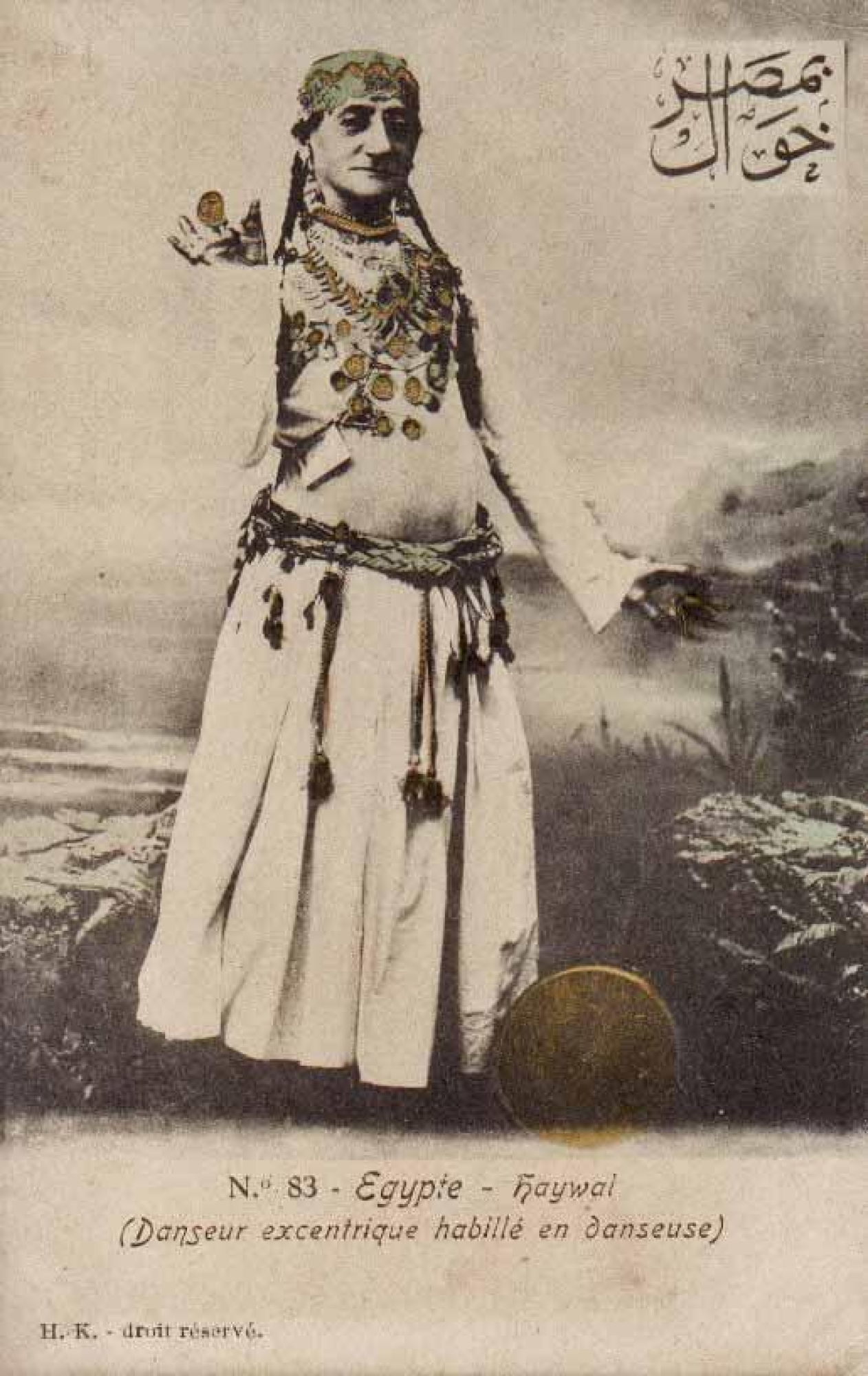

Drag was also flowering in an eighteenth century Middle East. Belly dancing became an increasingly censored practice, especially for women, and in response to these limitations the field became welcoming to a fresh variety of male performers. The men performing would dress in silks, braid their hair, and tattoo their bodies in Henna, dressing for the role. However, more intriguing than their emulation of the femininity in belly dancing was their fusion of this with their own masculinity. They were not attempting to pass as women, oftentimes combining men and women’s clothing when dancing and embodying a seductive sexual ambiguity. Rather, they were introducing an entirely new and tantalizing combination of gender performances, queering the more rigid gender norms of their Western audiences, and acceding the expectations of regional viewers. These male belly dancers in drag were known as Khawal, a term that has since taken on a dark meaning, and is used as a derogation of queer Arab people.

Drag was also flowering in an eighteenth century Middle East. Belly dancing became an increasingly censored practice, especially for women, and in response to these limitations the field became welcoming to a fresh variety of male performers. The men performing would dress in silks, braid their hair, and tattoo their bodies in Henna, dressing for the role. However, more intriguing than their emulation of the femininity in belly dancing was their fusion of this with their own masculinity. They were not attempting to pass as women, oftentimes combining men and women’s clothing when dancing and embodying a seductive sexual ambiguity. Rather, they were introducing an entirely new and tantalizing combination of gender performances, queering the more rigid gender norms of their Western audiences, and acceding the expectations of regional viewers. These male belly dancers in drag were known as Khawal, a term that has since taken on a dark meaning, and is used as a derogation of queer Arab people.

The Orient has acted as the imaginary space, where fantasies of desire and fear can be projected at once, where all cultures coalesce and become one since Ingres painted Grand Odalisque and Gerome The Snake Charmer. With the rigid frigidity of Victorian sexuality, the Orient became a place to imagine sex differently, fetishize its excess, variations, and even its lack. Images of the oversexed harem, colors, fabrics, jewels, spices, makeup, and dancing overwhelmed the understanding of non-white culture for years, though it ultimately had more to do with the drug fueled collective hallucinations of Europe, and then Hollywood, than with anything truly happening in any “other” place. Thus, self-Orientalizing plays into this imaginary. However, it draws on actual existing histories, and foregrounds the agency and creativity of the Other performing it. Self-Orientalizing, in its assertion of the agency of the Other, references Homi K. Bhabha’s theories of mimicry (Bhabha 1994). Essentially Bhabha argues that when the colonized adopts the culture of the colonizer, but not quite perfectly, this is mimicry. This practice juxtaposes the aesthetics imposed on the colonized, in this case the Orientalized Other, with their own aesthetics. The performer of mimicry is at once embracing, reclaiming, and resituating these aesthetics, and subverting the power of the colonizer in their initial imposition. This subversion contains the radical potential of unsettling the established power dynamic. The intentionality of playing into a trope brings to it a celebratory color, and allows it to be reclaimed by those which it once dominated.

Fashion

“I grew up in a culture where we fall into the stereotypical description of what a woman or man is “supposed” to be which is not always okay. At the same time, I am loyal to how I was raised-the idea that the woman and the man are two separate worlds. On the other hand, my idea of gender is that everyone is whatever they feel they are, however you may call it. So I guess in my work I naturally include all those things and not be closed just in one ideology. Camp is a way of performance, style and some say life. I guess the image I have is that of drag and very very creative outfits.”

“I grew up in a culture where we fall into the stereotypical description of what a woman or man is “supposed” to be which is not always okay. At the same time, I am loyal to how I was raised-the idea that the woman and the man are two separate worlds. On the other hand, my idea of gender is that everyone is whatever they feel they are, however you may call it. So I guess in my work I naturally include all those things and not be closed just in one ideology. Camp is a way of performance, style and some say life. I guess the image I have is that of drag and very very creative outfits.”

Sarah Bougsiaa, Libyan designer, photographer and creative living in Barcelona

Designers like Kojak, Shukri Lawrence, Omar Braika and Ahmed Serour have been amassing cultural capital, and gaining online popularity. With their influencer models, they are redefining contemporary style, and fashioning the elite throughout Arabic-speaking countries. In dominating everything from streetwear to high fashion, these designers are inadvertently saturating the local fashion industry with queer aesthetics. However, in the region on a social and political level, people with nonconforming sexualities or gender performances are met with violence and issues of gender and sexuality are continuously being met with vitriol. As a result of the class of ruling elites giving their children imported educations, a whole generation of Egyptian twenty-somethings are far more acquainted with, if not accepting of, liberal ideologies, including the liberal tolerance towards queer people and issues. With the deterioration of economies across the region, these people who at one point could afford wardrobes of brand-name imported garments, can no longer do so and have had to make lifestyle adjustments. Though they are far from a majority, these classes are precisely the clientele of high fashion in the region. To fill this demand, local and regional couture brands have become more popular and fashionable. Brands like Okhtein, Jude Benhalim, and Elie Saab are all fast gaining international attention and status. Fast catching up with them are designers like Kojak and Ahmed Serour, whose designs are quirkier and more provocative. My personal favorites of the bunch are Shukri Lawrence and Omar Braika, the creative duo behind Trashy Clothing. Their clothing juxtaposes the aesthetics of different classes, mixes colors and fabrics, challenges gender performances, and radically bridges high and low culture. All of this to say that their aesthetics are an Other camp. The contradictions of globalization, class, and gender all are manifest in their work, and the result of all of these tensions sewn together is Camp.

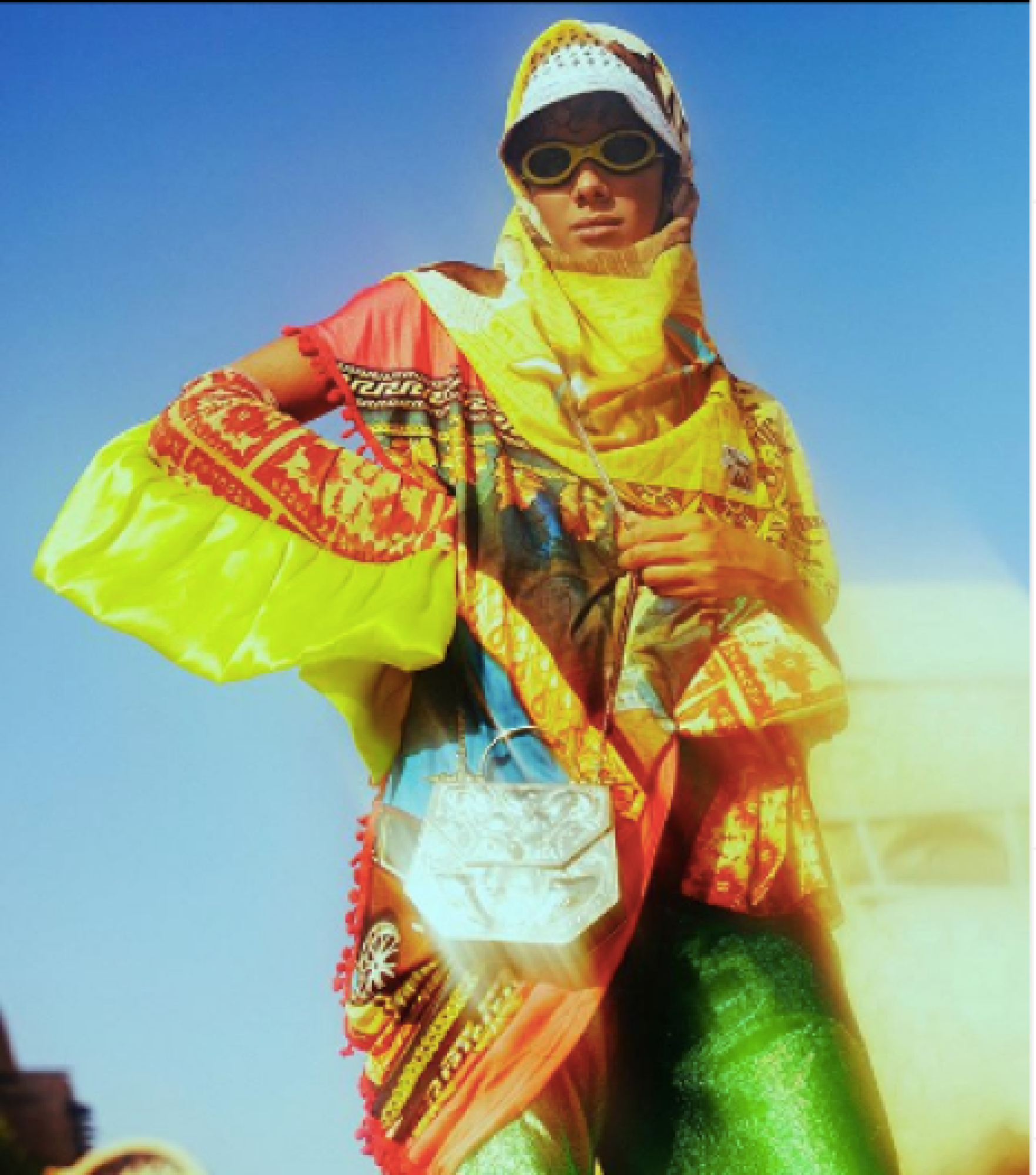

This photo is of an Okhtein bag styled by Ahmed Serour with Ahmed Serour pants and gloves. The fabrics are yellow, red, and glittery green, some patterned and some solid. Loose and flowy they are styled with an ornate geometric metal silver purse, against the soft blue backdrop of clear sky. The photo showcases a lot of tension in the colors, structures, and material used. The woman wears a veil over her hat, manifesting excess. The whole shoot is filtered through a dreamy lens with foggy backgrounds and soft lighting, which lends it the feel of a fantasy or hallucination. The glasses feel like an outdated cyberpunk or an old imaginary of futuristic style (Blade Runner), or a kitschy addition that clashes with the oriental rural cuts of the fabric. The top, with its dangling embellishments and yellow sleeve frills, feels feminine, but also channels a very rural Egyptian aesthetic (falaha) that is charged with negative connotations in the cultural imaginary. In contrasting these elements with the high fashion Okhtein purse and high budget shoot, Serour contributes to the bridging of high and low culture, an exercise in camp.

This photo is of an Okhtein bag styled by Ahmed Serour with Ahmed Serour pants and gloves. The fabrics are yellow, red, and glittery green, some patterned and some solid. Loose and flowy they are styled with an ornate geometric metal silver purse, against the soft blue backdrop of clear sky. The photo showcases a lot of tension in the colors, structures, and material used. The woman wears a veil over her hat, manifesting excess. The whole shoot is filtered through a dreamy lens with foggy backgrounds and soft lighting, which lends it the feel of a fantasy or hallucination. The glasses feel like an outdated cyberpunk or an old imaginary of futuristic style (Blade Runner), or a kitschy addition that clashes with the oriental rural cuts of the fabric. The top, with its dangling embellishments and yellow sleeve frills, feels feminine, but also channels a very rural Egyptian aesthetic (falaha) that is charged with negative connotations in the cultural imaginary. In contrasting these elements with the high fashion Okhtein purse and high budget shoot, Serour contributes to the bridging of high and low culture, an exercise in camp.

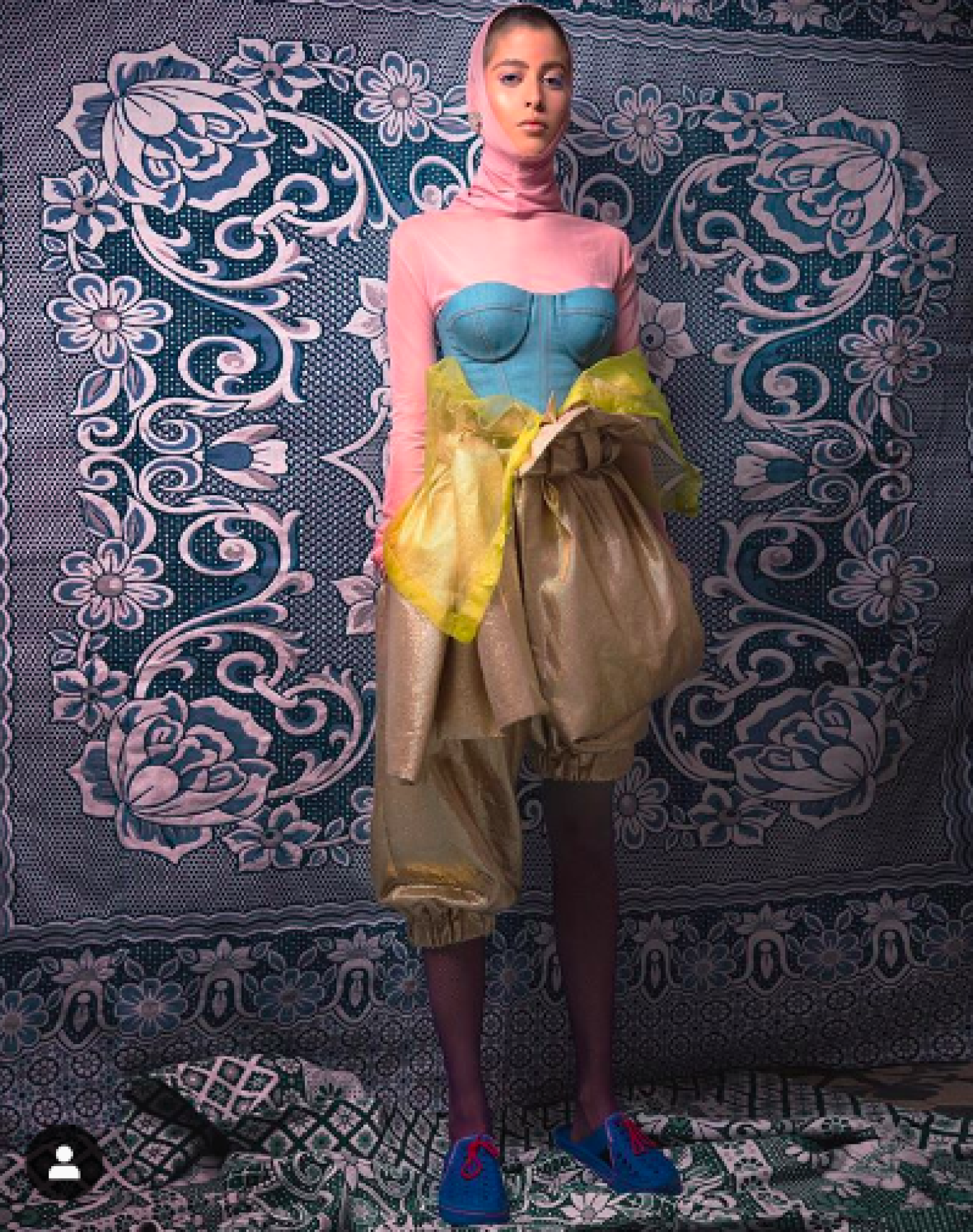

This photo is of a Kojak corset, and an Ahmed Serour mesh top and pants styled by Ahmed Serour. The backdrop is an Egyptian duvet, coverta, present in most households but still a signifier of a lower class. The look feels like a deconstructed homage to the 18th century French portrait of Louis XIV, which is in itself a very camp reference. The gold harem pants styled with tights and crocs feels simultaneously opulent and cheap. The blue denim corset, layered with a pink mesh top, contrasts with the dark blue rubber of the shoes and the fabric of the backdrop. The yellow tulle literally burgeoning from the pants adds to this portrait of excess. The pink veil is styled to blend in with the mesh top, or perhaps is a part of the top, and the only part of the model not draped in fabric is her face. The clash of fabrics and aesthetics in this photo is also what makes it so camp. It unapologetically makes references to what is culturally understood as “bad taste.”

This photo is of a Kojak corset, and an Ahmed Serour mesh top and pants styled by Ahmed Serour. The backdrop is an Egyptian duvet, coverta, present in most households but still a signifier of a lower class. The look feels like a deconstructed homage to the 18th century French portrait of Louis XIV, which is in itself a very camp reference. The gold harem pants styled with tights and crocs feels simultaneously opulent and cheap. The blue denim corset, layered with a pink mesh top, contrasts with the dark blue rubber of the shoes and the fabric of the backdrop. The yellow tulle literally burgeoning from the pants adds to this portrait of excess. The pink veil is styled to blend in with the mesh top, or perhaps is a part of the top, and the only part of the model not draped in fabric is her face. The clash of fabrics and aesthetics in this photo is also what makes it so camp. It unapologetically makes references to what is culturally understood as “bad taste.”

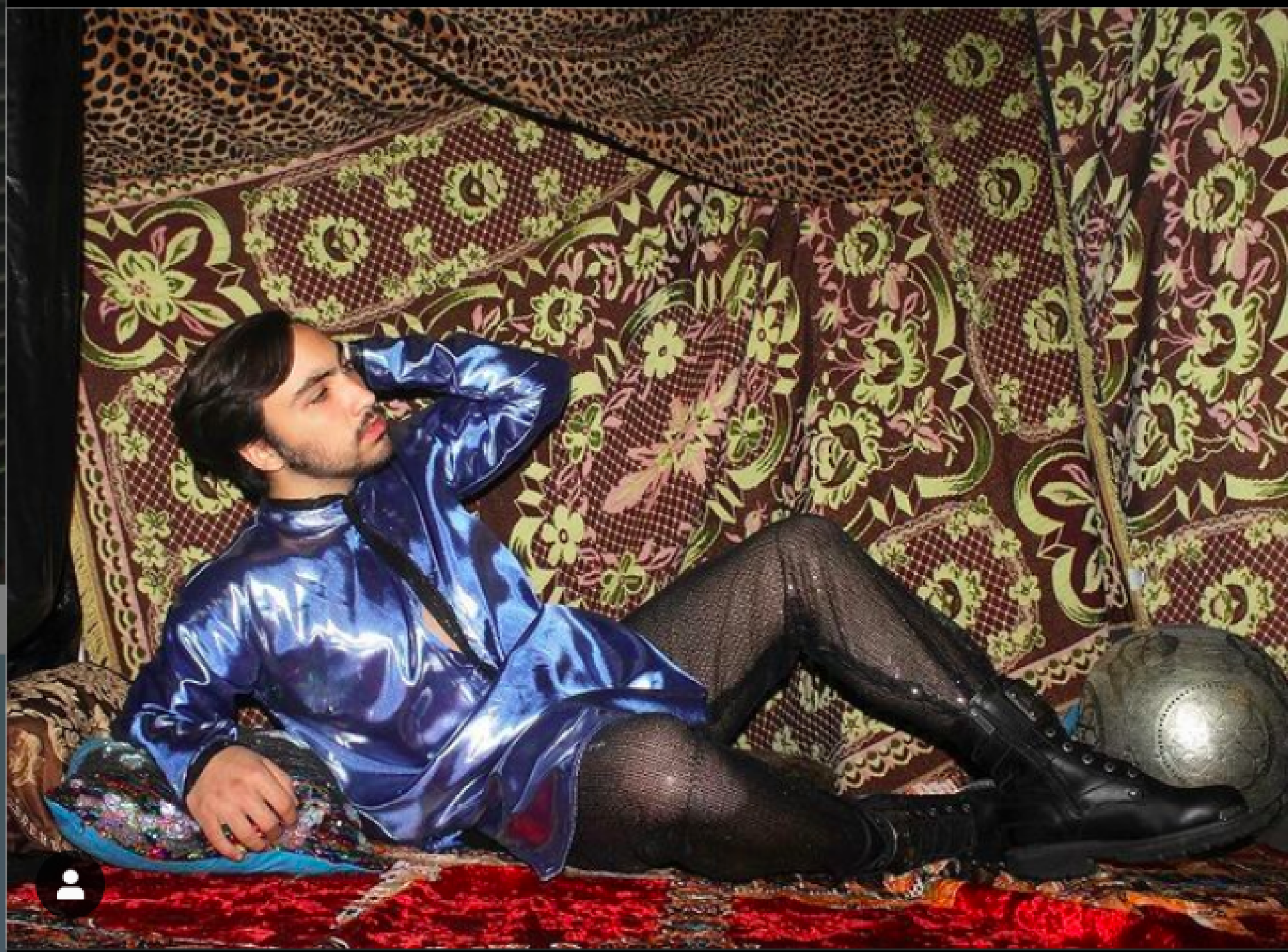

Designer brand Trashy Clothing, has received critical acclaim from Vogue, GQ, and a handful of reputable fashion magazines. The co-creatives behind the concept are Palestinian Shukri Lawrence and Omar Braika. A self-described “satirical, campy, political, and queer RTW Palestinian fashion brand that breaks stereotypes put upon the Middle East and provokes bigotry through fashion. Founded by Shukri Lawrence in 2017, the tRASHY goal is to reclaim the Arab and Palestinian Identity and reclaim what is considered different, cheap, and trashy in modern culture.” The image across is from a 2018 Instagram post. The backdrop is an “ethnic” bed covering and draws on images from the everyday kitsch of popular culture, clashing with the turquoise pillow the model leans on, embroidered with terter, channeling and resituating signifiers of bad taste. The cut of the top is similar to a sleek galabeya. However, rather than the modest and unassuming colors one is used to seeing on this garment, it is a lustrous and gleaming electric blue. Paired with sheer loose fitting fishnet tights, this top imbues the entire outfit with feminine signifiers. Lastly the posturing of the model references Orientalist nude paintings such as Grand Odalisque by Ingres.

Designer brand Trashy Clothing, has received critical acclaim from Vogue, GQ, and a handful of reputable fashion magazines. The co-creatives behind the concept are Palestinian Shukri Lawrence and Omar Braika. A self-described “satirical, campy, political, and queer RTW Palestinian fashion brand that breaks stereotypes put upon the Middle East and provokes bigotry through fashion. Founded by Shukri Lawrence in 2017, the tRASHY goal is to reclaim the Arab and Palestinian Identity and reclaim what is considered different, cheap, and trashy in modern culture.” The image across is from a 2018 Instagram post. The backdrop is an “ethnic” bed covering and draws on images from the everyday kitsch of popular culture, clashing with the turquoise pillow the model leans on, embroidered with terter, channeling and resituating signifiers of bad taste. The cut of the top is similar to a sleek galabeya. However, rather than the modest and unassuming colors one is used to seeing on this garment, it is a lustrous and gleaming electric blue. Paired with sheer loose fitting fishnet tights, this top imbues the entire outfit with feminine signifiers. Lastly the posturing of the model references Orientalist nude paintings such as Grand Odalisque by Ingres.

This is a photograph by Mous Lamrabat, a Moroccan-Belgian photographer. He juxtaposes the preconceived notions associated with the burka with the unexpected gold color and cinched waist. The gold belt, rings, and headpiece contrast with the dress as they accentuate the face and makeup, which contradicts the conservative associations we have of the burka. The gold, with its wrinkled fabric, also feels at once royal and cheap. The setting, presumably a supermarket, sets the drinks aisle as the backdrop for the photo, the harsh florescent lighting does not flatter the dress but rather clashes with it. The blue plastic bag that the woman holds contrasts with the gold of the dress. Her placement in the supermarket paired with her shiny clothing feels eerie and otherworldly, like Lamrabat embraced the idea of the alien, both as alienated but also as extraterrestrial, and infused his photo with that quality. It challenges notions of religiosity, and highlights a facet of absurdity in globalization through excess.

This is a photograph by Mous Lamrabat, a Moroccan-Belgian photographer. He juxtaposes the preconceived notions associated with the burka with the unexpected gold color and cinched waist. The gold belt, rings, and headpiece contrast with the dress as they accentuate the face and makeup, which contradicts the conservative associations we have of the burka. The gold, with its wrinkled fabric, also feels at once royal and cheap. The setting, presumably a supermarket, sets the drinks aisle as the backdrop for the photo, the harsh florescent lighting does not flatter the dress but rather clashes with it. The blue plastic bag that the woman holds contrasts with the gold of the dress. Her placement in the supermarket paired with her shiny clothing feels eerie and otherworldly, like Lamrabat embraced the idea of the alien, both as alienated but also as extraterrestrial, and infused his photo with that quality. It challenges notions of religiosity, and highlights a facet of absurdity in globalization through excess.

This photo is from Kojak’s collection “Daddy’s Dolls”, and is styled by Aya Negm. The photo has a similar dreamlike quality to the previous one. Foregrounded in the photo is the model’s gloved hand. The jumpsuit and gloves as well as the backdrop are all covered in pink and purple glitter or sequins. The jumpsuit itself, an homage to 80s VHS at home workout videos, is a shiny teal lined with pink and purple streaks. The model has styled long hair, and a groomed mustache and beard, channeling an ambiance of French royalty. The combination of features typically reads as masculine with an ultra-femme background, and the outfit reads as a world of over the top candy fantasy, ultimately camp.

This photo is from Kojak’s collection “Daddy’s Dolls”, and is styled by Aya Negm. The photo has a similar dreamlike quality to the previous one. Foregrounded in the photo is the model’s gloved hand. The jumpsuit and gloves as well as the backdrop are all covered in pink and purple glitter or sequins. The jumpsuit itself, an homage to 80s VHS at home workout videos, is a shiny teal lined with pink and purple streaks. The model has styled long hair, and a groomed mustache and beard, channeling an ambiance of French royalty. The combination of features typically reads as masculine with an ultra-femme background, and the outfit reads as a world of over the top candy fantasy, ultimately camp.

This photo is a frame from Khansa’s music video “Khabberni Keef,” an explosion of orientalist imagery and erotic energy. This frame is the closing shot of the video. Khansa sits in the middle, flanked by two masked figures that represent the kinky subculture of BDSM in their attire. He lays in the lap of an old woman, seemingly a witch, who throughout the video is torturing him with her magic. The photo’s soft dramatic lighting feels like a Baroque painting and the composition of the photo makes reference to the Orientalist movement of Gerome and Ingres. The frame features a lot of red that contrasts with the neutral colors and the black background, giving the photo a surreptitious depth and foregrounding the figures at the center, while hiding the rest in shadow. The references made in the photo as well as the melodramatic posing of Khansa and the figures around him saturate this frame in camp.

This photo is a frame from Khansa’s music video “Khabberni Keef,” an explosion of orientalist imagery and erotic energy. This frame is the closing shot of the video. Khansa sits in the middle, flanked by two masked figures that represent the kinky subculture of BDSM in their attire. He lays in the lap of an old woman, seemingly a witch, who throughout the video is torturing him with her magic. The photo’s soft dramatic lighting feels like a Baroque painting and the composition of the photo makes reference to the Orientalist movement of Gerome and Ingres. The frame features a lot of red that contrasts with the neutral colors and the black background, giving the photo a surreptitious depth and foregrounding the figures at the center, while hiding the rest in shadow. The references made in the photo as well as the melodramatic posing of Khansa and the figures around him saturate this frame in camp.

Pop Culture

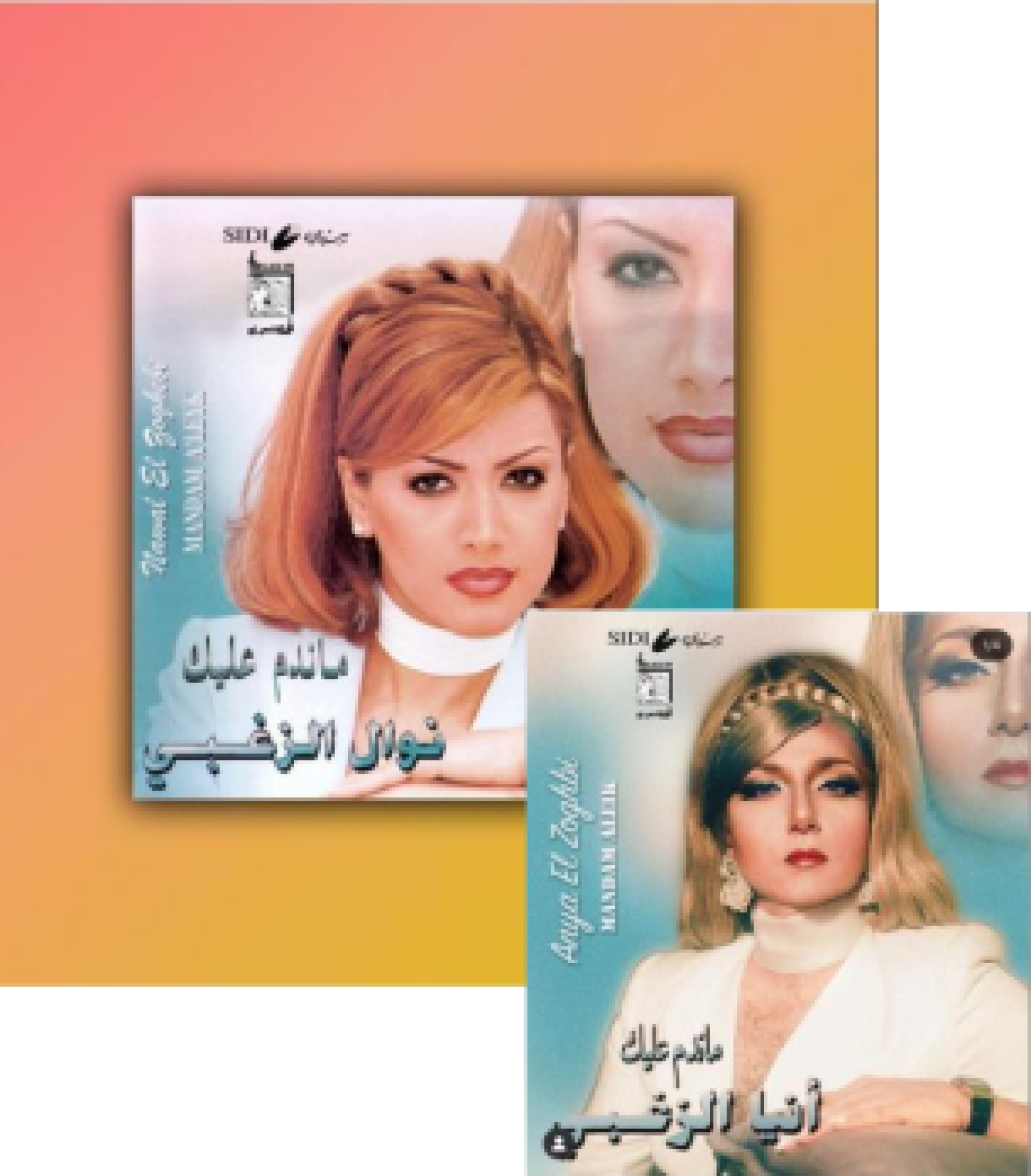

Icon of excess, drag queen Anya Knees, is a Lebanese drag queen living in New York. Her looks are influenced by retro Arab pop stars and 80s American disco aesthetics. She channels Nawal Al Zoghby and Cher flawlessly, and creates looks that speak to the aesthetics of the Arab diaspora or globalized Arab at once obsessed with the imported 80s culture they grew up with and their own kitschy pop icons.

Icon of excess, drag queen Anya Knees, is a Lebanese drag queen living in New York. Her looks are influenced by retro Arab pop stars and 80s American disco aesthetics. She channels Nawal Al Zoghby and Cher flawlessly, and creates looks that speak to the aesthetics of the Arab diaspora or globalized Arab at once obsessed with the imported 80s culture they grew up with and their own kitschy pop icons.

Zuhal, Lebanese drag queen and part of the legendary HAUS OF EGO, makes reference in her drag to a much older regional tradition of candelabra dancing. In the 1920s, Badia Masabni, renowned Egyptian belly dancer, performed with a candelabra on her head as a show of skill and prowess. This dancing was also made famous by the renowned Tahia Carioca. Though Zuhal dons a much more minimal candelabra, it is a recognizable reference to this tradition. Despite the minimalism that makes her outfit sleek and modern, the makeup, and candelabra on her head are signifiers of excess.

Zuhal, Lebanese drag queen and part of the legendary HAUS OF EGO, makes reference in her drag to a much older regional tradition of candelabra dancing. In the 1920s, Badia Masabni, renowned Egyptian belly dancer, performed with a candelabra on her head as a show of skill and prowess. This dancing was also made famous by the renowned Tahia Carioca. Though Zuhal dons a much more minimal candelabra, it is a recognizable reference to this tradition. Despite the minimalism that makes her outfit sleek and modern, the makeup, and candelabra on her head are signifiers of excess. Edward Said penned “Homage to a Belly-Dancer” (Said 1990), which he wrote for Tahia Carioca; in it, he recounts his experience in watching her dance, and describes her dress and movement, saying “The beauty of her dance was its connectedness: the feeling she communicated of a spectacularly lithe and well-shaped body undulating through a complex but decorative series of encumbrances made up of gauzes, veils, necklaces, strings of gold and silver chains, which her movements animated deliberately and at times almost theoretically. She would stand, for example, and slowly begin to move her right hip, which would in turn activate her silver leggings, and the beads draped over the right side of her waist.” Zuhal, in channeling this icon, deliberately references all the seductive and Oriental signifiers from Carioca; it is a testament to the resistance to the Western gaze, and the uplifting of Arab heritage.

Edward Said penned “Homage to a Belly-Dancer” (Said 1990), which he wrote for Tahia Carioca; in it, he recounts his experience in watching her dance, and describes her dress and movement, saying “The beauty of her dance was its connectedness: the feeling she communicated of a spectacularly lithe and well-shaped body undulating through a complex but decorative series of encumbrances made up of gauzes, veils, necklaces, strings of gold and silver chains, which her movements animated deliberately and at times almost theoretically. She would stand, for example, and slowly begin to move her right hip, which would in turn activate her silver leggings, and the beads draped over the right side of her waist.” Zuhal, in channeling this icon, deliberately references all the seductive and Oriental signifiers from Carioca; it is a testament to the resistance to the Western gaze, and the uplifting of Arab heritage.

These references are unique to the cultures that Anya, Masreya, and Zuhal come from, and are overt tributes of excessiveness to icons of excess from their lived experience. Hand painted women towering over text, posing dramatically, or kitschy Photoshop edits, or candelabra resting like a crown on a queen’s head all come together to perform the drama of what Arab camp was and has become. Grounded in pop culture, but also in queer joy, these images all embody those concepts and balance them out with a note of seriousness. These are not parodies but rather homages.

These references are unique to the cultures that Anya, Masreya, and Zuhal come from, and are overt tributes of excessiveness to icons of excess from their lived experience. Hand painted women towering over text, posing dramatically, or kitschy Photoshop edits, or candelabra resting like a crown on a queen’s head all come together to perform the drama of what Arab camp was and has become. Grounded in pop culture, but also in queer joy, these images all embody those concepts and balance them out with a note of seriousness. These are not parodies but rather homages.

Conclusion

This paper was born in Beirut amidst the throngs of a revolution, and comrades of anti-colonial thought. The overwhelming feeling that I wanted to convey throughout this text was that of queer innovation, creation, and ultimately, joy. Throughout Arab cinema, fashion, drag, and pop culture, so many examples of camp emerge. It would be amiss and negligent to erase this richness of cultural production with the broad strokes of Western academia. Sontag’s assertion that camp is only possible in affluent societies after this journey feels completely false and insignificant. Truly, in examining the historical and contemporary examples of camp throughout the culture, it feels undeniable. The tangibleness of the Other camp is at once loud and indisputable. The joy in documenting these few examples of the Other camp has been validating and left me feeling a connectedness with my own heritage and cultural production.

- 1. A Lebanese singer and belly-dancer

- 2. A Syrian belly-dancer in diaspora

- 3. A kind of glitter used in embroidery

- 4. Stonewall, 1969.

- 5. House-ballroom community, made popular in 1980s New York, USA (origins tracing back all the way to the 1920s) where African-American and Latin-American queer people assembled, performed and created communities on the margins.

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

Hall, S. (1993). "What Is This ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?" Social Justice 20(1-2): 104-114.

Said, E. (1990). Homage to a Belly-Dancer. London: London Review of Books.

Sontag, S. (1964). Notes on Camp. New York City: Partisan Review.