zohra; or how i learnt to love and write the body

theod1_copy.jpg

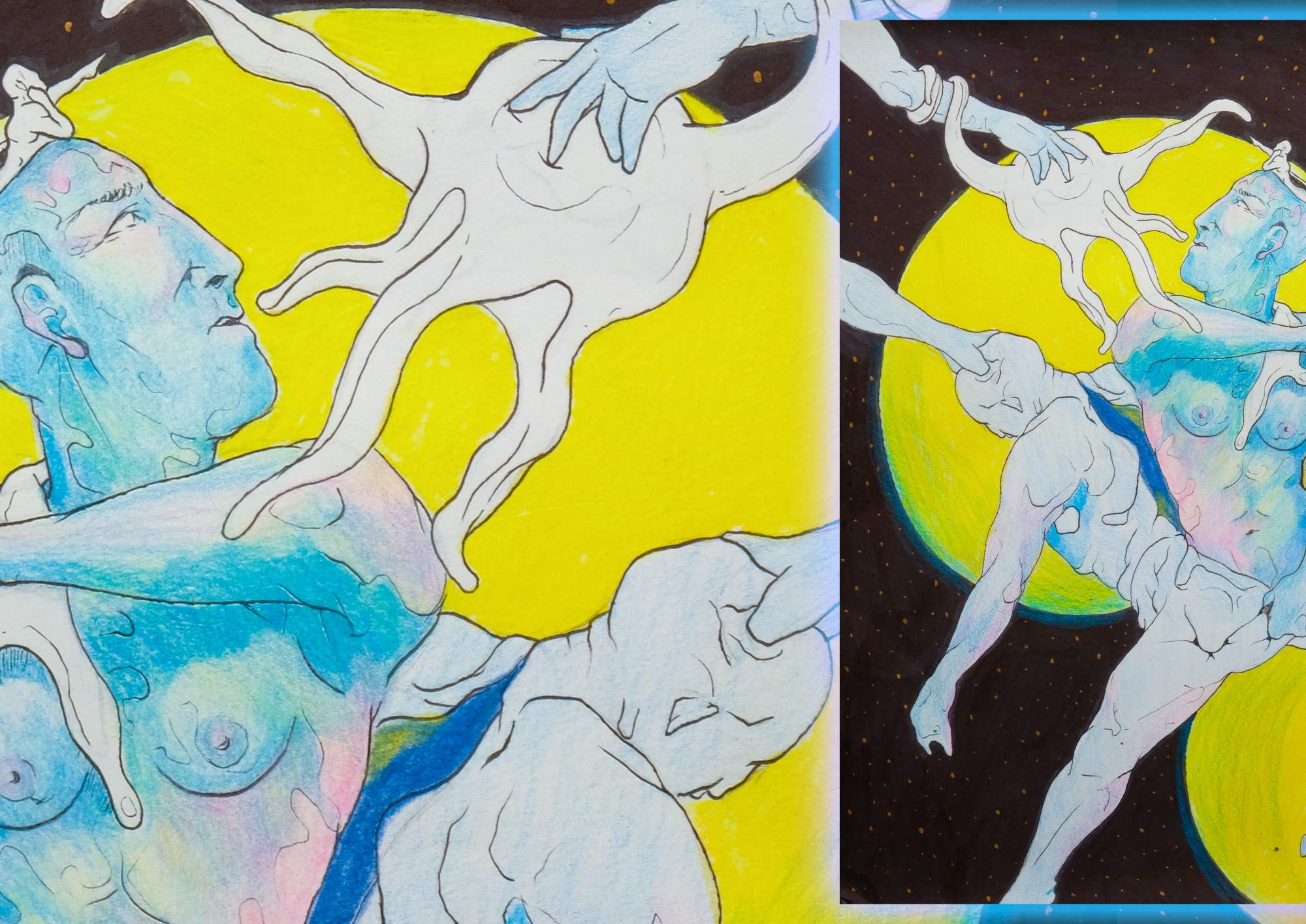

star shedding its skin

She always takes out the Quran from her room before she comes. It isn’t her room exactly. Her mother prays there sometimes because of the quiet. She has often lain there, covered in her bedspread despite the heat, her mother praying in the corner. Her father sits outside on his computer chatting with younger women and no one ever talks about it. She has stopped taking the Quran out. I am not sure what sex means for any of them. What do we think about when we orgasm alone? All of us, in our rooms, always alone, coming to a lit screen, our faces blue in the light. I sometimes make a point of wiping my fingers on the walls of my room. I am not sure why. It makes me feel brave.

“When my face is flushed with blood, it becomes red and obscene.”1

[an old american woman once asked me if there was a war going on in pakistan when i told her where i was from] What does being queer mean in my native language which I can no longer remember? [she said i was beautiful] My friend’s name is Zohra and we meet often. She likes girls too but we never talk about it; she’s always on about dildos and how she’s found a website and fantasizes having a box full of dildos being shipped to her. I’d offer her a fist or a limb but we love in other lonely ways.

[this is a poem]

*

I have never felt the need for another body. But there is such incredible want that I can no longer touch the tips of my fingers together. Zohra and I see each other sometimes. She likes to drag her nails down the length of my arm and I sit looking at her. She sometimes wears the hijab and tells me how cool this TV show is that I’ve never heard of. We talk in English when we’re alone. I have never been naked in front of anyone.

I have lived my life in a silent conversation with bodies I imagine. I am never certain if what I desire is flesh or its language, I have no language I can want in, my desire is not my own, without the word, is the tightening of my throat even real. Zohra speaks fluent Urdu, for her wanting is legible, the taste of an elbow has a word. But I exist between languages, my desire is something I’ve made up in foreign words and silences. When I press my thumb against your cheek I can simply breathe.

There are no words for us in Urdu. We still use the word دوست for each other when with others, but between ourselves language always fails. Every sentence to each other begins with the word “suno” (listen).

*

When Zohra was 17, she got her nose pierced and came out to her college friends. Nobody took her seriously, and she later fell in love with a boy on the internet. “I wish we were real lesbians and the girls in Mrs. Anjum’s class would give us hell so I could have a reason to beat the shit out of them.” Zohra likes the way my forehead arches and says that it’s a sign of good luck.

In school you would get punished if you walked around holding hands. She would hold me by the elbow, her fingers moving against the inside of my arm under my sleeve. I would sometimes move her hand to my hair and she would pretend to braid them as she would run her fingers around the shape of my head. She once found a mole above my left temple but didn’t know what it meant.

[My neck is warm under the palm of your hand, but your mind is elsewhere]

In college my best friend once fingered someone in the stalls. And we are lying here, your fingers in my hair and I imagine what it would feel like to orgasm as a boy on a charpayi with a flower in my hair. “ہے loneliness عجیب” We never say much, I am never sure what to say, so I put my palm on your stomach instead.

*

Knowing and loving my body has always been a lonely affair. As a finger traces the outline of a curve, a vein, an opening, I try to love past the excess of myself, the excess of blood and flesh and nerve, the abjection of it all, the strange silent horror of the body. “I have never gotten used to my period,” Zohra once mentioned casually, curled up in my bed, a pillow between her legs. “It always blows my mind, how much I can bleed, how much I carry within me, how I still haven’t died of it.”

Zohra loves to run her hands through the hair on my legs, smoothing it down, and sticking it back up again. She says it calms her. Younger, I once decided to stop shaving because I felt dirty afterwards, as if I had betrayed myself by caving into the shame. Refusing to shave and letting the hair grow became a way to feel closest to the body I wish I had on some days, a different body, another body, with more hair and less flesh, one which would make me a man and be wanted by other men, by Zohra, by the in-between space she inhabits, to be wanted by her/him/them, all of Zohra, every part of Zohra, the man, the woman, the days when Zohra was neither, barely just flesh. The body isn’t enough, yet it’s too much, it’s…

Loving her is lonely too. That night among our friends when you asked me to dance with you and I suddenly felt too small in my oversized clothes. I just stood and watched you move. Now in the dark I try to imagine your outline, your weight next to me, your hair thinning as you age and wear out, as I’m wearing out too. [“How do we still go on?”] You danced with the boys in crop tops, hairy chests exposed, necklaces heavy across collarbones, glitter on eyelids. “See you don’t have to be gay AND miserable,” one of the boys said, swaying his hips to a foreign song. “Suno…” I began. “Suno….” “Suno….”

*

“Where will we go,” he asks, “when everything finally ends.” Our knees touch as our legs dangle from the pier, a snake-charmer looking up at us from the sand below. Our friends are loud next to us, laughing at how camp Rani Mukherji is, reciting ghazals to each other, tea cups passing back and forth between them. [These are the people that I have been promised. They are not mine. I lose them all the time]. Zohra had taken off her shoes earlier and jumped down on the sand, saying she wanted to collect sea shells to take back home. I can feel him breathe next to me, my shawl on his shoulders, the smudged red on his mouth. He looks wistfully at one of our friends, another boy in a bright red kurta, hunched laughing over his phone. I try not to envy the ease with which they laugh together, unmindful of the stares, their hair a mess of blue and purple, fingers intertwined. We tell each other things nobody else knows, stories of secret flings, heartbreaks, abortions, check-ups. Someone suggests we write down all the hurtful words, the slurs and insults, the names people have called us throughout our lives; they say that by writing them down we can maybe reclaim them, make them hurt a little less. So, we do that, passing leaves of paper around, laughing nervously, asking each other what a certain word meant, who used it, when. If anything hurts less afterwards, no one really says.

Sitting with them, sometimes I feel none of them are real. The girl wearing her brother’s kurta, saying nothing else feels right on her body; the boy with a crop of green hair who wants to get another piercing—I didn’t think they could be real, could exist, not here. Sometimes I feel as if I made them up in my head.

“I feel calm next to you,” he says. Now when I feel small in my clothes, I blame the sea.

*

Zohra has trouble sleeping, lying next to me she keeps sighing. I suggest we go upstairs. On the roof, she walks away from me and puts on a surgical mask. [I keep losing you] I breathe through my dupatta and feel you come up behind me, resting your head on my back. Your arms dangle. I can’t find a moon but there is light. [I am not unhappy] The city isn’t remarkable but there is an unusual amount of abandoned construction sites. Perhaps all cities have them. “We could live here,” you pointed to a tower once, a would-have-been shopping mall, and I think about that every time I pass it on the way to work. It would always be this way.

My phone vibrates, someone wants to hook up, we text till he comes. You didn’t feel like meeting today. I am awake in this city. Outside, a gun goes off for no reason. On Instagram someone’s posted a photo of themselves in my scarf they had borrowed. Double tap. A fierce queen, I comment, and prayer hands, prayer hands, prayer hands.

*

They will all move away when the city finally runs out of air. The ones with money will find careers abroad, some will marry and have secret Grindr and Tinder accounts, some will remain home to see what happens after the air goes. “I can’t leave,” I tell Zohra during one of her last visits. She doesn’t want to argue, she says, but she wishes I tried harder. [i told the old american woman it wasn’t so bad in pakistan, it was like everywhere else, and she believed me] Elsewhere is not a place. [Where will we go?] It had always been lonely loving them, I’d like to tell them, but never hard. Zohra, all of her, all of them, so many of them, never made love difficult. Perhaps because they understood that silence wasn’t an absence, that this could be it, this could be enough, that it could be simple, that it was okay. I try to picture Zohra, her face blue from her phone, texting me a meme from across the room, the way her voice would get when something moved her, the way she would unconsciously cup herself with a strange expression on her face. [The more I write them, the more I forget a little every day] I go on. The boys in Karachi are still there on the beach, copulating into an indistinguishable mass, trying desperately to will something different into existence.

[I keep losing you] We drove in the storm as the city collapsed around us [Where will we go when all of this is over] I said I’d remember you forever [when all of this is over] We are not unhappy, it doesn’t matter [when all of this is over] It was always okay [when all of this]

سنو سنو سنو سنو سنو

[this is just a poem]

*

- 1. Taken from Georges Bataille’s Solar Anus.