Paris Is Burning: Intersectionality, Localization, and Circulation in France

This paper is an adapted and edited English version of the book chapter “Intersectionnalité” in: Dorlin, Elsa. (Ed.). 2021. Feu ! Abécédaire des féminismes présents. Paris: Libertalia, 319-336.

A second version of the book chapter was published in French as part of: Noël, Fania. 2022. Et maintenant le pouvoir. Un horizon politique afroféministe. Paris: Cambourakis.

_72a9440_600dpi1.jpg

Les Femmes D'Alger, 2012

Since its emergence in the French context, academics and activists have clashed over the definition of “intersectionality,” but also intramurally within those spaces where questions of legitimate forms of knowledge remain a point of contention. In this paper, I will map the paradoxical circulation of intersectionality by focusing on how the concept participated in the shaping of both alliances and antagonisms amongst and between activist organizations, academia, mainstream political groups, and the French State. This same intersectionality, which has given birth to significant intellectual channels of debate among scholars, feminists, and anti-racist activists (but also between scholars and activists), is nevertheless presented as a homogeneous and unified object. There exists another paradox: anti-racist and leftist political activists criticize intersectionality, arguing that it can be co-opted by neoliberalism or femonationalism. Yet the reality is that the reconfiguration of reactionary discourses in France has recoded intersectionality to mean “Islamist fundamentalism/racialism/anti-universality.”

My role as an Afro-feminist activist and the founder of a non-academic political journal on intersectionality has afforded me an exceptional vantage point as an agent of and witness to ideological debates and confrontations around intersectionality in France since the early 2000’s among activists, scholars, and politicians. It has also allowed me to employ auto-ethnographical methods, supported by my notes and personal archives gathered over 13 years of activism in France. In early 2021, in the midst of the new moral panic in France around the idea of “separatism,” “anti-republicanism,” and “wokeness,” the popular [far] right magazine L’Express published an article titled “Indigènes, NPA, Mwasi: Searching for the Patient Zero of Self-Segregated Meetings for People of Color.” The journalist concludes that I was the so-called patient zero, due to my involvement in different political groups. While the article was clearly racist, it is true that I have been a political actor in contemporary French anti-racist/Black political organizing and that, along with others, I have helped shape the current public debate concerning anti-racist organizations, the State, and the media. Deeply inspired by the work of bell hooks, Christina Sharpe, Joy James, Saidiya Hartman, and Patricia Hills Collins, I am choosing to use the “we” in some parts of this article as a statement on ethics and accountability. My experience as an activist in those movements has led me to this research, helping me to formulate questions and hypotheses, while gathering information and accessing several keys actors. Also, given my involvement in the planning and organizing of several mobilizations, political groups, activist campaigns, and statements analyzed here, I believe it is important not to distance myself from these choices and from my former and current political comrades. It is also essential to highlight the production of theories and ideology which occurs outside of academia. As a former activist, I am well aware of the pitfalls of becoming a native informant and the possible application of my work toward the exclusion and subjectivation of Black people. The use of “we” reflects my commitment and aspiration as a Black feminist scholar to embody what Toni Morrison (in Greenfield-Sanders 2019) described as follows: “I don’t want to speak about Black people, I want to speak amongst them.” Black Studies and Black feminist sociology – fields in which my work is deeply anchored – are pushing boundaries and destabilizing academia in productive ways, by reframing the notion of the so-called neutral voice and by acknowledging positionality as an integral part of research and site of knowledge. While going beyond the personal/theoretical dichotomy, this standpoint understands the distinction that bell hooks drew between private and confessional practices:

Using the private to transgress the public, to disrupt and subvert, does not take place solely by the practice of confession. This is why people critique confession. Private life as exhibitionism and performance is not the same thing as a politicized strategic use of private information that seeks to subvert the politics of domination. (hooks and McKinnon 1996, 823)

Tragic News Story

“Theo’s changed a lot since he started hanging out with his girlfriend” (Poingt 2021).

This quote was highlighted in a March 1, 2021 article published in Le Figaro (a French daily newspaper), following a fateful incident that led to the murder of a 15-year-old girl in the department of Val d’Oise. The two suspects, of the same age as the victim, were Theo and his girlfriend Junie. The article described Theo, a white and young teenager, as being “super shy,” “very polite,” “not even 50kg,” and overly influenced by his girlfriend, Junie, who is a Black girl of Haitian descent.

Whereas images of the two teenagers represented in mainstream media and on social networks prompted the typical statements of condemnation and indignation, the gendered and racialized comments concerning the physique of the female suspect (stocky, intimidating), contrasted with Theo’s, caught my attention. The article in Le Figaro is a prime illustration, as it condenses and mobilizes a lexical field closely mirroring that used in juvenile courts for girls (Vuattoux 2021). The media and juvenile courts generally categorize girls involved in crimes or misdemeanors as being targets of manipulation (Cardi 2007).1 However, in this particular case, gender stereotypes operated differently, centering on descriptions of her influence and maturity compared to Theo’s innocence. The framework used to make the crime legible borrows from sexist and racist imaginaries of almost demonic temptresses bringing out the vilest instincts from within the recesses of innocent whiteness. This treatment is a product of the imbrication of racist, patriarchal, and classist imaginaries in a particular socio-historical context. Intersectionality is an important tool for understanding the complexity of these situations.

In the United States, “intersectionality” as a concept of critical race theory has formalized analyses and practices already present in Black feminist movements. These movements have produced their own vocabulary to analyze the articulation of oppressions (Taylor 2017) as evidenced by the Combahee River Collective’s crafting of the term “identity politics.”

2005 – A Pivotal Year

In France, the 2005 translation of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s “Mapping the Margins”2 (Crenshaw and Bonis 2005) in an academic journal marks the concept’s official earth-shattering entry into both intellectual and activist spaces. Both of those spaces were in the midst of deep reexamination, in a context of almost total divide between academia and non-white activist circles. This hermeticity makes it difficult to “decarcerate” (or extirpate) concepts from academic spaces for use in activist struggles. Exporting such concepts has provoked legitimacy clashes between academics and those activists who operate outside the university and in adjacent spheres.

To understand how this concept circulated through movements led by French women descended from postcolonial immigration,3 one must first grasp the evolution (Abdallah 2002) of anti-racist activism in France. Indeed, it was women from anti-racist circles who would later launch organizations that utilized intersectionality as an analytical tool.

After the 1983 March for Equality, discourses produced by anti-racist movements were firmly anchored in issues around legal status (nationality, asylum, immigration law). At the end of the 1990s, the growing presence of French citizens with origins in postcolonial immigration led to a paradigm shift in anti-racist discourse in France. For these populations, their main ties were no longer with the country of origin but with a France that had birthed these new generations. This shift has led to the questioning of the framework imposed by the political left (which governed the majority of municipalities populated by immigrant groups) and a rejection of the idea that class is the primary dimension of struggle. Groups such as the Mouvement de l’Immigration et des Banlieues4 (Movement of Immigrants and Banlieue Residents) founded in 1993 and active until 2006 (Taharount 2019) articulated a political critique of class reductionism within the left. Their ideological position can be seen as the political translation of reclaiming a form of racial autonomy.

In the early 2000s, a number of new anti-racist organizations emerged in the wake of several controversies. During the first public debates surrounding the 2004 law prohibiting religious symbols in schools, organizations such as Mamans Toutes Égales (Mothers All Equal) already highlighted the racist and sexist facets of the law. The largescale revolts of 2005, sparked by the deaths of Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré, marked a rise in the number and reach of anti-racist organizations that defined themselves as banlieusard-e-s, autonomous, and deterritorialized. These new organizations (Voix des Roms [Voice of the Roma], Brigade Anti-Negrophobie [Brigade Against Anti-Blackness], Parti des Indigènes de la République [Party of the Republic’s Indigenous Peoples5], Les Indivisibles [The Indivisibles]...) which took strong and unequivocal stances on race, were founded and led by Blacks, Arabs, or Asians who were mostly upwardly-mobile French nationals. These organizations were composed primarily of people from working-class neighborhoods and higher education backgrounds; these activists’ patterns of socialization gave them access to concepts studied and forged within the university. A critical approach to race, often articulated alongside class, was at the heart of these organizations’ analysis and organizing. At the same time, women in these organizations produced analyses of gendered racialization and the weaponization of immigrant women’s living conditions in working-class neighborhoods for racist purposes. The racialization of crimes such as gang rapes (Hamel 2003) in neighborhoods composed mainly of working-class residents from postcolonial immigrant backgrounds offers a particularly salient illustration of this form of racism that operates under an ostensibly anti-sexist banner.

The Chokehold: Primary Struggles vs. Secondary Struggles

In France, compared to anti-racist movements, Black, Arab, or Muslim feminism triggers much less opposition from political figures and the media, provided it espouses narratives of liberation from inherently barbaric and patriarchal immigrant communities. The Ni pute, Ni soumise (Neither Whore nor Submissive) – a movement launched in 2003 by Fadela Amara following the murder of Sohane Benziane6 – contributed to the legitimizing of sexism in the banlieue as a social problem. It also received both state funding and extensive media coverage (Dalibert 2013; Guénif-Souilamas 2006; Guénif-Souilamas and Macé 2004). Feminisms stemming from postcolonial immigration were able to establish their autonomy vis-à-vis mainstream feminist organizations (at this time, it was essentially impossible to simultaneously articulate anti-sexist, anti-racist, and class analyses) by clarifying their positions regarding the State, which they identify as racist, sexist, neoliberal, and a primary facilitator of the domination they endure as racialized7 women. In their first statements, feminists speaking from these margins had to manage a constant back-and-forth between, on the one hand, defending themselves from critiques accusing them of allowing their anti-sexism to be instrumentalized by white feminism, racist conservatives, and liberal political parties, and, on the other hand, dealing with the injunctions to stand in solidarity with men from their communities.

The most media-visible organization, Ni pute, Ni soumise, crystallized the antagonism between different feminist currents fostered by women with origins in former French colonies. The “Appel des Féministes Indigènes” (The Indigenous Feminists’ Call to Action) of 2007 broke with the feminist divide, simultaneously opposing anti-sexism and anti-racism, as at the time they were seen, for different reasons, as antithetical (by State feminism and anti-racist organizations):

We refuse to serve as a battleground between subaltern and dominant patriarchies. Therefore, we stand firm in a paradoxical feminism where we’ll never again serve as white supremacy’s Trojan horse or traitors to community principles. (Collectif Féministes Indigènes 2007)

It is no surprise that the precursors of this positioning were lesbian feminists born of postcolonial immigration. In 1999, the Groupe du 6 novembre (November 6th Group) was launched as “a collective of lesbians whose history is linked to slavery, colonization and imperialism; or ‘lesbians of color,’ as we’re known in Anglophone countries.” In 2001, this group detailed its political positioning and use of intersectionality as an analytical tool (Groupe du 6 novembre 2021). Its first publication, derided by mainstream lesbian groups, “used an intersectionality lens to critique racism in feminist and LGBT circles” (Provitola 2019). One can assume that ongoing trans-national exchanges and dialogue within lesbian circles nourished the November 6th Group’s socialization around conceptual tools used by “lesbians of color” across the Atlantic.

In 2005, Lesbiennes of color (LOCs), a collective that aimed to be a “space of possibilities, of encounters, and of struggle” (Amaouche 2015) was born. In 2015, political scientist and activist Fatima Ouassak spearheaded the launching of the Classe, Genre, Race (Class, Gender, Race) network. Its mission was to serve as a “reference point to understand and organize against discriminations targeting women descended from postcolonial immigration” (Réseau Classe/Genre/Race 2015), with a clear goal of shaping public policy.

Establishing the anti-racist movement’s independence vis-à-vis the left and expanding it beyond issues affecting the banlieues allowed for a remapping of battlegrounds, establishing race as a frontline struggle alongside class by analyzing and mobilizing around issues of racial division within the proletariat (police violence, employment and education discrimination, substandard housing). But this shift also introduced an implicit strategic posture: for those anti-racist groups (emerging directly post-2005 and focusing exclusively on racism, unlike groups like LOCs, which came a few years later), patriarchal domination remained a secondary political struggle.

This stance from anti-racist/decolonial organizations was justified by a constant emphasis on the undeniably racist instrumentalization of anti-sexism in France in a political climate where neoliberal white feminism and far-right islamophobic agendas converged. For many of these anti-racist groups, postcolonial immigrant feminism was suspected to be inevitably co-opted by the State and racist discourse, and the feminist stance was useful when limited to an anti-femonationalist (Farris 2017) politics. The space for political action based on a critique of patriarchy was limited to two positions that aimed to escape potential co-optation: silence or the expression of solidarity. We see here how the movement is deployed paradoxically, as women of color describing themselves as feminist were only welcome if they could be used by anti-racist/decolonial organizations against political opponents to denounce femonationalism and homonationalism.

The socio-political transformations brought about by the Internet disrupted the marginalization and isolation of Afro-feminists (but also non-Black Arab, Muslim, and Asian feminists) within anti-racist organizations, as well as leftist and hegemonic feminist spaces. Social networks and participatory platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and WordPress have played an important role in circulating ideas between political movements and in creating networks with shared political ethics which do not require existing social ties. For the majority of us, intellectual and political socialization around intersectionality occurred via the Internet, through readings and exchanges in these participatory spaces. Afro-feminism appeared around the 2010s, as a legacy of movements such as the Coordination des Femmes Noires (the Coordination of Black Women), a Black-women only group founded in Paris in July 1978 which organized around similar issues; Afro-feminism identified itself in connection to Black feminisms. In this context, intersectionality has emerged as one of the main tools for analyzing and naming oppression. Words are important, but are they the source of struggles? Can we organize and mobilize on the basis of words?

In 2013, along with Naouel and Joao Gabriel, I launched the “INM – Intersectionnalité non-mixte” (People of Color Intersectionality Discussion) group on Facebook. This was a space strictly for non-white people to develop critiques of racism, patriarchy, and capitalism. It was created following our departure from a mixed-race group on intersectionality comprised primarily of white academics. At the root of the discussion group was a textual analysis of a conversation between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde. This analysis suggested that under structural racism, Black (but more largely non-white) women had a duty to be in solidarity with “their” men.8 Decolonial circles reproduced this analysis; it was then co-opted as an anti-racist reading by radical/Marxist white feminists in an unabashed performance of radicalism, as the mainstream feminist movement was at that time very opposed to any analysis of race. When the idea for the AssiégéEs magazine came to me in 2014, contributors to its first issue “l’Étau” (“the vice tightening its grip”) (Collectif AssiégéEs 2015)9 were all members of this Facebook group. AssiégéEs was conceived as a welcoming space for critical reflections difficult to express within anti-racist (due to sexism, homophobia, and transphobia) or mainstream feminist spaces (due to racism, classism, white saviorism, and transphobia). Far from being a movement to be co-opted, the gathering around race, gender/sexual orientation, and class has been crucial to demarcating these spaces from white feminist/LGBT political spaces, not only regarding the question of race, but also class struggle.

Intersectionality Everywhere, Politics (Almost) Nowhere

In 2015, members of the AssiégéEs Collective and the Mwasi Afro-feminist Collective organized the first-ever procession of people of color (POC) in the May Day march. The call for participants was the first political mobilization to explicitly use intersectionality as an analytical tool for collective organizing in France:

Afro-feminists and Racialized Women, Queers and Trans folks condemn the exploitative relationships produced by capitalism as well as the gendered and racialized division of labor.

[...] This is why AssiégéEs and the Mwasi Afro-feminist Collective will march together in Paris on May Day to say loud and clear that there can be no anti-capitalism without a radical fight against state racism and patriarchy. Seriously coming to terms with discrimination and the racist and sexist dimensions of capitalism is of the utmost urgency, even if the ultimate goal is capitalism’s dismantling for the benefit of all.

This system will never be overthrown without those who live on its margins! (AssiégéEs 2015)

In recent years, there has been a proliferation of feminist, queer, and trans groups by and for people of color (QTR, Nta Rajel, Qitoko, Mille et Une Queer, Lallab).10 Initially, we witnessed an explosion of media and political scandals denouncing certain events’ analysis (the Babilou daycare11 (2008), the law on facial concealment in public spaces targeting niqabs (2010), the discourse around the Dominique Strauss-Khan/Nafissatou Diallo sexual assault case12 (2011), the bill aimed at the criminalization of street harassment (2017)). Then a gradual shift saw the antiracism movement, as well as Black, Muslim and decolonial feminist organizing, become themselves direct targets of media and political controversies (the call to end funding to Lallab, the socialist mayor of Paris’ call to ban the Nyansapo festival13 (2016), the decolonial summer camp14). These attacks took aim at race, and the disproportionate weight of discussions about Muslim women led to divisions within feminist organizations. These rifts helped restructure the political tools of certain prominent feminist figures and organizations, regarding their positions on head coverings. The change in the balance of power broadened the scope of the debate; since 2014, debates on intersectionality are no longer confined to activist circles and have taken up media space through the reductive and polarizing framing of “for” and “against” camps (Gramaglia and Le Pennec 2019). These circulation of debates must be understood within a French context marked by a fight for legitimacy around the figure of the public intellectual.15 Before the 2000s – with the exception of a few Caribbean public intellectuals like Aimé and Suzanne Césaire, Maryse Condé, Edouard Glissant – public intellectuals working on racial, gender or class discrimination were mostly white. The year 2000 marked a rise in French Black, Arab, and Asian activists and those adjacent to them (scholars, journalists, artists) aspiring to embody the figure of the public intellectual. For a long time, this demographic was only invited to share and testify their lived experience but not to provide analyses.

The widespread discussion around race/racism in feminist movements led to the spread and centralization of intersectionality, which in turn gave rise to other forms of oversimplification within movements that appropriated the term. Intersectionality alternately appears as a movement, a theory, or a new wave of feminism. A cumulative analysis of oppressions is the most common reading, whereas Kimberlé Crenshaw’s conceptualization relies on articulation. These semantic shifts caused by the concept’s circulation and said circulation’s disassociation of the signifier and the signified transform the term “intersectionality,” which may have brought about a certain depoliticization. Indeed, “intersectional” can come to mean a political identity marker, or even an individual attribute (“an intersectional person”). All that remains, therefore, is an attachment to semantics, to the power of identifying and naming. However, designating this first step toward liberation as the end goal leads to a dead end of the political imagination:

- declarative: to be in opposition to everything is tantamount to having a statement about everything

- performative: centering the process of recognizing privilege as a precondition to organizing or collective action

Over time, [predominantly white] feminist organizations have transformed the term “intersectional” into a synonym for diversity and inclusion. Predominantly white organizations empty intersectionality of its racial dimension and proceed to erase Black women both as the main political subjects of the concept as well as its analysts and theorists. Afro-feminist organizations were the first to distance themselves by heavily relying on the concept of misogynoir (Bailey and Trudy 2018), a concept created by the academic Moira Bailey and the intellectual blogger Trudy to describe the racialized sexism experienced by Black women. The Mwasi Afro-feminist Collective developed a critique of the effects of the concept’s circulation in their book Afrofem, published in 2018:

The fact that white women and predominantly white organizations are laying claim to intersectionality is yet another demonstration of one of anti-Blackness’s motors: steal all the tools we create precisely because this world leaves us nothing. This corruption of intersectionality will reach unprecedented heights: attempted co-optation by animal rights groups wanting to claim intersectionality.

We use intersectionality as an analytical tool, and like any tool, it has advantages (many) and limitations. Intersectionality is a conceptual tool, which was theorized by Kimberlé Crenshaw. She was therefore the first to put a word to the phenomenon: “intersectionality,” pointing to the fact that one can be a target of both racism and sexism, and that these oppressions do not stack like lasagna layers but combine to create a particular form of racism and sexism. As Black women, we speak of misogynoir when discussing our experience of racialized sexism. […] For us, intersectionality is inseparable from race. It is about understanding how racism and patriarchy interact with each other, but also how these systems interact with class, heterocentrism, etc. (Mwasi 2020)

These critiques have also been expressed in the English-speaking world, in texts such as Cameron Glover’s 2017 article “Intersectionality Ain’t for White Women,” or Jennifer C. Nash’s 2019 book Black Feminism Reimagined, After Intersectionality.

Far from the fantasies painted by reactionaries of all stripes, intersectionality is a site of struggles over meaning within feminist, queer, and trans of color organizations in France – struggles that translate into discourses, analyses, and activism.

For some feminist, queer, or trans POC organizations, “intersectionality” conveys the ambition to fight against all forms of oppression simultaneously, within a single organization, as well as to craft hierarchies of domination as an outcome of unending workshops on privilege. Instead of being viewed through their interactions and complexities, individuals trapped in patriarchy-driven systems of domination are seen as static and immutable, and intersectionality becomes a form of magical thinking. These developments create new lines of demarcation, whereby several organizations claim intersectionality as one of many theoretical tools at their disposal and analyze the limits of said tool, while others make it the heart of their political analysis. More broadly, intersectionality is also used to describe cultural projects or productions: intersectional movies, intersectional plays, etc... One example of these border lines is the changing of name of the Queer & Trans, Racisé.e.s (Racialized Queer & Trans) collective to Queer & Trans Révolutionnaires (Queer & Trans Revolutionaries) in 2017. Though the collective remains a group strictly reserved for racialized people, the change of adjective aims to distance itself from other racialized queer groups created during the same period. The collective explicitly highlights its materialist approach:

To be queer is not simply to claim a minority gender and sexual identity, but also to have a militant, revolutionary political positioning against systems of domination (racism, capitalism, heteropatriarchy). (Queer et Trans Révolutionnaire 2017)

While intersectionality became increasingly nuanced, and its misuse/overuse and whitewashing was denounced in Black, Arab, Muslim, and Asian feminist and queer political spaces, it set off a moral panic in the public debate. Political figures and media platforms from the far right to the reactionary left fanned the flames of the panic, pointing to intersectionality as the epitome of the academic threat to the French Republic. The culminating point of this moral panic was a proposed bill on academic research policies.

Academia vs. The Republic

On October 28th, 2020 as the French Senate was discussing a bill on academic research policies, senator Laure Darcos (from the conservative party Les Républicains [The Republicans]) introduced an amendment16 on academic freedom, which required that research be conducted “with respect for the values of the Republic.” For the most part, the amendment, adopted that day, avoids naming these values. On October 31st, more than one hundred academics signed a column in Le Monde (Collective 2020) where they accused humanities scholars of being too closely linked with “racialist and decolonial” ideologies, and thereby being apologetic towards Islamist extremism. The bill and this column arrived a few days after the shocking murder of Samuel Paty, a high school teacher killed by a young man after showing a caricature of the Prophet Mohamed in his classroom. These debates are hardly new; indeed, columns on the same topic have been published, primarily by older white critics, several times in the last ten years, targeting the advocates of critical race theory, postcolonial, and gender and sexuality studies in academia.

The bill’s vagueness provides considerable leeway for authorities to interpret these values and to choose which would-be offenders they want to target. It is not a coincidence, then, that the amendment only mentions laïcité (a form of French secularism) as “first and foremost” among these values. This amendment was proposed only a few days after Education Minister Jean-Michel Blanquer decried in a radio interview the existence of an alleged “Islamo-leftist” presence in universities. He singled out, among others, the UNEF students’ union, accusing it of “intellectual complicity with terrorism.” Prior to this, Blanquer had on several occasions spoken of the “gangrene” of “an intellectual matrix coming from American universities: spreading intersectionality and aiming to essentialize communities and identities,” citing as an example the growing number of symposiums and conferences on race, the French colonial continuum, Afro-feminism, and/or intersectionality. The use of this lexicon in reference to researchers working on race/colonialism (but also on gender and sexuality, as evidenced by some of the column signatories’ criticism of “neo-feminist McCarthyism” in the case of the feminist mobilization against Roman Polanski’s Cesar award)17 has become commonplace. President Emmanuel Macron himself recently accused academia of having “broken the Republic in two” and The New York Times (Smith 2020) of “legitimizing violence” and spreading “lies” through their coverage of race, racism, and the question of Islam in France. When asked by The New York Times if he was not employing the same method as Trump, Macron acted profoundly offended.

This column appeared in a context where racism and specifically Islamophobia (Mohammed 2016) have been on the rise in France, but also where more and more researchers of color can be found producing knowledge and analyses about race and colonial legacies in France (Larcher 2015), both within academia and public spaces. The column signatories supported Prime Minister Jean Castex’s claims that apologists for Islamist extremism are lurking among scholars, and that being “made to feel remorseful for colonization” is a recipe for terrorism. This debate is part of a long history of accusations that the humanities as a discipline makes excuses for individual behavior. We can find the same lexicon in columns from the 1980s criticizing Bourdieu’s work on reproduction and symbolic violence. Sociologists studying crime, drugs, or even terrorism have also come under attack.

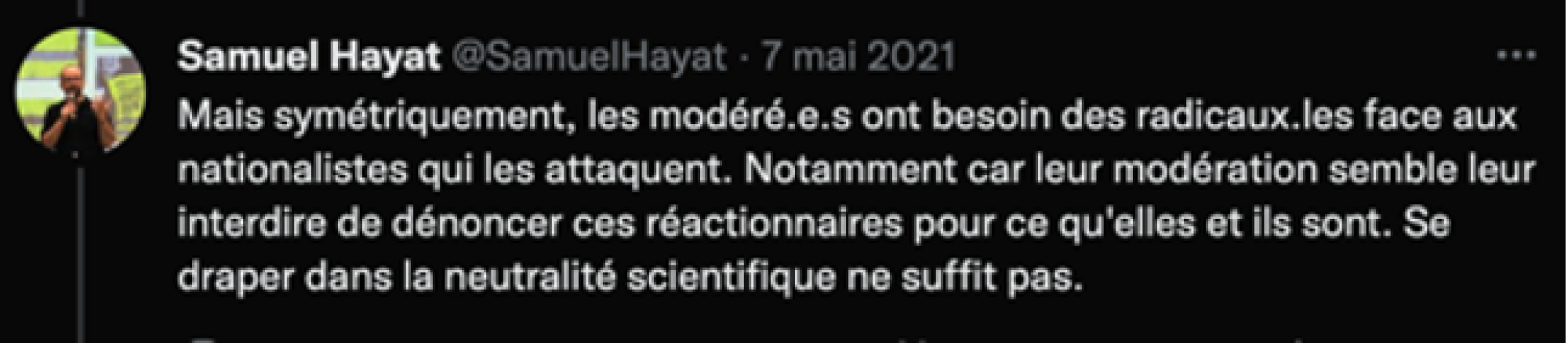

Far from being the heaven for intersectional sedition described by over 100 scholars in the French media in the following weeks, academia is in reality a site permeated with power relations and ideological confrontations (Bourdieu 2001). People of color researching race often denounce the difficulty they face in having their work recognized as legitimate, obtaining funding for doctoral research, and accessing posts in the French university system. This moral panic mobilizes an imagined version of academia and does not address scholars with important political messages (which are already marginalized inside the institution), but rather a broader spectrum of those using depoliticized, sugar-coated versions of concepts and epistemological production, often extracted from activist spaces. Intersectionality is put on display as a dividing line between “good” and “bad” scholars. This line is not drawn with regards to subversion or challenging of the symbolic order, but is instead aligned with strong reactionary positions. Several scholars and activists have expressed their frustration at seeing well-known academics with flourishing careers positioned as victims or revolutionaries, while between 2005 and 2016, their silence and even espousal of reactionary positions was telling. For example, in a twitter thread on May 7th 2021, Samuel Hayat, a political scientist at the CNRS, drew attention to the strategy aimed at intimidating the most moderate cohort:

1.jpg

(1) An unmistakable sign of the growing fascization of certain rightwing intellectuals: their preferred targets are no longer the most politically-engaged leftist intellectuals, but rather quite moderate figures, like Nonna Mayer or Michel Wieviorka.

2.png

(2) In doing so, they intend to show that no one will be spared: if you’re not explicitly in the nationalist camp, you are an enemy, and they will do anything to drag you down. Moderation won’t save you, but condemn you.

3.png

(3) This strategy aims at nothing less than intimidating and paralyzing the most moderate, so that the only remaining discourse opposing nationalists is that of the most radical leftists, which can be more easily manipulated to give rise to moral panic.

4.png

(4) It would be a mistake, for intellectuals on the radical left, to celebrate these attacks on centrists, or to think that such attacks don’t concern them. It would be both wrong and detrimental to suggest that there are only two camps: reaction or revolution.

5.png

(5) But inversely, moderates need radicals in the face of nationalists who attack them. Especially since their moderation appears to prevent them from denouncing these reactionaries for what they are. Hiding behind scientific neutrality is not enough.

For example, few members of what Samuel Hayat called the moderate, were vocal about the case of Akim Oualhaci, a French Arab postdoctoral sociologist working on the intersection of race, sports, and masculinity in France’s predominantly low-income immigrant neighborhoods. For three consecutive years, he was absent from the final list of candidates for admission to the CNRS (a prestigious public research institution with a highly competitive selection process). Each year, Akim Oualhaci was among the top three candidates selected by a first jury of peers, yet after the second jury – whose selection criteria is not made public – he was continually downgraded to the 9th position, thus failing to obtain a CNRS post. In 2019, Akim Oualhaci’s third downgrade sparked major outcry amongst scholars and researchers, with more than 200 signing a column denouncing the “relentlessness” of racial and classist (Mondoloni 2019) bias.

In a 2021 article, humanities scholars of color working on race and colonialism expressed worry over the push to subjugate academic freedom to an absolute secularism and other unnamed republican values, with the objective of further controlling research and education in a context of “reduced job security and neoliberal logics of knowledge production” (Belhadi 2020). The need for French critical race theory will certainly be interpreted as an attack against the Republic. France’s history has been deeply shaped by its role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, (neo)colonialism, Nazi collaboration, and systemic discrimination, and yet in 2018 the socialist government removed the word “race” from the constitution. This strategy of denial, far from making the racial question disappear, has heightened antagonism and exclusion. Indeed, the magic colorblind republican framework is incapable of addressing the consequences of centuries of violence, domination, erasure, and exclusion. The path to equality demands both political and intellectual strength and courage. Rather than framing the question in terms of “guilt” and “legitimization of violence,” the French government and intelligentsia should confront their history of colonialism and enslavement, as well as their neocolonial and systemically racist present.

The Enemy Within

One result of this mainstreaming of the term “intersectionality” is that since 2016 it has been at the heart of a political mêlée with politicians, media outlets, and academic institutions taking public stances “against intersectionality,” often parroting arguments made by white feminist organizations. The use of this specific set of accusations is not coincidental. Race is central to intersectionality, and it is also the notion that provokes the most fervent outcry and ideological opposition in France. Intersectionality therefore joins a growing list of terms identifying the “enemies within” who sow the seeds of the Republic’s destruction: Islamo-leftists, POC-only spaces, decolonialists, indigénistes.18 This has become a grab bag of trigger words all describing an amorphous enemy striving for a common goal: the annihilation of the united and undivided Republic.

By mapping intersectionality’s circulation, I wanted to demonstrate that a concept can be an instable vector of fragmentation and reconstruction while its definition, meaning, and usage also constitute sites of confrontation, appropriation, and opposition. We can identify five major moments of reconstruction since the appearance of intersectionality in France. The first one was the concept’s use by mainstream, predominately white feminist and LGBT organizations as well as Black, Arab, Muslim feminist and queer organizations. Secondly, we can identify the confrontation site around theoretical legitimacy between academia and activists of color. The third movement occurred when feminist and queer of color activists claimed independence from anti-racist organizations. The fourth phase of intersectionality’s circulation resulted in a new line of demarcation within the feminist and queer movement – between feminist, queer, and trans groups using intersectionality as the sole theoretical framework and those making political demands from a revolutionary standpoint, using the concept as a tool while highlighting its limitations. The last moment was when intersectionality was incorporated into the lexicon of the reactionary moral panic in France, as a racist, anti-feminist, and homophobic tool for mobilizing public emotions and as a warning to non-radical/political academics who could be tempted to uplift or work on race, decolonial, post-colonial, and gender and sexuality studies.

This final evolution shows us how, despite attempts to de-politicize, co-opt, and whitewash (Bilge 2015) the term, it seems that the gesture toward radical potential of intersectionality, a concept and critique stemming from Black feminist thought, resists and persists.

- 1. Coline Cardi’s work has shown how girls and women are systematically referred for psychological treatment and undergo longer-term and invisible social control.

- 2. “Cartographie des marges” in French

- 3. 1st or 2nd generation immigrants from former or current French colonies.

- 4. In the French context, suburbs (“banlieues”) are the American equivalent of inner-city neighborhoods with a considerable concentration of housing projects and low income non-white populations. In this article I will use the French “banlieue” to refer to these spaces and “banlieusard” to refer to the populations living there.

- 5. The expression BIPOC (Black Indigenous and People of Color) is not used in France. The name “Indigenous of the Republic” has to be understood in the framework of post-colonial immigration. “Indigenous” refers both to the parents and grandparents of French people of color and to the continued state control over those populations in regard to France’s (neo)colonial history. “Indigène de la République” is principally used by people from or close to this oganization, after the term “indigéniste” emerged in the public sphere, from the far right, right, and the left to oppose anti-racist movements, even those not linked to the “Parti des Indigénes de la République.”

- 6. Burned alive by her ex-boyfriend in Vitry-sur-Seine in 2002. The media impact of the case consolidated narratives around “suburban youth” and specifically “Arab youth.”

- 7. In France the term “racialized” is use to designate people of color. While aware that whiteness is also racialized I propose using the term here as “negatively racialized.”

- 8. This view was held by Baldwin while being disputed by Lorde.

- 9. AssiégéEs (Besieged) gathers people targeted by racism and hetero-patriarchy (women, queer, or trans people of color).

- 10. Lallab is an association for the rights, narratives, and representation of Muslim women. Queer et Trans Révolutionnaires (QTR) is “a working group of queer and trans descendants of postcolonial (im)migration focused on the fight against systemic racism and neocolonialism from a revolutionary perspective. QTR aims to put forward an autonomous queer and trans discourse in debates on decolonialism and anti-capitalism, and their links with gender and sexuality.” Nta Rajel is a Radical Feminist Muslim collective. Qitoko is a Trans of color collective. Mille et Une Queer is a Queer and Trans of color/banlieue collective.

- 11. An establishment run by a private association in a Paris banlieue, it was the scene of legal clashes following the firing of Fatima Afif, an employee, of the daycare on the grounds that she wore a hijab.

- 12. In 2011 Dominique Strauss-Kahn, a prominent politician from the socialist party, favorite for 2021 French presidential election, and the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was arrested in New York in a criminal case relating to allegations of sexual assault and attempted rape made by a Black hotel maid, Nafissatou Diallo.

- 13. The European Afro-feminist Festival organized by the Mwasi Collective.

- 14. The Decolonial Summer camp, was a 3-day summer training for people of color in France organized by activist Sihame Assbague and myself. The projects sparked a national controversy and backlash from newspapers to the French prime minister, as it was accused of “anti-white racism.”

- 15. Close to the figure of the scholar-activist in the US and the UK (we can cite here Paul Gilroy, bell hooks, Noam Chomsky, Judith Butler or Sylvia Federici), in France, public intellectuals (who can be considered activist-adjacent) navigate both media and political circles. Some were presidential advisors and participated in drafting political policy: Césaire, Fanon and Sartre with the French Communist Party; Simone de Beauvoir with the French Socialist Party; Raymond Aron with the Rassemblement du peuple français (a conservative party founded by General De Gaulle). At the same time, complaints are constantly voiced about “the death of intellectuals,” with popular TV shows, media outlets, and other mainstream content regularly showcasing social science academics (philosophers, sociologists, historians and economists). Most recently, Mediapart and the platform Kodo collaborated to create “Abécédaire des Savoirs” (The ABCs of Knowledge) where academics (predominately leftist) had one minute to define concepts within an Instagram format.

- 16. https://www.senat.fr/enseance/2020-2021/52/Amdt_234.html

- 17. In 2020 Actor Adèle Haenel walked out of the French César awards while shouting “Bravo, pedophilia!” after Roman Polanksi – child rapist – was announced to be the winner of the Best Director award for his film An Officer and a Spy.

- 18. In reference to the activist group Parti des Indigènes de la République.

Abdallah, Mogniss H. 2002. “1983 : La marche pour l’égalité.” Plein droit 55(4):37–40.

Amaouche, Malika. 2015. “Les gouines of color sont-elles des indigènes comme les autres ? À celles et à ceux qui nous reprochent de diviser la classe des femmes.” Vacarme 72(3):159–69.

Bailey, Moya, and Trudy. 2018. “On Misogynoir: Citation, Erasure, and Plagiarism.” Feminist Media Studies 18(4):762–68.

Belhadi, Sarah. 2020. “L’association des chercheurs de la pensée critique avec le terrorisme est une accusation très grave.” Bondy Blog. https://www.bondyblog.fr/societe/education/lassociation-des-chercheurs-d...

Bilge, Sirma. 2015. “Le blanchiment de l’intersectionnalité.” Recherches féministes 28(2):9–32.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2001. La Sociologie est un sport de combat. Paris: Editions Montparnasse.

Cardi, Coline. 2007. “Le contrôle social réservé aux femmes : Entre prison, justice et travail social.” Déviance et Société 31(1):3–23.

Collectif AssiégéEs. 2015. “AssiégéEs vous présente son premier numéro : L’Étau.” AssiégéEs (1). https://issuu.com/assiege-e-s/docs/maquette_assiegees_3eme_couv_essai

Collectif AssiégéES. 2015b. “1er mai : cortège assiégées et mwasi- collectif afroféministe.” AssiégéEs Blog. http://www.xn--assig-e-s-e4ab.com/index.php/blog/34-1er-mai-cortere-assi...

Collectif Féministes Indigènes. 2007. “Appel Des Féministes Indigènes.” Bellaciao. https://bellaciao.org/fr/Appel-des-Feministes-Indigenes

Collective of Academics. 2020. “Une centaine d’universitaires alertent : « Sur l’islamisme, ce qui nous menace, c’est la persistance du déni ».” Le Monde, October 31. https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2020/10/31/une-centaine-d-universit...

Crenshaw, Kimberlé W., and Oristelle Bonis. 2005. “Cartographies des marges : intersectionnalité, politique de l’identité et violences contre les femmes de couleur.” Cahiers Du Genre (2):51–82. https://www.cairn.info/journal-cahiers-du-genre-2005-2-page-51.htm

Dalibert, Marion. 2013. “Authentification et légitimation d’un problème de société par les journalistes : les violences de genre en banlieue dans la médiatisation de Ni putes ni soumises.” Études de communication 40(1):167–80.

Farris, Sara R. 2017. In the Name of Women’s Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Glover, Cameron. 2017. “Intersectionality Ain’t for White Women.” Wear Your Voice. https://wearyourvoicemag.com/identities/feminism/intersectionality-aint-....

Gramaglia, Juliette, and Tony Le Pennec. 2019. “‘Universalistes’ contre ‘intersectionnelles’: à chaque media ses féministes” [“‘universalists’ versus ‘intersectionals’: every camp has their feminists”]. Arrêt sur Image. https://www.arretsurimages.net/articles/feministes-universalistes-contre...

Greenfield-Sanders, Timothy (Dir.). 2019. Toni Morrison: The Pieces I am [documentary]. New York: Magnolia Pictures.

Groupe du 6 novembre. 2021. “WARRIORS GUERRIERES - Présentation.” Coordination lesbienne en France. https://www.coordinationlesbienne.org/spip.php?article141

Guénif-Souilamas, Nacira. 2006. “La Française voilée, la beurette, le garçon arabe et le musulman laïc. Les figures assignées du racisme vertueux.” La république mise à nu par son immigration. Paris: La Fabrique, 109–32.

Guénif-Souilamas, Nacira, and Éric Macé. 2004. Les féministes et le garçon arabe. La Tour-d’Aigues: Editions de l’Aube.

Hamel, Christelle. 2003. “'Faire tourner les meufs'. Les viols collectifs : discours des médias et des agresseurs.” Gradhiva : Revue d’Histoire et d’archive d’anthropologie, Musée du quai Branly.

hooks, bell, and Tanya McKinnon. 1996. “Sisterhood: Beyond Public and Private.” Signs 21(4):814–29.

Larcher, Silyane. 2015. “Troubles dans la « race ». De quelques fractures et points aveugles de l’antiracisme français contemporain.” L’Homme La Societe (4):213–29.

Mohammed, Marwan. 2016. Islamophobie : comment les élites françaises fabriquent le "problème musulman". Paris: La Découverte.

Mondoloni, Matthieu. 2019. “Soupçons de discriminations au CNRS : 200 universitaires dénoncent un ‘acharnement’ contre un candidat recalé trois fois.” France info, June 20. https://www.francetvinfo.fr/sciences/soupcons-de-discriminations-au-cnrs...

Mwasi. 2020. Afrofem. Paris: Syllepse.

Nash, Jennifer C. 2018. Black feminism reimagined: After intersectionality. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Poingt, Guillaume. 2021. “« Il a beaucoup changé depuis qu’il traîne avec sa copine »: quel engrenage a conduit à la mort d’Alisha à Argenteuil ?” Le Figaro, March 16. https://www.lefigaro.fr/faits-divers/theo-a-beaucoup-change-depuis-qu-il...

Provitola, Blase A. 2019. “In Visibilities: The Groupe du 6 Novembre and the Production of Liberal Lesbian Identity in Contemporary France.” Modern & Contemporary France 27(2):223–41.

Queer et Trans Révolutionnaire. 2017. “Pour une lutte queer révolutionnaire en France.” Queer & Trans Révolutionnaires, February 22. https://qtresistance.wordpress.com/2017/02/22/pour-une-lutte-queer-revol...

Réseau Classe/Genre/Race. 2015. Discriminations classe/genre/race, repères pour comprendre et agir contre les discriminations que subissent les femmes issues de l'immigration post-coloniale. https://www.facebook.com/ClasseGenreRace/photos/a.1656290357948965/16562...

Smith, Ben. 2020. “The President vs. the American Media.” The New York Times, November 15. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/15/business/media/macron-france-terroris...

Taharount, Karim. 2019. “« Justice en banlieue » : une affiche de campagne du Mouvement de l’Immigration et des Banlieues (1997).” Parlement[s], Revue d’histoire politique 30(3):138–54.

Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. 2017. How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Toni Morrison. 1996. Sula. New York: Vintage.

Vuattoux, Arthur. 2021. Adolescences Sous Contrôle. Paris: Presses de SciencesPo.