We (Still) Kill the Old Way: The Conundrums of Organising Rage in Tripoli

Perché Tripoli? Perché Tripoli

The Italian word “perché” carries both meanings of “why” and “because.” Alicia Imperiale touched on this duality while writing the editorial for the Fall 2021 issue of Log magazine on architecture, titled “Perché Italia? Perché Italia…” She briefly reflected on the contradictory nature of the word, seeing it as symbolic of the “many understandings, and perhaps misunderstandings” (2021:8), of a subject – Italy, in her case; Tripoli, in ours. “Perché” serves as both a conjunction and an interrogative word. This duality creates a tension between questioning and explaining, cause and reason, showing that “perché” not only seeks an explanation but also provides one.

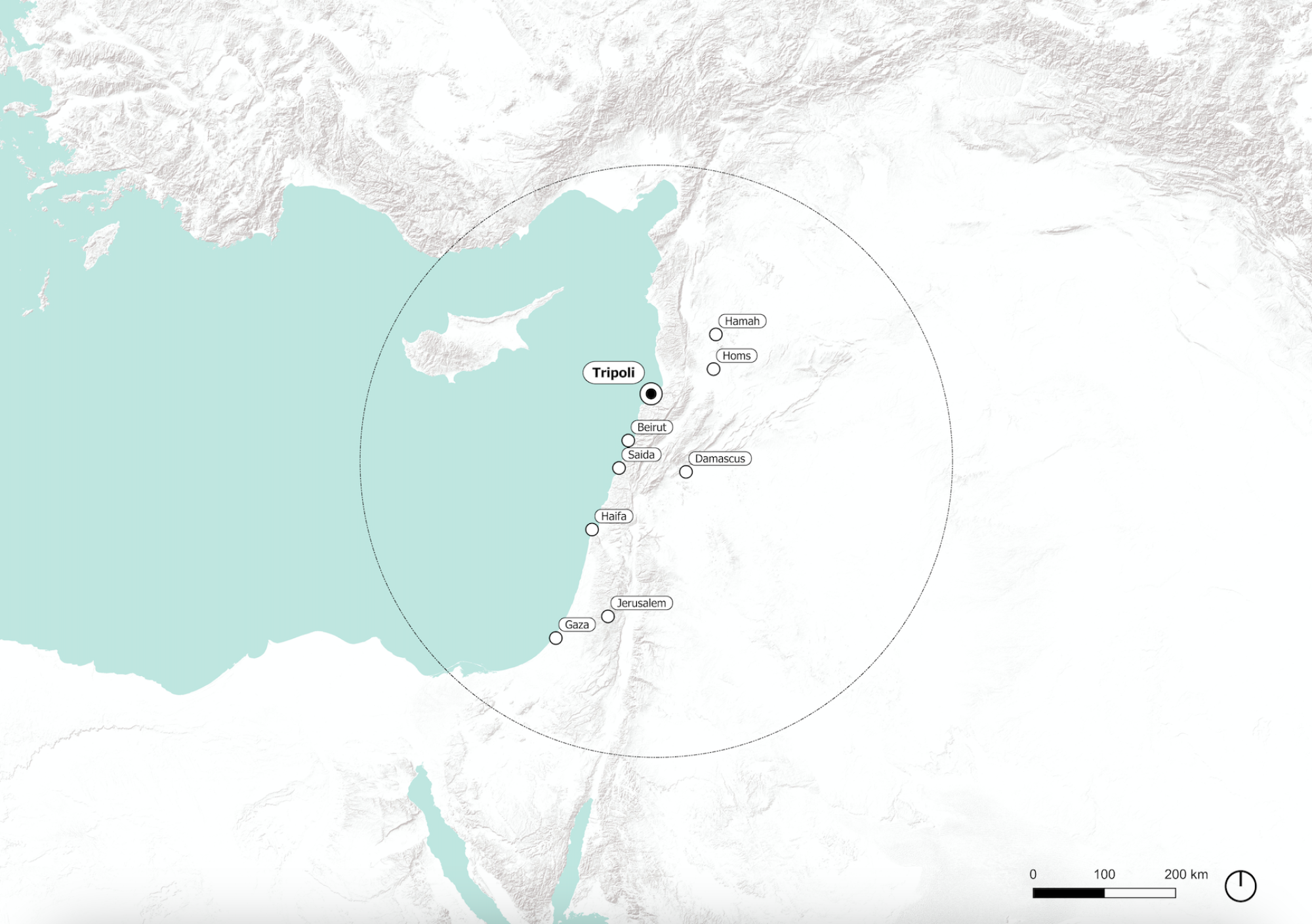

When we ask, “Why Tripoli?,” we don’t uncover a singular, simple, direct answer. Instead, the complexity deepens as we explore the city’s history, focusing on a moment when the unresolved contradictions of “independent Lebanon” during the so-called “golden 30 years,” came to a head – within the city that the Lebanese polity perceives as too dangerous to be left uncontrolled.

screenshot_2024-12-03_at_05.20.50.png

Map designed by Amer Jbeili

“In history, as in cinema,” Carlo Ginzburg (2022) asserts, “every close-up implies an off-screen scene.” ‘Alī ‘Akkāwī was born in Tripoli among countless Palestinian families displaced by the 1948 war. His story, traced in glimpses across three decades in the popular and populous Bāb al-Tabbānè (Hay Gate), is one such close-up.

r_trip_rast_2_1.png

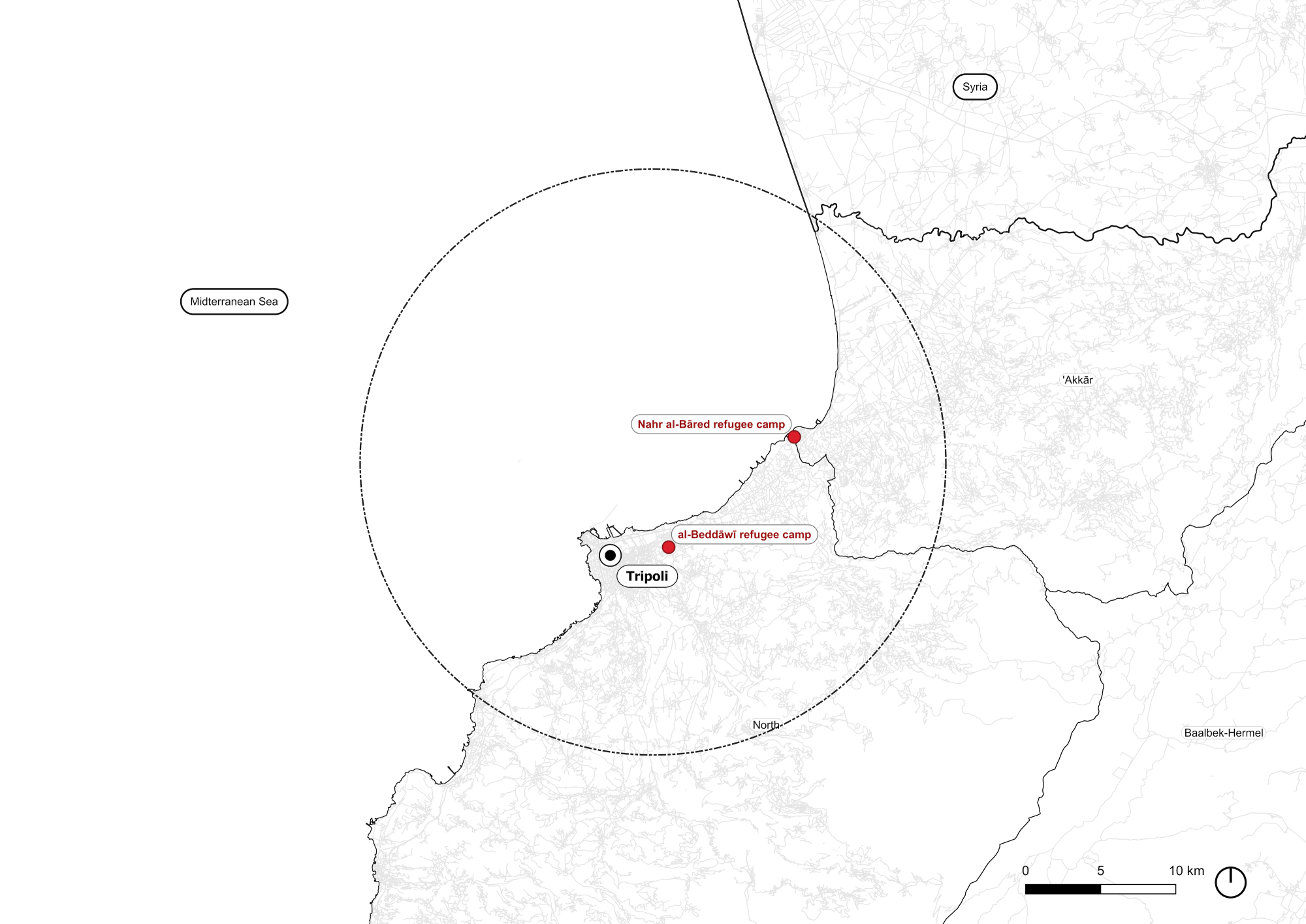

Map designed by Amer Jbeili

Being the lifeblood of Tripoli’s hay and vegetable trade, and its gateway to the northern plain, al-Tabbānè became the primary destination for rural-urban migrant peasants from 'Akkār. Positioned midway between the latter and the quarter, the Nahr al-Bāred refugee camp was established in 1949. The city’s river, Abū ‘Alī, historically recognised as “wrathful” for its floods, overflowed disastrously in 1955. Waves of Palestinians and Lebanese were driven into the already overcrowded quarter; soon after, al-Beddāwī refugee camp took root in its eastern vicinity.

r_trip_rast_3_1.png

Map designed by Amer Jbeili

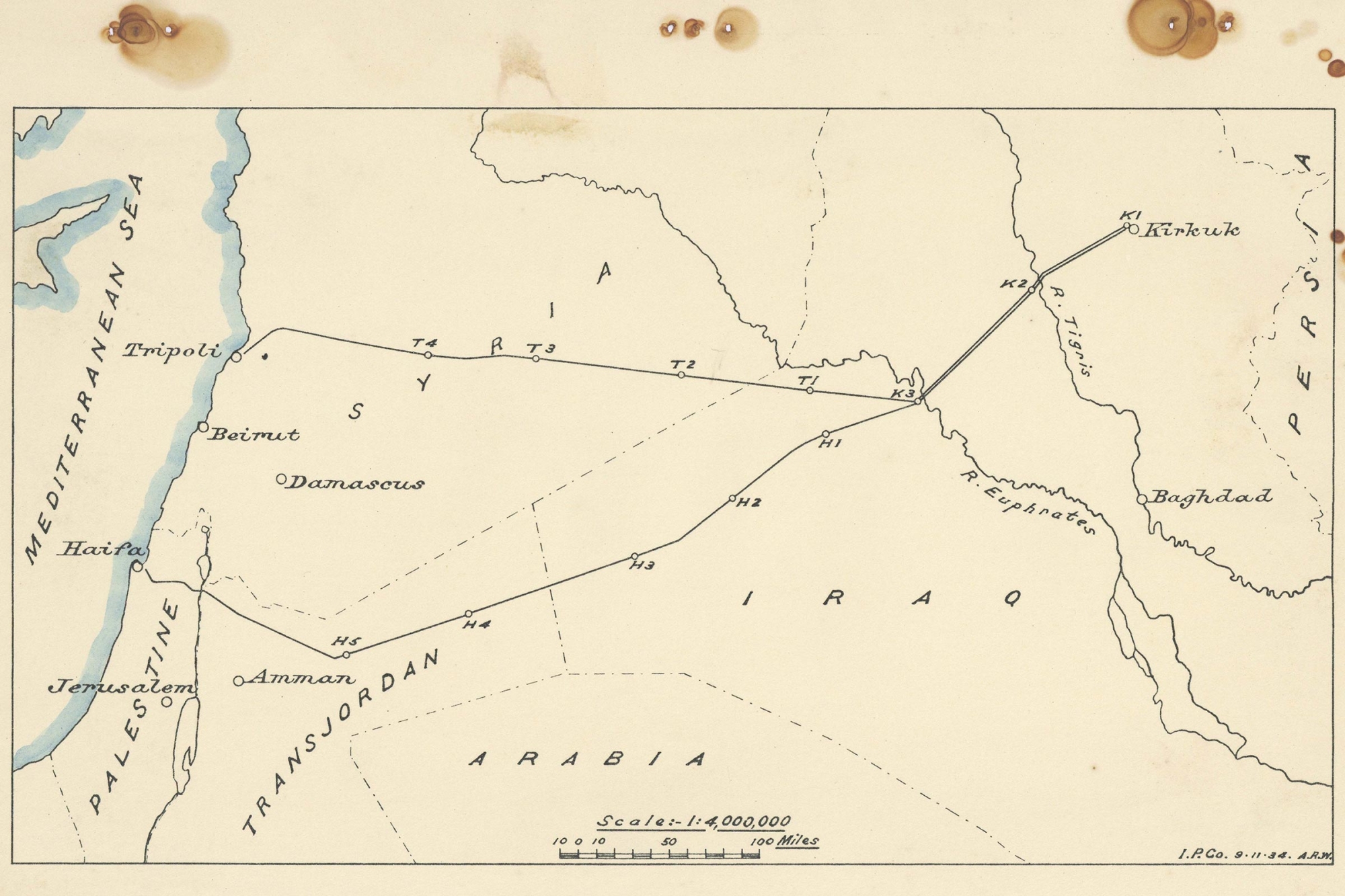

Just next door to the quarter and the camps, the British Iraqi Petroleum Company’s oil installations at Tripoli’s terminal attracted rural-urban migrants since the 1930s and Palestinian refugee workers from the former Ḥayfā terminal following the 1948 war.

The location of the pumping stations (Kirkuk) and terminals (Ḥayfā & Tripoli).

Gulbenkian Archives, November 9, 1934.1

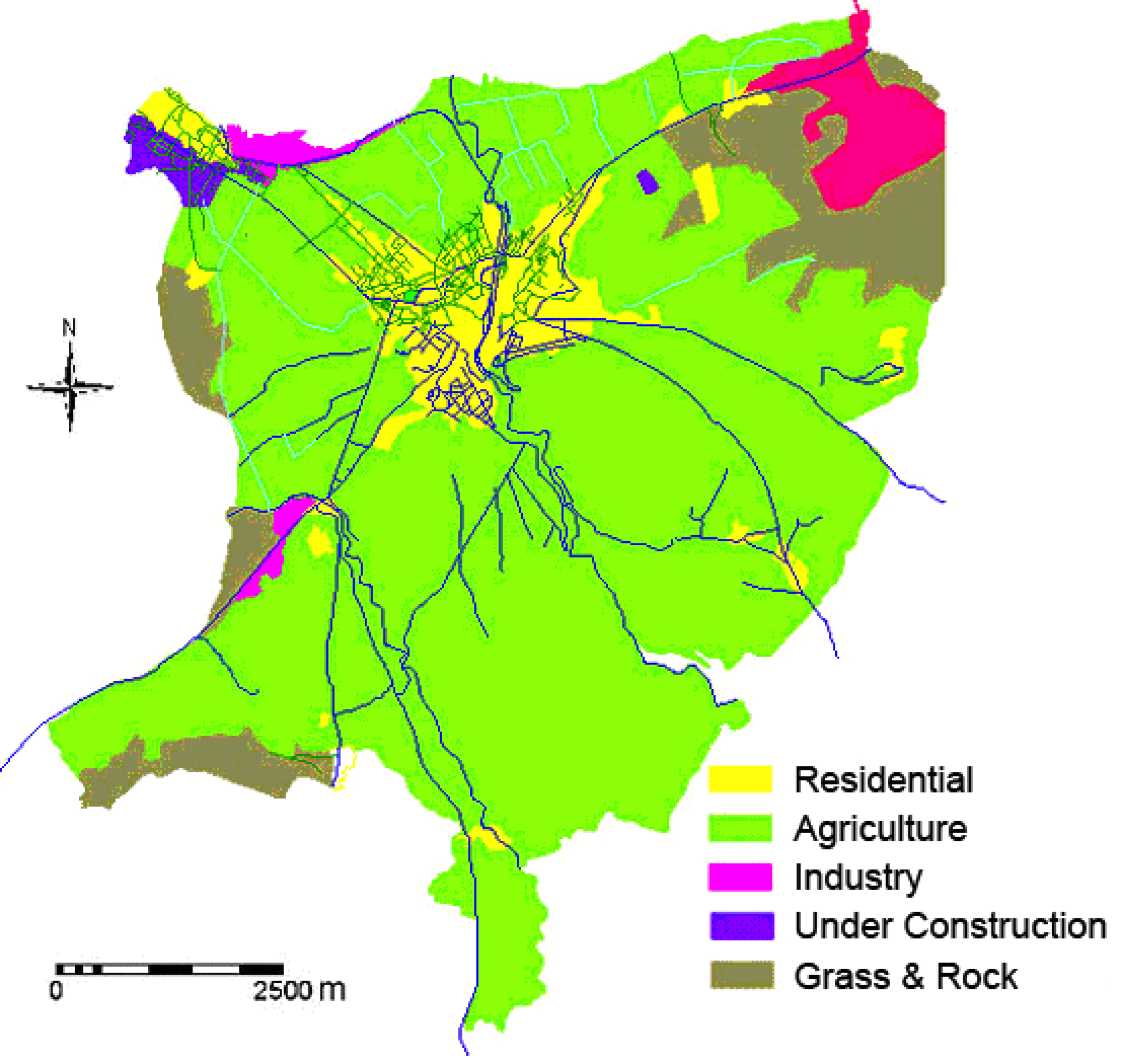

The 1956 land use map of Tripoli shows the quarter on the bounds of the city’s northern agricultural zone: an intersection between the IPC industrial zone to the east, which begins the route to the ‘Akkār plain, and the port zone to the west, connecting to the Mediterranean Sea.

The 1956 land use map of Tripoli, prepared by Khaled El Nabbout.2

Note: al-Beddāwī camp is in purple, under construction at the city's northeastern edge and adjacent to the quarter.

That said, these were not merely geographical crossroads. Displacement, migration, and a complex web of social, national, regional, and international struggles shaped not only ‘Akkāwī’s fate but that of an entire generation.

One Way or Another

On the fifth day of the 1967 war, riots surged through Tripoli. Fueled by the defeat and outrage over the Lebanese government’s neutral stance in the Arab-Israeli war, it culminated in sabotaging the governmental buildings (Ziadeh 2011:23-40). ‘Akkāwī, present then as a news correspondent, channelled momentum through the “Five Revolutionaries” cell to purge intelligence informants from the quarter. Those same informants were responsible for sending many militants, including his sixteen-year-old self, to prison. In 1963, he had been arrested and sentenced to three years for “mobilising a few youngsters” (Seurat 2012:261) against the Arab Socialist Ba‘th [Renaissance] Party branch in Tripoli, during clashes between the Movement of Arab Nationalists (MAN) and the Ba‘th Party over reunification. Later in 1967, he took combat training at the MAN’s newly formed Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP)3 and spent the next year in the Palestinian guerilla camps. Yet, by early 1969, the Front fractured, torn apart by internal debates over ideology and their stances toward Arab regimes. Countless Marxist-Leninist organisations, fronts, and parties emerged from MAN’s fragmentation,4 one of which was the Organisation of Rage in al-Tabbānè, co-founded by ‘Akkāwī (Lefèvre 2021:98-106). The fracture marked a complete shift from Arab Social Nationalism inspired by Jamāl ‘Abdulnāṣer, to Third World Socialism inspired by the trilogy of the Algerian, Cuban, and Vietnamese revolutions, as well as China’s cultural revolution, whose chairman, Mao Tse-tung, had already addressed Arabs in 1965: “Israel and Formosa [Taiwan] are bases of imperialism in Asia. You are the gate of the great continent and we are the rear. They created Israel for you, and Formosa for us” (as cited in Harris 1977:127).

The gradual disillusionment with Arab Social Nationalism happened through consecutive setbacks. The 1958 Lebanese reconciliation government emerged as a compromise between the National Unity Front and the American-backed opposition, with Fū’ād Shehab as president, elected under the watchful eyes of Eisenhower and ‘Abdulnāṣer – consequently undermining the popular push for unity with the United Arab Republic of Egypt and Syria (UAR). Just three years later, the dramatic collapse of the UAR exposed the deep gap between nationalist rhetoric and reality. Since 1963, failed attempts to revive this unity, combined with escalating public hostilities between nationalist regimes and parties in Egypt, Iraq, and Syria further eroded its legitimacy. The 1967 defeat dealt the final blow to Arab Social Nationalism, sealing its fate. By 1970, its promises had been dismantled, marked by Egypt’s acceptance of the Rogers Plan5 and the bloodshed of Jordan’s Black September. In a final symbolic turn, the sudden death of ‘Abdulnāṣer was the final nail in the coffin of an ideology that had once inspired the disillusioned militants of 1948 but had ultimately led them to face the bitter reality that their grand aspirations had been systematically shattered, piece by piece.

By 1969, Jordan and Lebanon were still determined to block Palestinian guerrilla attacks from being launched within their borders. At this point, more Palestinians attempting to cross the borders were killed by the armies of these countries than by Israelis (Jabber 1973:174). Yet, 1969 marked the peak of the armed struggle, with even communist parties organising partisan bands. In the hills near Tripoli, the PLO had already set up a training camp (Lefèvre 2021:66). Among the militants trained there was Muḥammad al-Ṣayyādī. On the 18th of August 1969, tens of thousands flooded the streets of Tripoli for his funeral procession, but just ten days later, numerous clashes with the Lebanese authorities led to an armed revolt that spread across Lebanon. Over 76 police stations and the mediaeval castle were occupied in Tripoli and remained beyond state control until the Cairo Accord settled the nationwide crisis, deeming the Palestinian guerillas an extended liberty to operate from Southern Lebanon and manage the refugee camps’ affairs (Sab‘īn 2018).

The funeral procession, 18th of August 1969.

Nidal al-Sabeh’s archive, shared by the Facebook page Tripoli in Black & White.6

Disenchanted by what they viewed as nothing more than a superficial concession through the Cairo Accords – a stalling tactic before the state would inevitably move against them, ‘Akkāwī and his comrades determined that only a state of permanent revolution could preserve and expand the liberties gained through guerrilla warfare in Lebanon (Fakhr 1969:6-7). They hence transformed their quarter into an urban revolutionary stronghold serving the peasant revolt in ‘Akkār plain, which began during that autumn and persisted until the 30th of October, 1970. The revolt was met with a brutal crackdown by security forces, who killed, arrested, and expelled peasants (Kamāl 1970:8-9). The campaign had been ordered by the newly elected Lebanese President Slaymān Franjiyyè, just two weeks before a coup in Syria that ousted the radical Ba‘th leadership, and brought Ḥāfeẓ al-Asad, the Syrian defence minister, to power.

Despite their origins at extreme ends – Franjiyyè from a feudalist family in the mountainous Zghartā south of ‘Akkār, and al-Asad from a peasant family in the northern mountainous al-Qardāḥa – their paths crossed in ‘Akkār. Franjiyyè sought to assert authority as a step to overturn the Cairo Accords, which he deemed a violation of sovereignty. While al-Asad had already made his stance clear by withholding air support during the bloodsheds of Black September in Jordan, he was determined to avoid any intervention that could leave the military with a black eye, and also sought to weaken any resistance to this order – thus turning the revolutionary zeal of the 1960s Syrian regime into a cold, calculated strategy for consolidating power.

By the mid-to-late 1960s, Arab states began confronting their long-repressed anxieties over the creation of Israel. Initially, they had no real issue with the Palestinians, as long as their status remained that of refugees, and their plight was framed as a humanitarian crisis. However, the Palestinian Question is a political issue, not simply a socio-economic problem to be solved through aid or housing initiatives. The 1967 war forced said states to confront an uncomfortable reality: to challenge Israel meant to challenge the global order dominated by American and European hegemony, as the war was not an isolated incident. It was part of a broader, aggressive international storm, stretching from Indonesia to Ghana.

In response, the Arab regimes sought to contain Israeli expansion diplomatically, hoping Western powers would broker a settlement with clearly defined borders – an attempt to avoid the steep cost of challenging the global power structure head-on. This left the regimes divided over how to handle the growing Palestinian guerrilla movement. Some saw the guerrillas as a way to channel public frustration without engaging in full-scale war. However, they believed the guerrillas had to be kept under control to avoid unpredictable consequences. Others, labelled “defeatist regimes,” were convinced that the growing guerilla operations would provoke greater Israeli retaliation and expansion. Lebanon, having always remained de facto neutral during the Arab-Israeli wars after 1948, was a member state of this “defeatist” camp.

Whence, the militancy of the Palestinian guerrillas, along with their Arab counterparts, became something that had to be suppressed at all costs. By 1971, as the crisis persisted, the authorities’ response escalated beyond deploying security forces. They reframed the issue as a sectarian conspiracy, blaming Syrian “Alawite” peasants and the Palestinian guerillas for the unrest. On the 17th of May, 1971, an anonymous, high-ranking security official reported to the press:

In Ba‘l Muḥsen and Ba‘l al-Sarāqba neighbourhoods of al-Tabbānè quarter, the majority of residents, around 40,000, are Alawites, primarily Syrians. Their community essentially functions as a ghetto, particularly in Ba‘l Muḥsen, where non-Alawite residents are virtually nonexistent. Their ties to Syria, their country of origin, are profoundly strong, with some families split between living in both countries [...] It’s challenging to understand what’s happening in these Alawite neighbourhoods as they keep to themselves and avoid interacting with others. However, during recent events, it was observed that many have acquired modern weaponry, and some have begun infiltrating neighbouring areas [...] The real motive behind many Alawites moving to Tripoli isn’t for employment, as they claim, but rather to incite unrest, disrupt security, and sow division. Otherwise, why would they be armed when they have no conflicts with other communities? [...] (Samāḥa August 22 1974:7).

In contrast to the picture painted by security officials, among the peasants' demands were many basic rights regarding human dignity, such as the right to bury their dead in their own villages, and the drafting of laws that forbid landlords from exploiting peasants’ wives and children “for their own purposes” (Kamāl 1970:8-9). In other words, both the Syrian and Lebanese regimes sought together to establish control over the ‘Akkār plain by quashing the peasant insurgency, while the uprising insisted to go against “political feudalism,” thus exposing both regimes’ ideology as one of division across sectarian lines for capitalist purposes.

Property is (No Longer) a Theft

After 1948, Beirut replaced Ḥayfā as the commercial trade capital of the region. After 1956, it had also replaced Cairo as the region’s gateway for European business interests. With its prime location, lack of currency controls, and airtight bank secrecy laws, Beirut transformed into a refuge for hot money and a sanctuary for flight capital. In the decades that followed, Lebanon’s banking sector boomed. Deposits soared 38 times over, and by 1974, the ratio of deposits to national income had spiked to a staggering 122 percent – the highest in the world. Between 1950 and 1965, the Lebanese and Arab bourgeoisie fueled this expansion, with banks multiplying from just ten to 55 (Nasr 1978:4).

In 1966, political instability, international monetary crisis, and rising Western interest rates, led to the collapse of the Lebanese banking sector. The number of Lebanese banks plummeted from 55 in 1966 to just 25 by 1974, as multinational banks seized control and asserted near-total monopoly when Lebanese banks saw their market share collapse from 30% in 1966 to about 15% in 1975 (ibid.).

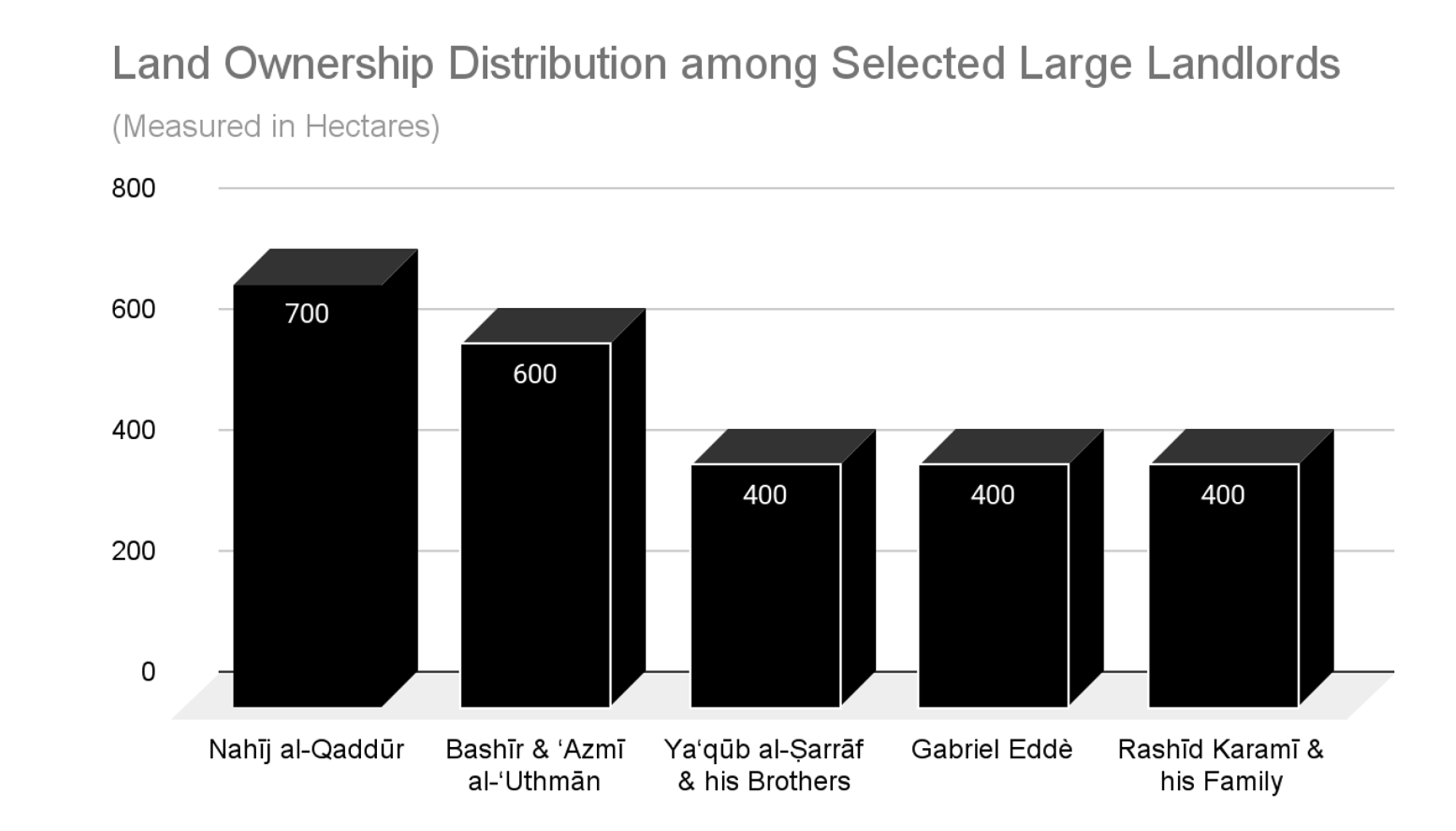

Concurrently, rural Lebanon underwent a profound transformation since the early 1950s, marked by the rise and spread of large capitalist farms. Instead of evolving through consolidating small and medium-sized peasant holdings, these large farms were established by acquisition of land from declining or absentee feudalist landlords. The shift was largely driven by the emergence of an agro-exporting bourgeoisie (Nasr 1978:6). In ‘Akkār, they were the merchants, notables, and administrators from cities like Tripoli (Karāmī and al-Sha‘rānī), Sidon (al-Shammā‘), Anṭelyās (Abū Jawdè), and Mount Lebanon (Eddè), as well as the Palestinians Sa‘īd Rāgheb and Abū Hishām Sayfeddīn (Samāḥa August 20 1974:7).

By the early 1970s, the exploitation of peasants in Lebanon manifested primarily in three ways according to Salim Nasr, one of which was the monopolisation of agricultural inputs. The import of chemical fertilisers for instance, the share of which reached 30 percent in the cost of production, was “concentrated in the hands of two big local firms, Unifert and Le Comptoir Agricole” (Nasr 1978:8).

One ‘Akkāri peasant lamented to the press in 1971: “Formerly, producing 1 kilo of cucumbers cost only LL 3, now it’s 100 [...] The fertilisers now used were unfamiliar to peasants, who now have to bear the cost; one ton of fertiliser costs LL 180, and each hectare requires a ton of fertiliser. Everything is expensive now” (Samāḥa August 21 1974:7).

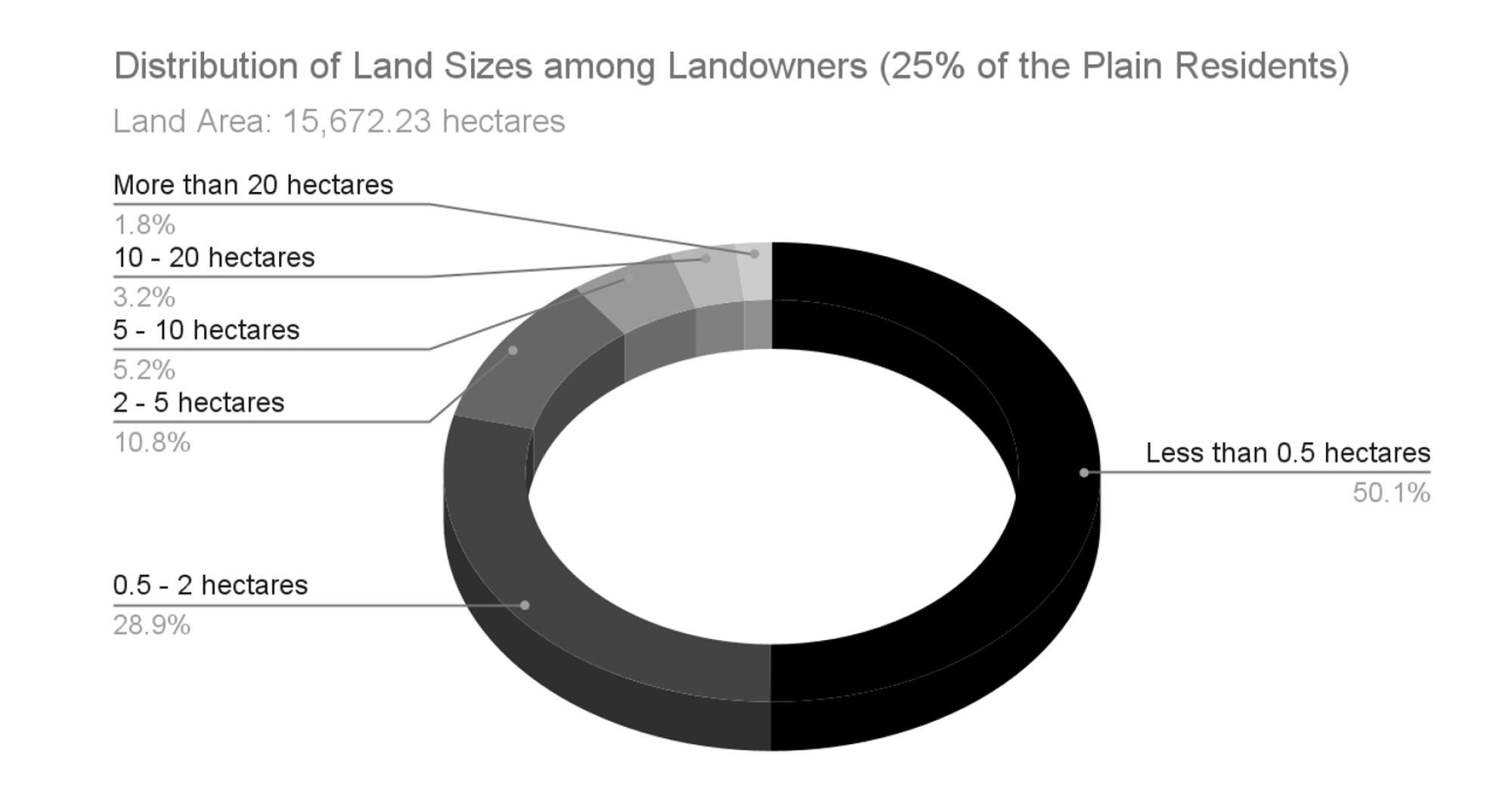

Moreover, the situation in ‘Akkār was significantly atrocious when it came to land ownership. One peasant illustrated the situation by testifying that “the Eddé family prevents our herds from accessing the water channels, something unheard of since the days of Turkish rule” (Samāḥa August 20 1974:7). Only 25% of ‘Akkār plain residents owned any land at all, with just 1.8% among them owning more than 20 hectares in an area of 15,672.23 hectares (ibid.)

screenshot_2024-12-03_at_04.39.04.png

Data extracted from Joseph Samāḥa’s investigative articles published by Assafir in 1974, which delved into the ‘Akkār peasants’ revolts between 1969 and 1974. Charts designed by the author.

Though the borders between Lebanon and Syria cut through ‘Akkār, the vast properties of the large landlords roamed unchecked across them. One such landlord, Jamīl Melḥem, owned an extensive 4,000 hectares of land exclusively in Syria – which he lost with the land reforms, implemented during the UAR era (ibid.). Some landlords offset their losses of villages in Syria by shifting to capital-intensive farming methods. Others chose to sell their land, either to rival landlords or to those capitalist investors who recognized the potential of the ‘Akkār plain as a lucrative region, particularly for capital-intensive citrus cultivation (Gilsenan 1990).

In 1970, “twenty intermediaries controlled 80 percent of the marketing of citrus, the main three controlling a third of the crop” (Nasr 1978:8). This control over marketing was the second key factor in the exploitation of peasants in Lebanon. Production, whether aimed at local or regional markets, was largely bought by a few dominant traders who controlled the financial resources, transportation, storage, and distribution channels. This control seals the peasants’ dependence on the trader, who could then impose very low prices on the producers while charging high prices to consumers, thereby pocketing the difference (ibid.).

Credit and usury are identified as a third aspect of peasant exploitation in Lebanon by Nasr. The private financial and commercial sector dominated over the public sector, with agricultural credits rising from LL 50 million in 1950 to LL 160 million by 1973. In that same period, the total interest paid by producers was estimated at LL 45 million annually, equating to “35 percent of the total annual credits” (ibid.).

To Western capitalists and finance institutions, Lebanon had indeed become the Switzerland of the Middle East (Merhej 2021). In contrast, the 1960-1961 IRFED report7 offered a different perspective regarding al-Tabbānè. It noted that “90 percent of the inhabitants are lower class,” that it is, although it is on the whole recent in construction, “generally dirty and in bad repair, with poorly drained streets,” and that “few people older than twenty years have had more than a primary education” (IFRED 1963:5-6, as cited in Gulick 1967:205-206). The report described the shabby “lower class cafes and small hotels connected with bus traffic to and from Syria,” which must have been serving the “20,000 immigrants from Syria who do the kinds of work no one else is willing to do,” as mentioned by Tripoli’s municipal chairperson (Gulick 1967:206). “It is reasonable,” he said, to assume that most of them lived in al-Tabbānè and Ba‘l al-Sarāqba, and added that “these sections have the reputation of being tough, dangerous, and unwholesome, and the concentration of ‘Alawites in them is a generally known fact” (ibid.).

Over the decades preceding this report, Tripoli underwent a profound yet gradual process of social restructuring and spatial segregation. Reports of Ottoman officials observed the affluent class dominated by merchants and landlords dotting the outskirts of the old city with mansions, while the middle class was largely made up of farmers, and the lower class consisted of labourers in factories, orchards, fishing, and other “menial” lines of work – with the latter class residing in the “worst quarters” (Al Tamīmi and Bahjat 1987:227). During the French Mandate era, urban expansion proceeded apace; nonetheless, it wasn’t until after the December 1955 flood – which severely damaged much of the old city – and the resolution of the 1958 crisis which drove the middle class to embrace the state’s modernisation projects, that the centuries-old neighbourhoods were abandoned for the modern boulevards and districts.

The modernisation projects sweeping through the city devoured its agricultural zones, a lifeline for rural-urban migrants who had replaced the middle class in the old city. By 1961, unemployment in the Ba‘l al-Sarāqba neighbourhood had soared to 25% (Gulick 1967:206). The relentless destruction of orchards to make way for new developments exacerbated the plight of these migrants. As the long postwar boom faded in the mid-seventies, a global economic crisis took hold, marked by plummeting output and spiralling inflation that devastated the working class.

The old city soon earned a reputation as a “Fugitive City-State,” a haven for bands of outlaws who were a mix of Lebanese and Syrian rural-urban migrants, orphans, workers, partisans of the Socialist Movements and militants of the Palestinian Revolution, or former soldiers in the Lebanese and Syrian armies. Together, they were the wretched of the city and encapsulated the plight of all the residents within this city-state.

At the dawn of the 5th of January, 1975, four months before the outbreak of Lebanon’s Two-Years War, the army and security forces coordinated an operation to storm the old neighbourhoods of Tripoli and dragged the residents to the streets to investigate their identities and affiliations to those fugitives (Attamaddon 2017). Pierre Gemayel, founder of the proto-fascist Christian party al-Katā’eb [the Phalanges], came out to address the media: “Our wealth lies not in petroleum like that of others; it resides in security, entrepreneurship, Arab capital [investments], trade, banking, and tourism. All these elements can only thrive in a secured environment, and the greatest responsibility that can be fulfilled for Lebanon is for the state and its security forces to assert their authority and maintain control” (ibid.).

The Arab-Israeli wars, coupled with Egypt, Iraq, and Syria’s nationalisation efforts in the 1960s ultimately benefited the Lebanese bourgeoisie. Lebanon emerged as a broker between Arab petroleum capital and Euro-American financial centres, while also serving as a safe haven for capital fleeing Egypt, Iraq, and Syria. This shift allowed Beirut to eclipse not only Cairo and Ḥayfā but also Baghdād and Damascus as the region’s commercial hub. However, Lebanon found itself adopting two contradictory approaches towards Israel: on the one hand, there was a concern that any potential peace agreements between Arab nations and Israel could jeopardise Lebanon’s profitable position as a financial intermediary. On the other hand, battling Israel risked going against the global order, a high-risk route that Lebanon refrained from pursuing. Therefore, maintaining both the national and regional status quo became essential, with a commitment to steering clear of danger for Lebanon’s banking and finance sectors, as well as its southern borders. As a result, the state cracked down on any faction that threatened this paradoxical balance, and the way it dealt with “The Organisation of Rage” brought its own project of sectarian monopoly capitalism to light.

(Investigation of) a Citizen Above Suspicion

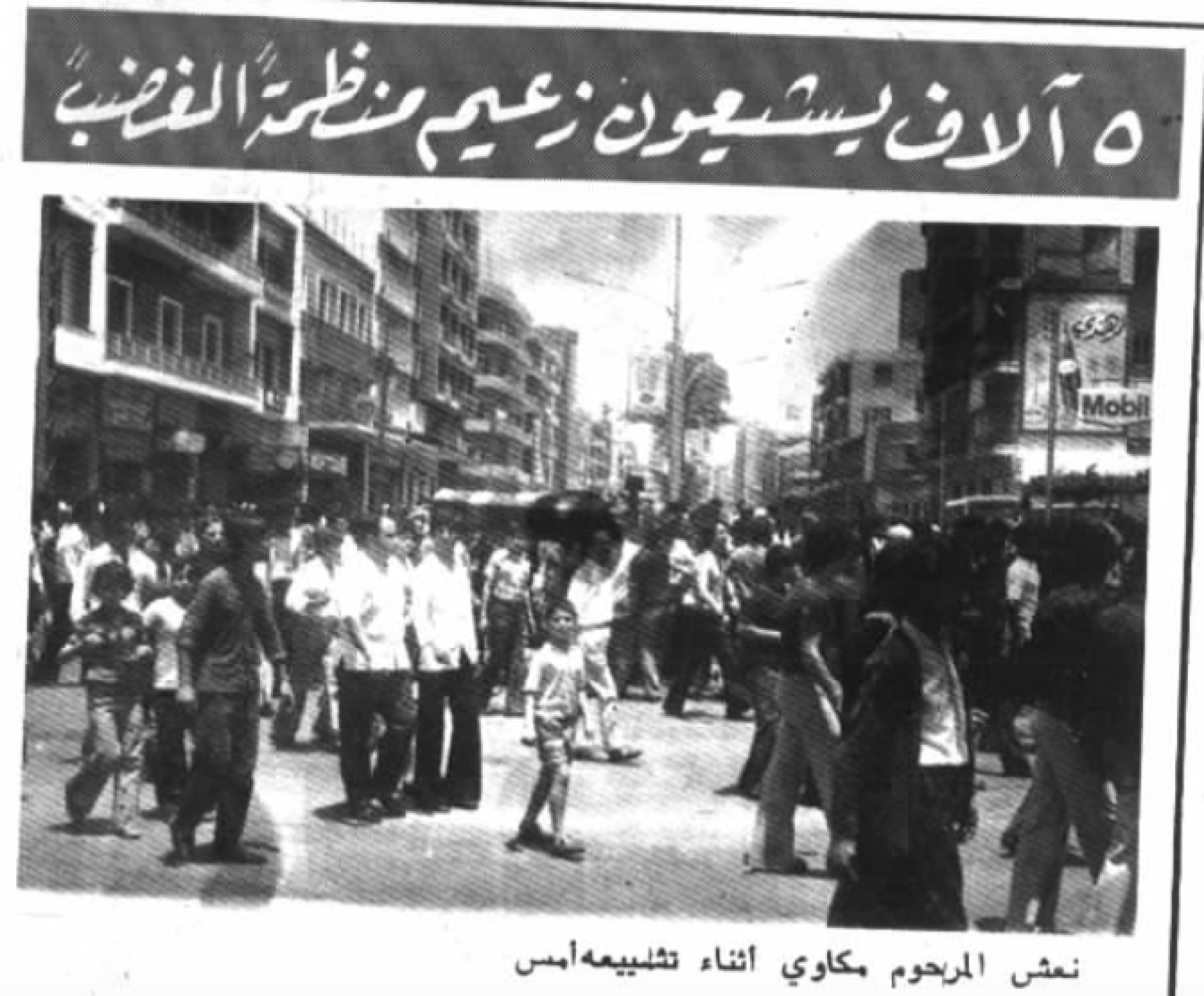

By 1971, “The Organisation of Rage” did not wither away. It was still carrying on its “revolutionary violence” – consistently targeting police stations, politicians’ mansions, governmental buildings, banks, as well as food supply warehouses and pharmacies, to distribute food and vaccines. ‘Akkāwī, came to have several titles, classified as a “social bandit” by one sociologist (Seurat 2012:262), and labelled as a “Champion of Mobilisation” by another scholar (Lefèvre 2021:105). The masses hailed him as the Che Guevara of al-Tabbānè, but he was denounced as a thug to the officials. On the 16th of October, 1971, L’Orient-Le-Jour, a liberal newspaper, categorised the Organisation as a “neighbourhood gang” in an article titled “The group responsible for Tripoli’s explosions has been decapitated.” This headline was accompanied by news that ‘Akkāwī “was arrested after a confrontation” (102), and he was jailed for a second time. Three years later, in June 1974, ‘Akkāwī’s 10-year prison sentence was cut short as he died under “puzzling circumstances” (Assafir June 16 1974:8).

screen_shot_2024-11-12_at_1.51.52_pm.png

“5,000 mourners bid farewell to the leader of The Organisation of ‘Rage’”

(Assafir June 16 1974:1).

Ten days after ‘Akkāwī’s sudden death, a study he had written while imprisoned was published, illuminating the context behind those “puzzling circumstances.” “Most inmates,” he observed, “suffer from various ailments, particularly stomach illnesses and food poisoning, [...] and “are provided with pills from the prison’s pharmacy, but little else.” Even the only available means to earn money for the prisoners, through needlework and beading, is subject to the monopoly of al-Ma‘lūf [merchant]: “He sells 1 kilo of beads to prisoners for a price ranging between LL 20 and 30, even though its price outside is only 12 LL.” Additionally, “he sells 1 kilo of onions for LL 1, even though they are rotten,” similar to the “unwashed and unpeeled vegetables served in the prison.” “Like other prisons in Lebanon,” he remarked, it is “a living grave, an architectural masterpiece from the outside but a place where detainees are subjected to beatings and punishment for the slightest objections or infractions,” such as protesting “the lack of oil for weeks or signing a letter with the Lebanese Arab Republic.” “Even juveniles,” he added, “are treated as less than animals, packed into cells and subjected to cruel punishments if they break any rules. They are forced to run with their male body organs tied while being cursed and insulted.” He also hesitantly noted that only selected inmates “from a certain sect are exempt from this torment and allowed to spend the day outside the cell, assisting in administrative tasks such as censoring books sent to prisoners,” rejecting those considered “subversive,” particularly “communist books” (Assafir June 24 1974:2).

Reframing social crises as the handiwork of sectarian-socialist conspiracies from beyond the borders, as seen in the 1971 anonymous statement to the press on the Alawite neighbourhoods, is not a singular occurrence in Lebanese bureaucratic records. Farīd Shehab began his career with the French Police in Lebanon and by 1939 rose to Head of the Counter Espionage and Anti-Communism Sections. But he also maintained “an intimate relationship with the British” through collaboration with Colonel Coghill, head of the British Security Mission in Lebanon during the post-war independence (Hashimoto 2017:43). In 1947, he was trained at the Scotland Yard’s Superior Police Training College. Upon his return, he was appointed Head of the Sûreté Générale (ibid.). During his tenure (1948-58), he established an informant network that not only documented the organisational structure of the Communist Party (CP)8 but also personalised records of communists. Of the most extensively documented was Artine Madoyan,9 an Armenian refugee from Adana, and member of the Joint-Secretariat of the CP of Syria and Lebanon (Madoyan 2016).

Post-independence Lebanese bureaucrats, such as Michel Chīḥā who extensively contributed in the drafting of the constitution, viewed “two primary issues as overshadowing all others in the Arab world: Israel and joint defence” (‘Āmel 1989:220-221). In practical terms, they meant that the threats posed by jeopardising regional governance were as significant as Israel’s existence, which endangered Lebanon's interests. This led to calls for a regional alliance to confront the forces destabilising the status quo, particularly “communism,” which was perceived as a looming threat that compelled Arabs to defend themselves against its subversive potential, emanating “from the east” (ibid.). Therefore, the call for joint defence became a strategy to block the tides of communism in the post-Second World War era.10 By the early fifties, the Lebanese government had banned the CP, but even by 1953 the communists were still publishing and circulating clandestine newspapers, such as al-Ṣarkha [The Uproar] in Tripoli.

img_0433.jpg

al-Ṣarkha, seen here mourning the death of Stalin, 1953.

Building on Adam Hanieh’s Marxist conception of the state (2013), and as we have seen, the Lebanese state constitutes a site where contradictions within the society, and even within the dominant class, are solved to sustain capitalist accumulation and preserve dominion. By facilitating conditions favourable to capital, the state helps align the interests of individual capitalists, which might otherwise be fragmented. This requires a level of “relative autonomy” that enables the state to appear neutral but actually serving dominant-class interests. The separation between class and state, however, isn’t absolute; the state itself is an extension of class power, evolving as capitalist relations do. In contexts like Lebanon, state bureaucrats are embedded within the dominant class, illustrating this convergence in practice.

And, as demonstrated, with the expansion of global monopoly capital, the nation-state does not lose relevance; instead, its role intensifies as it manages the national capitalist order, thereby contributing to regional and global capitalist structures. An issue that underscores this dynamic is the “Northern Question” – a question that dates back to the creation of Grand Lebanon in 1920 and revolves around the identity of Tripoli and ‘Akkār as Levantine, Mediterranean, Lebanese, or Syrian.

At the onset of the French Mandate, ‘Abdulḥamīd Karāmī, a heir of an affluent and notable lineage, held a near-monopoly over the city’s political representation, despite the French attempts to counter his refusal to cooperate through various notables who opposed him (Ra‘d 2013:9-35). Meanwhile, French officials and commissioners were in dispute over whether annexing Tripoli and “the Muslim parts” of ‘Akkār had been a mistake (Traboulsi 2012:86). A way-out, suggested by Émile Eddé,11 was for Tripoli to become a “free city” under French control, granting Lebanese nationality to Christians and Syrian nationality to Muslims (ibid.:90). However, in the mid-1940s, a compromise had emerged, crowning Karāmī as premier as a manoeuver serving “the integration of Tripoli” in the nation. One of the early outcomes of this compromise occurred in 1945, when the Alexandria Protocol was set to be signed during an Arab League session that discussed Egypt’s proposal for a federal union project. At that time, Karāmī’s government, who had established his reputation as a Syro-Arab nationalist during the French Mandate, sought to influence the outcome through its foreign affairs ministry. Their objective was to reshape the Arab League from a federal framework into a guardian of the established Arab states, instead of supporting a federal union (ibid.:111-112).

In 1950, ‘Abdulḥamīd passed away, leaving his political mantle to his son Rashīd who emerged as a political advocate for Arab Nationalism. Despite viewing Arab unity as a means to counter the political dominance of Christian notables over their Muslim counterparts in Lebanon, he was too anxious about losing privileges to larger, more powerful Arab notables in the event of true unification. This paradox haunted many Lebanese Arab nationalist politicians, particularly as Arab nationalisation policies began to target Arab capital, not just foreign interests. Throughout the 1950s and into the 1970s, Karāmī manoeuvred his way into premiership across several governments, maintaining a dominant political position in the city’s political representation, a status that faced periodic challenges but remained intact until 1972. Nonetheless, although Tripoli’s politicians were making progress within Lebanon’s ruling consortiums, local sentiments continued to exhibit “separatist tendencies” (Lefèvre 2021:55).

The question of the “Lebaneseness” (or lack of) of Tripoli shows, once again, that the Lebanese state is not a static entity but a social relation between classes, structured to secure the interests of the dominant class. The “thugification” and quelling of leftist guerrilla organisations like The Organisation of Rage, whether in their capacity as workers or as militants, reveal the mechanisms through which the Lebanese state continues to operate until today. In Lebanon, this means to constantly (re)produce a sectarian monopoly capitalism, where both the superstructure and base are shaped by monopolistic tendencies, channelled through sectarian frameworks of distribution.

- 1. https://gulbenkian.pt/biblioteca-arte/en/read-watch-listen/construction-of-the-iraq-mediterranean-oil-pipeline/

- 2. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Land-use-map-of-Tripoli-Source-Prepared-by-the-author-based-on-the-1963-Master-Plan_fig8_44230807

- 3. al-Jabha ash-Shaʿbīyya li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn, founded in the wake of the 1967 defeat, is a Marxist-Leninist organisation created by merging the Movement of Arab Nationalists’ armed wing, the Vengeance Youth, with other former smaller guerilla bands.

- 4. Elyās Murquṣ (1970:12-13) lists more than ten factions in The Spontaneity of Theory in Guerrilla Warfare.

- 5. The Rogers Plan, proposed by the U.S. Secretary of State William P. Rogers, aimed to end the War of Attrition following the 1967 War through Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories in exchange for Arab recognition of Israel.

- 6. https://www.facebook.com/tripoliinblackandwhite/photos/a.337373399629792/921875354512924/

- 7. The Institut de Recherches et de Formation en Vue de Développement, a research group led by a French priest in 1960, was commissioned by President Fuad Shihab to assess Lebanon’s socioeconomic resources and needs.

- 8. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/structure-lebanese-communist-party

- 9. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/artine-madoyan

- 10. In 1954, a crucial component of this strategy took shape, laying the foundation for covert cooperation in “the fight against Communism and Zionism” within the Arab League, with involvement from Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and other countries (Asseily and Asfahani 2007:68).

- 11. Émile Eddé emerged in politics as a leading figure representing the “protectionist” tendency. His proposal encapsulates the essence of this movement, which viewed Lebanon as a Christian sanctuary. The more “extreme” vision sought the annexation of Christian Lebanon by France, while the “moderate” view aimed for French protection to safeguard Lebanon’s Christian population from being overwhelmed within the predominantly Arab region (Traboulsi 2012:82-83).

Asseily, Youmna, and Ahmad Asfahani. A Face in the Crowd: The Secret Papers of Emir Farid Chehab, 1942-1972. London: Stacey International, 2007.

Gilsenan, Michael. “‘Akkar Before the Civil War.” Middle East Report, 162 (January/February 1990). https://merip.org/1990/01/akkar-before-the-civil-war/

Ginzburg, Carlo, interviewed by Nicolas Weill. “Carlo Ginzburg : « En histoire comme au cinéma tout gros plan implique un hors-champ »” [Carlo Ginzburg: “In history, as in cinema, every close-up implies an off-screen scene”]. Le Monde des livres (October 3, 2022). https://www.lemonde.fr/livres/article/2022/10/03/carlo-ginzburg-en-histoire-comme-au-cinema-tout-gros-plan-implique-un-hors-champ_6144175_3260.html

Gulick, John. Tripoli: A Modern Arab City. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

Hanieh, Adam. Lineages of Revolt: Issues of Contemporary Capitalism in the Middle East. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2013. 1-18.

Harris, Lillian Craig. “China’s Relations with the PLO.” Journal of Palestine Studies, vol. 7, no. 1 (Autumn 1977), 123-154.

Hashimoto, Chikara. The Twilight of the British Empire: British Intelligence and Counter-Subversion in the Middle East, 1948-63. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

Imperiale, Alicia. “Perché Italia? Perché Italia…” Log, 53 (Fall 2021), 8-14.

Jabber, Fuad. “The Resistance Movement before the Six Day War.” In The Politics of Palestinian Nationalism, ed. by William B. Quant et al. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. 157-175.

Lefèvre, Raphaël. Jihad in the City: Militant Islam and Contentious Politics in Tripoli. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Merhej, Karim. “Paradise Lost? The Myth of Lebanon’s Golden Era,” ed. by Julia Choucair Vizoso. The Public Source (October 29, 2021). https://thepublicsource.org/golden-era-lebanon

Nasr, Salim. “Backdrop to Civil War: The Crisis of Lebanese Capitalism.” MERIP Reports, no. 73 (December 1978), 3-13.

Seurat, Michel. Syrie, l'État de Barbarie [Syria: The Barbarian State]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2012.

Traboulsi, Fawwaz. A History of Modern Lebanon. London: Pluto Press, 2012.

Ziadeh, Khaled. Neighborhood and Boulevard: Reading through the Modern Arab City. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

التميمي، رفيق، ومحمد بهجت. ولاية بيروت، القسم الشماليّ، ألوية طرابلس واللاذقيّة. بيروت: دار لحد خاطر للطباعة والنشر والتوزيع، ١٩٨٧. ٢٠٠-٢٦٢.

جريدة التمدّن. "القصّة الكاملة لدولة المطلوبين في طرابلس، ١٩٧٤". جريدة التمدّن (العدد السنويّ - ٢٠١٧).

جريدة السفير. "زعيم منظّمة الغضب يموت في السجن". جريدة السفير (١٦ حزيران ١٩٧٤)، ١، ٨.

جريدة السفير. "خمسة آلاف يشيّعون زعيم منظّمة الغضب". جريدة السفير (١٧ حزيران ١٩٧٤)، ٨.

عكّاوي، علي. "التعذيب والإهانات والاستغلال في سجن رومية". جريدة السفير (٢٤ حزيران ١٩٧٤) ٢.

رعد، ليلى. الاتجاهات السياسيّة والاجتماعيّة والاقتصاديّة في طرابلس ١٩٤٣-٥٨. طرابلس: مكتبة السائح، ٢٠١٣.

سبعين، خضر. "عندما أتى الموساد إلى طرابلس لاغتيال سعيد السبع". جريدة التمدّن (٦ تشرين الثاني ٢٠١٨).

سماحة، جوزيف. "التحرّك والقمع". جريدة السفير (٢١ آب ١٩٧٤)، ٧.

سماحة، جوزيف. “أصحاب الأملاك ورقيق الفلاحين". جريدة السفير (٢٠ آب ١٩٧٤)، ٧.

سماحة، جوزيف. “عندما اكتشفت الدولة 'سرّ' المشكلة". جريدة السفير (٢٢ آب ١٩٧٤)، ٧.

عامل، مهدي. مدخل إلى نقض الفكر الطائفيّ. بيروت: دار الفارابي، ١٩٨٩.

فخر، حسن. "صلابة الثورة الفلسطينيّة وتعزيز وتنظيم دعم الجماهير اللبنانيّة لها الضمان الأساسيّ لحرّيّة العمل الفدائيّ". مجلّة الحرّيّة، العدد ٤٨٩ (١٠ تشرين الثاني، ١٩٦٩) ٦-٧.

كمال، هيثم. "الانفجار الطبقيّ في عكّار". مجلّة الهدف (٢٨ تشرين الثاني ١٩٧٠)، ٨-٩.

مادويان، أرتين. حياة على المتراس. بيروت: دار الفارابي، ٢٠١١.

مرقص، إلياس. عفويّة النظريّة في العمل الفدائيّ. بيروت: دار الحقيقة للطباعة والنشر، ١٩٧٠.