We Raise Fists, They Shake Fingers: Remembering Feminist Revolutions

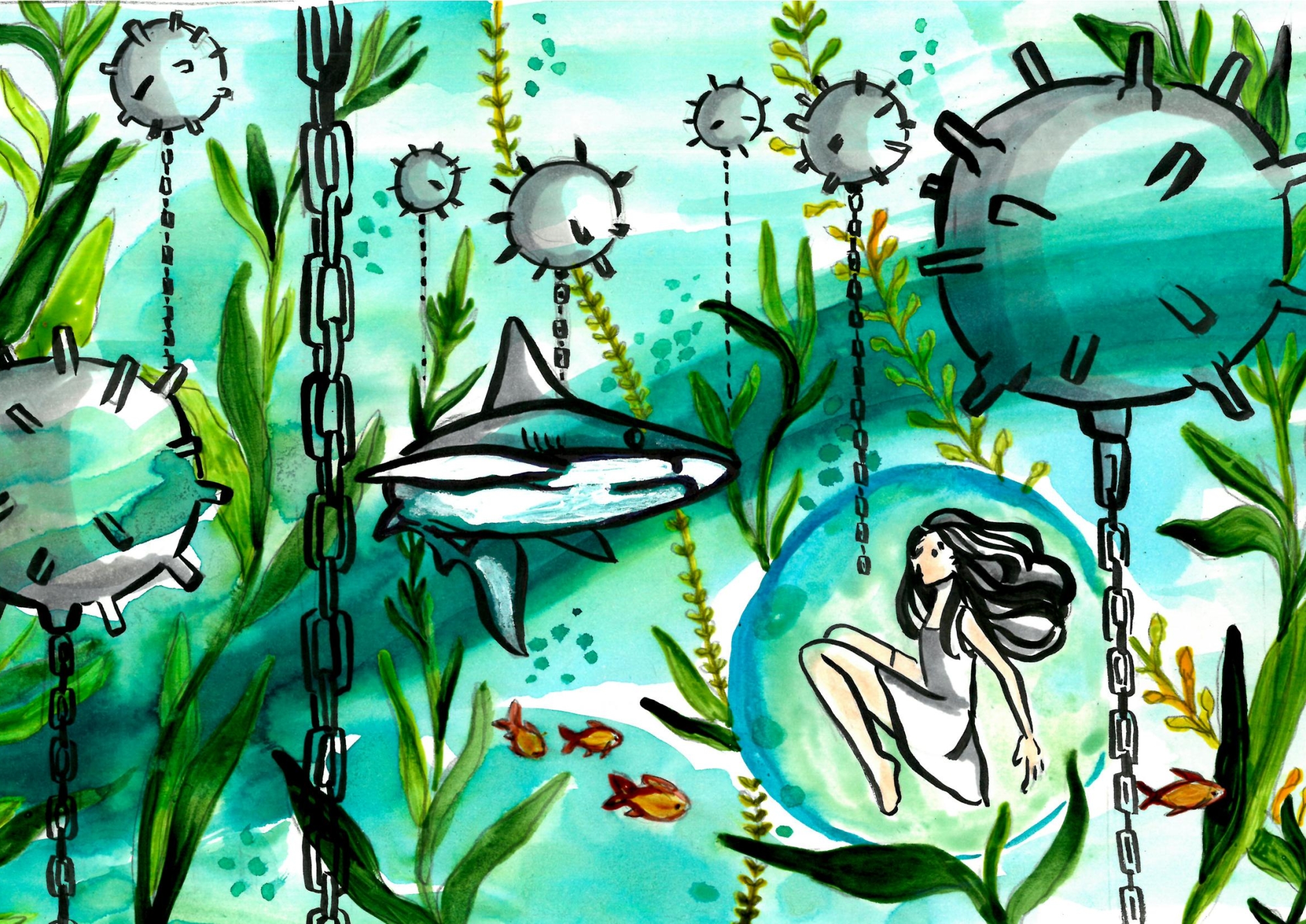

Bomb Field

In the early morning of Sunday, December 15, 2019, Raed Yaghi, a protestor, was beaten on the head by riot police in Beirut. As a result, he lost his memory. The physical violence was not exceptional; it has been routinely exerted by the state security apparatus against protestors in the geography of Lebanon since October 17, 2019. But a forced loss of memory against the collective awakening of the people, as many on the streets qualified the revolution to be, comes to signify gut-wrenching repression – a system that pushes its dissenters back into the unspoken, a collective blackout, an erasure of history from below. In this sense, collective awakening doesn’t have to do with waking up from slumber – we need not “wake up” to know our realities, but with a people that refuses to forget, that remembers as an act of resistance. So how to keep our collective memory alive, not only to service a far-away moment of history, but for us, for our revolutions, for our here and now?

We did not become revolutionaries. What’s more, we did not become revolutionaries overnight. We grew in and into revolutions, and they grew towards us. I was born in Beirut during the civil war, on a particularly difficult night; missiles fell from the sky like rain, and although I don’t remember, I dream of thunderstorms as bombs, and rubble and destruction. My grandparents were compensated in shares of disproportionately low value by Solidere for their house in downtown Beirut, and I still remember the taste of dispossession, the silent rage, in my grandmother’s milk cookies. In collectives we marched in the dark under torrential rain, knees deep in sewage water that overflows every winter, to scream feminism and liberation, and years later, we would find each other again in the streets of Beirut, shaken but defiant, the encounters suddenly carrying histories, and we would fall back into organizing together.

Revolting can disrupt authority, obstruct its course, refuse to conform. Revolting can also confront, rebel, and overthrow. To say that the revolution that started on October 17 within the Lebanon nation-state was a mere reaction to economic measures and cuts by the government would overlook how revolutions function. Revolutions are plural and plenty; they can be silent, and they can accumulate for years before they come undone. They are what we know in our everyday, in our lack of shine, in our banal. We deal in resources that are never sustainable – financial, human, affective; we are threatened with loss, and we end up worn down by economies of precarity and conditionality. So we grieve. Despair, rather than hope, is our revolutionary force. It is a revolt against apathy and oblivion. And it is hard not to take it personally, because it is personal, as it is relational and collective. A revolution is feeling uprooted but carrying on. A revolution is surviving the system so we can survive each other.

What we have seen since October 17 in the Lebanon nation-state, then, is but the physical manifestation of our many revolutions – their visible component. On many Sunday afternoons, I made my way through the crowded alleys of downtown Beirut, chasing memories that should have been my childhood’s. No longer Solidere’s ghost town, it came to life as al-balad, with lights, chants, street art, food stands, and second hand books. In the mornings, we would invariably wake up with apprehension, only to join the collective motion that no longer needed us to push. It felt like every act of resistance was conducive to this moment, our histories circling back into it. The revolution had its own time. Slowly, with the roads reopening and businesses resuming, the violence against protestors became normalized, and the timelines of our daily lives merged with that of the revolution. But how could we go back to normalcy when normalcy is the problem?

***

It is no coincidence that similar tropes are emerging across the Global South, igniting prolonged workers’ strikes, revolutions as we know them: gas prices hiking, local currencies plummeting, governments increasing taxes and austerity measures, banking systems serving the rich and restricting the poor, all resting on the backbone of rotten systems and governments that have sat in power for decades. It is no coincidence either that a neocolonial North would lean towards the extreme right, fearing foreign rebellions. But this is not a tale about North and South. It is about state- and bank-led economies that continue to neoliberalize and accumulate debt; it is about the hoarding of wealth by the few that depleted and sucked the majority dry beyond reasonable livelihood. When xenophobia will no longer be enough to keep “citizens” in check and explain away the lack of secure employment and access to resources and services, we will have to address the neoliberal market in its entire machineries – states, banks, industries, corporations. We realize that the system itself is not sustainable, that it is a matter of time until it collapses, and how could it not? But the cost we will bear will be colossal.

We need to start exposing the global scam that are banking systems. For the past few weeks, I and countless others have queued in banks for hours, only to leave with our cap of two to three hundred dollars in cash per week. We are asked to either deal with now highly taxed virtual transactions, or exchange our money for less, in the “official price” of the Lebanese Pound, when the market price of the dollar is skyrocketing. Practically, we are being robbed. And so, we need to start understanding nation-states as corrupt projects. The arbitrary borders that are supposed to fall and organize under autonomous jurisdictions end up being machines of discipline, control, and repression that perpetuate themselves by dividing people between insiders and outsiders, between “civilized” and the working classes, in favor of a delusional belonging to an authentic and “respectable” national identity. As feminists in perpetual revolutions, we speak from and about our contexts because this is what we know. This piece is no exception; I go back to images and examples from the ongoing revolution in the Lebanon nation-state. But I now wonder if this is what we are allowed to know. I am dreaming of organizing transnationally, across geographies, our revolutions liberated from the limiting scope of nation-states. How can we grasp this moment to organize across imposed borders, meant to keep us in check and under control? Erosion needs to happen at a global scale.

As a child, my parents shielded me from what they called politics. In terms of knowledge, nothing was off-limits, except the histories and realities of where I grew up. I realize it was a marker of middle class privilege. In a way, I didn’t have to be privy to any struggle beyond our own individual survivals. But I learned politics from the trivial and the everyday. With time, I unlearned respectability. It was a revolution.

The thing about respectability politics is that it only applies to dissenters, rebels, those who refuse to conform to the norm. Protestors are held to unrealistic standards of “civility.” They are policed for insulting their rulers. They are demonized for blocking roads. They are delegitimized for any demonstration of violence, be it fireworks, stones, or burning tires. Our rulers-turned-oppressors use the rhetoric of differentiating between peaceful, “respectable” protestors with tame demands, and rude, naughty, “uneducated” rioters, who are portrayed as existing in a vacuum of chaos for the sake of chaos. But beyond tear gas and rubber bullets, the violence of the system on our resources, on our livelihoods, on our bodies, is a daily war. No system has fallen by polite request. The logic of it is maddening: a government, corrupt to the extent of no longer being able to give its people their own cash money, disciplines its “subjects” for going outside the narrow confines of how and where and why they can protest. Their fingers, shaking at protestors in patriarchy that wants itself benevolent, in phallic warnings and threats and “look what you made me dos,” are met with raised fists, a feminist symbol of liberation.

***

We want revolutions to be moments where collective imaginaries converge and meet. We romanticize being on the streets in mass movements and protests, screaming and reclaiming and resisting. And of course, it makes sense: riding a wave that defies imagination by changing the landscape of what we know, materially and metaphorically, is a powerful emotion. We feel that we are transcending structures, so we believe we can wipe systems of oppression in our path. But when euphoria dissipates, when despair creeps up on us again, we must do the difficult work.

Revolutions are not grand acts. They are what remains when the grand acts are subdued. The performativity of the public sphere has everything to do with the problematics of visibility and their individualistic treatment. We forget those who cannot be on the streets because of their health, mental health, families, employers, or because they are burnt out and worn down. We forget refugees and migrants who share the claustrophobic confines of the nation-state but who experience it much more violently without the cushioning of national outrage, and for whom revolutions have different stakes. To remember them, it is not enough to spare them a thought; we must work to undo the structures we are complicit with, starting with the master’s tools: “Lebaneseness” and nationalism. And so, we must consider what and whom we are obscuring in the individualized acts praised as “heroic.” In the same vein, it is discourse that works on backbones and root structures, bringing about the possibilities of a common vision. The physicality of revolution, therefore, is a space to speak with and to, rather than speak at others, to organize with, rather than organize others.

Punctuated with tear gas and sirens, Beirut’s nights are organized in rows of militaries and masked partisans; protestors would keep emerging from behind the smoke, gaining ground and losing some. The system has broken the sanctity of its own military apparatus. Finally, we can talk about militarization and the police state. In recruitment stories, the military institution is, for many, the only outlet and work that have the legitimacy and backing of the state. Regional disadvantages and discrepancies play a big role in reinforcing this balance of power. Here is the caveat: nation-states coopt poverty, absorbing it in institutions that will protect their interests and keep the poor, poor, but with the additional accolade, short-term relief, and abstract national honor. The ruling class is, effectively, barricading itself within an infrastructure that does its dirty work. And so, we can only perceive the security state apparatus as a triad of ruling elite, police and military institutions, and informal supporters organized in militias (but not always operating as such), known as “thugs.” By keeping protestors busy via the violence of its apparatuses that diverts their attention from the core issue (the fall of the regime), the system that wants itself benevolent uncovers its true face of police repression.

How is the system still standing two months into a revolution that slowed its movement to the point of agony? To realize the magnitude of this monster machinery is daunting. So the question becomes: how we have gotten to this point? The ruling elite owns most of what we know, including all public institutions, some of which they privatized to maximize their profit. It is not enough for the government to fall, in its parliamentary structure and members. It is not enough for ministers to resign. Those are but accessory, almost honorary positions of power to an oligarchy that has festered. The image and standing of the za'im (ruler), on whom people’s livelihoods depend, is the foundation of the security state apparatus triad. When the zo’ama (rulers) accuse the revolution of causing the economic crisis, they are effectively portraying protestors as a threat to this livelihood, a barrier of flesh and bones between their partisans and their daily bread. Used to a system of wasta, which Maya Mikdashi calls an “economy of favors” in a yet to be published work, the za'im got too comfortable. The system is baffled by a people that refuses to go home; it is obsessed with wanting to negotiate with the revolution leaders; it raises fingers again, asking for communiques of demands. That a popular movement could organize from below with no clear leadership or strategic experts, that it would still persist despite the deployment of all possible strategies, is unfathomable to them. But how do we, the people, starve the system?

***

Negotiating reforms is a way of feeding into the system. My definition of reform is that of prioritizing the abolition, amendment, or passing of a law, policy, or structure, and making concessions in return, with marginalized communities becoming bargaining chips. This work has been spearheaded by a portion of civil society and the UN machineries, and although historically important, the landscape has shifted. We cannot and will not negotiate with the forces we seek to eradicate. Packaged as a “better than nothing” option, engaging in reform is a form of inclusion that keeps the system intact, but widens it just enough to serve the interests of the middle classes. In a way, reforms are a bourgeois project.

We need to do away with the figure of the za'im, vestige of the system, in our own communities, and experiment with novel ways of organizing. We are constantly threatened with politics of scarcity, by those in power, by their partisans, by the media, by a portion of civil society, and even, in some instances, by our own communities and selves. We are told that there are so few of us that criticism and disagreements are unproductive. But we are the many; we are everywhere; and we need to have those conversations.

It is in this spirit that this last minute issue of Kohl came to be, as an open space for documentation, giving space for contradictions and disagreements, and linking arms with the documentation efforts of others with whom we link arms in the struggle. A revolutionary archive is an archive with a memory. Our resources might not compare to those of the system, but our oppressors fear us because we remember beyond our individual selves; we remember collectively, across borders, across times, across histories. And memory is resistance and never-ending revolutions.