A Review of Jasbir Puar’s The Right to Maim (and additional interjections)

Cover Website.jpg

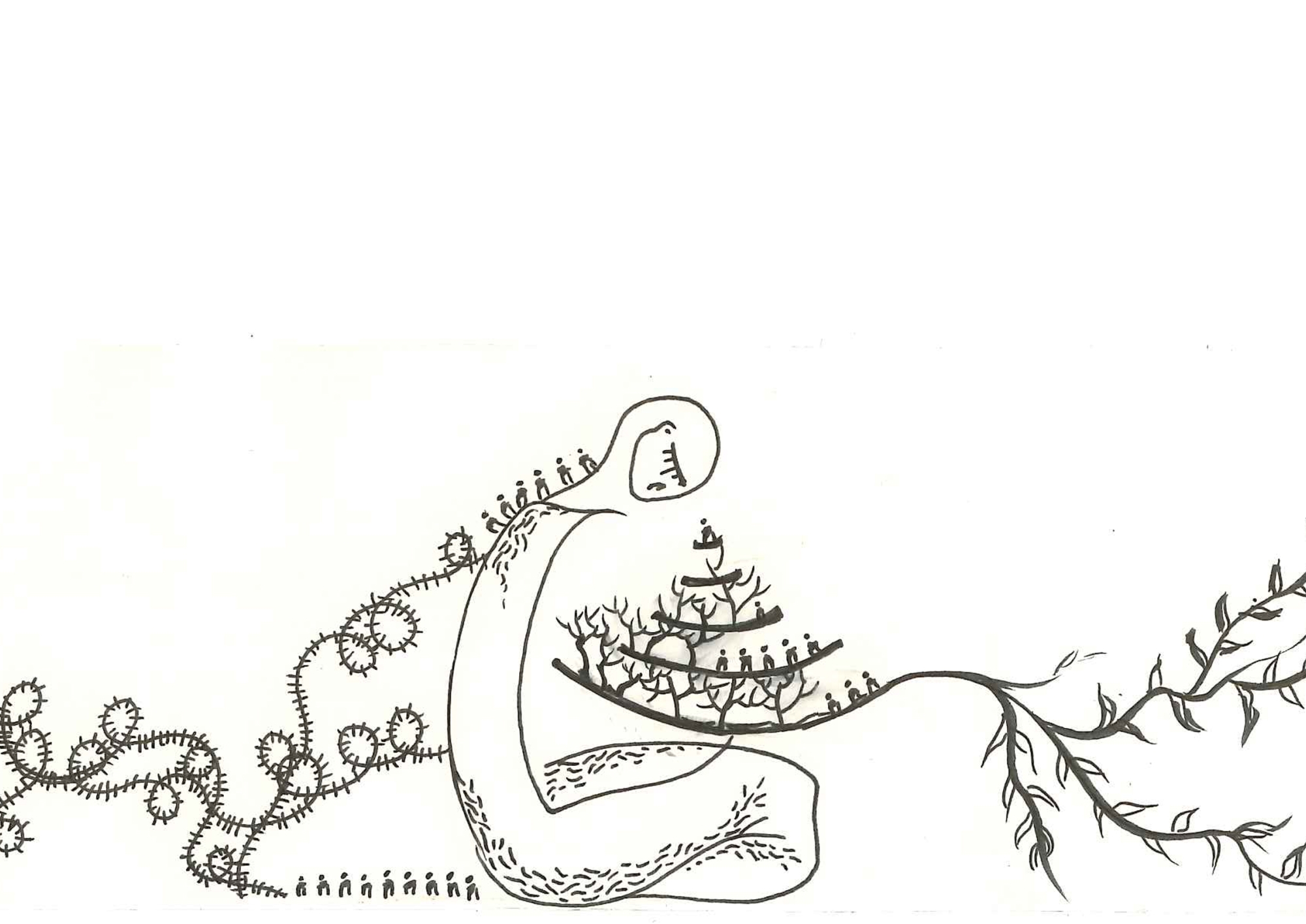

Illustration by Zeina Hamady 2018 ©

In the preface to her most recent work The Right to Maim, Jasbir Puar informs her readers that she mobilizes “the term ‘debility’ as a needed disruption … of the category of disability and as a triangulation of the ability/disability binary, noting that while some bodies may not be recognized as or identify as disabled, they may well be debilitated, in part by being foreclosed access to legibility and resources as disabled” (xv). In what follows, I offer an overview of Puar’s main arguments and supplement them with an applied example by drawing on Israel’s ongoing debilitating operation of Gaza.

Reading Jasbir Puar’s latest work is a draining affair, both intellectually and emotionally. The links she draws between seemingly unrelated contexts, including the “It Only Gets Better” affair, police violence against demonstrators in Fergusson in Missouri, or Palestinians resisting Israeli occupation are not directly discernible, even for the experienced reader. However, let it sink in, and what emerges is a thorough argument that leaves no stone unturned in its minute examination of the links between the body (both social and biological), biopolitics, liberal regimes, and neo-liberal practices. Such is the reach and scope of her analysis that it becomes easier for the reader to imagine the end of the world rather than the end of capitalism. This observation is not meant as an exaggeration; rather, it is the very point I am trying to make, and I urge the reader to bear with me at this stage.

Debility, as a model of governance, lies at the core of Puar’s analysis. Debility ought not to be used interchangeably with disablement, and Puar repeatedly reminds the reader that she uses the concept of debility to challenge the disabled/non-disabled binary. Whereas disablement “creates and hinges on a narrative of before and after for individuals who will eventually be identified as disabled,” debilitation “comprehends those bodies that are sustained in a perpetual state of debilitation precisely through foreclosing the social, cultural and political translation to disability” (xiv). Such a distinction, when applied to a Euro-American framing of disability rights, translates as follows: the before/after disabled/non-disabled narrative reiterates and reactivates a liberal framework that whitewashes disability rights. This is because questions related to recognition, empowerment, pride, or else are ultimately shaped by unequally positioned lives. As Puar puts is “… we will not all be disabled. Some of us will simply not live long enough, embedded in a distribution of risk already factored into the calculus of debilitation” (xiv). This reminder is crucial for appreciating the work of Puar. Misreading it could result in the conflation of debility with what Lauren Berlant terms “slow death,” understood by Puar as the “ordinary work of living on” (40) in a chrono-normative existence where our bodies are destined to fulfil particular tasks at particular times (for example, going to school, getting hired, finding a partner, reproducing, and so on) regardless of our preparedness.

Following Puar, for capitalism to subsist, life must be maintained through a logic of debilitation that keeps bodies in check all the time and down to their last molecule. Here, capitalism emerges alongside and is contingent upon the pitfalls of what Sara Ahmed terms “the promise of happiness” – a make-believe that highlights the racialized, sexed, gendered, and classed exclusionary processes that legitimize utopic fantasies of what the “good life” consists of. This point is elaborated in chapter 1, where Puar draws on trans-passing – the mechanism whereby transing bodies conform by passing as gender-normal as possible through a process of “piecing” together “separable malleable fragments” (45). We learn from Puar that the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) excludes Gender Identity Disorders from its definition. It thus negates the permanent debility of non-normative bodies, whose lives are largely shaped by hormonal injections, constant medical checks, and corporeal modifications. Ultimately, the ADA plays a direct role in the social and cultural capacitation of certain bodies and is thus geared towards the “normativization” (42) of who counts as disabled whilst ignoring debility. The magnitude of the ADA’s unwillingness to engage with debility is highlighted in chapter 2.

Puar dedicates chapter 2 to demonstrating the massification of debility by pointing out the unevenness of differentially-crippled1 populations vis-à-vis profit-making. The reduction of disability to an “accident” in mainstream rhetoric, including the ADA’s approach, “sublimates,” to borrow from Puar, the debility of entire populations: from trans bodies who are left permanently disabled following botched back-alley plastic surgeries, to Latin@s migrant workers who suffer physical injury on the job and lack medical insurance, or Palestinians who are intentionally maimed by the “might of Israel’s military” (x). Ultimately, Puar is pushing for a disability justice approach that is capable of “theorizing the biopolitics of disability and the biopolitics of debilitation” together by “[addressing] and [attempting] to eliminate the local and global conditions of inequality that give rise to the incidence of much – if not most – of the world’s disability” (67). In other words, a disability justice approach is less about personal grievances and more about the systematic structures that produce them in the first place: for one to claim their (disability) rights, they must be recognized as full citizens to begin with, which is not the case for purposefully debilitated populations.

The last two chapters of Puar’s work scrutinize the injustices committed by Israel on the Palestinian population by substituting a geopolitically-informed analysis for an all-encompassing post-humanist one – a deliberate approach, in my view, aimed at unsettling the ontological anxieties of the most ardent of Israel’s supporters. Puar demonstrates the biopolitical core of Israel’s infamous mechanism of Pinkwashing in chapter 3 and introduces the “right to maim” in chapter 4 in order to expand our understanding of classic biopolitics beyond Foucault’s making/letting live/die dichotomy.

That Israel has constructed itself on the basis of a “complex pronatalist agenda” (111) is well-documented in the literature. This agenda has informed Israel’s genesis and continues to. The promise of the Zionist homeland, in Puar’s astute writing, “[rehabilitates] the Jewish people from their seemingly disabled state in the Diaspora to a new healthy and ‘normal’ nation in Palestine” (102). Nowadays, Pinkwashing allows Israel to position itself as the only democracy in the Middle East. At the same time, we learn from Puar that the recognition of same-sex rights went hand in hand with an ever-growing reproductive technology industry2 aimed at countering the high fertility rate of two undesirable populations that offset the supposed harmony of the homonationalist Jewish nation-state, to name the ultra-orthodox Jewish, and the Palestinian Arab. Through carefully-crafted legislations and a politics of avoidance that cater to both the Israeli state and the religious authorities, we learn from Puar that Israel’s fertility industry is premised on and contributes towards the racialization of its natalist agenda. That is, certain foetuses are prioritized and seen as worthier than others.

Reproductive technology aside, Puar reminds us that the same neo-liberal economy that constructs Israel as a gay-friendly tourist destination is contributing to the increased NGO-ization of social work in Gaza. NGO work, however, is premised on the targeted debilitation of the Gazan population. By allowing foreign aid into Gaza, Israel presents itself as a fair player; it paints a defensive (against Hamas) strategy of its military might. Not only do we know from critical works on NGO-ization that for the largely marginalized, their immediate grievances and expectations do not always converge with donors’ priorities, but a political economy of “care” and rehabilitation with global reach also drives and sustains the outcome of maiming. The apparent just war that Israel deploys, i.e. debilitating, is reinforced by neo-liberal biopolitical profiteering that bases itself on the illusion of a good life sometime, somewhere, and the possibility of accessing it despite of disability.

The targeted debilitation of Gaza exceeds the making/letting live/die coordinates that inform classic approaches to biopolitics, notably Michel Foucault’s. On the surface, Puar’s work brings forth the works of Judith Butler on “livable” and “non-livable” lives (Butler 2006) and Cynthia Weber (2016) on “underdeveloped” and “undevelopable” bodies. However, the rendering of debility as a status in itself not only “triangulates the hierarchies of living and dying,” as Puar argues, it shows the continuum between two seemingly unrelated binaries and thus successfully shows the untenability of the juxtaposition of peace as the anti-thesis of war. If anything, the Palestinian population that is “available for injury is capacitated for settler colonial occupation through its explicit debilitation” (128-129).

It has been four months since I was first approached to write a review of Puar’s book. A lot has happened in Palestine since. In recent weeks, my Facebook feed has been swarming with photos of the late Ibrahim Abu Thurayya and the recently injured Aed Abu Amro. Abu Thurayya had lost both his lower legs in an Israeli strike on Gaza some ten years ago. On 15 December 2017, Abu Thurayya was shot and killed east of Gaza City whilst demonstrating against Donald Trump’s decision to move the embassy of the US from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Abu Thurayya was not a hazardous victim. Seen through the lens of Israel’s “right to maim,” Abu Thurayya rose against the limits that Israel’s debilitating policy supposedly imposes: lingering bodies with limited or no prospect of productivity. Israel’s killing of Abu Thurayya is not the natural progression from a tactic of merely maiming to one of killing. Rather, it is telling of the very anxieties that lie at the heart of the Zionist project: even the most crippled of Palestinians stands up to Israel. For the Israeli citizen whose sole claim to sovereignty is informed by the Israeli state’s mighty military, Abu Thurayya is a sight to behold. Such anxieties are equally captured by the maiming of Aed Abu Amro more recently.

Out of the innumerable Palestinians who are killed or maimed daily by Israel, Abu Amro was singled out on social media following overly sensationalised and romanticised circulations of his photo, taken on 22 October 2018 by Turkey’s Andalou Agency photographer, Mustafa Hassouna. Some compared Abu Amro’s photo’s aesthetics to Eugène Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People whilst others likened Abu Amro to David fighting Goliath, a metaphor in reverse that shakes the very foundations of the mediaeval roots of the Israeli nation-state’s claim on Palestinian soil. The overt fascination with Abu Amro is reflective of a world whose priorities are seriously questionable. We seem to quickly forget that there are no happy endings in the land of settler colonialism. There are no before and after moments of wiped-clean injuries, rehabilitated bodies, and state-of-the-art prosthetics. Abu Amro was shot weeks after his photo “trended.” He might not be dead, but he is certainly maimed. He is but one body in the endless supply of Palestinians that are readily available to be injured, time after time, in an open prison where hospitals are bombarded and nurses are deliberately shot. It makes sense, then, that we ask, alongside Puar, what kind of disability emerges in the face of a debilitating occupation?

The Right to Maim could be considered a paradigm-shifting work, particularly in the case of those disciplines that remain impervious to affective methodologies and epistemes. Not only does it contribute to existing debates within disability studies, trans studies, critical geography, and critical race studies – to name a few, it is another example of the success of assemblage as an analytical tool, since it is capable of putting in conversation seemingly unrelated events and bodies. Although the complex syntax and language of the book contribute towards narrowing its audience, it remains, nevertheless, an invitation for mainstream political science scholars to engage with the Israeli occupation of Palestine, albeit from a new perspective. Puar’s work pushes even the more experienced reader outside of the boundaries of their intellectual and activism-centred paradigms. Despite the bleak picture that she paints, it would be wrong to presume that she is merely pointing out the fallacies of the discriminatory structures that sustain our world as we know it. On the contrary, her analysis casts a light on previously undetected injustices, which, in its turn, calls for an ever more sophisticated analysis that is capable of drawing together intersectional and relational thinking in an increasingly post-humanist existence. Whether liberal self-styled activists will heed her call is another question. Such is the task at hand that the very translation of her observations into feasible work requires a full-time commitment, which is highly unlikely in an economy that absorbs much of our daily hours towards paying our bills. Still, her work is the all-embracing materialization of this very conundrum, whether we invest ourselves towards unknotting it or not.

- 1. Puar coins “crip nationalism” to explain how certain disabled bodies, largely informed by the potential of their rehabilitation or capacitation, i.e. profitability, work largely towards excluding those bodies who are deemed irremediable, to name permanently debilitated ones.

- 2. Puar reminds us that Israel is known as “the world capital of in vitro feralization” and has the “highest number of fertility clinics per capita in the world” (112).

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Berlant, Lauren. 2007. “Slow Death (Sovereignty, Obesity, Lateral Agency).” Critical Inquiry 33(4): 754-780.

Butler, Judith. 2006. “Violence, Non-violence: Sartre on Fanon.” Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal 27(1): 3–24.

Puar, Jasbir. 2017. The Right to Maim. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Weber, Cynthia. 2016. Queer International Relations: Sovereignety, Sexuality and the Will to Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.