BB and Me: A Review of Between Banat by Mejdulene Shomali

between_banat_landscape.png

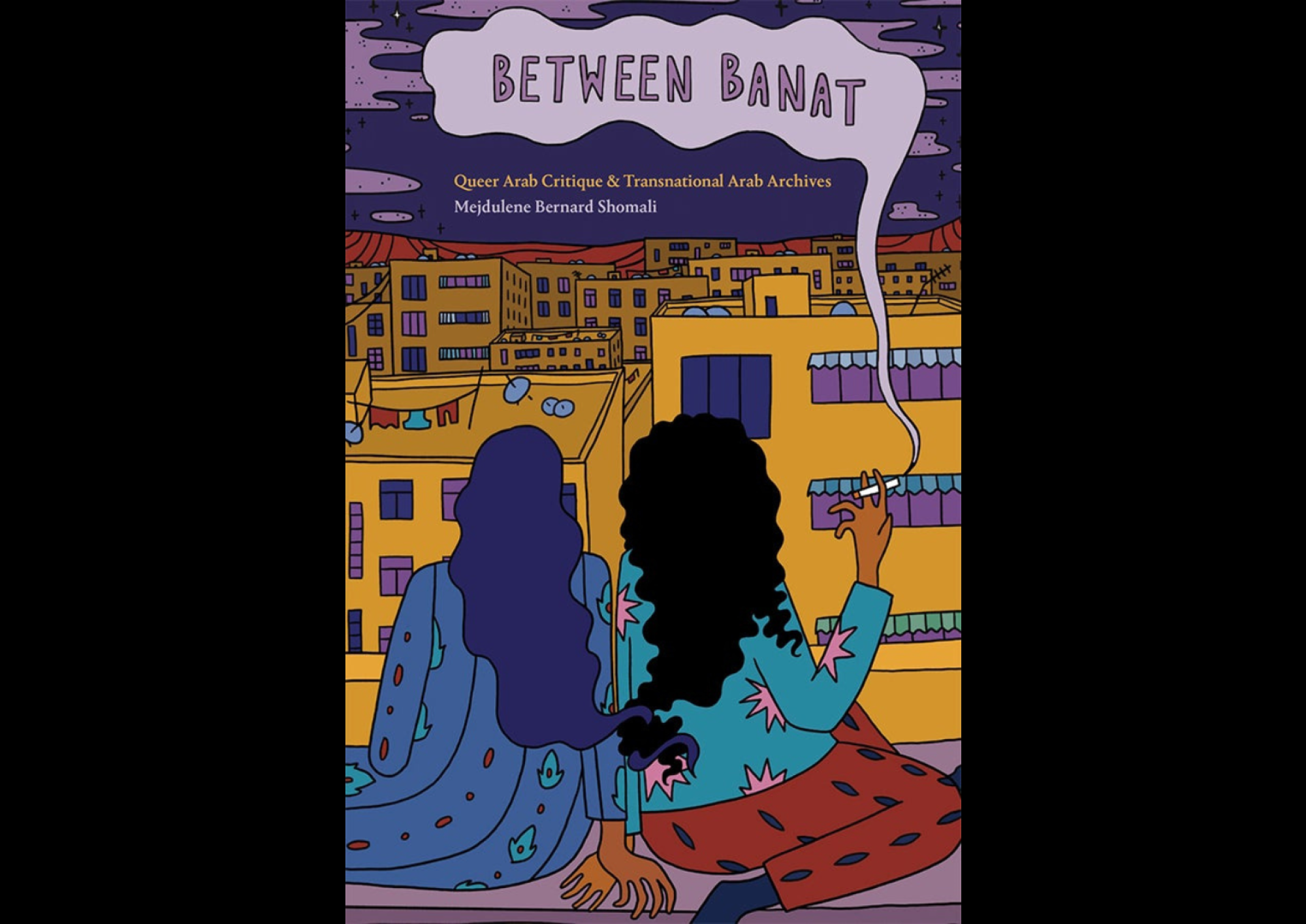

Book Cover Illustration by Audre Nasr (@ahlan.my.darlings)

https://dukeupress.edu/between-banat

I got hold of the book Between Banat: Queer Arab Critique & Transnational Arab Archives (Duke University Press, 2023) sometime in June 2023. Since then, I have introduced it to numerous peers, students, colleagues, acquaintances, and strangers in myriad spaces, some more likely than others, including an ER room in El-Koura (North Lebanon), and on one occasion, on a UK train.

Let’s start with its cover. Far from the abstract and at times confusing illustrations we have become accustomed to see on the cover of queer theory books, Between Banat’s (BB), by Aude Nasr, is an open, come-as-you-are kind of invitation. It shows the back of two bodies sitting on what appears to be a rooftop overlooking the city’s landscape at night. One is wearing trousers, the other a dress. Their long hair intertwines at the tip. The reader is left guessing whether their hands are touching or not, a visual clue which simultaneously troubling and comforting meaning can only be detected by those accustomed to reading against the grain (Chapter 3). Never had a cover spoken so faithfully to a book!

But the real comfort that BB brings is its timely release. Someone out there, to name our author Mejdulene Bernard Shomali, had been invested in a labour of political love that seriously rethinks some of our home’s ugly truths, notably Arab anti-blackness, the supremacy of Arabness across the so-called Arab world, and the tendency to homogenize women and men, to name a few. Every resource and archive that Shomali uses is dedicated towards re-assessing, and at times pushing to the limit, the lived implications of categories we often take and practise as given, including woman, Arab, or queer. As the book progresses, not only are these notions seriously questioned, some more comprehensively than others, they also emerge in permanent relation to and tension with each other.

In the opening sentence of the book, Shomali tells us that she is searching for queer Arab women ancestors (p.1). The starting point of Shomali’s archaeological undertaking is its rejection of framing queer Arab subjectivity as “a derivative or assimilationist version of the West” or as “a failed Arab subjectivity” (p.14). Whereas these recommendations have long constituted the cornerstone of our teaching and (un)learning(s) of the queer Arab subject, there was yet to be a comprehensive scholarly work capable of moving the conversation forward, a gap that BB successfully fills.

BB is a journey of queer Arab exploration that is continuously on a loop. Its journey is its very destination. This is evidenced by the fact that each chapter extends methodologically on its precursor, thus showcasing the analytical reach and scope of what Shomali terms Queer Arab Critique (QAC), the primary lens that informs her writing. In Shomali’s words, QAC is “grounded not in individual subjects, but in attentiveness to the ‘between’: desires between bodies, bodies between nations, words between languages, nations between one another” (p.2, emphasis mine).

By purposefully neglecting an analysis that centres the modern and presumably finite project of the nation-state, a global key player whose relationship to queerness is contested at best and deadly at worst, QAC paves the way for a queer pluriverse capable of transcending physical borders whilst attending to the spiritual, aesthetic, and affective dimensions of being. QAC is a learned position for effecting a transnational counter-politics that resists bordering – one with the potential of transforming our present chaos-world into a whole-world community, to borrow from postcolonial scholar Édouard Glissant (1997).

Aware of the size of the task ahead, Shomali guides her reader through five carefully crafted chapters where an abundance of archives, including felt1 ones, are minutely examined against the background of Orientalism and what she terms “heteronationalism” (more on this later): from English and Arabic novels by Arab-American and Arab women authors in chapters 1 and 3 respectively, to two feature films from Egypt’s golden era in chapter 2, to autobiographical accounts of queer Arab women in chapter 4, ending with queer feelings in chapter 5. Opting for banat2 instead of the more conventional “queer Arab woman” terminology allows Shomali to turn our attention to the “many subjects [who] occupy femininity as a subject position in order to reject and resist heteronormativity” (p.14), and to “reconsider our understanding of femininity as a counter to masculinity that reifies the gender binary” (p.18). Banat as a context-specific working notion that dilutes gender binaries is a much welcome intervention. Whether Shomali has explored its full disruptive potential in her first monograph, however, remains open to debate. Still, what we have here is a well-developed tool that constitutes a new trajectory in the study of gender in relation to the so-called Arab world.

Chapter 1, where the main task at hand is the identification of the many discourses that impede the fulfilment of queer Arab representations in Arab-American literary productions, is my favourite. Although the chapter does not address queer desire per se, it does an excellent job of situating the harm done by “heteronationalism” on all bodies that deviate, be them migrants, people of colour, or non-conforming embodiments. To this end, Shomali juxtaposes and contrasts various Arab-American women authors’ attempts at de-orientalising Scheherazade, the quintessential Orientalist femininity figuration in western imagination. These authors, themselves minority ethnic (Arab) subjects that must navigate discourses of supremacy and assimilation, heteronormative structures, and state violence, end up unwittingly reproducing them. This epistemic glitch on a loop allows Shomali to show how the spectre of the “good Arab migrant” acts as a catalyst for the crystallization of an elitist and exclusionary “heteronationalism.” Instead of confronting the postcolonial condition that underpins Arab migrants’ experiences, notably racialization processes back home and in the US, the authors that Shomali examines opt for the safer and less emotionally charged notion of “cultural authenticity,” whereby the postcolonial Arab subject is relegated to a depoliticized and “pure” precolonial Arab status (p.142). Although Shomali does not refer to it as such, the analysis on offer shows the full potential of what she coins “queer spectatorship” (Chapter 2), a mode of reading against the grain capable of pinpointing discursive erasures.

Chapter 2 is an ode to the golden era of Cairene cinema, this time with a queer twist. Shomali reads two feature films using “queer spectatorship” wherein the “viewer reads the film against the heteronormative central plot and actively refuses the dominant narrative in favour of fleeting moments and ephemeral gestures that are by definition insignificant or secondary within the overall film” (p.64). Though rife with visuals and narratives exuding female homoeroticism, both films end on a heterosexual “high” (marriage). Here, the queer subjects’ full emergence is impeded by the rationale of marriage, one of heteronationalism’s most privileged institutions.

Chapters 3 and 4 is where the queer Arab subject speaks. In them, Shomali examines Arabic novels (all of which have been translated into other languages) and queer autobiographical accounts, respectively. Shomali strategically selects the contexts of Lebanon, Syria, and Saudi Arabia for her novels to challenge homogenic accounts of Arabness, queerness, and queer Arabness. Unsurprisingly, none of these novels offers closure per se, on par with their protagonists’ continuous journey of self-exploration whilst they navigate economic hardship, sexual violence, or racialization, depending on their position. Shomali draws on Linda Tuhiwai Smith to conceive testimony as a form of epistemic justice (p.123). These testimonies confirm previous works3 that sought to show how naming one’s sexuality is a complex negotiating process wherein direct translation (from English to Arabic), transliteration, and neologism coincide, and that the use of each is dependent upon the situatedness of the queer subject in question. Chapter 3 troubles the too-often muffed topics of Arab anti-blackness and disability by insisting on a “relational” understanding of Arabness to “foreground racialization and to consider Arabness without reifying anti-Blackness” (p.9).

Does the queer Arab subject ever fully emerge in Shomali’s work? Perhaps not, given the textual nature of the analysis on offer. Perhaps yes, for those who are well versed in queer spectatorship by virtue of their very existence. Either way, seen through the lens of sahq (Chapter 5), the queer Arab subject is yet to be. Following Shomali: “We must establish and engage in transnational collectivity; we must reject gender and sexual respectability; and we must reject authenticity politics, both precolonial and heteronational, as the defining metrics of Arab identity” (p.140). These are big asks that recall the blurred lines between scholarly and activist work. At the same time, Shomali’s focus on banat at times obfuscates masculine identities, and those women who do not ascribe to configurations of “banat,” let alone the role and place of men and masculinity – broadly speaking – in the larger futurity-oriented trajectory of QAC.

On the precise topic of the usage and limitation of archival analysis, Shomali reflects: “Between Banat [is] both a recuperative gesture, a reading against history to make history, and at the same time, a worried contribution to the archive it imagines” (p.5). Indeed, imagination is firmly tied to knowledge-production in Shomali’s work, and is part and parcel of the recuperative scope of QAC. Here, recuperation serves as a point of entry for young Arab queers who refute fetishist and neoliberal erasures of their politicized trajectories. At the same time, recuperation, thanks to imagination, serves towards a cathartic end for past-gone queer ancestors, to Shomali’s (and her readers’) relief!

BB might not be the immediate answer for policy makers and legislative impasses, but for those of us who have long committed to queer futurity, it is a reminder of the importance of thinking differently. BB’s dense writing and literary tone are reminiscent of queer scholarship, whereby un-layering and scripting one’s life into the text are part and parcel of writing. In the classroom and beyond, the physical use of the visuals and archives mentioned in the texts will undoubtedly contribute towards making accessible the complexity of the analysis on hand.

Ultimately, BB achieves its bi-directional promise of “longing for queer Arab women’s historical and future company” (p.3, emphasis mine). Inshallah! The tomboy in me lives. My neighbour’s ever-taunted hyper feminine son smiles. To our taytahs (grandmas), whose assertiveness eclipses every male elder in the house. To the statuesque belly-dancing drag queen from Beirut who can beat Superwoman with a single eye lash, with or without mascara. To our younger sisters who (almost always) have it easier. To the domestic migrant worker’s blingy attire on her day off. To our male cousins who had no option but to play with dolls from time to time. To our fathers who reckoned with their interiorised misogyny upon the birth of us daughters. To our mothers’ self-effacing existence in the name of our wellbeing. We love you. We are you and you are us.

Georgis, D. (2013). The Better Story: Queer Affects from the Middle East. New York: State University of New York Press.

Glissant, E. (1997). Poetics of relations. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Million, D. (2009). Felt Theory: An Indigenous Feminist Approach to Affect and History. Wicazo Sa Review, 24(2): 53-76.

Mourad, S. (2013). Queering the Mother Tongue. International Journal of Communication, 7: 2533-2544.

Shomali, M. B. (2023). Between Banat: Queer Arab Critique and Transnational Arab Archives. Durham: Duke University Press. https://dukeupress.edu/between-banat