Reproductive Justice as a Collaborative Framework: Working Through Assemblage

Cover Website.jpg

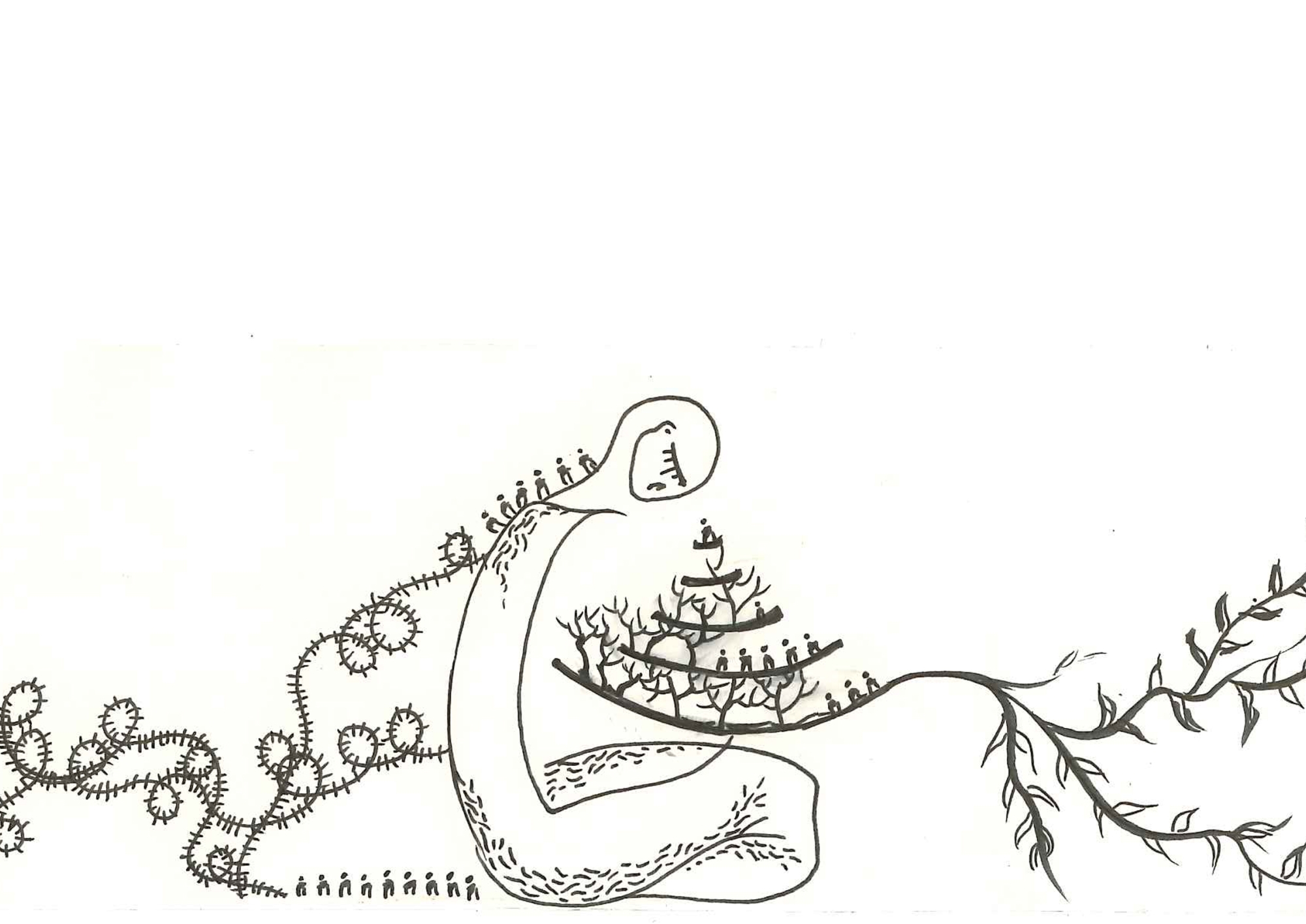

Illustration by Zeina Hamady 2018 ©

Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) is not only a matter of terminology. Despite its emergence from a place of struggle, it has been assimilated into mainstreaming practices that adopt a rights-based approach and discourse. It conveys, therefore, historical influences that take their root in UN processes, states’ monopoly over bodies, and the privatization of resources and care. By shifting the conversation to that of individual “agency” and responsibility, such practices do not take into consideration systems’ accountability and structural barriers. While reports and statistics about reproductive rights abound, there isn’t enough work on systemic injustices, and struggles become disconnected from one another, invested in immediate gains and self-promotion. Reproductive justice, therefore is not a mere lens; it is recognizing that issues and movements are indivisible and working towards dismantling injustice from its roots.

A collaboration between Kohl and the A Project, this issue is an attempt at bringing reproductive justice home. It starts with the premise that structures of violence need to be starved; one way to do so is to refuse to legitimize certain lives at the expense of others’. What does reproductive justice look like in non-western contexts? How do our lived experiences become theory that travels and shapes discourses? How and why do we make knowledge – ours and that of our communities – legible and accessible? How do we bring back the political in fields that claim neutrality and objectivity? These are but a few of the questions this issue grapples with. Instead of sanitizing processes in favor of “success stories” and images of harmony, it doesn’t shy away from points of rupture. But most importantly, it gives us, editors, authors, contributors, translators, and readers, hope in our ability to translate our imaginaries into histories in the making.

Medical Patriarchy and Institutionalization

The issue opens with Islam Khatib’s “Diagnosis: Chronic Patriarchy,” in our Artivism section. Featuring an illustration on medical patriarchy of the author’s creation, Khatib’s text is acerbic in its criticism of the medical practices that normalize their meddling with women’s bodily image and autonomy. With a hint of sarcasm, she takes a jab at doctors who give standardized recommendations in fields that are not their own, and deconstructs the purported “objectivity” of the field of medicine, exposing its patriarchal roots.

While Khatib makes the links between medical patriarchy and women’s bodies, Kate Hashemi connects it to its treatment of trans* bodies in Iran, in a research article titled “Divergent Identities in Iran and the Appropriation of Trans Bodies.” Medical patriarchy in that case serves the interests of a religious status quo: the widespread gender-affirming surgeries in Iran are used to “correct” sexual behavior, conflating gender expression, desire, and orientation, and to maintain the binaries of sex and gender. What Hashemi also highlights is the instrumentalization of trans* issues by women’s rights advocates: their parodying of transness in media and film ultimately renders them complicit with the system in place.

Medical patriarchy, institutionalization, and complicity are but a few elements that impede reproductive justice – a framework that is explored at length in an article titled “In the Pursuit of Reproductive Justice in Lebanon,” co-authored by Rola Yasmine and Batoul Sukkar. If medical patriarchy invisibilizes reproductive injustice, state institutions normalize such practices. In that sense, Yasmine and Sukkar offer us an intervention in the field. Not only do they historicize reproductive justice, but they contextualize it as theory and praxis, rooting it in the geography known as Lebanon. They then proceed to detail how reproductive justice weaves into different struggles, calling on feminist activists to understand injustices as systemic rather than operating in silos. Despite linking broader struggles and macro structures together, they do not overlook the stories of lived experiences and realities.

Imperialism and Global/Local Policies

In “‘Women’s Empowerment,’ Imperialism, and the Global Gag Rule,” Arianne Shahvisi shows how economic policies put into motion by imperial powers can still, to this day, affect the livelihood of women across the globe, particularly the Global South. One such policy is the Global Gag Rule; reinstated by Trump, it restricts women’s access to abortion because of its aid conditionality. The current form of neo-imperialism comes in the shape of monetary subventions from northern countries to different parts of the world. Perceived as charity and “aid” instead of restitution, it comes with strings attached and forces organizations to make difficult choices. The silence of the “women’s empowerment” discourse, picked up by corporations as well as NGOs, becomes complicity that is disempowering to women’s bodily autonomy and their reproductive justice.

But new forms of imperialism do not have to be global to restrict women’s choices; in fact, they can take the form of hegemonic policies and population control, as shown by Luna Saadeh’s “The Israeli Occupation and Palestinians’ Right to Choice in Marriage.” In the case of Palestine, freedom of mobility becomes a reproductive justice issue: the decimation of the land into cantons, areas, and different authorities, and its fragmentation by checkpoints, residency rules, and permits makes it impossible for Palestinians to live wherever they desire in their own land. Consequently, they cannot choose a partner/spouse from a different area without facing great bureaucratic hurdles and being separated from their families. Settler colonialism, therefore, employs reproductive control as a tool for ethnic cleansing.

Further complicating the binary of east/west and colonizer/colonized also entails dealing with spaces of rupture and ambiguity. In a political essay that theorizes personal experience, Menna Agha documents her difficulties with and opposition to the English terminologies that describe her body. “Female Genital Mutilation, Cutting, or Circumcision? Perspectives of a Nubian Woman” demonstrates how women’s bodies are subjected to multiple layers of violence. They are controlled by local discourses and narratives of female “purity” under the guise of traditions. At the same time, they are appropriated by global perceptions that are disconnected from the same bodies they seek to claim for their own benefit. Most poignant are Agha’s unsuspecting discovery of “voyeuristic” content that are meant to represent her, her narration of Nubian history, entangled with her own, and her journey into reclaiming sexual pleasure. She is not afraid to ask difficult questions, even when the answers are not straightforward.

Motherhood and Women’s Role

In “I’m Not a Mother, Therefore I Don’t Exist,” Shereen Abuelnaga traces a journey of her own that is distinct from Agha’s, but that resonates with its labor of archiving and problematizing the fixed roles and expectations women are subjected to. Abuelnaga’s description of her relationship with her mother is reminiscent of Sara Ahmed’s image of the willful daughter, personified by Abuelnaga’s “stubborn” body. She challenges the notion that women can only be complete if they have children of their own. A literary tour-de-force, the essay maps the struggles of different women across temporalities and geographies who defied society’s conventions when it comes to the expectations of motherhood. From De Beauvoir’s “dutiful daughter,” to Mernissi’s “harem girl,” to Rich’s “woman born,” Abuelnaga draws transnational parallels with younger Egyptian authors and poets, such as Iman Mersal and Sara Abdeen, and ultimately, with her own self.

Motherhood and the idealism and “sanctity” that shroud it make for Imene Amara’s anger in the opinion piece titled “The Trap of Ideal Motherhood.” Amara looks into historical moments to attempt and find an origin to the myth of ideal, instinctive motherhood. A form of labor that is assumed to be the exclusive responsibility of women, it remains mostly unrecognized and essentializes women’s roles and place socially and economically. Amara notes that in the eyes of the state, women’s needs and desires are secondary to that of their children; their contribution is reduced to providing “good” subjects to the nation.

Amara’s outrage is echoed by a soon-to-be working mother’s “Thoughts on Pregnancy.” This anonymous testimony, written by a pregnant woman, bemoans the never ending expectations thrown at women: daughters, wives, mothers, and workers, they are asked to prioritize their pregnancy on the one hand, but warned against “displeasing” their husband and not attending to his need. Any act of non-conformity is disciplined, shamed, and silenced, and feelings of guilt become the norm. The anonymity of this testimony is no coincidence: a woman cannot freely express her frustration with motherhood, her husband, her family, and society without backlash and intimidation.

Violence Dissected

Medical patriarchy, imperialism, and compulsory motherhood are all forms of violence linked to reproductive injustice and perpetuated on women’s bodies, and the bodies of gender non-conforming individuals. The multi-layers of violence are identified and named in the literary pieces of this issue. “The Woman With a Scar” is Imen Yacoubi’s gripping (short) story of Mariem, a woman whose stillbirth unfurls a series of events that make different forms of violence more salient. She is subjected to medical indifference, neglect, societal pressure, and an abusive husband. The scar, result of a C-section, parts her in two, effectively bringing out two women in her. Despite the clear loss and grief that haunt the story, it is ultimately a tale about the motions of rebellion and survival.

As for “Examination: Four Stories Inspired by Actual Events,” Reef Al-Amine and Sara Abu-Zaki open windows on to the lives of four different women, and the ways in which they are “examined,” scrutinized, and exposed. A young woman experiences her first invasive gynecologist visit. A middle-aged woman goes through an unnecessary hysterectomy at the recommendation of doctors. A mother is left to grieve a child she never wanted. An old woman reflects on the non-consensual abortion she was put through.

Violence feeds off women’s resilience; the expectations of strength and endurance from survivors overlook the structural and systemic violence they are subjected to. This is Theresa Sahyoun’s message in “You reap what you sow,” a sentence women often hear, especially when they are at the receiving end of sexual violence and harassment.

Disrupting Boundaries

The breadth of this issue covers grounds that must be documented. From grassroots knowledge to personal experience as political, it provides a basis for further research and historicizing of reproductive justice in the Middle East and North Africa. This does not negate our political duty to ask different questions, and push for discourses we want to see. This is exactly what Roula Seghair does in “Poverty Porn and Reproductive Injustice: A Review of Capernaum.” She ponders on the horizons the movie could have extended into had it named the systems of (reproductive) injustice, rather than catered for a liberal consumerist gaze. In her “Review of Jasbir Puar’s The Right to Maim (and additional interjections),” Sabiha Allouche maps the ways in which disciplines and frameworks are shaped by affect. Puar links queer necropolitics with disability, and Allouche adopts this trajectory by thinking through its intersections with current debates. Ultimately, what this issue tells us is that the assemblage of reproductive justice itself is as disruptive as our political and feminist imaginaries allow us to go.

But disrupting boundaries on the level of discourse cannot be contained by published texts or research or legible forms of knowledge alone. Collaborating with the A Project on this issue was, by itself, a disruption and challenge to the processes of knowledge-making, including our own. It is but another kind of coming together, of organizing, of exploring nodes of convergence, dissonance, and chaos (assemblage). It allowed us to materially explore some of the questions we have been asking for years. How do feminist collaborations take shape? How do we work through the notion of “ownership?” And how do we deal with the messiness of new avenues? The political value of this collaboration lies, to a certain extent, in imagining possibilities and building movements with accomplices who, like us, intentionally remain outside of the mainstream. Joining forces becomes, then, a political act, especially when we refuse to monopolize resources under the umbrella of one institution because of our belief in their just distribution. In that vein, our archiving labor can only take root in the communities that aliment it, and in collaborating with other non-academic, non-institutional groups, so that praxis and theory no longer exist in a binary – where praxis becomes theory in the making, and theory, a praxis of its own. We hope, one day, to document the process of coming together as feminists, with its moments of euphoria, dissonance, and complicity.