Anticolonial Feminist Imaginaries: Past Struggles and Imagined Futures

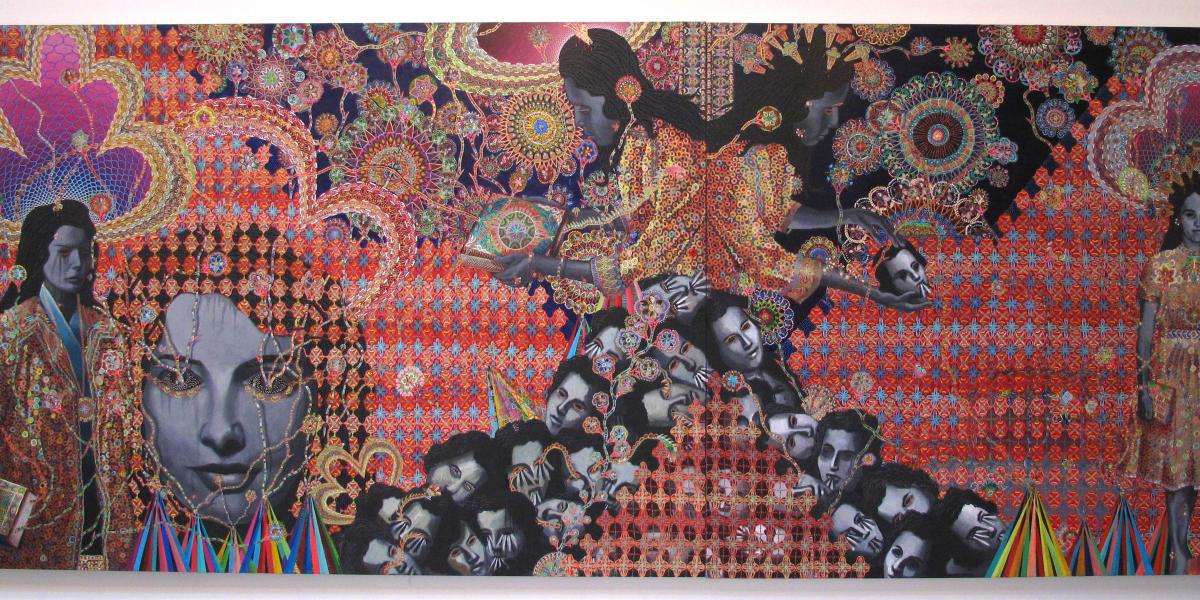

les_femmes_d_alger_20_60x144_2012.jpg

Les Femmes D'Alger, 2012

I am so tired of waiting,

Aren't you,

For the world to become good

And beautiful and kind?

Let us take a knife

And cut the world in two-

And see what worms are eating

At the rind.

- Langston Hughes

This special issue aims to interrogate and reimagine the location of gender and sexual politics in anticolonial revolutionary struggles. This project builds on the exciting and important scholarly work, literary writing, and archiving projects that have emerged to document and explore the question of anticolonial feminisms, which remains under-represented in broader questions of anticolonialism, twentieth century politics, histories of the left, and scholarly work on revolutions. We therefore imagine this as a contribution to the rich body of work focusing on marginalised, subaltern, and radical knowledges, movements, and figures, as well as to what thinking about anticolonialism from feminist spaces can tell us about past, present, and future.

From Pan-Africanism to Eastern European socialism; from contemporary Palestine, Iran, and the Philippines to indigenous struggles for sovereignty; how might thinking with and through gender and sexual politics shift the frame of what justice, freedom, care, and hope look and feel like? How might revolutionary pasts and revolutionary presents speak to feminist knowledge, and how might the radical futures imagined by those involved in gender and sexual politics tell different stories about familiar spaces, structures, and events? For instance, how might we complicate understandings of women’s positions either as nationalist heroes or as victims, bringing out nuances often left out from such debates? How might the long history of feminist re-imaginings of concepts such as freedom, sovereignty, community, care, sexuality, socialism, and more tell different histories of anticolonialism?

There is no denying the significant role played by feminists in anticolonial struggles and in contemporary activism. However, beyond tropes of courage and heroism, victimhood and betrayal, lies a complex story that brings together experiences of hope and its ultimate betrayal, stories of conformism and rebellion, contestations over the place of nationalism, and debates over the continuing role of patriarchy within the left. Put differently, what does it look like to chart unknown futures from feminist spaces?

Speculative conversations

In a recently published piece, Naghmeh Sohrabi (2022: 546-547) notes that

writing revolution as if women matter requires us to shift our analytical framework away from revolution as intellectual work (primarily located in the imaginings of revolutionary strategists and theoreticians) to revolution as political work (primarily located in action and in the streets), and in doing so bring to the fore the kind of epistemological reckoning that expands what counts as revolutionary history, and what counts as valid methods, sources, and interpretation.

In the spirit of this provocation, we start our special issue with a section called Speculative Conversations, whose aim is to both fill in the blank spaces of histories of revolution, and also re-imagine and re-capture lost, unheard, and erased voices. Here we draw on Saidiya Hartman’s (2008: 16) notion of “speculative” histories, as a method and ethos that seeks “to tell the stories of those who left no record of their lives.” Elsewhere, Hartman comments (2018: 467) on the unnoticeability of “revolution[s] in a minor key,” namely those acts of insurrections that do challenge and push in fundamental ways hierarchies of gender, race, and class, and structures of oppression, but that are unnoticed and largely un-recorded. Their unnoticeability is linked to the actor’s “wayward” positioning in the system, marginal both to the dominant and the dominated structures, and thus outside of the purview of what Sohrabi (2022: 549) called “the heroic prism” on which representations and histories of revolutionary thought and action rely almost exclusively.

Salma and Jeyran’s piece “The Long Road to Liberation” provides that opening for our special issue both as a speculative history and as a mapping of “an existent territory with objective coordinates,” as Saidiya Hartman (2008: 9) would have it. Conceived as an exchange of letters between each other, the authors reflect on the politics of history-making and the place of women in the Dhofar Revolution, and its larger implications for conceptualizing the role of women in projects of national liberation and revolutionary social transformation. Mai Taha’s and Sara Salem’s contribution centres a novel by Sonallah Ibrahim, Dhat, made visible via Latifa al-Zayyat’s review of the novel, published in 1992, and translated now by Mai and Sara from Arabic into English. Their translation is annotated in handwriting with their own thoughts and questions, and sometimes small sketches, providing a contemporary echo to “the figurative realm of an imagined past” (Hartman 2008: 9). Rana Barakat brings in the voice of Audre Lorde to reflect on questions of liberation and emancipation in Palestine. Lorde’s insights into anger and oppression, love and liberation provoke us to think about the political (mis)uses of rage in the Palestinian struggle. Hanna Altaher’s intervention opens with a personal vignette about Youssef Chahine’s Jamila, the Algerian (released in 1958). The figure of Jamila prompts Hanna to reflect on the limits of anticolonialism, feminism, and freedom, especially when assembled as an aspirational horizon, but also when set against the politics of gendered citizenship in postcolonial Jordan.

Feminist Methodologies

In Unthinking Mastery, Julietta Singh invites us to think through what it might mean to let go of mastery as a way of relating to the world. Focusing specifically on anticolonial thought, Singh suggests that colonial ways of knowing continue to be present in the form of attempting to master a given subject, field, self, or realm of knowledge. Singh has explored this in other pieces of writing, troubling dichotomies that continue to structure academic writing such as rational and objective knowledge versus emotional and felt knowledge. A commitment to forms of knowledge that push against binaries such as this one animates this special issue, where we are particularly interested in how we might produce forms of knowledge that engage multiple ways of knowing. This particular section, feminist methodologies, speaks directly to the possibilities of knowing, researching, and writing otherwise, centring poetry, pedagogy, and intimacy as central to knowledge production.

Maru Pabón has translated three poetic articles by Leila Baalbaki, a significant Arab writer who was the first to think through the condition of Lebanese women through existentialism. The themes of freedom, the female body, individualism, political betrayal, and many more thread through Baalbaki’s oeuvre and the three poetic translations, producing a window into the political and gendered setting of the late 20th century. Khaoula Bengezi similarly focuses on the poetic, specifically the folk poetry of women like Fatima ‘Uthman and Fatima Mahmood in Libya. We learn not only about ‘Uthman’s poetry, but more broadly about time and temporality, freedom and justice, and the question of who is read as an anticolonial figure from the vantage point of the present. Shane Carreon’s piece on poetic voice and trans writing in the Philippines explores how the poetic voice can embody both the singular and communal experiences and sensibilities of the self. Through a reading of poems they have written over the past decade, Carreon centers notions of world travelling and archipelagic thinking in order to reimagine what anticolonial thought looks like in/from the Philippines today.

For many of us, pedagogy has been an important entry point into broader questions of anticolonial liberation. In a piece on teaching decolonial feminist theories, Aytak Dibavar opens with the question of what it means to find hope in the face of utter defeat, thinking from the space of the classroom. Positing the classroom as a space of collective thinking and dreaming, Dibavar asks what it means to let go of mastery and to embrace unlearning, reminding us that radical vulnerability is central to feminist pedagogies and feminist knowledge cultivation. In “Talking ‘bout a revolution” Katherine Natanel, Kanwal Hameed, and Amal Khalaf collectively explore the entanglements of different disciplines with colonial forms of power. Focusing specifically on the “word” and the privileging of the written, they ask how other forms of script, such as land, body, breath, spirit, and sensation, can tell other stories.

Archiving past struggles

In her essay “History without documents,” Omnia El Shakry asks what it means to think about histories of decolonization in the face of securitized state archives and the broader absence of archives that might tell us stories of anticolonialism. Taken alongside the Eurocentrism of colonial archives, we are confronted with the question of archiving more broadly, and what it means to search for anticolonialism in archives that were not created to tell these stories. El Shakry calls on us to centre other forms of archives, such as letters and memoirs, that hold histories that are otherwise not considered part of more institutionalised archives. Here the intimate becomes important once again, as we can hear the stories of leftists, women, and other groups of people not usually seen as producers of historical knowledge. This section of the special issue speaks to the broader question of archiving past struggles, with each contribution telling a story of feminist revolution and resistance. By focusing on figures and movements that were central to resistance in the past, we see how different forms of archival knowledge can be mobilised in order to tell anticolonial and feminist stories of political change.

Ayesha Latif starts us off with a piece on the Punjabi poetess Piro Preman (1832-1872), attending to how autobiography and memoir are crucial spaces in which women tell the stories of their own lives. Through the traditional Punjabi poetic form of the Kafi, Preman tells the story of how she resisted Muslim, Turk and Hindu forms of power in order to produce a form of knowledge that worked against patriarchal retellings of history. In “No Longer in a Future Heaven,” Alina Sajed similarly troubles the binary of women as a historical force versus women as victims of history to ask instead how revolutionary hope can act as an alternative framing in relation to the position of women in anticolonial struggles in Algeria and Palestine. Thoughtfully unpacking “the woman question” in different times and spaces, Sajed attunes us to the haunting spectre of hopes and desires that take on a life beyond us, speaking to Langston Hughes’ question, what happens to a dream deferred? Zeyad El Nabolsy also touches on this question in his contribution on women’s liberation in the discourse of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde and the revolutionary writing of Amílcar Cabral. El Nabolsy contends that the emphasis on women’s liberation found within this movement is a consequence of Cabral’s modernist philosophical orientation and in particular a commitment to autonomy. This contribution highlights the importance of centring the commitment to gendered liberation amongst movements dedicated to anticolonial freedom, so that we can better understand the dreams deferred that Sajed references. Elisabeth Armstrong similarly turns us to the future in her piece on Esther Cooper and Vidya Kanuga, both committed communists and anticolonial/anti-racist activists. Armstrong highlights how past struggles were often both locally-driven and internationalist, while attuning us to the rich possibilities that existed in solidarity and struggle.

Contesting the present

We cannot honor the vibrant echoes of past struggles without paying close attention to how they reverberate into the present. We now turn to Thomas Sankara’s (1988: 376) heartfelt interpellation in his speech on the International Women’s Day in March 1987:

Comrades, there is no true social revolution without the liberation of women. May my eyes never see and my feet never take me to a society where half the people are held in silence. I sense the rumble of their storm and feel the fury of their revolt.

The urgency of Sankara’s call three and a half decades ago remains as contemporary as ever. It also speaks to the gap between desire and reality, between an anticolonial horizon of promise, hope, and dignity, and a reality of continued oppression, marginalization, co-optation, and complicity. This gap takes us to the heaviness of the deferred dream. It also prompts us to ask questions about the content of liberation: if liberation was the desired goal of anticolonial struggles, whose liberation did it ultimately posit and desire (Sajed [forthcoming])? With what consequences were women told to wait for their deferred dream of liberation in the hope of a later fulfillment? Can any meaningful liberation be a single-issue struggle? Audre Lorde’s (1984: 138) answer to this question is unambiguous: “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” The question and the answer allow us to re-visit the meaning of liberation as an aspirational horizon but also as a lived-in experience. Audre Lorde (1984: 51) draws out the assumptions behind a limited and incomplete vision of liberation and invites us to sit with the implications:

The supposition that one sex needs the other’s acquiescence in order to exist prevents both from moving together as self-defined persons towards a common goal. […] This kind of notion is a prevalent error among oppressed peoples. It is based upon the false notion that there is only a limited and particular amount of freedom that must be divided up between us, with the largest and juiciest pieces of liberty going as spoils to the victor or the stronger. So instead of joining together to fight for more, we quarrel between ourselves for a larger slice of the one pie.

What content does liberation continue to have in the context of the postcolonial state, obsessed with power consolidation, security, power-politics and steeped in a neoliberal present (Salem 2020)? And if the echoes of past struggles, with their betrayals, hopes, victories, and defeats continue to seep into the present and shape its course, how do we contest our present?

Nayrouz Abu Hatoum and Razan Ghazzawi pick up these last two questions and invite us to hold together both what Derek Gregory (2004) called the colonial present of imperial intervention and domination, and the violent practices of the postcolonial state. Their analysis looks at the politics of cooptation and weaponization of the Palestinian and Jawlani (Syrians in Jawlan) struggles for self-determination and liberation on the part of Syrian state officials as a way of justifying their mass human rights violations since the uprising in Syria, a practice they call “sumoud-washing.” The invitation-provocation to hold together both the colonial present and the violence of the postcolonial state also lies at the heart of Aytak Dibavar’s reflection on the rise of the movement woman, life, freedom in contemporary Iran. Drawing on decolonial, queer, anti-racist, and anti-imperialist perspectives, Dibavar challenges the reader to move beyond a narrow and myopic frame assembled by liberal feminist, white saviourist, and self-titled anti-imperialist readings of current protests in Iran.

Fania Noël’s essay “Paris is Burning” picks up the challenge to attend to multiple forces and yearnings, and re-positions the debate around intersectionality through an Afro-feminist lens. Noël discusses the intellectual and political circulation of intersectionality in French activist circles by tracing the history of anti-racist organizing in France and thus of the various antagonisms among diverse feminist currents championed by women of colour. Aida Hozič’s contribution opens with another invitation: “What does it mean to be a feminist in an unwanted colony, a place deemed unworthy of territorial conquest or even integration into a European polity, yet too dangerous or unstable to be left alone?” Speaking from the space of the Balkans, Hozič interviews Hana Ćurak, a sociologist and artivist from Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, a feminist meme-blogger, and the creator of a multimedia project “It’s All Witches” – “a platform for identification and subversion of patriarchal particularities in the everyday.”

For our concluding piece, Sara Salem interviews Rosalba Icaza, who is a Professor with the International Institute of Social Studies at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. The interview explores the limits of gender as a lens and challenges us to think whether gender/sexuality are not inherently colonial categories. Icaza indicates the centrality of Indigenous perspectives and struggles to the idea of pluriverse, which she conceives as a form of praxis that allows for the multiplicity and co-contemporaneity of lifeworlds and struggles. Ultimately, to Icaza, decoloniality is “a liberatory praxis [that] points at an ethics of relational accountability.” Taken together, the contributions in this special issue invite us to ground ourselves into a present where the power of coloniality endures in multiple forms, but where new configurations of power and new contestations complicate both the political terrain and the stakes entailed. Implicit in these readings, and indeed throughout the special issue, is also an invocation of a different future and of alternative horizons, intuitively sensed as possible and proximate, yet deeply contested and fought over in the present.

El Shakry, Omnia. “History without documents: The vexed archives of decolonization in the Middle East.” The American Historical Review 120:3 (2015), 920-934.

Gregory, Derek. The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell), 2004.

Hartman, Saidiya. Lose Your Mother. A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux), 2008.

Hartman, Saidiya. “The Anarchy of Colored Girls Assembled in a Riotous Manner.” South Atlantic Quarterly 117:3 (July 2018), 465-490.

Lorde, Audre. “Learning from the 60s.” In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press), 1984.

Lorde, Audre. “Scratching the Surface: Some Notes on Barriers to Women and Loving,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press), 1984.

Sankara, Thomas. “The Revolution Cannot Triumph Without the Emancipation of Women.” In Thomas Sankara Speaks. The Burkina Faso Revolution 1983-1987 (New York: Pathfinder Press), 1988.

Sajed, Alina. “‘Claim No Easy Victories:’ On the Political and Ideational Content of Liberation.” International Politics Reviews (forthcoming).

Salem, Sara. Anticolonial Afterlives in Egypt: The Politics of Hegemony (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 2020.

Singh, Julietta. Unthinking Mastery: Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements (Durham: Duke University Press), 2017.

Sohrabi, Naghemh. “Writing Revolution as if Women Mattered.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 42:2 (2022), 546-550.