Rethinking Intersections, Rethinking Contexts: Writing in Times of Dissent

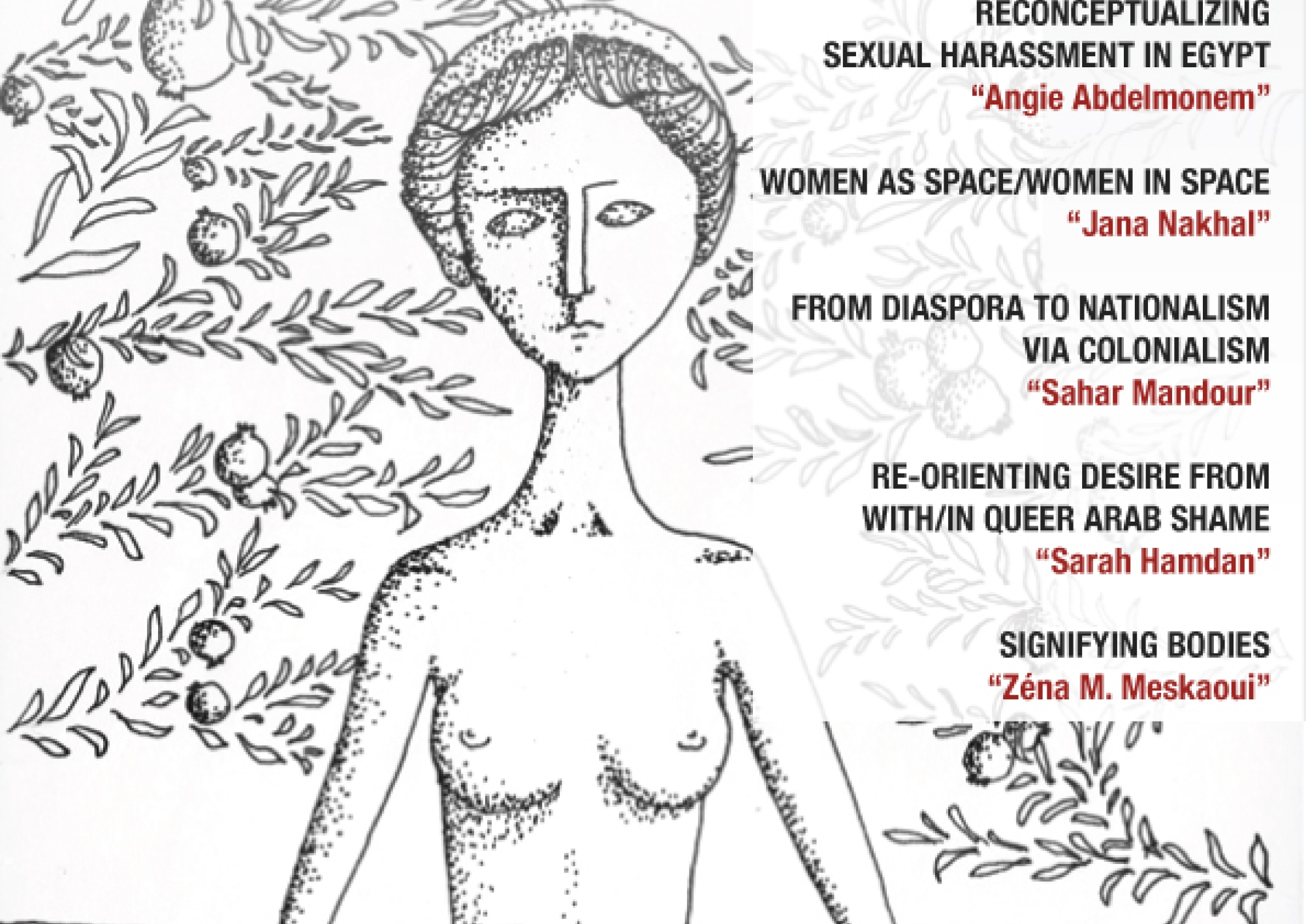

issue-1-cover.jpg

Speaking of a feminist knowledge production in the Middle East, South West Asia, and North Africa region is a daunting task. It has become increasingly difficult to centralize our knowledge production(s) in terms of location and definitions. Burdened with problems of access to information and lacking the tools to participate in the epistemological processes, our feminist movements struggle with the structures of domination and hegemony of knowledge in the MENA.

Many of the discourses around gender and sexuality in the region create a sense of exceptionalism when dealing with local feminists, queer women, and LGBT identities, especially when they intersect with other “marginalized” identities. We are automatically perceived as challenging or transgressing the status quo. While this might or might not always be the case, a plain reading of what local communities do or should do reflects a very narrow vision of the tropes of gender and sexuality in our countries. Ultimately, we watch ourselves being written off as the extras in our own stories, and our struggles hastily dissected to illustrate a ready-made argument. However, knowledge proper to our contexts or sensitive enough to account for our intersecting struggles is not too far from reach. It is simply relegated to the second place and often written out of multiple mainstream narratives, be they local, international, academic, or even civil society’s narratives.

Now more than ever, and with the wave of neoliberalism, imperialism, and religious extremism sweeping through our region, feminist writing is of unprecedented urgency. The dynamics of power located in the histories and influences of Western colonization in the region are not enough to justify the epistemic injustice faced by our rising feminist and sexuality movements. We need to write as a moral duty to the underdocumented movements that have preceded us, and as a strategy of resistance to counteract the binary of the imperial West vs. the extremist “Middle East,” and the indiscriminate universalization of the human rights discourse.

Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research is one alternative platform that has been conceived following a careful consideration of these challenges. When we speak of bodies, we are also tackling torture, fundamentalism, and bodies in migration. We are extending our definition of everything bodily to detention, confinement, refugee camps, hunger, and art. Far from reducing people and affect to their bodily functions, we are considering how those bodies – our bodies – represent themselves and are represented, and how they move in space and ideology. If the word “feminism” comes with its own set of westernized epistemology, “sexuality” has been automatically linked to identity. The articulation of “body” would, therefore, encompass a broader expression of sexuality.

Kohl’s first issue, “Rethinking Intersections: A MENA-centered Definition of Gender and Sexuality,” does not pretend to provide conclusive answers to the abovementioned tensions; rather it hopes to contribute with an open space of discussion and redefinition from within. The surprisingly high number of submissions we received as a response to our call for papers were representative of various academic disciplines and writing genres. The overwhelming majority of the articles featured in this issue are written by students and activists from the region. Collaborating with them on their writings and thinking through their concepts and arguments together have been a humbling experience for Deema Kaedbey and myself. Their tenacious will to write and be heard has inspired us beyond measure.

The issue opens with Arianne Shahvisi’s commentary on “Feminism as Global Imperative in a Globalised World.” Shahvisi’s passionate opinion piece deconstructs the type of neoliberal equality our globalized world calls for, and sheds the light on liberal assimilationist feminism, or what she calls “bullshit feminism.” She then draws the broad strokes of the feminization of labor, and the devaluation of caregiving, which both lead to the outsourcing of caregivers and domestic workers within a globalized system of intersecting racism and inequality. Shahvisi uses the outsourcing of migrant domestic workers as a case in point to demonstrate her argument, as she advocates for a moral imperative to be endorsed by feminism.

While Shahvisi tackles the space of the globalized economy as the scene of her focus, Jana Nakhal sheds the light “Women as Space/Women in Space” in the heart of the city Beirut. For Nakhal, “Relocating our Bodies and Rewriting Gender Space” entails a careful consideration of the capitalist and patriarchal economy. The literal configuration of urban spaces surrounding feminine bodies, including architecture and urban design, emphasizes and feeds into a gendered hierarchy. In that case, spatial identities redefine notions of femininity and masculinity and polarize the redistribution of private, semi-public, and public spheres.

If Nakhal’s article brings into focus the gendered inequalities embedded in the Beiruti configuration of space, Angie Abdelmonem recontextualizes sexual harassment in the public space of downtown Cairo in “Reconceptualizing Sexual Harassment in Egypt: A Longitudinal Assessment of el-Taharrush el-Ginsy in Arabic Online Forums and Anti-Sexual Harassment Activism.” Abdelmonem assesses the shift in Egyptian discourse around taharrush, the Arabic word for sexual harassment. The use of el-Taharrush el-Ginsy instead of the adopted “sexual harassment” highlights the ways in which language translates into our conceptual definitions of sexuality, abuse, and assault. Abdelmonem redefines this concept by rethinking through the signifiers of our own language.

With “From Diaspora to Nationalism via Colonialism: The Jewish “Memory” Whitened, Israelized, Pinkwashed, and De-Queered,” Sahar Mandour taps into the redefinition of intersections by expanding our concept of queerness, queering, and de-queering. Queering becomes a synonym for destabilizing existing structures of normativity, narrativization, and memory transmission. She transposes it to the Palestinian land, where the memories and histories of Middle Eastern Jews, Palestinians, and migrants are “de-queered” in favor of a single-axis narrative of Jewish memory and diaspora. The whitewashing of “Pink” oppresses all manifestations of queerness, and the threat it could posit for a Zionist state and ideology.

From a different perspective of queerness, Sarah Hamdan grapples with queer Arab subjectivities by providing a reading of Joseph Massad’s “Gay International.” By stressing on the plurality of (homo)sexualities, she walks us through the notions of queer affect and sexual difference in the context of Arab queer articulations of language and sexual identities. Her sharp analysis of Bareed Mista3jil: True Stories aliments the deconstruction of queer shame and hybridities, and resists the binaries rooted in Western hegemony and the categorization of sexual identities.

Taking a stroll back to war-torn Beirut, Zéna M. Meskaoui brings us full circle in the configuration of this issue’s articles. Her “Signifying Bodies: Artistic Representations of Embodiments in the Works of Samir Khaddaje, Rabih Mroué and Lina Saneh” is a careful reading of the artistic works and performances of Lebanese artists Samir Khaddaje, Rabih Mroué, and Lina Saneh. By juxtaposing different forms of artistic embodiments together, she reflects on the civil war and post-civil war eras from an artistic perspective. Meskaoui’s piece opens up new possibilities of rethinking gender representations artistically, and without solely focusing on the feminine and the masculine.

In addition to this issue’s research articles, our activists’ testimonies open a space of alternative writing and participation in challenging the status quo of publication, who gets to write about movements and activism, and in what forms.

In “Pinkwashing: Israel’s International Strategy and Internal Agenda,” Ghadir Shafie offers us a poignant testimony of her experience as a queer Palestinian woman living under occupation. With a firsthand account of pinkwashing, Shafie wittingly dismantles this vicious Israeli strategy by reflecting on “fitting in” and narrow definitions of sexual identities that do not recognize her intersectional struggles as a Palestinian. On the other hand, Ilham Hammadi assesses the current situation of women’s rights in Iraq, in her testimony “Women’s Rights in Iraq: Old and New Challenges.” Hammadi accounts for the degradation of the situation of women post-2003, and the response of feminists to such a drawback. She lays out the laws that regulate all aspects of women’s lives, and walks out through what it means to be a woman living in Iraq in light of recent geopolitical wars and changes.

With the aim of challenging the adopted modes of knowledge production, “Openings” provides a space of conversation for feminist activists. The recorded discussions are transcribed and edited, with the approval of all the participants. For this issue, “Openings” features the first part of a conversation among five young feminist activists who have closely worked together, and that was facilitated and edited by Sanaa H. The six participants beautifully interact together by sharing their perception on the concept of “movement” with openness and honesty. Finally, the issue closes with Anass Sadoun’s “The Bill on Fighting Violence against Women in Morocco: Anything New?” who details the clauses of the bill on gender-based violence in the context of Morocco.

Remembering that Kohl did not come out of a vacuum is of utmost importance. The concept behind such a journal is deeply engraved in the historical and contemporary feminist and leftist movements in Lebanon and in the region. Without intending to idealize our movements, Kohl is the product of collective thinking and feminist praxis. This first issue endeavors to feed into the visions and dreams of our many feminisms. If there is one thing we have to always remember in our work, I hope it is honoring that debt.