In the Dark Alleys of Translation

image_50355457.jpg

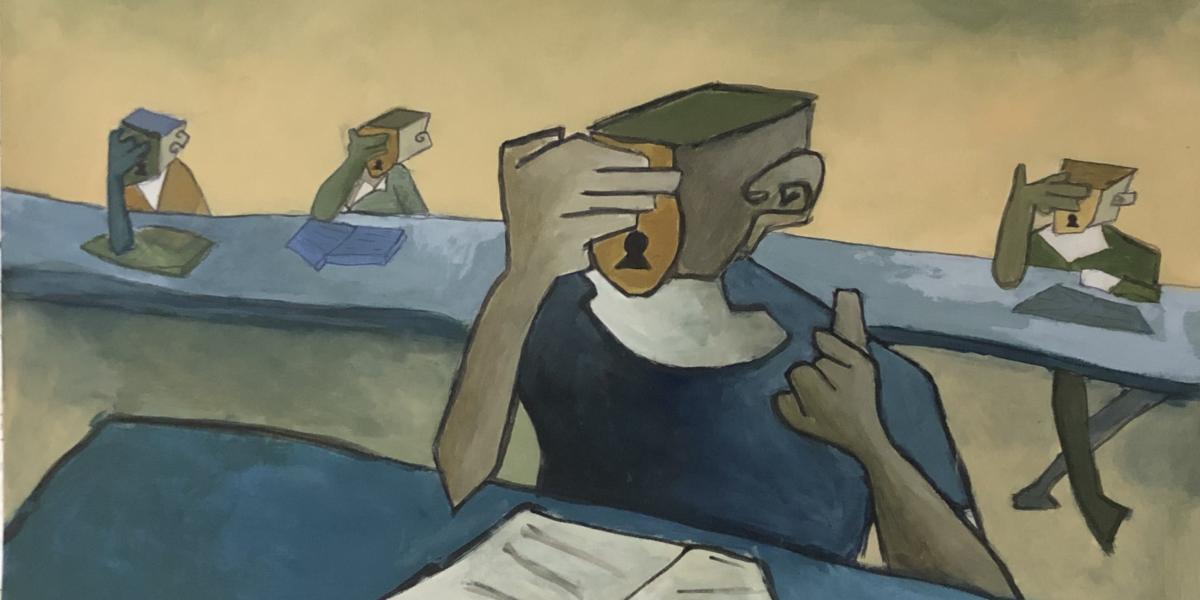

I don’t know how to begin this article, for I have never been asked as a translator to contemplate the act of translation. I practiced translation as a profession by chance, for reasons that are purely financial and life-sustaining. Thinking about what translation truly means has always been on the margin of my professional and daily life. I never indulged in such thought except fleetingly in the course of daily life humor and witty banter. I did not attend a college campus where I was asked to dive into the history of this profession and uncover the narratives of my occupational predecessors. Even if I had, those narratives wouldn’t have had an earth-shattering influence on my life: the archived history of translation doesn’t know anything other than the biographies of the elite philosophers (mostly patriarchs) who traveled the world, crossing lands and authorities, to dig up an expression or a formula or an epic text that changed the face of the world, which they then attributed to themselves. I am an Arab woman, daughter of the exclusion of a refugee society; of travel, I only know its indignant military regimes and the language that humiliates, where borders are drawn by the tumbling of their boots and the noses of their rifles. This is what language is to me, as a freelance translator. These are its borders; despite our experiences of life, they imprison knowledge at times and free it at others, in accordance with the tides of capital that asks those who are already at the top to decide on the “quality” of a linguistic text, and the “competence” of its invisible producers (the translators, the students, and other exploited workers of the field). Maybe here lies the importance of what was asked of me. Maybe my being asked about the profound meanings I see of my occupation from my often-invisible position is by itself an insurgency, even if partial, against the movement of capital and those who preside over it. Thus, I start as anyone who writes for the first time starts: with a quote.

… I found myself understanding the different ways in which I have been erasing myself and my narrative throughout previous drafts of this work, my desire to hide queerness in academic jargon … Even as I write this now, the desire to erase my own account from the research bears on. (Almazidi, 2020, p. 356)1

Indeed, very similar are the questions that we translators come to ask under the weight of an original text and an editorial policy in which we are merely considered pawns. A constant state of realizing the need for symmetry at times contradicts a yearning for re-interpretation. Writing is often complicit in reinstating the ambiguity behind the terminology and compositions of rugged academic methodologies. Accordingly, I ask: is the act of translation condemned to be that of a faithful servant who works with pure “integrity,” away from doubt or rejection, with the sole purpose of reiterating the author’s own vaguenesses? Does the translator's belonging to different spaces, her pondering over her own apprehensions, and her contextual social perceptions towards what we are reading as seekers of a Leftist salvation, have any say in this process of linguistic transfer? Or will the translators' thoughts remain an illegitimate secret up until they individually move from the ranks of service providers to the rank of independent critical writers, even if in all cases they remain in the position of selling their labor power?

I had to go into translation in general for several reasons, the first of which is political. Being married to a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon, I was prohibited from working. My education was in the field of education and language teaching specifically, so it was a marriage of convenience of sorts to practice translation as it was offered to me. Of course, I translated several subjects for different platforms; some of them intrigued me and made me happy, and others irritated me to the core. But every time I saw a challenge, I would confront the text or film or interview in a perilous, painful journey that felt like going into labor and eventually giving birth. In other words, whenever I finished a particular translation, I used to feel that I had put on paper or on screen a part of myself. But as soon as I felt happy with the fruit of my work, I was reminded of the need to sell it, silently and anonymously, to buy my family’s bread. It is the way of capitalism, be it in a factory or between agriculture fields or on a sofa at home behind a computer screen on the outskirts of a refugee camp. Although the beginnings were tenuous, I used to get upset from any criticism and I needed some time to train myself to accept it and improve my ability to translate in the way that my male and female employers required. I realized that the process of translation and its different subjects aren’t a simple mechanical conversion from one language to the other. Rather, it is a process where the translator coalesces with a certain linguistic and cultural system that she/he works on transforming to another similar, yet contrasting system. In other words, the translator’s mental and physical being and social reality guide that process. I used to feel committed when I translated topics that interested me and addressed issues that I valued more than others. And what interested me was my unique experience in translating for an academic magazine with a clear ideological path. I thought at first that it represented a part of my struggle as a woman belonging to a refugee society. However, the more I dived into translating different articles, the more I grasped the contradictory approaches that existed under the umbrella of the same ideological school of “Leftist Feminism,” as it was claimed by authors. The language of some of the articles was complex with no clear justification to that form. Its complexity pushed its ideas – that I happen to embrace closely – into ambiguity, and even altered it, hence diminishing its potential power had it been written in a simpler language. All those emotions and conclusions rose on the account of me being a proletarian-translator coming from the field of practice as opposed to having graduated from the institutions of theory. And if all of this signifies anything, it is that revolutionary ideology still languishes under the weight of elitist pens wandering the labyrinthic depths of language, in the mazes of which it fails to deliver ideas to and from the ranks of humbled classes.

Through the humble volume of my translation with Kohl journal, I found in the fluidity and the simplicity of some of the articles, amazing ideas that touch on and express clearly women’s and immigrants’ struggles from different parts of the world. These struggles are not confined to the global South: they extend to all the geographies and have reached a pivotal turn (post-1990s), shifting from one form of capitalism to another. Beautiful examples of the aforementioned are: “The Other Her: On daughters of abusive mothers and the silence about inter-generational trauma in Indian families,”2 and “Who is the migrant in ‘Migrant’s suicide?’”3 However, in other articles, I found difficulty in following the chronological and logical sequence that shape and are shaped by certain linguistic and conceptual structures, and where the writer her/himself shies away from the strength that resides in the simplicity of the subject matter. As such, it is a dilemma for me to shift between sticking to the linguistically complex style of writing on the one hand, and dissecting the ideas behind it to express them in a simpler manner that is also closer to the Arabic reader on the other. In theory, I have found the second approach of deconstruction to be more ideal, but in practice, it is more complicated. The delivery time assigned to the translator can and does obstruct this process most of the time, without mentioning the translation problems that come with the “scientific method” that the academic writer might use and that might be unknown to the inexperienced proletarian translator.

I believe that translation must be an independent extension to the source text, not a mere mirror of it. As people who live in a constant state of destabilization – the working class, selling the product of our craft for our daily bread – our chances to express our position regarding all that knowledge storm that takes our lives and their shadows as subjects, are scarce. This reality makes translation our only window of opportunity to transgress the transfer of knowledge and take a stance on it. For that to be achieved, attention must be given to the process of choosing the original text intended for translation: selecting ideas and content that reflect the forgotten class’ concerns and touches upon the feelings and sufferings entailed with the causes that our readers deem to be committed to, in a language that depicts the reality of these causes and transcends them simultaneously. However, this mission isn't assigned to us as translators; we are only asked to mimic without being allowed to interact with the text or submerge our critical self into its depths. Instead of our “baby” setting out to interact with the readers’ and subjects’ surroundings and develop to become a more evolved and mature idea, it becomes just another commodity for the pleasure of intellectual elites.4 It is those intellectuals that had every opportunity to get closer to our intellectual heritage, but chose to transform knowledge production into a capital driven occupation.

My thoughts circulate within the darkness that engulfs our daily lives, as a woman and a worker stuck in a battle with the never-ending spiral of social and knowledge (re)production patterns preordained by the different forms and cultural and political identities of the bourgeoisie. I don't what to add or elaborate on, because under the pressure of these (re)productions and the lethal logic of the capitalist era, my will to speak takes the shape of abstracted "emotional” forms, estranged from what is legalized and approved of by those who monopolize the "systematic" forms of knowledge production. If I am lucky to talk about some of my reflections here and today, it remains an exception and a product to the supply-demand chains of the market of knowledge production. Here, Karen Ravn might succeed – from where she stands between the halls and libraries of a faraway Swedish University – in describing what I mean and give my lived problem enough value to prove its worth in her article "The Permanent Crisis of Social Reproduction in Lebanon: From Past to Present,"5 that I was able to translate through a lucky collaboration with two communist radicals who happen to also be university students – or at least who lived in close proximity with the knowledgeable university bourgeoise. But still I ask, on which listening ears will my thoughts and translations fall? And what working body will it save among the ranks of the working classes? The answer is simple; I don't know.

This is exactly what I feel when I work on a translation: arduous labor thrown into the unknown. From my position, translation is related to the need to provide a decent living in a rapidly decaying country. The labor of translation is made into no more than an income-generating job, denied of the essence of its proletarian class. I find myself in a state of always questioning the commitment that supposedly accompanies such intellectual or artistic activity, during this apocalyptic stage of capitalism that casts the shadows of its permanent crisis on peoples’ lives.

I go back to the idea I started this article with: the acknowledgement that we are attempting to run away from many things, and by that we remain prisoners of the constructs that accompany language. It is not that we are incapable or limited or thoughtless, but language develops in two directions: one is dictated by stature, and the other by pragmatism. Both directions constitute a grammatical and political order in which we are domesticated to only contemplate our livelihoods. In the dark alleyways of knowledge production monopolies, we, the workers of the translation field, reside, by virtue of our craft not our credentials.

Money besieges us (the inhabitants of capitalist societies) wherever we go and however we try. It determines the extent of our conquests and our potentials, who we are, why, and how much respect we should be received with. I write things that come to mind and then erase them because I fear the rules, principles, and conditions dictated by the dominant production system. This monologue prompts the following question: how many people die carrying in their hearts a knowledge they did not reveal for fear of many things? Perhaps the correct question is not “how many,” but “who” is left without a celebrated narrative of their lives and a documented legacy of the labor power that was extracted from their bodies. The answer is simple: they are the proletarian class.

- 1. Almazidi, Nour (2020). "Queer Spatial Recognition in Kuwait." Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 351-368. https://kohljournal.press/queer-spatial-recognition-kuwait

- 2. Siobhan, Scherezade (2020). "The Other Her: On daughters of abusive mothers and the silence about inter-generational trauma in Indian families." Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 213-219. https://kohljournal.press/other-her-daughters-abusive-mothers

- 3. Yue, Emily (2021). "Who is the migrant in ‘Migrant Suicide?’" Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 68-73. https://kohljournal.press/migrant-suicide

- 4. In the shadow of an editorial discussion with the translator and the author, the three of us agreed that the plural form is intended here as it denotes the fact that the present intellectual elite does not relate to a single homogeneous economic class. It is stranded among the different complex strata of the neo-middle classes and particularly upper middle classes. Those strata may be deemed to belong to the working ranks of the neoliberal construct but often occupy the institutions of knowledge production including universities, journals, issue-centered NGOs, newspapers, solidarity forums, etc… with a systematic capital structure to fortress their being. They exist in varying forms of employment. We do not claim to provide a comprehensive deconstruction of the reality of that elite question but saw it to be necessary to mention it as a prelude to a longer discussion of the matter. (Translation manager)

- 5. Ravn, Karen (2021). “The Permanent Crisis of Social Reproduction in Lebanon: From Past to Present." Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, vol. 7, no. 2. Available at: https://kohljournal.press/permanent-crisis-social-reproduction-lebanon-p...