Cairene Ruptures

theoa2_copy.jpg

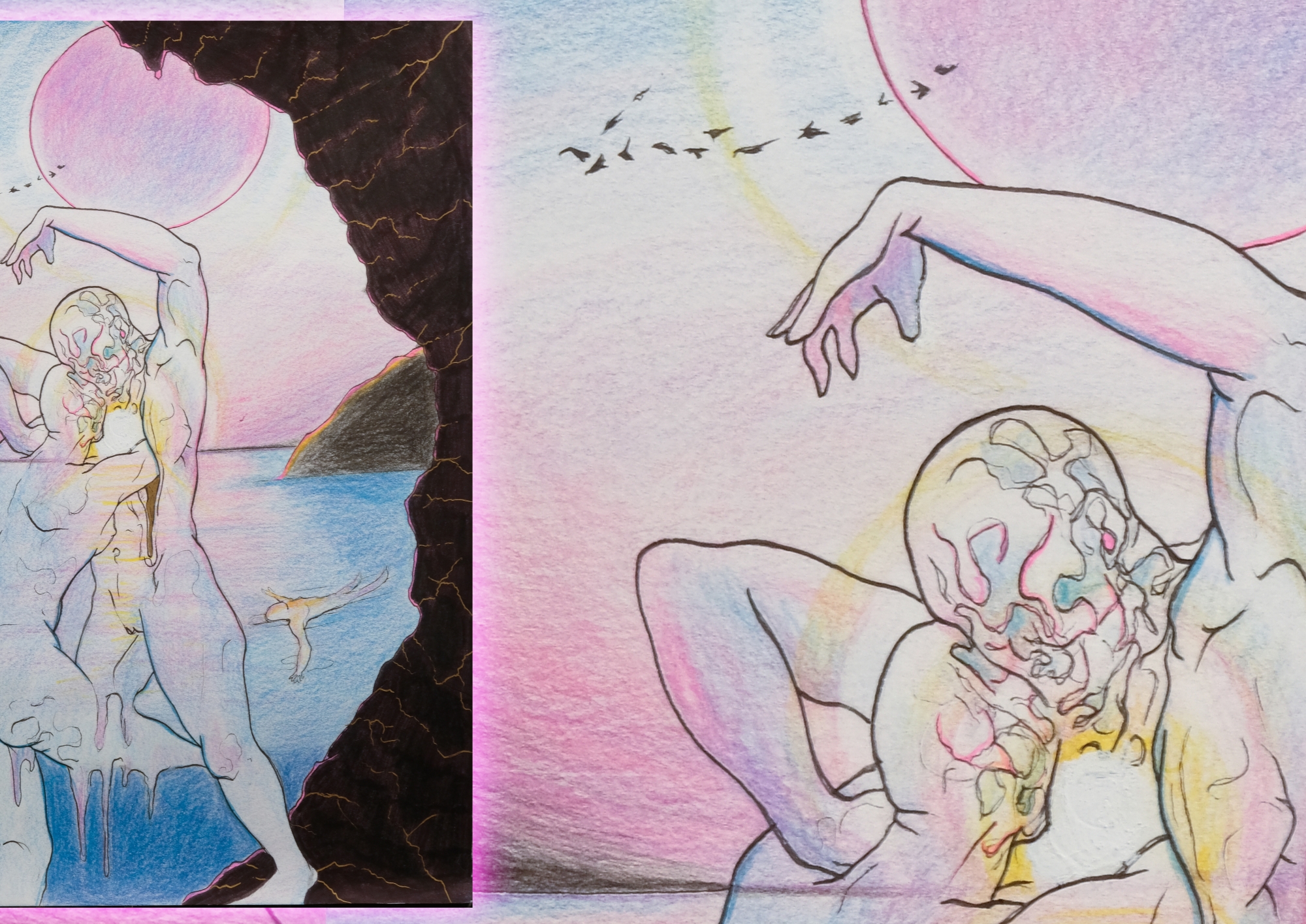

Battle in the cave

You like a woman. If you can share with her a text that you love about a queer narrative/history of an Arab city, then you’ve already taken the risk of possibly falling for her; no walls of protection and pretentious dating culture coolness that’s fundamentally uncool. If she likes it in a way that’s too Arab, too queer, then you’re living the impossible, the utter dream. A woman who loves women, and who feels like home but is not destroyed by it.

Words for me have always been super sexy. I’d reread my favorite sentences over and over growing up, letting my fingertips highlight them as if the words on paper would become more vivid. I do the same with women; I hold on to them, to the aliveness, wetness, and fire of being intimate with a woman. I grew up in a world where I didn’t know how sexual my fingers could possibly be.

I know when I am about to meet a book that will be a favorite. I also know when I meet a woman that we will both mark each other’s histories.

Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich – their histories marked mine; their words opened portals in me to verbalize my love for women, and only women. They erased the shame and confusion, and nurtured my life with endless possibilities of love, caring, hotness, longing, and belonging.

Last year, I was, as always, trying to survive Cairo’s toughness. I found a friend who is happy like I am, and who wants to maintain the innocence of how we found happiness in a super fucked up context. We verbalized love in the same way, for different genders. We went to swimming classes together; it was so helpful for our anxiety about life in Cairo and Cairo itself. We walked the streets lightly, agreed that we unfortunately loved this city, and exchanged and shared magical moments that we sought and that found us.

We used to go to a swimming pool with trainers. It was a middle/lower middle class space where queerness is foreign and we ourselves looked foreign though we were middle class women. We looked entitled and free and that resulted in a false class profiling, as if you could only be entitled and free if you were part of the Egyptian elite. One of the trainers, with whom we always exchanged this glance of “yes! I know! I too love women!,” had this top energy and always giggled at my clumsy swimming and مسباتي (my insults), shying away in an adorable way whenever I said أحة أو فشخ أو نيك. I was very aware of my privilege in this space: I am a lesbian woman who lives on her own in Cairo, validated by queers in my city, surrounded by queer feminist women whom I work with everywhere and with whom I share the everyday work of building a body of knowledge that is similar to my life. I still ache from the loneliness sometimes, the limitations of being queer in Cairo and hiding my queerness from my family, but I didn’t know about her loneliness or if she actually knew that it is okay to love women and own that love.

Can Cairo be magical? Can Cairo be queer?

I moved to Cairo 8 years ago; I now call it my city. I am so in love with it, yet nothing breaks my heart as much as it does. It is an absolute reality that cities mirror freedom as they mirror oppression. Cairo mirrors poverty, failed dreams, tiredness, helplessness, and sleeplessness. It doesn’t seem like we give up on its possibilities.

In 2013, I went to my first queer party and it was in Cairo. I was slowly coming out; I didn’t want to but I had to attract the attention of the women I liked. I was still sleeping with men so I was calling myself bisexual. I don’t think I was ever bisexual. I do have a fluid range of sexual attractions, kinks, fetishes that can be genderless, but I love women too much and I melt in a way that I can never with cis men. It takes a woman for me to melt, and it definitely takes a woman that experienced Cairo, this subtle understanding of what we fundamentally know about being raised in such a geography: the sense of humor, the oppression, the resistance, the power of dreaming, the things we hated when we were young.

Egypt can’t be queer, can’t be magical, can’t be happy. They try to convince us with their words, hatred, and mediocrity.

I met a witch on my vacation in Sinai. I told her about the first woman I loved, and that I was a writer. Both writing and loving women are essential in my life; both make me equally vulnerable. I was high, and she was a stranger, and I wanted to tell a stranger about what moves me the most. I call her a witch because as we were talking about literature, and feminism, and women, she mentioned Women Who Run with the Wolves, and I told her that she actually was the woman who ran with the wolves, and she told me to keep defining myself as a writer. We disappeared from each other, but under a sky full of stars in a place where you can be anything and still at home, affirmed each other. Her eyes and voice were soothing.

A high school kid in a governmental school in Maadi once stopped me to tell me that I look pretty and that she likes my hair. I was sure that it was my queerness. I thanked her and wanted to wish her a happy queer life. I hadn’t realized I had become a grown woman until that incident in my late twenties, being appreciated by beautiful queer teens in Cairo. My heart once melted when a girl passed me a note that said, “I just wanted to tell you that I love your hair.” I smiled and thanked her. I was in my favorite cafe working and having a meh day, but the youngness, the innocence, the random queerness of her gesture reminded me that this happens every minute in a place that shames its queer folks. Because of this, our lives are possible.

Cairo is magical. Cairo is queer. Cairo is beautiful.

I organized with the first woman I loved. No feminist organizing before our efforts together made sense to me. Before she made an appearance in my life and we exchanged books, I sat with women who were disturbingly heteronormative, so unaware of intersectionality, so elite or wannabe elite. They were disturbing, but they were the only women who were not like the women in my family, who combined choice with women, and who despised patriarchy. I later learned that patriarchy affects us so differently that they themselves can be oppressive. At a party, I met the only woman I appreciated; she had a woman partner. I almost othered my mother at this time. I was 18 and angry. I almost turned her into an enemy because she wasn’t them. I think I broke her heart by wanting/seeking lives and women that weren’t her. I was so blinded by the quest for freedom and validation that I didn’t see that she too needed validation/affirmation from her daughter. Ten years later, I know she’s the reason I am the beautiful person I am today. I tell my mother about the women I like/love. I don’t mention that they are my lovers, but I tell her how amazing they are. I talk to her about my queer friends/partners, and the non-queer ones with radical choices. I tell her about the woman that broke my heart. I was lost, broken, and needed my mother’s wisdom to guide me through the heartbreak. I asked my mother if love was supposed to hurt that much. I wanted to be like my mother, capable of falling in love again and again, so I asked her how she moved on from her first love. She was beautiful when she shared her reflections with me, a joyful wisdom. Nothing about my mother is broken.