Palimpsestic Histories: Real and Imagined Conversations about Queerness, Mothers, and Memory in Egypt

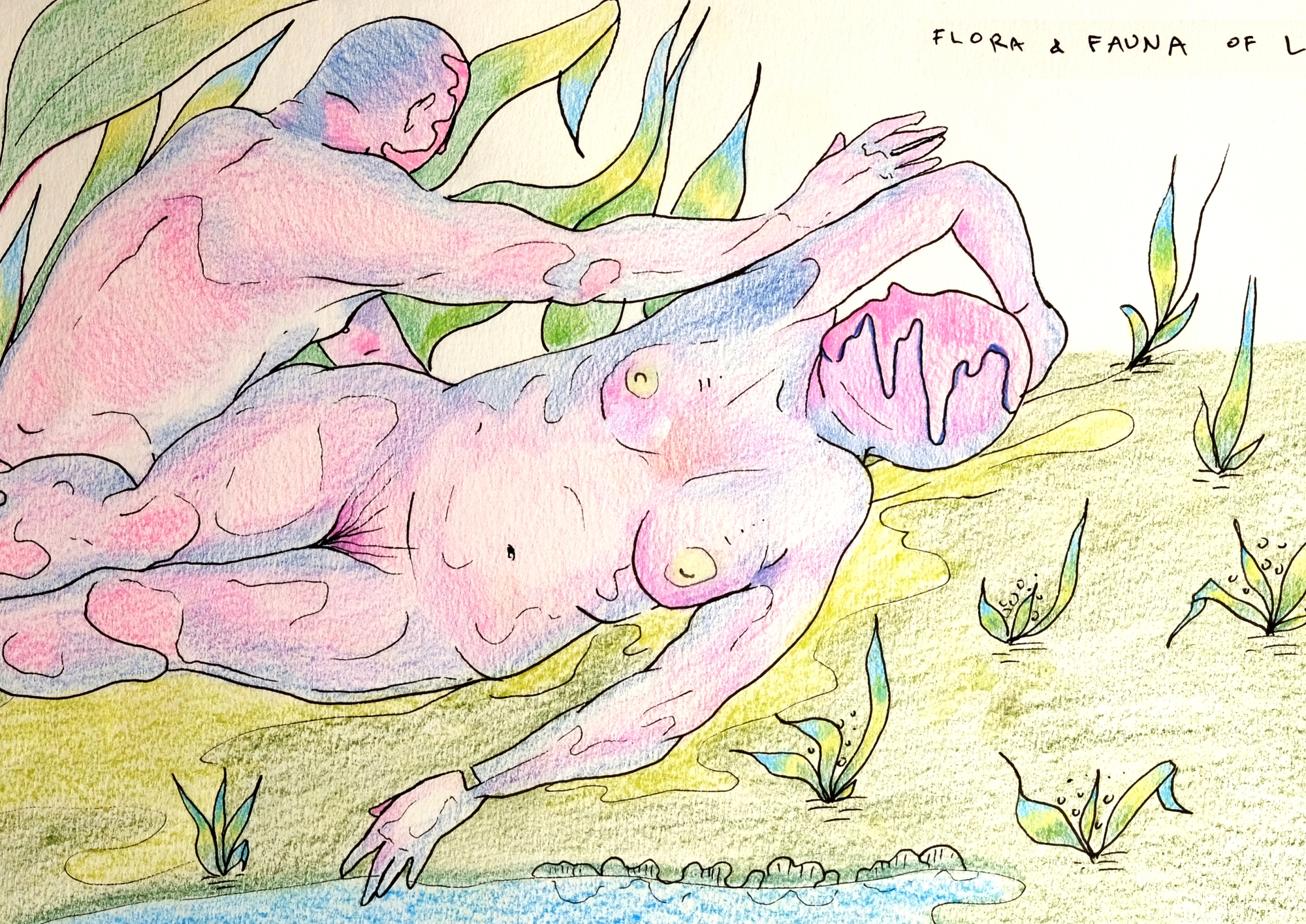

theob1.jpg

my friend M. with the love she deserves resting by the pond

Dedicated to Sarah Hegazy.

We may have never met, but your memory, your presence, are so palpable to me and countless others, that it feels as if we have. I hope you have found home again.

I have walked down this street, my street, more times than I care to count. Rows of trees on either side cast tall shadows on the long stretch of asphalt. It is my street, but it does not have a name. Or its name here is irrelevant because I cannot reveal the specifics of where I live. Not of the street, or the neighborhood, or the city. This irks me. Names are important to me. They ground me, anchor me to a spatio-temporal setting that feels larger than the little bubble I occupy. But protecting said bubble is more of a priority right now.

With the exception of major events such as Queen Boat or the Mashrou’ Leila concert in 2017 (also known as the Rainbow Flag Incident), both of which took place in Cairo, queer history in Egypt seems mostly to have been written in the shadows: in quiet café corners, private house parties, crowded dance floors – stories behind closed doors. Under a ruthless military dictatorship that openly disdains queerness, this is hardly surprising. With necessity, with a constant need for security in order to survive, the details that make us who we are, the names that roll off the tongues of the ones we love with easy familiarity and intimacy, have to be sacrificed. Reality, in whatever shape or form, and imagination merge to create an ill-y demarcated history, one born out of a blend of fear and hope.

Black American novelist Toni Morrison coined the term “rememory” to refer to a narrative tool that relied on memory as a substitute for recorded history – as recorded history could not be trusted to give her insight into the culture specificity she wanted. Rememory entailed “recollecting and remembering as in reassembling the members of the body, the family, the population of the past” (2019).

As I step into the cool lobby of my building, I take a moment to pause and breathe. I engage with Morrison’s concept of rememory and reconstruct a scene that took place in this very lobby: the weather is slightly warmer and stickier than today. I push open the heavy double iron doors of the building, pulling my partner, Nadine*, in behind me. As the door clangs shut behind us, I give my surroundings a customary scan before I kiss her. She kisses me back, lips lingering on mine. I smile, cloaked in the secure dimness of the lobby. But this memory is only half true. As is the rest of this piece.

Upstairs, Nadine opens the door for me. I grab my cat who was trying to stealthily bolt outside. I recount the thoughts I had in the lobby – new, old, and imagined – as Nadine boils water for tea.

“It just frustrates me,” I continue, bending down to scratch behind my cat’s ears. “The lack of specificity, the dearth of names in Arabic queer works. I know safety comes first, but I wish we didn’t have to resort to imagination to fill in the gaps, you know?”

“But why do you talk about imagination like it’s of secondary importance?” Nadine asks, “I remember reading this book by Kathi Weeks…the name escapes me right now. No, wait! The Problem with Work. And she was talking about how ‘going beyond’ or imagination is a way to approach the link between historicity, presentism, and futurity.”

“I’m not saying it’s not important. Do you know when people say pictures or it didn’t happen? Sometimes, I feel like it’s documentation or it didn’t happen, you know?”

“I feel like you’re talking about history and archiving maybe in the traditional sense, something that is tangible…”

“Yes! Something I could show our kids, you know. If we ever have any!” I laugh.

“I get the appeal. Of there being like material evidence that we as queer people…we are talking about queerness here, right?”

“Well what got this whole conversation rolling was imagining us kissing downstairs. We can’t do that. It’s too risky. And that’s what got me thinking of queerness always being kind of invisible. It’s there, it exists, but you can’t see, touch, or smell it.”

“Smell it?”

“You know what I mean.”

“Yeah, I think about that sometimes. It’s like the shock I felt when I learned that this older professor died, and then I learned that she had a partner, a woman. It’s like queer older women don’t exist. It’s like queerness is something very young and small and immature. It makes you feel as if it’s just a phase you’re going to get over, even if you’re 30 or 40 or something,” Nadine laughs.

“That’s what I mean. I often feel like if I don’t post something on social media then it didn’t happen.”

“But I’m not even referring to documentation in the material sense. I mean more along the lines of documentation in the sense of existing. Not even in the loud and proud sense. You know I’m a quiet person.”

“A quiet gay.” We laugh.

“Yeah a quiet gay, like documentation in the sense of living openly. Existing openly. Not even in the traditional coming out sense. Just having the option of not censoring yourself or omitting information.”

“This is making me think of the infamous Mashrou’ Leila concert we attended back in 2017. Which makes me wonder, how important is the idea of a queer history to you? Like Queen Boat, Mashrou Leila’, the hammam raids. Like, do you feel a sense of ownership? Do you feel connected, disconnected from them?”

“I feel mostly disconnected. Funnily enough, even with the events I witnessed. Even when people I know tell me about events they witnessed.”

“Why?” I asked.

“I just don’t understand how to develop a sense of ownership over these events. There is this sense of disconnectedness with this timeline. I identify more with the feelings I felt. The history of my fear, for example. I can trace my own personal history as a queer person living in Egypt in a way that’s very different than the grand narratives. But maybe it’s a me thing. I feel like other people, like activists, people more in tune with what’s happening on the ground, might have a different relationship with the events that happened. When I hear about pre-Queen Boat times and before the hammam raid, it’s all interesting to know but I just don’t feel connected to it. It’s like when someone recounts what happened during the revolution, but in Cairo. I’m not from Cairo and I didn’t live in Cairo during the revolution.”

“When I read that paper by Sahar Amer about medieval lesbians and the story of the two Hends, I was like okay, this is a legacy, a sort of history that I can call my own. That’s what I mean by ownership. Something that is not ‘imported’ from the West. Something that is more Arab, or from this region. So when I talk about history and ownership, I mean something I can identify with more. This is in addition to each person’s personal history of course. I’m talking more about a collective history. The kind we pass on to younger generations,” I said.

“I just don’t really understand the concept of history in this context. I feel like it’s full of gaps, it’s fragmented and nonexistent. I mean, either you define queer history in Egypt as a series of events related to state crackdowns on the community, or you create a history by reading in between the lines and imposing queer readings on certain events. There’s so much that’s missing that I don’t have a relationship with it. It’s not palpable. It’s elusive. I mean, I could be gone tomorrow and there would probably be no record of my existence as a queer person,” Nadine said, pouring boiling water over the tea bags and handing me a mug.

“I don’t mean,” she continued, “that documentation is necessary, but I mean, because of all the security measures and our precautions in making sure we don’t leave traces behind, to prevent ourselves from being persecuted, there’s very little that’s known. But I know that’s changing. People are writing things that wouldn’t have been possible 10 years ago, not even 3 years ago. There’s a wave of documentation that’s happening. But I feel like I’m over it. I feel like I needed it at a certain point and it wasn’t there.”

“I get what you’re saying, but I still feel like I need it sometimes. A guide, an archive. Something to fall back on, in a sense. A way of situating my queerness in time and space. I don’t even picture, like, a traditional, state-authorized sort of archive. It’s like that paper you sent me about queer archives being messy.”

“I’m drawing a blank.”

“Hold on, let me pull it up.” I pull my laptop out of my bag. It slowly whirrs to life. I sift through my cluttered desktop before finally locating it. “It’s called ‘The ‘Stuff ‘of Archives: Mess, Migration, and Queer Lives’ by Martin F. Manalansan IV. I think I have the whole document highlighted,” I laugh.

“The title sort of rings a bell. What do you have highlighted?”

“Like, I said, almost the entire thing! But wait, let me read you this part that I think is relevant to what I was trying to say:

The ideal archive is about the management of the morass of memory. But what happens when disorder and chaos are the elements that make up the archival space? What happens when, instead of orderly catalogs, makeshift arrangements teetering on the brink of anarchy become the “disorder” of things? What kinds of value get attached to persons and things that dwell in mess and disorder, and how can they be dynamically reframed as a way to think more broadly about political acts, aspirations, and stances? (102-103)

So in the paper, he basically talks about ‘queering’ the idea of the archive. The paper is essentially about locating a queer immigrant archive, but I feel like a lot of what he says can be applied on a larger scale. Maybe it can even be applied in our context. Like listen to this part, too:

Such a messing-up mission reverberates in the kinds of queer scholarship that focus on the recognition and centering of underrecognized practices, stances, and situations that deviate from, resist, or run counter to the workings of normality. Far from romanticizing deviance and oppositionality, I intend to locate discomfort, dissonance, and disorder as necessary and grounded experiences in the queer everyday and not as heroic acts of exceptional people. (97-98)”

“Yeah, I like that. Our lives are quite messy, aren’t they?” says Nadine, laughing. “I’m still not sure how an archive like that could be conceptualized, but I like the idea of messing with ‘normality.’ The messier, the more fragmented, the better.”

The doorbell rings, and the cats – there are two – hurtle towards the door.

“Oh! I forgot we had people coming over,” I said, shooing the cats away from the door. It’s Sarah*. After a round of hugs, she joins us at the kitchen table. I get up to make her tea, and Nadine grabs a box of cookies from the counter. We catch up a little. Sarah catches sight of the open document on my computer.

“Ooo what are you reading?” she asks.

“Heh. I’ve already kind of finished it. I was just reading a part out loud to Nadine. We were talking about queer history, documentation, and queering archives.”

“Wow. Weighty stuff. That’s funny. Well not really funny, but I was just talking with my sister about the Orlando shooting the other day.”

“What was the context?” Nadine asks.

“I think it was something about my mom and her reaction to it. It was very triggering for me. I remember telling my mom about what happened, and she was like, yeah, they shot up a night club. I said, yeah I saw and a lot of people died. ‘Well, they were all gay,’ she said, ‘so it’s fine.’ That really upset me. She realized she’d upset me and told me she was just joking. And I was like that’s not really funny. And I get it. My mom kinda has that sense of humor, but it’s a topic that’s really sensitive to me,” Sarah sighs.

“I know what you mean. I think a lot of us were triggered that day. I remember telling my therapist that it felt like the two important aspects of my identity, my queerness and my religion, were battling it out in public. And I think I cried at some point, and mama asked me what was wrong, but I couldn’t tell her. I mean, she knows I’m queer, and she knows about Nadine, but she’s still in denial about it,” I say.

“Yeah, I’m not out to her either,” Sarah says, “She doesn’t want me to come out to her. She doesn’t really want to deal with that. She knows, but she doesn’t wanna know. My sister has always been like the mediator, and she’d ask my sister what my deal was. She’s be like, is Sarah going to get married at some point or what? And I’ve never really come out to my sister either, but she knows I’m queer. And she doesn’t really ask unless it comes up. And my sister was like ‘I don’t know; ask her.’ And it’s because she knows she never will.”

The doorbell rings again, and our last two guests, Marwa* and Tara*, enter. Another round of hugs and greetings. More water is added to the boiler. More mugs are brought out. We move to the living room, where there’s more space. It is now an hour or so before Maghrib. Golden light filters through the white crochet curtains, projecting diamond patterns onto our skin.

We tell them what we were talking about and Tara groans. She hasn’t spoken to her mother in months.

“I wish I could come out to my mother, as pansexual and trans,” she pauses as she undoes her long hair from its ponytail, “but I don’t think I can until I’m fully able to pass as a woman. Then she’ll have to deal with it.”

“I just wish…I don’t know,” I pause a second to collect my thoughts, swilling the remains of my tea in its mug. “You all know my baby sister got married recently. I love my sister. She’s one of my best friends. But I couldn’t help but feel a little jealous, you know? Like my mother was helping her with everything. Everyone bought them stuff for their place, and I know it’s maybe selfish to think so, but I just wish I – we,” I say, turning toward Nadine, “I wish we could have had that too. But we’ve had to do things on our own. It’s just sad and frustrating that I can’t turn to my own mother for help when I need it,” I say.

“Yeah, my parents have pretty much banned me from having relationships, so I can’t turn to them either. I only did the first time, when I was in a relationship with a guy, and that was a disaster,” says Marwa.

“That’s the case with me too,” echoes Sarah, “Like all the time. I always felt this barrier between me and my parents. Like I couldn’t always ask for things or ask for help because if I did, I was going to do it wrong. When I was really young, I’d ask really provocative questions as a child, and both my parents were like, we’re not going to talk about this. Nip this in the bud, here’s the lie, and now let’s clean everything up and don’t talk about it. So, I became a very shy person, and I didn’t really turn to my mom a lot during that time because of the fear of provoking some sort of reaction I wouldn’t be able to deal with very well. So I turned to my sister more.”

“I can be a bit more open with my sister, too,” says Tara, “but it’s really hard having to face society without true familial support. Especially when you’re trans and pan. Things would have been really different if I wasn’t. Especially with hormone therapy. Like when my breasts started growing a bit more, like when I finished my laser hair removal sessions. And there are health-based fears with hormone therapy. And it can really wear you out, physically and emotionally. And that makes it hard, not having your family there for you. It makes me feel like I’m facing society alone. Especially when you’re trying to pass and trying not to get hurt by society in the process. It’s especially scary when you’re doing it alone. Even with communication. I’ve stopped communicating often with them because it feels fake, like a lie.”

“I think I’ve normalized not being open about my queerness, about my relationship with my mother,” says Nadine. “It’s become second nature to omit information and things. Talking about the small details, not the big ones. Maybe because I didn’t have a close relationship with my mother, so I didn’t feel like I was really hiding anything, because we didn’t really share anything. But I feel like that’s changing a bit, especially as I get older. When you hit 30 or 40, it’s different. Yeah at a certain age, it’s cool to be discovering yourself and living alone or with your friends, but the older you get, it becomes more palpable that you’re not saying things. And people seeing you a certain way also exacerbates that. Like I remember when my sister-in-law was like, yeah you’re probably traumatized by your parents’ relationship and that’s why you don’t want to get married. My parents are divorced. And yeah it’s true that I have issues with marriage as an institution, not necessarily with commitment. So there was this assumption, when I brought along Hend as my ‘friend’ for like a family dinner, there was like an attitude of why did you bring your friend? I feel that it just gets more and more tiring to lie, omit information, or twist the truth. Small trivial things like someone asking you what’s wrong and you not being able to reply that, for instance, you’ve had a fight with your partner. And even then, at the end of the day, it’s like I said, my relationship with my mother isn’t even that intimate, and I don’t tell her everything.”

“You know what’s funny? Well not funny, funny,” I smile, looking at Sarah, “But yesterday, I was reading Audre Lorde’s Zami, and being who I am, I skipped a bunch of chapters and went straight to the epilogue, and there was this line that just stuck with me and made me wonder about stuff. Hold on. Let me grab the book.” I come back with the book and flip to the ending. “Yeah, here it is, she says: ‘There – [she’s referring to her mother’s homeland] – it is said that the desire to lie with other women is a drive from the mother’s blood” (256). That just got me thinking. Most of our mothers either don’t know or are in denial about our queerness, but what if we got it from them?”

“Our queerness?” Nadine asks.

“Yeah, I mean from them or someone in the family. And I’m not talking about the whole nature versus nurture debate here, but I mean am I the only person who feels like this? Looking for clues within your family history, trying to situate yourself? I think what I’m asking here is, where do you think we get our queerness from?”

“Hmmm, that’s interesting,” begins Marwa, “I think it’s complicated because sometimes I feel like both my mom and dad could have been on the spectrum of queerness if they’d had the opportunity to explore that.”

“You know, one time I’d been telling a friend of mine this story about my mama, and she was like, maybe your mom is queer,” Nadine says.

“That’s really interesting, because sometimes I feel like my queerness comes from a very strong maternal line that started, as far as I know, from my maternal grandmother. I heard that she had a strong personality. Not to say that that meant anything. I mean. I could tell that she rejected gender norms. Her role and relationship with my grandfather didn’t feel heteronormative. I’m not saying that that meant she was gay or would have been gay, but this is something I’ve thought about a lot. If there was someone I could have inherited this from it would have been her. My aunt and mother too to some degree. And my [female] cousin,” muses Marwa.

“I feel that, aside from traditionally Western categorizations of sexuality, queerness has always existed in many different forms over the years. Mama at one point told me that my queerness, which at the time I thought was linked to my OCD, was normal. There was also like an ambiguity, a blurriness almost, in my grandmother’s relationship with her close female friends. An ambiguity that maybe if it were scrutinized today would be labelled as queer,” I say.

“I could also see some queerness in my dad, too, that I feel I’ve inherited,” says Marwa, “When people say I’m weird or aloof in some way, this thing I get from my dad. There was a phase where I dressed very queer in a way, and one time when I was going through a photo album with my dad, I saw that his style was also very queer. He and his best friend would dress alike, his best friend who’s gay –”

“You think he’s gay?” asks Tara.

“No, he is gay. He’s not out though, but I know through, erm, sources. They would wear weird clothes: super tight white pants and bellbottoms, and they had these mustaches, and wild patterned t-shirts, awesome t-shirts. I wish my dad dressed this way now. This is something I would like to interpret as queerness.”

“That’s really interesting about your dad, because it reminds me a bit of how I relate sexuality to my dad, my stepdad, that is. He has always been a bit of an odd duck. So I grew up with a stepdad who was pretty much celibate in my eyes. He always came across as a very large child. A very fun-loving, silly counterpoint to my mom’s stern, making-sure-the-house-doesn’t-fall-apart person. So my dad was kinda just this big teddy bear. Kinda completely desexualized in my eyes. So yeah, I don’t know if that relates to my asexuality but it kind of gave me permission to not need sex or feel like a lack of a want for that made me an odd person,” says Sarah.

“That’s really interesting. The idea of inheriting something from a non-biological parent,” I say.

“Yeah, it just kinda normalized the lack of sex in a person who otherwise should’ve been sexual? An American man who lived in Egypt and talked about things very openly, but he was very much like a sexless being in my life. He’ll make jokes about sex, but yeah,” says Sarah.

“I don’t know, though,” says Nadine, “When that friend told me that maybe my mama was queer, I felt sort of an aversion toward the idea. I felt like it denoted a sort of desperation. A desire to create a history where there is none. Maybe it’s pride. Maybe I feel like I don’t need a history or stories to make me feel validated. Maybe because I used to do that before. The searching for queerness in the unspoken, the erased. The scrambling to find queerness in anything. I don’t want to need this. I don’t want to be validated by making up stories.”

“But queer stories have historically been erased and continue to be erased, hence why some people feel the need to go looking for queer subtext in stories,” I point out.

“Of course,” Nadine concedes, “that goes without saying, but I think with me, maybe it’s coming from a place of anger. A need for independence. Perhaps it’s also coming from a place of bitterness. I mean, even stories about celebrities, like Umm Kulthoum, and the rumors of her being queer, I just feel, like, meh toward. I feel like I don’t need these stories as validation. And maybe it’s also fear of romanticization. I’m afraid someone in 10 years or so will come along and romanticize my story, for example, for their own personal agenda.”

“I get the fear, definitely,” I say. We all sit silently for a moment, reflecting quietly as we munch on the cookies, which have now gotten a little stale.

“It’s interesting the idea of inheriting things, traits, from our mothers or parents. Like with my mother, she doesn’t know about me, but she’s really kind, and I feel like I’ve inherited that from her. Mama is kind and so I am. Like, I don’t mean to praise myself, but I mean that I don’t hurt people. Not like my father did. I mean, because of the trauma he’s caused me, I have trouble trusting anyone. I only depend on myself. It took me a bit of time to create close circles. Like he was very, very, very, very strict. He caused me so much trauma. He used to remove the locks from our bathroom doors and wedge napkins in the doorframe so I wouldn’t stay inside too long, and I had a strict curfew, and he always wanted me to present as masculine,” says Tara.

“That makes me think…I mean, you’ve been through so much, but you’re working hard to make sure you don’t turn out like your father. And that makes me think about how we deal with our various traumas, and how we inherit our parents’ various unresolved traumas, but also how many of us are trying to break the cycle, you know? Unlearning harmful behaviors and healing from our trauma,” I say.

“Yeah, that makes me think of my relationship with my mom. My mom is a compulsive liar, and I realize she does it because she likes being nice to people and doesn’t want to hurt their feelings. And I realize that I do the same sometimes, and I’m trying to stop doing that. Trying to break the habit. I’m trying to break that habit in myself and in my mom. I’m also trying to make peace with the fact that ‘breaking the cycle’ is a lifelong process,” laughs Sarah.

“True, and we also talked about how parents sometimes do this thing, I think you called it ‘misremembering,’ Sarah, right?” I ask, turning toward her.

“Yeah,” she laughs.

“What does that mean,” asks Tara.

“Well,” begins Sarah, “it’s basically how, my mother, for instance, will reconstruct or reassemble events and memories, so that she remembers them in a way that cleanses them of any trauma or pain. Like with childbirth, for instance. I mean, when she was giving birth to me, I came out shoulder first, and my mom literally punched the doctor in the face because of how painful it was! So it wasn’t all wonderful and rosy like she made it out to be for so long.” We all laugh.

“You know my mom’s a gynecologist, and it’s funny, because I always felt that she felt that birth was a magical thing for her to witness. I mean she never told me that outright, but yeah,” says Marwa.

“I’m sure it’s different for everyone,” I say, “Maybe it truly is magical for her. But yeah, the idea of ‘misremembering’ is so interesting to me, because I often wonder about how powerful it can be. Like, I always tell this story, but –”

“The one about the guy who was caught having sex with his boyfriend?” says Nadine with a smile.

“Haha yes! I always tell it, because it’s crazy how powerful denial can be. So, this one time a friend of a friend of mine is at home with his boyfriend, and his parents are away on a trip, okay? His mother returns because she’s forgotten something back home. So, she accidently walks in on him having sex. The boyfriend bolts out of the apartment. The mother then falls silent. After a stretch of uninterrupted silence, she turns to her son and says, don’t bring girls to the apartment again, okay?”

“Oh wow,” says Marwa.

“It’s just, how do you do that?” I ask, “How do you perceive something in such a way that you simply erase what you don’t like from the memory? It’s incredible. Mothers especially, like I know this is a major generalization, but Egyptian mothers take the prize for being masters of denial.” Everyone laughs.

“I think that’s a very valid generalization to make,” laughs Sarah.

Marwa gets up to take a call, and as if on cue, Tara, followed by Sarah, rise to their feet. Both have work early tomorrow morning. After a round of goodbyes and promises to meet up again soon, Marwa comes outside and says she too needs to head home. Soon it was just me, Nadine, and the cats again. Nadine heads inside to prepare for bed, and I’m left alone with my thoughts. I shut my eyes and I’m back to where I was this afternoon, in the cool interior of the building lobby.

When I think of history, or the body as history, I’m reminded of palimpsests. Those recycled rough stone surfaces that were used over and over for writing purposes, back before the invention of paper. I picture our bodies as living, breathing, walking histories, inscribed over and over with events, words, and relationships, real and imagined. It is from this liminal space between real and imagined, that I wrote this piece: an imagined conversation between five self- identifying queer Egyptian women, based on one-on-one conversations about pain, mothers, queerness, and transgenerational trauma.

Logistically, arranging the above conversation in real life would have been difficult. For one, they do not all know one another. Secondly, given the heavy subject matter and the general reticence many queer individuals in Egypt demonstrate, myself included, when it comes to disclosing their personal history with queerness, I decided that it would be best to collect their stories individually, then combine them, with their full knowledge and consent, to construct an imaginary conversation between the five of us. Though I had initially started out with the intention of making some sense out of the messiness of those topics, I’ve learned in the process of writing this paper that messiness should not necessarily be avoided. To queer is a conscious act, and this is my small attempt at queering an Egyptian archive.

* All names have been changed to protect the identities of the people interviewed for this piece.

Amer, Sahar. (2009). Medieval Arab lesbians and lesbian-like women. Journal of the History of Sexuality, 18(2), 215-236.

Lorde, Audre. (1983, c1982) Zami, a new spelling of my name. Trumansburg, N.Y.: Crossing Press.

Manalansan, Martin F. (2014). The “Stuff” of Archives: Mess, Migration, and Queer Lives. Radical History Review, 2014(120), 94-107.

Morrison, Toni. (2019). 'I wanted to carve out a world both culture specific and race free': an essay by Toni Morrison. The Guardian, 8 Aug 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/aug/08/toni-morrison-rememory-essay

Weeks, Kathi. (2011). The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries. (1 ed.). Durham: Duke University Press.