Ripples of Magic: a Conversation Across Time

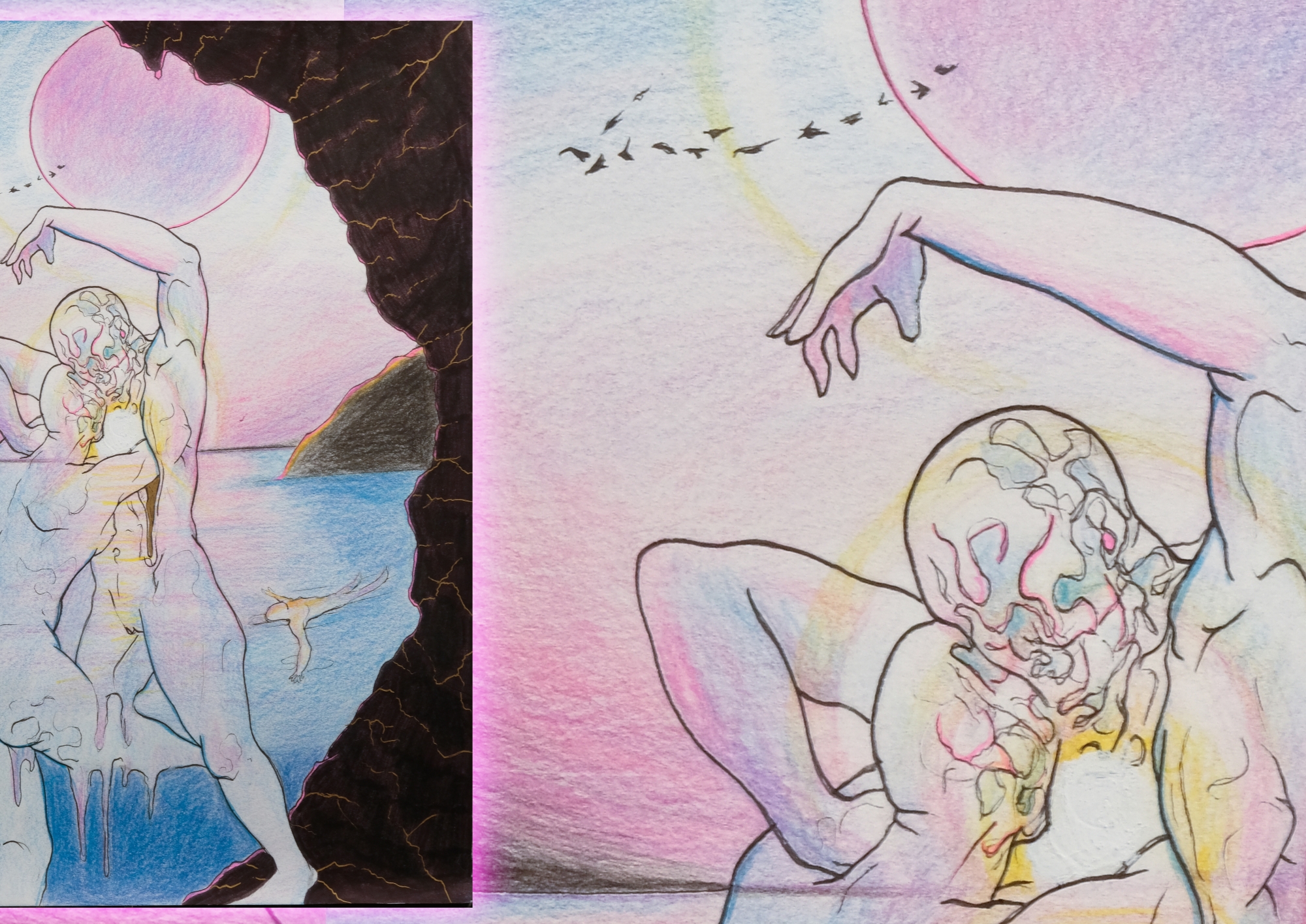

theoa2_copy.jpg

Battle in the cave

December 2, 2020, Paris

Ghiwa:

My loves, for I do not know how else to address you,

Exactly a year ago, we were creating magic together and seeing it unfold in our very hands. I am now sitting at my work desk in Paris, counting the traumas I have carried since, and harnessing our collective power from across our temporalities. The goosebumps that erupt on my skin upon reliving your words are ripples across time and space.

On the last circle we cast together, I gave you three questions to answer: What makes you want to archive this space? What has shifted for you? What do queer feminisms mean to you now? From a different time and space, I will attempt to answer these questions for you.

I want to archive this space because how could we survive, if not through the memories of our encounters. Trauma held what I thought were memories of joy hostage, so I made a list of them whenever one managed to slip between the cracks. Not once did memories of our workshop make it through. This is exactly how systems of oppression work against us: they strip us of our most transformative experiences. What we lived together was not joy; it was power, and we found collective joy through that power. And so, I want to archive us because I want to remember you/us as an act of resistance.

The praxis of memory as archive has not changed for me. What has is that somehow, despite it all, we managed to write ourselves back into our narratives. When I think of queer feminisms, I think of you, making it a reality in contexts that have been (and continue to be) economically, politically, historically, epistemologically pillaged and occupied and ruled by authoritarian regimes. You/we are the embodiment of queer feminisms. And I, too, want more. I want more of you, of us, together, in the world.

I carry you with me, like a palimpsest between the belly and the heart.

December 3, 2019, Beirut

Sarona:

What makes me particularly excited about this being recorded, remembered, archived, is because we are in a wider moment and we are a wider moment. We are in Beirut; it is the backdrop of the revolution. We can hear it, we can smell it, we went to it briefly. This workshop, I kind of wasn’t fully processing that it is happening because I never thought this could happen. Every day that I have been here, the space has made me realize how the impossible can happen. We are multiple individuals coming from completely different contexts, and as we spent over seven hours a day in the same room for five days getting to know each other, we are now entangled with each other’s lives. Despite the multiplicity of trajectories of us experiencing, realizing, embodying queerness, these entanglements illuminated the different ways that bring acts of defiance against the state, against the powers that are working against us, against us even being able to be here. I went to a very white zionist upper class high school, and I was the only Arab there from a very working class family. How can you exist within spaces that are not designed for you? In its banality but also in grand spectacles, these moments can be continual reminders of what those spaces can do to you mentally, physically, emotionally. The majority of my life, I only heard about people like us, through the mouths of others that are not us. And representations by others that are not produced for us, that only see the consumption of us, are why I think Kohl and us coming together is incredibly important. What has shifted for me? I think the question is what hasn’t been shifted, and what hasn’t been transformed, and what hasn’t been reassessed. This has been one of the most incredibly challenging and rewarding five days of my life; nothing was left unturned. It is because of the amount of effort and time that each person has put into this setting but also into each other, bringing forth concerns about how we can do better. That kind of vulnerability, taking that leap of faith, is ultimately what this is about. I have been keeping notes on embodiments, their intimacies, and the vulnerabilities and anxieties of perhaps not embodying what we think we should be embodying. The workshop call on Kohl’s website talked about moving away from hegemonic articulations and academic knowledge production. I thought those are really pretty, but how can I do that? Yet, we did, which is why I think it needs to be documented, not for legibility but for ourselves, so that people who come from where we come from know that these things too can happen. They have happened and they will continue to happen. So, I say, and I will be bold to do so, that we have produced queer feminisms in this space. It’s been through the kind of trust that we created, taking steps on how to do things for each other, but more importantly learning to show up for those who experience different strands of repressions, that I might not experience because of the way I look, because of the way I speak, because of the passports I hold. A few things that are sticking to my skin from the workshop – tangibility, this desire to have something from our experience to hold on to, to bear witness to, hope, death, imagination, things that we see as out of reach, not being enough of something. So bringing that back to moments I have encountered ideas of feminisms, they have often been presented as this room you enter after reading bell hooks. You go into that room, and you nod your head and lock the door and throw away the key and that’s it. Feminism is here. But this space has really embodied what queering feminisms and spaces can and should take on, which is continually interrogating and pushing, nurturing and growing in our entanglements and in mess and slipperiness. What I want to leave this space with is an open invitation to you all, because I want us to continue this journey together. We will figure out what this moving looks like for us, what it is towards, what this towards becomes and what forms it takes on, when we are in so many places at once. But in our “at onces,” we are in so many different times – whether in the inherited now or in our imagined futures. This leads me ultimately to a moment that resonates greatly for me, a point of thought that Jaha and Kawthar brought in, which is about how we harness this momentum, how we move on beyond this shimmering intimate small bubbles of revolutions that we have started here.

Ahmed:

It has been really difficult for me to situate my own politics in feminist and queer spaces I am in, be them here or back in Cairo, and think about how they can be seen. A lot of times I find myself staring off into a different direction. With non-feminist spaces and cishet people, this is not even a consideration I have because the conversation is so far, and I feel more relaxed. But in most feminist spaces I feel hyper aware of my own transness, in a way that can be productive at times, and at others very limiting, just because it makes me feel that I have to make myself smaller. I have this awareness that I was assigned male at birth, and that as soon as someone sees me they understand or read me as a man. So it makes me want to not, at any point, be perceived as too masculine or too “manly” or take up too much space or manspread or whatever. Even something as simple as doing a round of introductions and sharing pronouns can make me feel even more singled out. It brings up a lot of considerations like “am I being trans enough?” “Am I honoring the trans people that I know or the trans politics that I want to be part of?” I am at this point in my trajectory where I do not want to rehearse my stories of trauma to make myself legible, but I understand how these stories are important for other people to understand, and to take part in these conversations. But we are not starting at the same point. I feel that I cannot engage in conversations that much because there is so much that needs to be prefaced and said before I can start speaking about the kind of questions that I have. And honestly it is really refreshing and generative for me when I can have another conversation with a trans person about trans issues and think about transness in an intellectual and structural way. But they are not conversations that I get to have a lot of, even in queer feminist spaces like this one. I keep having this kind of hope for a space that has room for my politics – not only tolerating them, but engaging with them on that level. Even when trans voices are centered there is a lot of very implicit misogyny and homophobia that occurs in the form of polite tiptoeing around trans issues. I understand where it is coming from, I understand that people do not want to offend or make anyone feel excluded. I have appreciated everyone here trying their best to make me feel included, but I still felt difficulty trying to articulate these questions. I don’t have any concrete answers, but it is a process of me silently, individually, and sometimes in conversation with a few of you on a more intimate level, reconciling them with myself. It is unfortunate that I couldn’t feel present in this space earlier on, and I hope that it is something I can work on and that we can talk about more – not only including trans people but also how and why we are including trans people. That is my intervention, it has been stuck in my throat for a few days. I am just thinking about the space I have in Cairo with my queer friends, the majority of whom are queer women and trans people. For me, it is a level of intimacy, not one of tolerance.

Hend:

I am not a very fluent person. It is not a language thing – it is not about English or in Arabic. I often joke that the only language I am fluent in is anxiety. I stutter a lot; I hesitate a lot. The question that really got under my skin the other day was the personal queer revolution one, and I felt myself getting angry and a little defensive. Later, I had time to reflect on why my initial reaction was so visceral, raw almost. I think it has to do with the feminism part of the equation, the fact that queer was a word, or because I use them interchangeably. But calling myself something non-normative, I wanted to do that for a long time and felt like I couldn’t. I felt that I couldn’t own it because it was something that was out of my reach all the time, something that I almost didn’t deserve. So I wrote a little bit – not a poem, something less structured – about me wanting, imagining the concept of queerness like something I can wrap my head around. Something that I can keep close to my chest. Coming into this space, I felt that perhaps I wasn’t radical enough, that I didn’t have enough hope or energy to put in the work, to disrupt hegemonic narratives. But the past few days have opened up an avenue for me to reclaim things, for me. In that sense, I do feel that there was a queer feminist space that was created not only in this room, but also in what happens after we leave the room. We start to talk about our lives and get to know each other. It made me feel supported in a way that I have been lacking because of those inferiority complexes that I came with.

Momina:

The worst thing about social anxiety is that you expect other people to do the work for you, which is really unfair. Being in spaces like this you always expect kindness just walking in the door, and you do not know what that should look like. Yesterday, after workshopping my piece, Aya came up to me and said, “look at what you did.” Then she laughed and went away. And I said, “yeah, this should have happened earlier.” This should happen way earlier. And it wasn’t just the vulnerability or the tears or the sadness, it was also the laughter afterwards. I was looking for that kind of intimacy, and I do not know why I expect it from queer spaces, I don’t know why I expect other queer people to do that for me. It is very unfair, because we are all messed up and broken, and expecting other people to do emotional labor for you is fucked up. It is the reason I felt uncomfortable. The first few days, I felt alienated by things being way too academic, like Hend said, thinking that maybe this was not the right space to workshop a creative piece, maybe I was the odd one out, not being an Arab, not understanding regional politics, or just the casual Arabic you all throw around. But something definitely shifted yesterday. After we all left and Lara gave me her response to read. I was in my room, holding it, and I was like, “this is what I came here for.” I don’t know if this is the kind of feminist queer space that I want, I want more, as Jaha and Kawthar said, I want more. I don’t know what that “more” looks like. I do not know what I want, but what happened last night, more of that. More honesty, more vulnerability, more laughter. More affect, I guess. What this did to me though, it gave me a sense of purpose, with my writing. Archive was one of the questions, and I never thought of my writing as archiving, or my work as archiving, because I always think of it as imagining. I am not putting down or preserving anything. I am trying to create something, a history that I am not part of, or a community that I never feel a sense of belonging to, because of, well, me. We do a good job at erasing ourselves, but we also want to leave something behind because history keeps slipping away from us. At the protest I felt like “oh god, this is work, this is what real work is.” But then I also realized that if I can leave just this, just a poem behind, then that will be enough, and you all did that. You reminded me that maybe the little that I have to offer can be enough, so I am full of gratitude. Thank you.

Lara:

When we say space, I constantly think of the physical space, which depresses me. I felt detached from real life and the actual city, but at the same time being with all of you was worth it. I got sick of the hotel. Being part of the group was lovely, I got to learn a lot about this region that I had no clue about. I feel a bit ashamed of this, because in Turkey we focus on and aspire to Western European ideals and news, which conflicts with material life. Why do we want to archive? I mean we were here. We want everybody to acknowledge that we were here as mortal beings or as queer people. So it is totally worth trying to archive all of this, but I do not think it is necessary. We know that a lot of people were here before us and a lot of people will be here after us as well. I like this sense of continuity, I do not feel like there needs to be a proof to it all the same time. What has shifted? I think we feel more like ourselves when we are doing things together. “Let’s talk about this theory during lunch or let’s chat about Butler” – all these pretentious and weird ways of inserting yourself and your formation into the conversation, I despise them. But I didn’t feel that at all here because you weren’t like that at all, so thank you for that. What are queer feminisms? I have no clue. I am still puzzled by it, but it is about opening up spaces for each other because that is how I felt throughout these five days. We have all different perspectives about what queer feminisms should be or are, but this space, I would totally define it as queer feminist because it was affirmative, intimate, and open; I can share a lot and I won’t be judged, and I was surprised to see that. It really helped me to un-guard myself and let things go. I do not know Arabic but I could relate to some similar words you were using, which I appreciated because I was in super boring conferences and I hated and despised all of them. So thank you for not being those people I guess. It is like you have to put a lot of energy for these kinds of alliances and spaces to actually feel safe. And it was one particular and very special attempt to form alliances or to build solidarity.

Nour:

I am still very much processing the things I have felt during the workshop. I think I came here at my most physically and mentally exhausted, I am leaving even more physically exhausted but it hasn’t taken away from how transformative this experience was for me, the people and the intimacy and the relationality. This question of archiving, I found myself writing notes on my notes app about how I feel, because on a personal level I tend to write myself out. I felt I wanted to archive that because it produced these affective linkages between intimate, personal, and entangled archives, articulated through each of our discussion on how we feel, how we have come to understand and rethink things that have mattered to us, to our broader queer feminist imaginaries. I feel like it created a sense of continuity – being in a conversation with, rather than talking at or talking to, and I never thought of my own self and life as an archive, as something that I can relate to the broader archives. So this space has allowed certain connectivities and certain conversations to be had that would not have been possible elsewhere. And I really felt a sense of belonging that made it so much clearer how suffocating being in white academia is. I think this is what the workshop has taught me, that it is okay to be vulnerable and to think of myself as connected to these larger histories. The form was creative for me and then learning about all the forms that you have all used has opened up different ways of producing knowledge, where I do not have to write myself out. And also things like citation politics and different ways of producing knowledge. The more we spoke and engaged with one another, the more we saw how connected everything was on both the personal and the actual work that we were doing. I think we all inspired one another.

Kawthar:

I couldn’t help but go back to my own application and look into what my answer was to what queer feminisms are for me:

“In the days leading to the violent disbanding of the city of June 3rd, the moral panic over the presence of drugs, alcohol, and condoms in the vicinity of the military headquarters took on a more urgent tone. Sudanese took on social media to distance themselves and their revolutions from these acts of perversion. Some even requested the authorities intervene and cleanse the area of the sit-in. In a lecture delivered in 1975, the late Toni Morrison posited that the very real function of racism is distraction. In that vein, distraction can be understood as the marker of all oppressive systems. Queer Feminisms is an acknowledgement of the distractive tactics of oppressive systems, queer feminisms are a refusal to be distracted.”

If we look at the moment we are in, globally, it is a moment of upheavals, revolutions, revolts, people rising up to make their own demands. We are faced with a lot of calls that tell us “do not be distracted.” And that call is usually made towards the feminists, the women, the marginalized. This workshop came at a time where we feel that our politics are a form of distraction. So it really helped to come here, tell each other, and confirm to each other that we are not a distraction, that our politics, our visions, are integral for a socially just and equitable society. The themes we covered – diaspora, displacement, time and space, embodiment, etc. – point to our cohesiveness in terms of our politics. We did not need to have the discussion about LGBTQ identities vs queer for example. We are all beyond that and that has really helped a lot. And we also came in with our anxieties and apprehensions. We all started by saying, on the very first day, that we are imposters, that we do not have a proper academic background, that we have worries about our own identities and positionalities. I really love that one of the outcomes we all agreed on is that we should utilize this anxiety, this apprehension, and use them as a tool not just to guide us through the writing process, but also to guide our politics. If that is all we generated from this workshop, it is more than enough. One thing I really loved as well was that there was no attempt to come up with definitive answers to any questions. We are not here to say that we found the right path. Some of us are still confused, some of us still feel that there is more that is needed, and I echo that feeling as well. I want more. This workshop is a process, but it should not end here for us.

Jaha:

When I attempted to answer the question of what makes us want to archive this workshop, I simply put down, to remember. I would like to remember. I will be leaving with so many things that all of you have said that I know will be a part of me. I will be leaving with Momina’s rethinking queerness as something less lonely, with this notion of creating a history of yourself even if it is imaginative. I hope that by documenting this space, at the very least, we can honor these efforts. I am reflecting on what Ahmed has said about how theory has helped them unpack but didn’t necessarily tell them where to go from there. That intimacy, for me at least, makes the question of “now what?” a lot easier to approach, and a lot more manageable. Over the course of the workshop, there were a lot of moments where I doubted myself. There were times when I would go back to what I said and internally go through all of the ways it might have been problematic, because I still hold all these binaries in my head. I also share Nermeen’s sentiment that the question of queer revolution really fell heavy on me. In a lot of ways, I have had, or I exist in a form of in-between-ness that is difficult to articulate. For example, I am sort of working in academia, and I try to engage with decolonial theory, but I do not know the mainstream theory well enough to critique it. In my personal life, I am queer in a polyamorous relationship but I am married to my primary partner and it does not look queer to a lot of people. So I often wonder if I am really queer enough. I was telling Kawthar that maybe I am queering marriage. I feel a sense of affirmation to just be, to engage meaningfully and critically with the theories and the stories, to break binaries a little bit more, and to interrogate how I have internalized them. This space is a queer feminist space because we always interrogate the question, and constantly acknowledge anxieties and the tensions between solidarity and subjectivity. These are the conversations we need to keep having. But they also exist within temporalities and displacement and disembodiment and fragmentation. Totalizing the world, I think that all of its violence is because the structures are so rigid, so making room for in-between-ness is really important. Perhaps that is where queer feminisms situate themselves. I am very grateful to each and every single one of you for doing just that, and for allowing me to see you at a time when being seen can be a lot, when we are actively unseen.

Aya:

I didn’t think this space was something that could exist or even be replicated. There are specific experiences in my life that exist in their own temporality, in their own space, on a plane separate from the everyday. Some of those are revolutions, others are workshops like this one. Archiving comes from the sense that a lot is fleeting and our spaces are fleeting and our communities are disembodied in diasporas. That’s why there is such a pull for tangibility. I am making peace with the idea of movement, and that of yearning. A very long time ago I just stopped debating people – it feels like unnecessary work. When you are debating someone it is about proving yourself. So I had forgotten about what it feels like to have a productive conversation that is not an argument, to be able to confirm each other’s anxieties and to validate each other’s existence and how productive that could be for each one of us. I am a fan of writing, so being able to read your pieces and then talk to you is an incredible privilege. I feel like I have stumbled on a gold mine. It is one of those things that you do not want to go away, it is one of these moments that I know I will want to bring back when the going gets rough. What Ahmed was saying about bringing the magic back – not to be depressing but I cannot remember encountering magic. I remember wanting to or seeing others having that yearning, but in the little community space we have created outside of the planes of the everyday, we have harnessed some of that magic. What has shifted for me and for the group? I think we are all a lot more comfortable feeling out of space or like imposters. It is now a lot more like “maybe none of us should be here, or maybe all of us should be here.” One of the first pieces of advice that I was given was, “I want to hear more of you.” We erase ourselves even in what we produce. I think we are all trained to do that, and writing ourselves back into our narratives has been incredible. We became more and more certain of our frustrations because we have seen them bouncing back and forth – how we are sick of white academia, and then the moment when someone says, “So everyone is sick of white academia?!” I am the youngest here, so maybe I am not as frustrated as everyone else. Sometimes I feel that there is a punitive element in academia, as in, I had to study those people and so do you, just to prove that we can all do it, like generational trauma. So it is nice to witness ourselves go about our defensiveness because we preface ourselves with all these white people when we do not need to do so. I found this idea of queering structure really interesting. I always thought of academia and my intellectual type of interest to be very divorced from my poetry. A space where we are vulnerable enough to cry or to share very personal writing, and to queer space but also structure, is also an embodiment of us and our entanglement in this experience. What changed for me personally or for my piece, is that it has a sense of purpose and queer joy. What do queer feminisms mean to us now? I do not know if I can answer that question because I do not know what it meant to me when I came here. But this space is definitely what it looks like for me. So thank you for making that happen, for making the magic happen.