Queering Space: a Working Draft

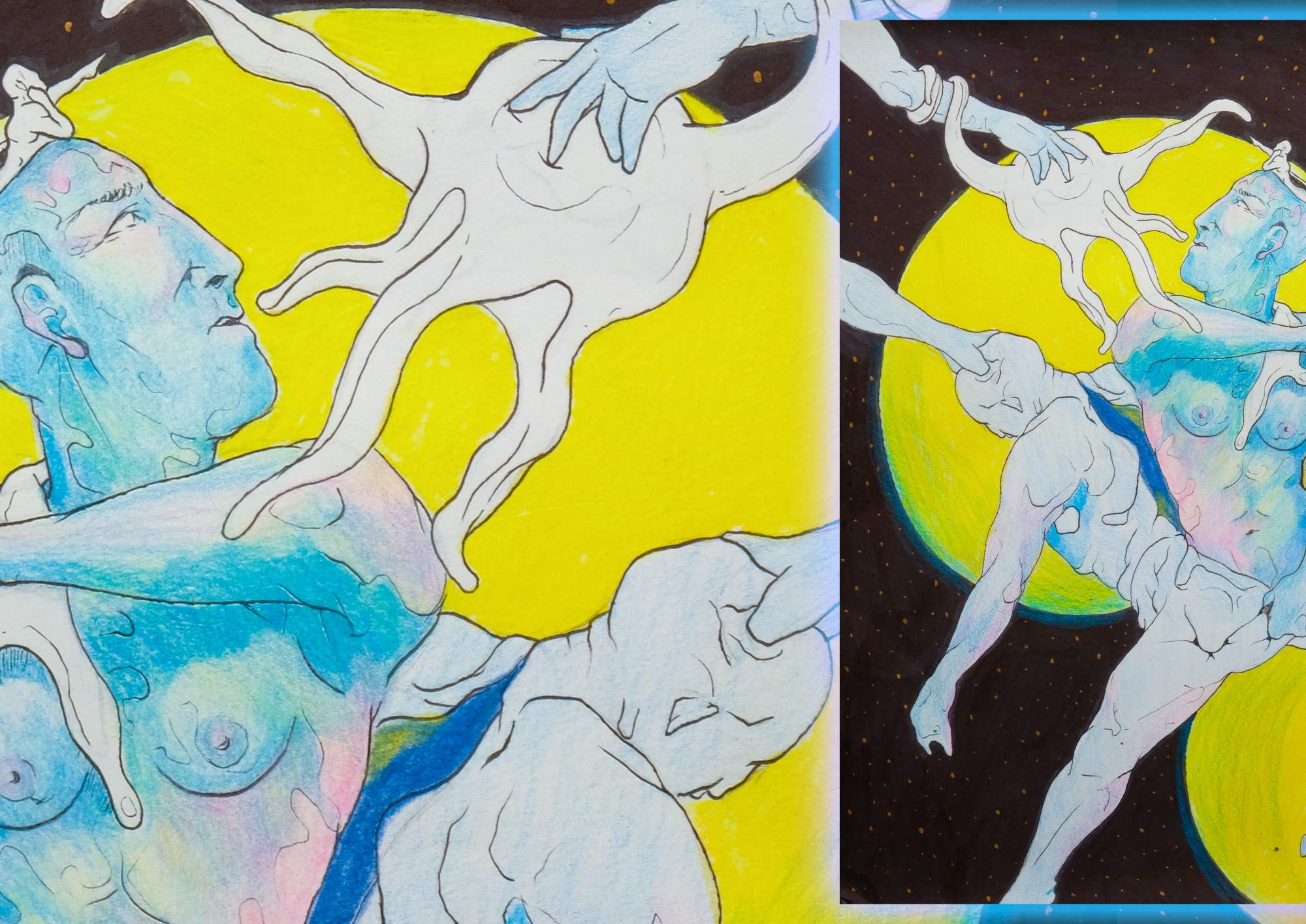

theod1_copy.jpg

star shedding its skin

Editor’s note:

This piece, written over fragments of time, is “unfinished.” By publishing it, we ask, what does a “finished” product do to our understanding of knowledge? When we judge a text as “ready,” what standards are we applying? What format, outlook, coherent ideas, and complete sentences can satisfy capitalist production? Often, our queer lives cannot find fulfillment in “clean,” proper, polished endings: to end a process is to seal our exclusion. To persevere in a process is to work towards dismantling what writes us off as fact. And so, not finishing becomes an embodiment of our knowledges that know no beginning and no end. We are the process of it.

Kawthar and Jaha are in conversation with each other and with all of us. Their imprint is all over the issue. Publishing this process wherever it reaches at the time when “final” drafts are due is a commitment to archiving us. It is a celebration of their lives, of our respective and joint liberations.

abstract

This essay is the outcome of an ongoing conversation between two queer friends from Sudan: Kawthar and Jaha. It explores the queer uses of space to the backdrop of the Sudanese revolution. For months, the sit-in at the doorstep of the Military HQ in Khartoum, where hundreds of thousands of revolutionaries congregated to set out their political demands, served as a political and cultural hub. Stratified social codes appeared to have been suspended, and vibrant forms of resistance – long suppressed by the Islamist military dictatorship – flourished.

It is important to stress that the daily resistance practices that became apparent to the public during the sit-in had always existed, often in plain sight. However, these non-normative modes of being were rendered invisible and pushed to the shadows by the same oppressive structures that labeled its practitioners as the deviant “other.” This duplicitous approach – invisibilised yet visible – birthed a space for many queers to exist under the guise of “plausible deniability.”

Using a queer feminist framework, which equates queering with acts of daring resistance that disrupt norms, we contend that the sit-in escalated and networked existing daily resistance practices, and therefore constitutes a “queer use” of space (Ahmed, 2018).

Grounded in this conflictual relation to the “norm” and the normative, and the historically contentious relationship between the centre and the margin in Sudan, we argue that the emergent calls by LGBTQ Sudanese for acceptance and visibility in the public sphere should not be separated from calls for a transformative political organising that foregrounds emancipation for all “others.”

Through this conversation, we try to hold (space for) each other, as friends, to process the onslaught of emotion that is going through a revolution that somehow manages to radically challenge so many norms, yet place queerness at its very margin.

intentions

|

I hope this reads as an extended conversation with prolonged silences in between. I hope it feels like catching up with a friend. Because it is. I am riddled with anxieties; I don’t feel definitive within my voice written: writing can feel like an act of erasure. I hear the voices of other queer people whispering into my ear: I was there too. I lived through this. This is not how it happened. |

I start apologising: I am so sorry, love. Please come join our conversation. We’re telling each other what happened. It all only happened in retrospect. I am writing this to reach out to you. I hope it reads as an invitation. Come sit with us.

|

|

Khartoum

|

queer space in revolutionkawthar It was a speculative call, one that willed us to draw upon our imaginations, to work against a belief that the existence of such a space is unthinkable. Perhaps we could be excused for believing that such a space is unthinkable. The ability to perform imaginative work is after all a form of resistance. And our belief in the impossibility of a queer Sudanese space cannot be separated from various contextual factors. Sudan’s islamist military dictatorship was nearing the end of its third decade in power, and there’s a dearth of archival material on non-normative sexualities in Sudan. But to return to that conversation, we got lost in the particularities of the question, and the visions it evoked: the types of tapestries, the colours and fabrics. The geographies and the sights and the sounds. Essentially, the physical dimensions and corporeality of such a space occupied a large part of our thinking, that it distracted us from the quite obvious: that in sitting there, at a busy intersection in the middle of Khartoum, and envisioning a queer space together, we had in fact created a queer space. jaha But I think daring to think “queer space,” for me, began before we were sitting on that roundabout imagining a queer commune. That came later, as a more elevated, detailed, and radical vision of existence. I couldn’t have started there. For most of my life, queerness was a whisper in the back of my mind. There were nights of course, there are always nights when you meet yourself away from watchful eyes, but I could never take her with me to the light. One of those nights, I created a fake twitter account, searched black+queer and found you. I think the concept of a sudanese queer space began for me when I discovered that you’re sudanese. Perhaps we begin to hold space for ourselves as early as this basic level of recognition, of realising that you’re not alone. Perhaps the creation of queer space begins in stepping away from your individual journey with queerness so to speak, and realising it is a collective journey. I kept thinking of our conversations about a queer femme commune during the months of the sit-in. It was so compelling and magical how this dream of space began to feel like a physical lived collective reality. The bullets could not penetrate what we had, nor could all the state violence and horror. We had each other. There were many parallels between this ideal of a queer commune and the literal spaces of political protest and sit-in sites. kawthar I’m not sure where and how this sense of fragmentation originated, but I remember that it grew more persistent with the start of the Sudanese revolution. I can attribute this sense of fragmentation to the conflicting emotions of being aware of how I was physically distant, yet feeling somewhat present thanks to all the videos and images that were being shared; feeling fearful, yet knowing that I was safe. And as the revolution progressed and the protestors occupied the spaces adjacent to the Military HQ, spaces which soon turned into vibrant sites of political and cultural production, I began to feel excluded from the emerging narratives and spaces of Sudanese queerness. I felt that, in not being able to actively engage with/in these spaces, I somehow fall short. jaha There is a clear tension that emerged at the recognition of queer demands, queer imaginaries, and queer political action within the revolutionary movement at large. There were moments when the visibility of queer voices (mostly behind nameless online accounts) triggered friction. I saw all these radical leftists whom I previously admired silence the sounds of queer people who were actively participating or making themselves more visible within the protestors’ mass, under the usual guise of “it’s not the time yet to bring these issues forth, you’re going to alienate us more from larger society.” What was especially disappointing were the undertones of “how dare you infiltrate this movement? how dare you pollute and degrade it with your queerness?” I may be too proud to admit it outside of an intimate conversation such as this one, but that was truly painful. Another thing I would fear exploring outside of the safety our own little sudanese queer space is my frustration with how the visible demands of queer persons often mirrored western liberal ideals of recognition and inclusion into a flawed, often exploitative, system. It entailed things like arguing for our existence based on principles of personal freedoms and demanding recognition from the state in marriage institutions as an example. I cannot claim that these aren’t important things for a lot of people. After all, we have the death penalty hanging over our heads for seeking intimate unions. However, such discourse is divorced from material realities on the ground, from our deeply communal society. I don’t know if I feel included in either the homophobic leftist spaces or the liberal queer narratives. kawthar This act of renegotiation happens both within the enclosure of the boundary, as well as between those who dwell within and outside the boundaries. As you have mentioned, the boundaries that queer individuals in Sudan enclose around themselves is heavily armed with modern, liberal discourses on sexuality. It’s a boundary that calls for pride parades and gay marriages. It’s a boundary that calls for acceptance and legalisation. For example, I recall a Facebook page that you had shared with me, that argued that lesbian women should be accepted and accommodated within feminist organising spaces. Underlying the post was the assumption that acceptance was the be all and end all of queer Sudanese people’s struggles. That queer individuals are somehow removed from the larger context they exist within, that their struggles exist in isolation of their society. What does it mean to advocate for lesbian rights in a context where any sexual relation outside the rubric of marriage is criminalised? What is gained from accepting queers when the environment does not provide the necessary groundwork for a viable life? jaha To further this inquiry: how do we begin to articulate what we want then? How do we unravel our own demands that are not borrowed from somewhere else, and how do we begin to fight for them? There must be room to build a discourse that recognises how our parallel movements can actually intersect. A conversation that is founded on the notion of personal freedoms is perhaps less useful than one grounded in bodily and sexual rights that brings together so many people under its banner, so that as we demand for our intimate unions we also march as feminists to end the injustice and violence within marriage institutions, so that we engage and critique the role of patriarchy, colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism in our struggles. So to me the question of queer space in revolution is a layered one: it is us being in conversation with each other and the imaginative world-building work, it is the physical spatial dimension of our existence in protest, it is trying to project our voices over the borders and violence that locks us out, it is the building of a narrative that harbours solidarity and responds to material contextual realities. But ultimately, queer space in revolution is about posing the question: what does a queer Sudanese revolution look like?

existing within plausible deniabilityjaha There are entire alternate lives thriving under the nose of Khartoum, its Public Order Police, and the dominant dogmatic narrative of the city’s identity. People existing outside the normative engage on a daily basis in practices of renegotiating the borders between public and private spaces, creating new rules of recognition and relating to each other, and on occasion using the same tools the system uses to control us in order to create more cover and protection. Queer people share those spaces with many others; we share them with women attempting to meet friends and stay out late without harmful confrontations with their families, we share them with people who drink or smoke alone or with loved ones, we share them with non-queer lovers who dare touch one another without state and societal approval through marriage. What takes place here is not a struggle to gain recognition; more often it is the opposite. It is a struggle to carve space to exist in the here/now, while avoiding the state and society’s scrutiny. The irony is that sometimes these non-normative modes of being are rendered invisible by the same oppressive structures that label us as deviant “others,” and condemn us harshly. In doing so, they don’t recognise us, or they trust their policing and their dogmas to rid our imaginations of such images. These non-normative forms of being are sometimes so otherised, that they become unthinkable. This duplicitous approach – invisibilised yet visible – birthed a space for many queers to exist under the guise of “plausible deniability.” I remember months ago when I had written to you in a panic thinking I had been outed to an older male colleague who might have overheard a conversation I was having. You assured me that I still existed within “plausible deniability.” That really stuck with me. I remember using this during the anxious moments before the beginning of a protest, when you would look around and recognise defiant faces around you in public. You can tell they might be protesters too, but they could also be security agents. When a random older man, likely a security agent, asked me one of those times as I walked past him: “you are one of them rioters, aren’t you?,” plausible deniability was that gray area: a daring and challenging space where it is difficult to criminalise you but also hard to miss the mischief. But there are also those of us who cannot “pass.” Those of us who cannot afford access to those safe private spaces. Those of us who are loudly “other” to the normative gaze. Those caught red-handed that bear the brunt of the violence. All of this stops me in my tracks when I try to explore this state of plausible deniability. I am not sure what I am getting at. I think I just marvel at the focus on recognition, when my experience has been a constant attempt to carve out space for myself and finding plausible deniability as a platform where this dance with the system takes place. kawthar So the state’s violent attempts at policing and purging our imaginations are an extension of its efforts to rewrite the official archives of Sudan’s history. And that erasure is in itself a form of violence. Over the years, I’ve made numerous attempts to excavate archives for histories of fluidity, accounts of divergence, stories of deviance but have come up empty for the most part. And that inability to forge connections to a past, to find continuity – however tenuous – has always felt like a violent erasure. Admittedly, my search into the archives is constrained by the fact that I am only looking into written archives. And with the shift towards embracing an Arabised and Islamised narrative of Sudan, the custodians of the written archives cannot be entrusted with preserving histories of transgressive practices. This is particularly true when it comes to accounts of Sudanese women’s sexualities: the prevalent narratives continue to focus solely on stories of circumcision, early marriage, assault and other forms of violence. But we do not hear of the everyday resistance practices of women, how they interpreted and interacted with contemporary events, how domestic practices shaped (and were shaped by) political events. These narratives can be traced from the everyday and seemingly unremarkable: the songs women wrote and danced to during weddings, the names given to popular dishes or outfits. Exploitation:

escalation of the everydayjaha The revolutionary momentum then was so transformational that its effect spilled out to other parts of the city. It suspended norms, expanded room for otherised identities beyond queer genders and sexualities: from the stoners at the marginal site of the sit-in that were later dubbed “Columbia,” to non-fasting groups openly taking the day shift to guard roadblocks and barricades at the border of the sit-in site during Ramadan, to relaxed scrutiny of state and society alike, to every other honest way to being in public; not without occasional tensions, but certainly with generous coexistence, way more than I could have imagined at the time. I don’t want to claim the sit-in was a utopia, however. There have obviously been some serious challenges. Notably, many incidents of sexual assault and harassment, misogynistic chants and behaviours, among other things. But in the absence of normative rules, there was room to correct the course, and to engage in meaningful collective dialogue on these issues. One of my favourite things during the Sudanese revolution are the revised chants, like “الترس دا ما بتشال الترس وراهو رجال”, being swiftly transformed into “الترس دا ما بتشال الترس وراهو ثوار”. To me, the key factor which supported such a large reclamation of space has been the cooperative means of sustaining this huge mass of people. The fact that everyone had access to food and shelter, and it was everyone’s responsibility to ensure it. This fact is often celebrated by way of showcasing Sudanese hospitality, charity, and philanthropy. I find this a problematic framing. It is important to acknowledge the economic system that thrived during the sit-in and revolution at large as a crucial foundation to replicating that momentary experience of freedom. I know that for our society, the commons are crucial to how we survive, how we have survived for as long as we have despite hardship. I finally realise now what it looks like amplified beyond direct kin or neighbours. I realise that it is not only the suspension of oppressive norms towards expanding personal freedoms that was revolutionary. It was claiming our collective responsibility to feed, house, and protect all those framed as “others” for so long. kawthar And of course we cannot think of queer spaces without considering the inhabitants of such a space. And most importantly, we must interrogate the relationship between the space and its inhabitants. Who must be present in a space for it to be considered a queer space? Whose presence must be excluded? Perhaps the narrative of the sit-in site within the revolution cannot be seen as parallel to the narrative of the city of Khartoum as the land of hope and opportunity.

|

|

Beirut |

[dis]placing center/marginjaha kawthar jaha So to me entering queer theory and queer politics means that we further target the categories to a point where they're not necessarily – I don't want to say “relevant,” but where we can transcend them and also go through them. The argument is not about asking for inclusion, like include the marginalised women within feminist spaces, and that includes the feminist spaces within the mainstream political spaces. So, it's more about, kawthar jaha kawthar

the death of revolution is the death of imaginationjaha Then the terror in the streets for weeks after; the shock; the mourning; the heartbreak. As a result of the violence and compromises that followed, we still live under military rule with a civilian executive government that has very conditional powers, closely watched over by men in uniform. The idea of queer(ing) spaces feels so bleak to me these days. Every time I come here to write something about it, I am reduced to a puddle of tears. Is it the revolution in all its glory being thinned out to more of the same, or is it my own self coming to a reckoning? When we wrote the abstract, I felt very different. It is not just that I had hope; I was living through a miracle. I had the guts to claim a life that was once a dream. What came into reality was existing within loving and rebellious communities; increased freedom of mobility and autonomy; expanded space of influence and voicing collective demands; effortless fluidity of sexuality and attraction; there were no contradictions, no either or, no binaries. Now, after the heartbreak of June 3rd and the slow death, or rather poisoning, of the revolution, I feel the walls closing in. How do we make room for this as an authentic part of our narrative without being crushed under its weight? For the pain and despair of it all, for the shutting down of imagination… I have never felt more queer than now, often in the literal sense of being too “out of place.” kawthar Imagining a liberatory future and envisioning new modes of existence is preceded by a recognition that the status quo cannot continue. "I want more," is a refrain that I often repeat to myself. What that “more” encapsulates is almost impossible for me to imagine. I've struggled for years to imagine a queer future: a future that isn't a “prison house” (Ibid.); that isn't “more of the present.” We may not have a clear vision of what a queer Sudanse space would look like, let alone a framework for how it may be actualised. Makes me think of “more” as a mental sharpie; a reminder to “uncap what’s inside"

queer afterlives

|

Ahmed, Sara. (2018). “Queer Use.” feministkilljoys. 8 November. Available at: https://feministkilljoys.com/2018/11/08/queer-use/

Muñoz, José Esteban. (2009). Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. NYU Press.

Siddiqi, Ayesha A. (2015). “every border implies the violence of its maintenance” [Tweet]. Twitter. 2 September. Available at: https://twitter.com/ayeshaasiddiqi/status/639054385797038080?lang=en