Queer Curatorial Praxis: Learning from Failure at the “Queer” Asia Film Festival

This article draws on over four years of curatorial work at the “Queer” Asia Film Festival in London to navigate the ambivalences and affective journey articulating a queer curatorial praxis. It theorises the failures in curation of a queer film festival focused on film and video from various parts of Asia, Africa, US and European diasporic communities, and South America as an important engagement with an anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-nationalist praxis of curation. Drawing on the work of scholars and practitioners of third cinema, film festival curation, queer theory, and affect theory, it offers a practice-based epistemological navigation of the structural impediments affecting the curation of film at the intersection of queer and Asia. It reformulates the question of queer practice and curation as responsive, ethical, caring, and committed to a decolonial queer politics.

If curation is defined as a process composed of editorial, selection, and programming (Rastegar 2016; 2012), what and how can we define queer curation located in praxis? What are the negotiations between a queer politics in praxis and the pragmatics of exhibition and curation at a queer film festival? In this article I negotiate my understanding of the politics of queer curation in the practice of curating the past four iterations of the “Queer” Asia Film Festival in London, from the inaugural one in 2017 to the first digital-only edition responding to the pandemic in 2020.1 I situate my work as a scholar-curator and theorize the failures of this curation as a complex node from which to strive towards a responsive queer curation vested in solidarity and care, and in enabling further south-south collaboration.2

In navigating curation as failure, my aim is to understand, theorize, and contextualize the structural questions that impose limits on framing a festival as expansive as and yet as liminal as “Queer” Asia.3 The structural impediments that I see as central to the failure in curation emerge from the continued liminality of the epistemologies afforded by the commingling of queer and Asia (Martin et al. 2008; Chen 2010; Arondekar and Patel 2016). This liminality and the impediments in the case of the “Queer” Asia Film Festival include the impossibilities and hierarchies perpetuated by the UK Border; the larger questions of queer curation and knowledge extraction in relation to borders; and the national, racial, and gendered logics that inform audience viewing practices and self-selection. Together, these reflect the urgent need to rethink a queer curatorial praxis that grapples with the continued colonial dynamics affecting festival curation. It also requires holding curatorial praxis accountable to queer and decolonial solidarity. That is, I ask whether curation can work strategically to challenge the colonial dynamics of film exhibition and cultural consumption; and the structural barriers that, in setting such a process up for failure, offer important lessons.

In this account of failure, I retrace the changes in my curatorial strategies as the festival founder and director that, to an outside viewer, might appear as “successful” but highlight my difficult affective encounters with systematic and structural colonial dynamics. I see retracing failure as an important methodology in encountering structural barriers that at the time of encounter seemed overwhelming. It prompts asking why curation fails and how can it challenge the “dichotomous valuations of film … and facilitate ways of looking that allow for difference rather than enforce nationalist models of homogeneity” (Rastegar 2012, 310)? These questions also address the continuing prevalence of “area ghettos” (Jackson, Martin, and McLelland 2005, 301) that shape subjectivity and knowledge production. Retracing failure is an important countering strategy that sits with the dissipating affect of ephemeral festival work; their outward appearance papers over deep rifts in curatorial strategies; and the extensive labor demanded, always in-the-moment, to navigate the racial, classist, and colonial logic that perpetuates structures of inequality remains undocumented as practice takes up all available time and energy.

Within these contexts, I define my queer curatorial method as a politically charged radical process of editing and programming for audiences that contributes to actively shaping transnational queer film cultures; it eschews prevalent and hegemonic notions of quality and taste; and is keenly engaged in countering the colonial dynamics and global flows through which this festival has come to be. This is especially important given the continued nationalist and/or fascist legacies of film festivals in Europe (de Valck 2007) and in various countries in Asia (Rajadhyaksha 1985; Diaz 2012; Hagedorn 2013).

As a note from the outset, the vision for the “Queer” Asia Film Festival has been something I have driven since its inception in 2017. I have been supported by a small curatorial team drawn from the “Queer” Asia conference committees over the four film festivals. The last iteration during the summer of 2020 over the COVID-19 pandemic demanded committing the curatorial praxis to respond to the crisis, recognizing the differential impact of the pandemic and the effect of continuing precarity. While mapping the twists and turns in the failures of the film festival’s curation, I realize these may not be a view shared by other curators or partners who have been involved over the other years of the festival. I don’t offer many answers to the many complex questions raised by the structural barriers impeding curation, and see them as an invitation and contribution to many rich conversations between community organizers, activists, and theorists.

2016: From Small Post-Graduate Conference to an Urgent Site of South Centric Work

As one of the four people who initiated the “Queer” Asia conference in 2016 in London, I was looking for a way to navigate the isolation I felt in doing queer work in Area Studies by building a small community. We imagined the first “Queer” Asia conference in SOAS, University of London in June 2016 (Luther and Ung Loh 2019; Simpson 2017) as such a space. However, the response and participation far outstripped our plans. What resulted was an intimate setting bursting to its seams. Participants included academics, activists, performers, and filmmakers and led to a vibrant atmosphere of meaningful and empathetic discussion, debate, and networking.

We also programmed films and performance as part of the conference. As with the discussions following the panels, the audiences watching the films and performances were also keenly participant, engaged in meaningful dialogue, and brought their experiences and knowledge to the screenings. The vibrancy of that unique milieu, a kaleidoscope of perspectives, planted the seeds for the annual “Queer” Asia Film Festival.

This milieu was enabled in part by the goals and strategies of “Queer” Asia which included fostering dialogue between the different contexts within Asia in an inclusive and understanding environment (see Luther and Ung Loh 2019, 2-3). However, in hindsight, the commingling of a kaleidoscope of perspectives at the screenings in 2016 enabled a subversive practice in cinema tied to the relationship between audiences and film (Gabriel 1979, 89).

It was this that prompted my work in initiating the “Queer” Asia film festival in 2017. The film festival was oriented towards building a south-south solidarity that would share an understanding of the ways in which differences were subjugated to new bourgeois patriarchies, nationalist notions of post-colonial modernities, and neoliberal production and consumption practices. However, reflecting on complexities of curating of a queer film festival focused on the global south in London also raised important question of location, decoloniality, and a radical queer praxis. I often found myself turning to theorists of Third Cinema including Teshome Gabriel (1982), Ella Shohat and Robert Stam (2013), and Glauber Rocha (2019) amongst others to understand the responsibility of festival curation to a decolonial and radical queer praxis.

Gabriel argues that film made in the Third World is not sufficient criteria for it to be radical; rather, it is “the ideology it espouses and the consciousness it displays” (1982, 2) that orients it as Third Cinema. He calls Third Cinema “that cinema of the Third World which stands opposed to imperialism and class oppression in all their ramifications and manifestations” (ibid.). Radical praxis in Third Cinema implies connecting it to the revival of Marxist film criticism and ideology in the 1960s and 70s which draws on the work of Althusser (1971), Gramsci (1978), and Fanon (1967) amongst others. However, Third Cinema practitioners differ in their understanding of such radical praxis. For example, Jorge Sanjines (1970) and Miguel Littin (1971) argue that revolutionary cinema must be oriented towards a call-to-action; differing themselves on its extent. Others, such as Ousmane Sembene (1973), see cultural consciousness raising as the end goal.

Film production in many parts of the global south has, since the late 20th century, been through many shifts and processes of rationalization of production and ownership. Hindi cinema, as an example, reflects these shifts, as the revolutionary and working class (peasant) oriented cinema (Prasad, 2000) gives way to bourgeoisification and gentrification (Ganti 2012). Film consumption, distribution, and exhibition too has gone through several transformations (Ganti 2012; Dwyer 2011) including privatized consumption or at expensive multiplexes, and consumption on hand-held devices (Dasgupta 2017). Cognizant of these shifts, nearly half a century since Glauber Rocha outlined third cinema as a “cinema of liberation” (1970), the question that then arises is: can exhibition and curation channel a radical oppositional ideology building a counter-cultural consciousness between audiences and films? Particularly, can the exhibition and curation of film positioned for consumption as “queer” be oriented towards a call-to-action, and if so what kind?

Gabriel suggests alternative practices of distribution and exhibition, such as the Pan African Federation of Cineasts (FEPACI) or Argentinian Cinema de la Base (1982, 23), which share similar goals of building solidarity and following production/distribution/exhibition practices that that resist bourgeois and imperial consumption. However, these are complicated examples to think about in relation to queer film today. Not only are queer filmmakers stratified by nationalisms and separated by global flows of culture and people oriented north-ward, but they are also curtailed by legacies of colonial and nationalist homo, trans, and queer phobias. Navigating these imbricated inequalities through the “Queer” Asia film festival while recognizing “the situated nature of audiences and the contingency of film aesthetics” (Dovey 2015, 93) is what I am calling a queer curatorial praxis.

2017 - 2018: Failure as a Means Towards a Queer Curatorial Praxis

The first and second annual “Queer” Asia Film Festivals in 2017 and 2018 rapidly grew in scale and proportion. In 2017 we screened twenty-one films, and thirty-three in 2018 (and over eighty in 2019 – more on that later). The festival was free to attend, located in accessible venues, and tickets “sold” (all free) grew from five hundred in 2017 to over thirteen hundred in 2018. Objectively these numbers show an exponential growth. However, the numbers mask the extensive decolonial and queer labor of the curatorial team.

The other significance masked by these numbers is in the fact that our festival centers film and video from different parts of the global south. This focus is a rarity amongst LGBTQ+ film festivals (Rhyne 2006) especially as LGBTQ+ filmmaking is underfunded and faces socio-cultural and political opprobrium and hate. For example, filmmaker Fan Popo needed to undertake crowdfunding, support his work through day jobs and translations (Popo and Hongwei 2019), and take on casualized work to make his films (pers. comm., April 14, 2021; also see Deklerck 2017; Bao 2019; Jacobs 2020). Similarly, filmmaker Faraz Ansari resorted to “guerrilla filmmaking,” shooting without permissions and often fleeing police, on the Mumbai local (pers. comm., Jun 29, 2018; see also Seth 2018). Such narratives are common amongst directors recognized by mainstream film cultures such as Maryam Keshavarz’s Circumstance (Keshavarz 2011), produced under a fake script in Lebanon (Khaleeli 2012).

Therefore, curating work from across the global south requires an extensive labor of care. Such care requires understanding the constraints within which film is produced and materially supporting their work. This is the first step towards a queer curatorial praxis. It treats film and video not as a finished cultural product, but as a fragile collection of struggles brought into being by an extensive and collective labor. It stresses the urgency of remaining means-aware – that is, recognizing that filmmakers often cannot afford to pay submission fees to festivals, afford visa costs, or take out time from their work commitments (often casualized and precarious) to seek out festivals and submit their work for exhibition.

I define a queer curatorial praxis as one which is actively engaged in the work of exhibition and distribution, while remaining invested in an ethos and in processes that are attentive to the context-specific hetero-patriarchal structures within which queer filmmaking is constrained. A decolonial, pro-active, and supportive praxis-based approach to curation responds queerly with an empathetic duty of care. It also, and this is significant, reflects the need for a dedicated commitment to reaching out and communicating with makers of queer film and video from a plethora of contexts and backgrounds not necessarily reflective of the backgrounds of the curatorial team. Such measures need to be attentive to different languages and sensitive to understanding queerness in different contexts without reproducing western queer epistemologies either. It also requires thinking-through exhibiting films and performance for an audience in a manner that resists the replication of an imperial gaze. On a practical level this involves working to ensure that filmmakers or their teams were being supported in presenting their work, or conversations around their work center and privilege their voices without appropriation. At times this also means undertaking additional work to fund-raise to sponsor their visa, flight, and accommodation costs where possible to avoid ventriloquizing and remaining mindful of the intersection of the politics of representation and location. In all instances queer curatorial praxis needs to be reiterative and reflexive.

Given these considerations, in 2017 and 2018 we worked with meagre budgets raised through crowdsourcing and small funding proposals to universities. Often, we actively used digital technologies when supporting a filmmaker to travel was not viable due to our limited resources, or afflicted by visa regimes.

A significant part of the challenges we faced was the impervious UK Border. It forms a structural barrier to our negotiations between queerness and curation. With the success of the 2016 conference came a heightened and active global engagement and participation; most often it also meant more difficult encounters with the UK Border. Our 2017 festival, titled “Desire, Decolonization, and Decriminalization,” marked increases in participants, especially from outside of the UK. People, working in various parts of the global south, reached out for support with the prohibitive costs of a UK visa.4 The long litany of paperwork that this visa application demands raises complications for queer and trans people who are unable to apply for legal documentation given the transphobia, homophobia, and various forms of gender, sexual, class and caste-based, religious, and nationalist frameworks at work in official and financial documentation. Our curation responded by stepping up our fund-raising activities. We hosted further crowdfunding activities and produced support proposals and impact documentation for universities to grant us funding tied to specific speakers or participants. All extremely labor intensive – yet also REF/TEF related dead ends for all of us already working in precarious ways within UK academia – but extremely vital to the survival and support of queer people of color.5 It also implied a painful process of accounting for visa processes, and worse still, visa rejections, in our curation, such as difficult decisions on allocating meagre resources and time.

In cognizance of these difficulties that had become glaringly obvious to us, and the mounting vitriol and continued demonization of migrations born of global north imperial projects and colonial legacies, we themed the 2018 festival and conference around “BodiesXBorders.” However, despite our best efforts and support from established academics, our list of visa rejections for applications had grown intolerable. Out of frustration and in response, we added an installation to the 2018 art exhibition that foregrounded our list of rejected visas from queer global south artists, practitioners, and filmmakers.6 This included a protest letter that participants could sign to send to the UK Home Office.

The film festival curation encountered further difficulties; by 2018, it was part hosted at the British Museum through their Community Partnerships Team. Tallying rejected visas and exhibiting in a prestigious – precisely because it is also a colonial – UK institution imposed difficult limitations on our program.7 On the one hand, it increasingly meant more practitioners sending us their work; on the other, because we were partnering with the Community Partnerships Team, we had to rely on the charitable outlines of the museum, including applying for film certification. However, access through this team meant a free venue enabling us to divert funds towards practitioner costs. We also tried to maximize the films we screened in the limited duration of free access to the museum, balancing the venue’s (accumulated) cultural capital and transferring its cultural legibility by association to filmmakers.8 All this was coupled with the usual work of building audiences, marketing the program, and running the festival on the day.

I found it particularly difficult to overcome two aspects of this labor. First was the question I was repeatedly posed, usually by white people, of, “what is worth watching?” The second, even harder, was what I had started noticing as racialized, gendered, and national context-based audience self-selection across our festival.

“What is Worth Watching?”: The Politics of Location and Queer Curation

Roya Rastegar rightly notes that the question of quality and taste is ideologically charged and threatens to restrict film and film cultures. She says, “[e]xclusionary characterisation of quality enforce conventional paradigms of valuing cinema” (2012, 311). These replicate a binaristic relationality between arthouse and commercial cinema (de Valck 2007) without considering what is theorized as “Third World Cinema.”

Given step one of the queer curatorial praxis (care), the question “what is worth watching?” is one of epistemological violence (Hall 1996, 446; Spivak 1988). It indicates that the process of curation is not an adequate measure of “worth” (see Hall, 1996, 449) and belies an expectation of aesthetics and refinement to the films being programmed. Moreover, at best, this question belies an ignorance and disregard for the processes whereby a cultural product is/was worthy/unworthy of being consumed within the UK Border while the presence of practitioner is not considered. Hall critiques such questions of worth, arguing that they cannot be resolved by “transcendental, canonical cultural categories” (1996, 449). Instead, he suggests we think from a position which “locates itself inside a continuous struggle and politics around black representation” (ibid.) (emphasis original).9 I interpret this position of continuous struggle as the second step in working towards a queer curatorial praxis.

Drawing on practitioners and theorists of Third Cinema, I would often respond to this question to suggest that meaning be made in the process of spectatorship. Gabriel argues that “[s]tyle is only meaningful in the context of its use – in how it acts on culture and helps illuminate the ideology within it” (1979, 89) (emphasis original). What aesthetics of film have been standardized by Western queer film and their production value in the twenty-first century, and how that shapes our subjectivity, are pressing responses that need to be brought to bear in asking “what is worth watching” at a festival that centers film and video from the global south.

Theorists of Third Cinema have navigated this question of worth and style in synthesizing a range of different radical practices in filmmaking. Gabriel suggests that such films develop a new film language that engenders a decolonization of the mind and a radical transformation of society (1979). However, as Anthony Guneratne points out, the question of style and film language seems to be a “superficially illogical requirement” (2004, 11) as postcolonial audiences and filmmakers are also interpellated within “a larger sphere of capitalist consumerism” (ibid.). Moreover, as Shohat and Stam (2013) have shown, the global cultural flows sustained by inequalities in access, production, and consumption imply a Hollywood-centrism shaped by industrial and market practices. This is further complicated by the question of gender, sexuality, and queerness. Guneratne argues that the marginalization of women within Third Cinema is complicated by the inequality of access to power and resources (2004, 17), making it much harder to make film that is not geared towards either mainstream Industry markets (de Valck 2007; Kredell, Loist, and Valck 2016), or markets and production practices attached to film festivals (Iordanova and Rhyne 2009; Iordanova 2015). For queer-identifying filmmakers, access is then further stratified depending on the contexts and conventions within which they are working.

I raise these issues to reflect on the immense contradictions and complexities at play in thinking through what a question of value or worth means in relation to a queer curatorial praxis focused on the global south. I juxtapose this question of worth with B. Ruby Rich’s reflection on the gritty grainy aesthetics of New Queer Cinema – inflected as it was by postmodern pastiche, appropriation, activism, and politics – to highlight the superficiality of the question of worth in relation to queer cinema in the global south. Rich called the aesthetics of New Queer Cinema, a kind of “Homo Pomo” (2013, xvi) style of film-making. New Queer Cinema as a “moment” (2013, xv; 2000) in time was also affected by the AIDS crisis, particularly in the global north, the rise of Regan and Thatcher era conservatism, and technological changes in video and film through the camcorders and hand-held devices. Stylistically, it was also a cinema that was born out of the particular queer urban milieu of protest and anger made all the more possible by the urban geography afforded by low rent pre-gentrification New York or London. Rich traces the aesthetics of this cinema as it moved from the basements and underground screening venues to the mainstream; as audiences at film festivals chased and demanded more normativity that came at the expense of the queer, the outrageous, and the rebellious; and as industry stepped in where there was money to be made. If New Queer Cinema, as a collection of pastiche, appropriation, anger, and activism is afforded a place in film culture – and was a challenge to questions of taste and quality within prevailing film cultures and aesthetics in the 1980s and 1990s – then it is even more important to pay attention to the structural question of borders, nationalisms, and racial boundaries. These structural barriers limit queer cinemas everywhere and their access to similar considerations that suspend notions of aesthetics and taste informed by neoliberal capitalist media consumption. Especially as the AIDS crisis rages on in the global south (Murtagh 2019; Cohen 2005; Hallas 2003), queer and women filmmakers continue to face impediments in access and resources, and multiple and successive fascist and nationalist governments continue to suppress and deny queer sexualities and genders.

The commingling of structural factors – low rents, urban queer populations, onslaught of the conservative governments, the AIDS crisis, and technological change – enabled the emergence of what subsequently got termed New Queer Cinema in the 1980s and 90s. These coupled with close ties and porous borders within the global north enable a queer bitter-sweet spot, as it were, for the emergence of a radical queer film culture. Certainly, what makes the cinema of that “moment” (see also Rich 2000) worth watching was its ethos of social, cultural, and political repression rather than the capital (or lack thereof) invested in it. However, despite the prevalence of many of similar structural questions in Asian contexts, such a moment/emergence still eludes queer cinemas in other parts of the world. These subjectivities (of other localities) are continually shaped by the neoliberal co-option of queerness in mainstream and commercial film production values; and exhibition and distribution are caught within many nationalisms, racial borders, and linguistic regionalisms.

Retrospectively it seems impossible to think that one could ask after the question of “worth” of work by Andy Warhol, Kenneth Anger, Derek Jarman, Isaac Julien, Marlon Riggs, Lizzie Borden, Jenny Livingston, or Kimberley Peirce, let alone John Waters and Tilda Swinton, and not also understand that the impediments and inequalities they faced are similar and relevant to queer filmmakers from the global south. Rather, in addition to contending with social, cultural, and political repression, filmmakers such as Fan Popo, Debalina, He Xiaopei, Jayan Cherian, Selim Mourad, Cha Roque, Sungbin Byun, Güldem Durmaz, Sridhar Rangayan, Atikah Zainidi, Hyung-suk Lee, Kean Hian Lim – to name a miniscule few – also have to compete with racial and nationalist film consumption preferences and canons. This is without mentioning the suffocating flow of banal and privileged mainstream cultural production that seeks to profit off of LGBTQ+ representation as more diversity tokenism.

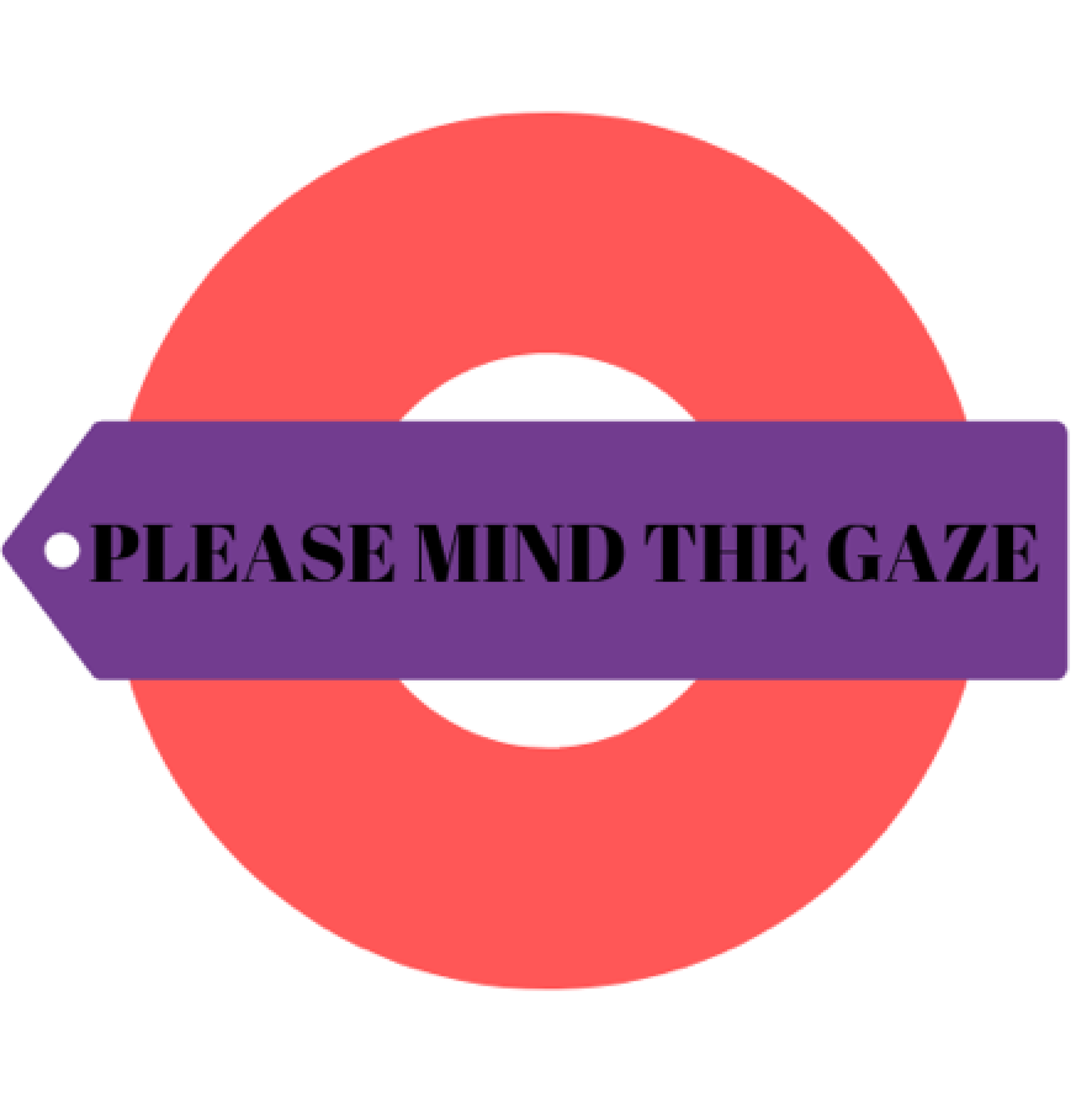

I argue that the question of worth be responded to through a queer curatorial praxis as a countering strategy: a postcolonial and queer decolonial politics which recognizes the impossibilities of the inequalities at play. I call this a “Homo Poco” kind of logic that only answers the question of “worth,” with the sign that says, “please mind the gaze” (see image 1; also see Lo 2018). This sign, I made the night before the 2018 film festival program was to go live, partly in anger over the many rejected visas, partly in frustration from the limited resources we had, and partly in response to the question of “worth” I was being asked about. The sign would not have been approved for use by the team at British Museum – I had to run everything past them. But on the first day of the festival, in an act of defiance, I loaded it into the film reel and allowed the sign to stand-in between films on the program where filmmakers’ talks had to be cancelled due to the structural conditions and coloniality of the UK Border.

Image 1: PNG of the sign inserted into the film reel where visa cancellations and visa restrictions impinged on the programme. This sign accompanied an announcement about visa restrictions and the UK border that attempted to make present the glaring absences of filmmakers and performers. This sign replicates the banal and commonplace sign on the London Underground in an effort to ask audiences to be constantly aware of the racist, nationalist, and majoritarian logics that might subconsciously work to interpellate their gaze.

Finally, this leads to the third step in a queer curatorial praxis: attempting the labor of negating the inequalities of access while also critically examining the geopolitics of location; the racial, classed, and gendered logic of borders; and the nationalist limitations that prevent greater south-south collaboration and solidarity. To rephrase Guneratne on a radical filmmaking practice – but in the context of film curation – I argue that a queer curation must also “underline its ideological rejection” of the “industrial modes” (Dissanayake and Guneratne 2004) which sustain the atomized and depoliticized consumption of queer film from the global south. Such curation needs to actively work to materially challenge the structural impediments which make depoliticized consumption all too convenient.

This, however, is a big ask, and perhaps a far too idealistic ask. In a time of rampant neoliberal modes of production and consumption (Duggan 2004; Harvey 2007; Rofel 2012), is the pursuit of such a politics pre-destined for failure?

Self-selecting Audiences and a Failed Mandate

The question of worth has also prompted an introspective reflection on the process of programming. In 2017, the films were screened on a Sunday after a two-day academic conference. This was a bad idea. What we had in 2016 was only possible because the audience was already there, attending the conference. In 2018, learning from that failure, the festival ran parallel to the conference and audiences could choose three parallel sessions as well as visit the “Queer” Asia Art Exhibition (and sign the protest letter to the Home Office). Together they made of “Queer” Asia 2018: BodiesXBorders a humming hotspot of queer activity (of all sorts).

However, in both 2017 and 2018, film viewership particularly was self-selecting based on race, gender, sexuality, and nationality. Each feature film tended to have a new audience barring the festival regulars. Programming had failed precisely because it allowed the perpetuation of area ghettos. The blame for this rests with the curation, as we picked submissions that were feature films and documentaries over the queer short films. Moreover, it is unlikely that audiences would sit through more than one feature film at a time.

Yet did part of this self-selection also reflect a cultural, nationalist, and racial bias? The process of curation came with a difficult learning curve that was – for me as a curator, practitioner, and researcher – as rewarding as it was steep. It required unlearning aesthetics informed by nationalist canons, class-based consumption patterns, and access to capital; aesthetics informed by consumption of mainstream and hegemonic film and video; by racial preferences underlying the national imaginary. It also meant understanding what contexts and what sort of self-funded budgets filmmakers are working with. Was this work of unlearning our own expectations about what is a queer film something an audience was interested in doing at all at a film festival?

What sticky affects (Ahmed 2005) are triggered in these processes of unlearning? As Ahmed explains, national communities are formed through affective identification/dis-identification from different types of strangers. She argues that “the nation is a concrete effect of how some bodies have moved towards and away from other bodies, a movement that works to create the very affect and effect of boundaries and borders” (2005, 108). This led to East Asian films being seen by mostly East Asian audiences, South Asian films by South Asian audiences and so on, to the point that, barring a few trans people, no one else attended events that centered trans experiences. Can queer curation foster meaningful south-south solidarities by encouraging audiences to do the work of building their capacity for “turning back or turning around” (2005, 109) towards racialized and other others? To embark on the hard work unlearning requires?

Having curated film programs for other festivals, often reporting to different festival directors, I received different mandates for film curation based on audience management. At times I have been told that audiences don’t want to see “something depressing” or been asked to find “happy affirming stories”; at other times my selections that included more home-made kind of film and video were rejected in favor of more “feel good” and “polished content” (what is this an effect off?). Often audiences’ mental health or tastes are cited as a reason for such curatorial direction. By contrast, my curation at “Queer” Asia has come to be a way to build solidarity by disorienting the uncritical consumption of mainstream and hegemonic representation of queer lives and struggles.

In practical terms this means allowing the film and video to function as a curated collection of narratives, images, stories, affective ties, struggles, and hardships that enrich our understanding of the many fronts on which LGBTQ+ people in the global south struggle. The curation shoulders the responsibility of navigating the specificities of the films and their production context, as well as the rationale for their juxtaposition. Curation’s role is to foster and build a grounded and action-oriented solidarity amongst audiences. In doing so it aims to cultivate that “hope of postcoloniality” (Ahmed 2005, 109) wherein audiences come to share community irrespective of our differences. Can this shared understanding serve to foster greater solidarity that transcends our national limitations and many constructed “preferences”? It also means decentering the barrage of images of whiteness, upper-class, and upper-caste-ness, of similar kinds of toned/fit bodies, of ableist notions around sexuality that shape and regulate our own desires, subjectivities, and imaginaries of sexual pleasures. Stuart Hall (1996; 2019) and Gloria Anzaldúa (2007), and their different but related articulations of learning born of straddling two or more cultures at the same time, are a guiding force in my pursuit of these questions; they help me reflect on the multiple and contrary ways in which subjecthood is constituted by the choices exercised in the name of racial preferences, nationalist limitations, and sexual and gendered desires.

Therefore, we thought through the self-selection enabled by my curation, and that of the team I was leading. To have programmed in a way that was susceptible to use within “area ghettos” is what I would qualify as something not quite-failed yet not-quite achieved. The fourth and most difficult step in building towards a queer curatorial praxis is critical reflection; it meant sitting with the emotions and asking, why – despite the praise and success we received – I felt saddled with a heavy sadness.

Rethinking Curation: The Queer Short Film and “Queer” Asia 2019-2020

I remember sitting with this sadness for months after, feeling let down but also confused. I was reassured when Jennifer Ung Loh – my close friend, co-organizer of “Queer” Asia, and curator – said they felt a similar way. It gave me reassurance to pause and reflect on the affect that drove the work we did and its causes. Our work, as with other identity-based festivals and queer curatorial work, is highly precarious (Loist 2011) while also being tokenized and deployed under diversity and inclusion sort of metrics in neoliberal institutions.10

I felt compelled to continue this work because it was necessary for my own survival within academia as a queer person of color from Delhi, and a first generation Ph.D. within my family. Additionally, the space we had created was unique and urgently needed within UK academia and cultural spaces. The uniqueness of our work also stemmed from our global south focus and the sustenance it afforded to others marginalized within both Area Studies and white queer/feminist spaces. The space is also organized in a way that is constantly reflective and foregrounds a non-hierarchical inclusivity, understanding, and compassion for the struggles of young scholars from global south and other marginalized contexts. To draw on Stuart Hall, it was an attempt to put into practice “a politics of living identity through difference” (2019, 78). Being attentive to the impossibilities of the global north borders is one part of that. Most of us already navigate the impossibilities of the UK Border very frequently with visa check-ins at police stations, impossible visa costs, and frustrating calculations on affording to travel home. Most of us are also accessing UK academia as queer people from the global south or from non-privileged and minoritized backgrounds within the UK. Therefore, despite having different teams each year with a few of us remaining common across all the years, we shared an understanding of the struggles people – artists, activists, academics, and filmmakers – face in the UK. Working closely with each other also helped us recognize and share our experiences in a way that enabled us to see past our national and racial constraints, our focus on academic specialties, and the other socio-cultural and financial constraints that inform our subjectivities. I continue to experience our commitment to this work and these solidarities as a shared navigation of our otherness and our queerness, even though at times these came with painful and irreconcilable moments. Where some such moments have led to new innovations, others have led to irreconcilable differences and departures.

One particularly difficult moment arose when two of the four of us – Ng How Wee, Allan Simpson, Aapurv Jain, and I – who started “Queer” Asia parted ways in 2018 because of the irreconcilable differences between approaches. However, this is not my story to tell. Rather, what I want to offer is my understanding of the structural questions that informed that impasse. It centers again on a fundamental question of access to the UK Border for a participant and a committee member, and the limited resources we had access to. On both sides of the difference – one advocating to support an Asian queer artist to participate at the 2018 conference and the second, a committee member based outside the UK and working to put together the 2018 conference, advocating for their own participation at the conference – there was a compelling case. To navigate this impasse, we allocated our limited funding to the artist and some of us developed a new funding proposal to enable the committee member, an activist working in development in the global south, to be able to fund their travel and expenses to the UK. What struck home, but also emphasized the scale of our curatorial failure, was the impossibility, arising from precarity, to see past their differences and work together in solidarity to propose a solution. More importantly, navigating this impasse also came from a recognition of the pressing constraints of the precarity that all of us were experiencing. What was central for me was understanding that this work in building towards a queer and feminist global south solidarity needs at its core a sustained culture of living-with and accepting differences, and a practice that recognizes the materiality of cultural work of this sort.

Coupled with my growing sense of sadness over the impossibilities of borders, resources, and area silos, this moment led to the realization that thus far curation had been unable to translate that ethos of a shared sense of solidarity and community sufficiently. This required a structural change in the way “Queer” Asia was organized.

The After-Affect of Queer Curation

I spent many months after the 2018 conference and festival taking stock of the impasse, the borders that frustrated our work, and acknowledging the many failures of curation. Jennifer and I made a difficult but important resolve to cancel the conference and replace it with a summer program to share and theorize the many complexities we had encountered. I also rethought the film festival, and along with a new small curatorial team, decided to adopt the queer short film as our tool to navigate the area ghettos and overcome some of the curatorial failures discussed above.

Our new call for submissions was widely successful, yet with multiple flaws: in comparison to the 2018 festival which received over eighty submissions, the 2019 festival received over thirteen hundred submissions from eighty-four different countries and a few marked “unspecified” under nationality. This came with its own problems. It required an extraordinary commitment of time and labor of care to watch all the films, to curate the program, and to also understand the context within which the films were working or coming from. For this latter purpose we asked for a submitter’s statement. Other questions we had to navigate included issues of language and translation, barriers in communication, and our and the filmmaker’s understanding of what queer meant, looked like, or felt like in the multiplicity of contexts. We also had many deep, exciting, and difficult conversations amongst the curatorial team about what is queerness, what felt like queerness, what might be queerness but we are unable to recognize it.11

The mandate that we worked with to inform our selection was rooted in an expansive understanding of queer. It included: practices and identities; sexual acts constructed contrary to diegetic norms; campaigns or protests; an understanding that none of these might be sufficient. Thus, we curated an extremely diverse set of sixty short films which we thematically programmed under broad collections. These collections were labelled “The Child,” “Inside Out/Outside In,” “Power Out!,” and “Feeling Bodies.” We also collaborated with CINEMQ Shanghai, an underground queer collective, who curated three programs.12 The festival program itself was separated from the rest of the “Queer” Asia events and spanned a whole month, three cities in the UK, and several institutions.

We provided visa letters and funds, where we could, to help filmmakers join in on the conversations at the festival. Where this was not possible, we switched to enabling the curatorial voice to elaborate how the program worked to navigate a shared or disparate understanding of queerness. This was a remarkable change in strategy as I felt the conversations once again were richer than the previous two years, that people stayed through whole programs – not everyone did, but it was good enough. I was able to once again enjoy the layers of nuance that came from an unexpected juxtaposition of texts and contexts – akin to what Gayatri Gopinath defines as queer curation (2018), of the newness of theorizing through film and video, and an embrace of the differences that were rooted in our shared sense of otherness.

2020: Queerness in Praxis in the Pandemic

The change in direction facilitated a series of affective engagements that allow for a negotiation of what a queer praxis might mean in the academy. It resulted in forging affective ties that manifested into beautiful new collaborations. These included the work being done in Berlin and Hamburg through a new team running the “Queer” Asia in our Germany chapter.13 Similar collaborations have been sites of rewarding queer praxis in the UK with the Queer Qāndi Film Festival in late 2020. It also resulted in new collaborations with Queer China UK that are underway.

The pandemic brought us to rethink the film festival planned for June-July 2020. However, cancelling and rethinking in solidarity are two different things. While the first centers and protects the self, the second shapes my queer curatorial praxis. It meant rethinking entirely what was doable to address, in some way, the inequality of the impact the pandemic was having on queer and trans people globally.

The praxis-based work and the affective ties nurtured over the years informed my curation of a short online-only program that accessed institutional funding to pay filmmakers screening fees. Drawing on their knowledge of struggling local communities, my curation sought to be responsible to the transnational communities the films focused on and used the screenings as a fundraising drive. Thus the 2020 film festival was called the COVID-19 Community Support Screenings.14 The film festival was able to fundraise for homeless queer and trans youth in London and Beijing, for elderly people in Al Rafah, for trans and intersex people in Chennai, Bangalore, and Manila. We hoped that the screenings and online events were also a way for queer people isolated from their support networks to find connections – nothing significant compared to what was really needed, and still is.

However, it made possible a praxis that understands redistribution as a necessary part of addressing the disparities that affect us. This is particularly an important point of learning from trying to organize within global north institutions that have benefited from, and continue to do so, from centuries of colonial extraction of knowledge, people, and resources (Cusicanqui 2012). A queer curation that does not shoulder this labor of care and solidarity but rather remains uncritically enmeshed within – and profits off – the same structures of power that replicate and rely on the dominance of global north institutions and power structures, is, to varying degrees, a complicit curation; as is a queer curation that seeks to tokenize and profit-off of LGBTQ+ lives and struggles within the global south if not supported by a material labor of care towards the communities it works with.

Concluding Notes

I return to my opening question on what makes a film festival queer. Responding to this question by rephrasing Hall (2019, 79) to suggest that just because a film festival is run by and for people whose sexual or gender identity is aligned with the LGBTQ+ spectrum does not necessarily equate to a queer praxis. Similarly, it would hold, that just because a film is made by people who identify as LGBTQ+, that does not automatically make it a queer film. Rather it is—as Teshome Gabriel (1982) emphasizes and as Schoonover and Galt (2016) show—in the praxis, curation, and the interaction with audiences that the question of queerness lies.

Queer has, like decoloniality, become the buzzword that attracts corporates precisely because it can circulate as new currency in the neoliberal economy (Duggan 2004; Berlant and Warner 1998) without the disruptive praxis (Lewis 2016) that it also demands. Queer curation, as I have attempted to show, needs to be a conscious disruptive and redistributive praxis that is tied to unsettling extractive practices of consumption; requisitioning institutional resources for redistributive work (Shahani, 2020); building towards a shared subjectivity that challenges the hegemony of borders, or nationalisms, regionalisms; and the metonymy that replicates the “us” versus “them” logics of exclusion. It is an urgent need of the hour to wrestle queerness back from those who deploy it for personal gain and profit. This is a direction for queerness that Judith Butler, amongst others, long foresaw as a “site of collective contestation … redeployed, twisted, queered from a prior usage and in the direction of urgent and expanding political purposes” (1993, 19). It is when curation takes on the material labor of care and decolonization (see Sayegh and Allouche, 2020) that it shapes an orientation towards what can be a powerful and radical queerness.

- 1. “Queer” Asia began as a small student organised conference in 2016 at SOAS, University of London. It currently operates as a loose network of early career academics, activists, and artists in London and Berlin. The latest iteration of the “Queer” Asia Film Festival, titled “Imagining Queer Bandung” is being hosted in Berlin by the “Queer” Asia in Germany team and grew out of the first four-day “Queer” Asia Summer Programme hosted in London in 2019. More details on the work of “Queer” Asia and the concepts can be found in our book “Queer” Asia: Decolonising and Reimagining Sexuality and Gender (Luther and Ung Loh, 2019) and on the “Queer” Asia website. The film festivals were an off shoot of the “Queer” Asia conferences and began in 2017.

- 2. I define a South-South collaboration as a praxis that looks towards anti-racists, anti-capitalist, queer, and decolonial projects globally in building movements and challenging oppressive power structures. I draw on the work of The Santa Cruz Feminist of Color Collective (2014), Kuan-Hsing Chen’s text Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization (2010), and the Inter-Asia Cultural Studies project building on the work of Stuart Hall at Birmingham University (Chen, 2017) to contextualise my understanding of South-South collaboration.

- 3. Jack Halberstam (2011) is helpful in unthinking the negative connotations of failure. Instead imagining it as an epistemological framework that works to locate alternative ways of being and directing the negative affects of failure to challenge curators and audiences at film festivals alike.

- 4. A UK tourist visa costs GBP 350, not necessarily the appropriate visa for a conference but a cheaper and easier option. This is a significant amount in other currencies.

- 5. The REF is the research excellent framework and the TEF is the teaching excellence framework used within the UK context to determine promotions, hiring, and academic value, see for instance Sabiha Allouche’s response in the launch of the Queer Feminisms issue of the Kohl Journal (Ghiwa Sayegh, Sabiha Allouche, Sarona Abuaker, Aya El Sharkawy, Ahmed Ibrahim, Nour Almazidi, Sara Ahmed, 2021).

- 6. A digital copy of the letter that we drafted and that was installed in the exhibition is available here - https://docs.google.com/document/d/1vS94UkpYZxcdc4i5GvSdX3_PW79Ky9N5IQs4g1mL2QA/edit?usp=sharing.

- 7. See the important work by the network of BAME scholar-practitioners at Museum Detox (Wajid and Minott 2019). Similarly see queer and trans work in and against the heteronormativity of museums (Scott 2018; Bosold, Scott, and Chantraine 2020). See also work by Leila Aboulela, particularly her short story “The Museum” (1999).

- 8. Perhaps this is also a failing in the eyes of decolonial practitioners, but it merits pause to reflect: outside of critical circles, does association with the British Museum as an exhibition venue carry socio-cultural weight?

- 9. On the use of black as a political term in the British context see also Amos and Parmar (1984).

- 10. This requires a lot more unpacking that I do not have the space to go into here, but it is important to situate this work in relation to Sara Ahmed’s work (see 2012).

- 11. We also keep having similar conversations on what submission qualifies as “Asia.”

- 12. See more about their work here: https://www.cinemq.com/

- 13. See the 2021 instalment of the “Queer” Asia Film Festival called “Imagining Queer Bandung” here: https://queerasia.com/qa21iqb/

- 14. See the 2020 digital-only festival programme here: https://queerasia.com/2020ccs/

Aboulela, Leila. 1999. “The Museum.” In Opening Spaces: An Anthology of Contemporary African Women’s Writing, edited by Yvonne Vera. Heinemann.

Ahmed, Sara. 2005. “The Skin of the Community: Affect and Boundary Formation.” In Revolt, Affect, Collectivity: The Unstable Boundaries of Kristeva’s Polis, edited by Tina Chanter and Ewa Plonowska Ziarek. Ithaca: State University of New York Press.

Ahmed, Sara. 2012. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Duke University Press.

Althusser, Louis. 1971. Lenin and Philosophy, and Other Essays. London: New Left Books.

Amos, Valerie, and Pratibha Parmar. 1984. “Challenging Imperial Feminism.” Feminist Review 17 (1): 3–19. doi.org/10.1057/fr.1984.18.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 2007. Borderlands: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books.

Arondekar, Anjali, and Geeta Patel. 2016. “Area Impossible Notes toward an Introduction.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 22 (2): 151–71. doi.org/10.1215/10642684-3428687.

Bao, Hongwei. 2019. “The ‘Queer Generation’: Queer Community Documentary in Contemporary China.” Transnational Screens 10 (3): 201–16. doi.org/10.1080/25785273.2019.1662197.

Berlant, Lauren, and Michael Warner. 1998. “Sex in Public.” Critical Inquiry 24 (2): 547–66. jstor.org/stable/1344178.

Bosold, Birgit, E. J. Scott, and Renaud Chantraine. 2020. “Queer Tactics, Handwritten Stories: Disrupting the Field of Museum Practices.” Museum International 72 (3–4): 212–25. doi.org/10.1080/13500775.2020.1873525.

Butler, Judith. 1993. “Critically Queer.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 1 (1): 17–32. doi.org/10.1215/10642684-1-1-17.

Chen, Kuan-Hsing. 2010. Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Duke University Press. jstor.org/stable/j.ctv11smwwj.

Cohen, Lawrence. 2005. “The Kothi Wars: AIDS Cosmopolitanism and the Morality of Classification.” In Sex in Development: Science, Sexuality, and Morality in Global Perspective, edited by Vincanne Adams and Stacy L. Pigg. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera. 2012. “Ch’ixinakax Utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization.” South Atlantic Quarterly 111 (1): 95–109. doi.org/10.1215/00382876-1472612.

Dasgupta, Rohit K. 2017. Digital Queer Cultures in India: Politics, Intimacies and Belonging. Taylor & Francis.

Deklerck, Stijn. 2017. “Bolstering Queer Desires, Reaching Activist Goals: Practicing Queer Activist Documentary Filmmaking in Mainland China.” Studies in Documentary Film 11 (3): 232–47. doi.org/10.1080/17503280.2017.1335564.

Diaz, Robert G. 2012. “Queer Love and Urban Intimacies in Martial Law Manila.” Edited by Rolando B Tolentino. Plaridel: A Philippine Journal of Communication, Media and Society 9 (2): 1–19.

Dissanayake, Wimal, and Anthony Guneratne. 2004. Rethinking Third Cinema. Routledge.

Dovey, Lindiwe. 2015. Curating Africa in the Age of Film Festivals. Framing Film Festivals. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Duggan, Lisa. 2004. The Twilight of Equality: Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy. Reprint edition. Boston: Beacon Press.

Dwyer, Rachel. 2011. “Zara Hatke (Somewhat Different): The New Middle Classes and the Changing Forms of Hindi Cinema.” In Being Middle-Class in India: A Way of Life, edited by Henrike Donner, 200–224. Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series 53. London; New York: Routledge.

Fanon, Frantz. 1967. The Wretched of the Earth. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin.

Gabriel, Teshome H. 1979. “Third Cinema in Third World: The Dynamics of Style and Ideology.” PhD diss., University of California Los Angeles.

Gabriel, Teshome H. 1982. Third Cinema in the Third World: The Aesthetics of Liberation. Studies in Cinema, no. 21. Ann Arbor; Epping: UMI Research: Bowker.

Ganti, Tejaswini. 2012. Producing Bollywood: Inside the Contemporary Hindi Film Industry. Durham: Duke University Press.

Gopinath, Gayatri. 2018. Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora. Duke University Press.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1978. Antonio Gramsci: Selections from Political Writings (1921-1926); with Additional Texts by Other Italian Communist Leaders. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Halberstam, Jack. 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. North Carolina, US: Duke University Press.

Hagedorn, Jessica. 2013. Dogeaters. Open Road Media.

Hall, Stuart. 1996. Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. Comedia. London: Routledge.

Hall, Stuart. 2019. “Old and New Identities, Ethnicities.” In Essential Essays, Volume 2: Identity and Diaspora, edited by David Morley. Duke University Press.

Hallas, Roger. 2003. “AIDS and Gay Cinephilia.” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 18 (1 (52)): 85–127. doi.org/10.1215/02705346-18-1_52-85.

Harvey, D. 2007. A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford and New York: xford University Press.

Iordanova, Dina. 2015. “The Film Festival as an Industry Node.” Media Industries Journal 1 (3). doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0001.302.

Iordanova, Dina, and Ragan Rhyne, eds. 2009. The Festival Circuit. Film Festival Yearbook 1. St. Andrews, Scotland: St. Andrews Film Studies in collaboration with College Gate Press.

Jackson, Peter A., Fran Martin, and Mark McLelland. 2005. “Re-Placing Queer Studies: Reflections on the Queer Matters Conference (King’s College, London, May 2004).” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6 (2). doi.org/10.1080/14649370500066035.

Jacobs, Katrien. 2020. “Smouldering Pornographies on the Chinese Internet.” Porn Studies 7 (3): 337–45. doi.org/10.1080/23268743.2020.1776151.

Keshavarz, Maryam. 2011. Circumstance. Drama. Marakesh Films, A Space Between, Bago Pictures.

Khaleeli, Homa. 2012. “Maryam Keshavarz: ‘In Iran, Anything Illegal Becomes Politically Subversive.’” The Guardian, August 23.

Kredell, Brendan, Skadi Loist, and Marijke de Valck, eds. 2016. Film Festivals: History, Theory, Method, Practice. London; New York: Routledge.

Lewis, Holly. 2016. The Politics of Everybody: Feminism, Queer Theory and Marxism at the Intersection. London: Zed Books.

Littin, Miguel, Gary Crowdus, Irwin Silber, and Susan Hertelendy Rudge. 1971. “FILM IN CHILE: An Interview with Miguel Littin.” Cinéaste 4 (4): 4–11. jstor.org/stable/43868788.

Lo, Tim. 2018. “How a Queer Asian Saw ‘Queer’ Asia 2018.” Rife Magazine (blog). June 28. rifemagazine.co.uk/2018/06/how-a-queer-asian-saw-queer-asia-2018/.

Loist, Skadi. 2011. “Precarious Cultural Work: About the Organization of (Queer) Film Festivals.” Screen 52 (2): 268–73. doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjr016.

Luther, J. Daniel, and Jennifer Ung Loh, eds. 2019. “Queer” Asia: Decolonising and Reimagining Sexuality and Gender. London: Zed Books.

Martin, Fran, Peter A. Jackson, Mark McLelland, and Audrey Yue, eds. 2008. AsiaPacifiQueer: Rethinking Genders and Sexualities. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Murtagh, Ben. 2019. “Reimagining HIV in Indonesian Online Media: A Discussion of Two Recent Indonesian Webseries.” In “Queer” Asia: Decolonising and Reimagining Sexuality and Gender, edited by J. Daniel Luther and Jennifer Ung Loh, 45–64. London: Zed Books.

Perry, G. M., Patrick McGilligan, and Ousmane Sembene. 1973. “Ousmane Sembene: An Interview.” Film Quarterly 26 (3): 36–42. doi.org/10.2307/1211343.

Popo, Fan, and Bao Hongwei. 2019. “‘Love Your Films and Love Your Life’: An Interview with Fan Popo.” Positions: Asia Critique 27 (4): 799–809. doi.org/10.1215/10679847-7726994.

Rajadhyaksha, Ashish. 1985. “The Tenth International Film Festival of India: Scattered Reflections around an Event.” Screen 26 (3–4): 147–51. doi.org/10.1093/screen/26.3-4.147.

Rastegar, Roya. 2012. “Difference, Aesthetics and the Curatorial Crisis of Film Festivals.” Screen 53 (3): 310–17. doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjs022.

Rastegar, Roya. 2016. “Seeing Differently: The Curatorial Potential of Film Festival Programming.” In Film Festivals: History, Theory, Method, Practice, edited by Brendan Kredell, Skadi Loist, and Marijke de Valck. London; New York: Routledge.

Rhyne, Ragan. 2006. “The Global Economy of Gay and Lesbian Film Festivals.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 12 (4): 617–19. doi.org/10.1215/10642684-12-4-617.

Rich, B. Ruby. 2000. “Queer and Present Danger: After New Queer Cinema | Sight & Sound.” Sight & Sound, March. bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/features/queer-present-danger-b-ruby-rich.

Rich, B. Ruby. 2013. “The New Queer Cinema: Director’s Cut.” In New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut. Durham: Duke University Press.

Rocha, Glauber, Gary Crowdus, Wm. Starr, Ruth McCormick, and Susan Hertelendy. 1970. “CINEMA NOVO VS. CULTURAL COLONIALISM: An Interview with Glauber Rocha.” Cinéaste 4 (1): 2–9. jstor.org/stable/43868804.

Rocha, Glauber, Ismail Xavier, Stephanie Dennison, and Charlotte Smith. 2019. On Cinema. Tauris World Cinema Series. London: I.B. Tauris.

Rofel, L. 2012. "Queer positions, Queering Asian Studies." Positions: Asia Critique 20 (1): 183 - 193.

Sanjines, Jorge. 1970. “Cinema and Revolution.” Cinéaste 4 (3): 13–14. jstor.org/stable/41685720.

Sayegh, Ghiwa, Sabiha Allouche, Sarona Abuaker, Aya El Sharkaway, Ahmed Ibrahim, Nour Almazidi, and Sara Ahmed. 2021. “An Archive of Queer Feminisms with Sara Ahmed.” Kohl: A Journal for Body and Gender Research 6 (3): 424–40. kohljournal.press/Archive-Queer-Feminisms-Sara-Ahmed.

Sayegh, Ghiwa, Sabiha Allouche. 2020. "Circling: a Methodology." Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research 6 (3): 239–242. kohljournal.press/circling-methodology. doi: 10.36583/2020060301.

Schoonover, Karl, and Rosalind Galt. 2016. Queer Cinema in the World. Durham: Duke University Press.

Scott, E. J. 2018. “The Museum of Transology: Protesting the Erasure of Transcestry.” In Prejudice and Pride: LGBTQ Heritage and Its Contemporary Implications, edited by Richard Sandell, Rachael Lennon, and Matt Smith, 18–21. Leicester: Research Centre for Museums and Galleries, School of Museum Studies, U. of Leicester.

Seth, Analita. 2018. “All about India’s First Silent LGBTQ Short Film, Sisak.” Filmfare.Com, September 6, 2018. filmfare.com/news/bollywood/all-about-indias-first-silent-lgbtq-short-film-sisak-30189.html.

Shahani, Parmesh. 2020. Queeristan: LGBTQ Inclusion in the Indian Workplace. Westland.

Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. 2013. Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media. Sightlines. Taylor and Francis. doi.org/10.4324/9781315002873.

Simpson, Allan. 2017. “What Do Queers Want? QA17 Summary.” “Queer” Asia (blog). August 30. queerasia.com/2017/08/30/what-do-queers-want-qa17-summary/.

Singh, Julietta. 2018. No Archive Will Restore You. punctum books.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 1988. In Other Worlds: Essays in Cultural Politics. New York; London: Routledge.

Valck, Marijke de. 2007. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia. Amsterdam University Press. library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/35273.

Wajid, Sara, and Rachael Minott. 2019. “Detoxing and Decolonising Museums.” In Museum Activism, edited by Robert R. Janes and Richard Sandell. Routledge.