War Journal

war_journal.jpg

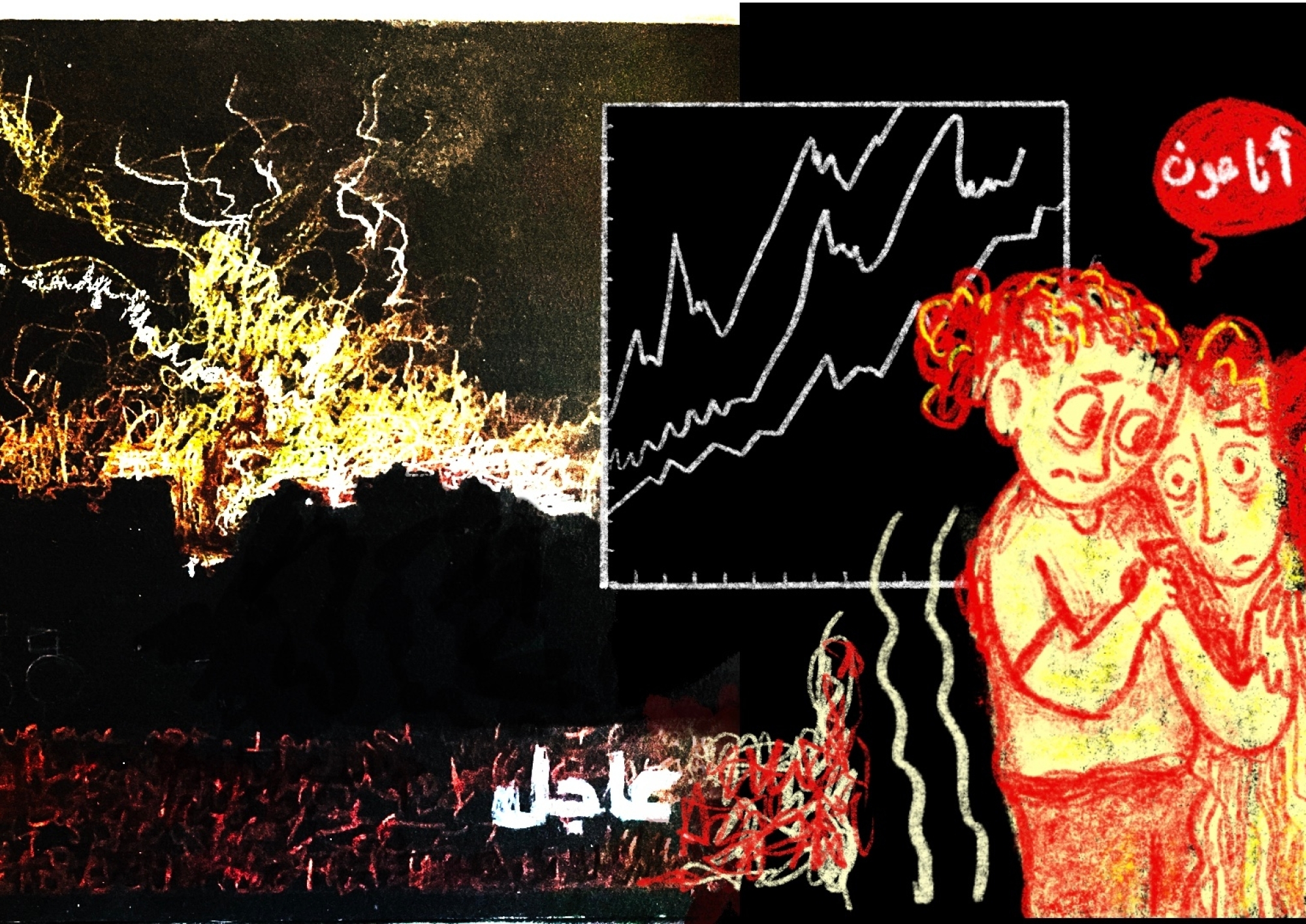

Myra El Mir

The buzzing sound of an airplane, and mom embraces us with her warm soft touch, as if it’s our last breath. A bomb falls, the ground shakes, and I hide behind my mother’s back – an armor. She reassures us – “everything’s going to be okay,” assures us that we are going to survive this. We light our candles, following the shadows in front of us, and head to the nearest shelter amidst all of the chaos, the echo of the bombs haunting us. I hang on a rope between reality and dreams. I am 6 years old.

I didn’t quite understand what was happening back then; our life wasn’t stable. I was used to the idea of moving in and out of places, and grandma’s small rented house in the Bourj Al Chemali refugee camp was not a strange place to be at. We had left our apartment in Sour because it was too dangerous: in 2006, the Israelis were bombing the city and taking over villages. In Sour, people had nowhere to go; they stayed at the beach because it was the safest spot they could find in the vicinity. They spent days and nights with little food and barely any resources, not knowing what was coming next.

***

It was only until the 2024 war that I fully comprehended how capitalism grabs us by the neck and slowly kills our spirit. Like everyone else, my family and I were uprooted from Jnoub (the South) and its golden, sandy beaches. We ended up in a small village in Akkar called Bebnine. The sky in Sour is veiled with a soft blue haze; in Bebnine, it lays down its shutters, revealing nothing but a grey hue that breaks into the shadows of buildings, before laying timidly over the city. Our entire extended family was crammed in a single house so we could afford to survive with the outrageous increase in expenses and rents. I was working remotely and had to make the best out of it for fear of getting fired – I was the only family member that still had a job.

No one was comfortable. Every day, a new fight would break out, and the stress was dreadful. One early morning, amidst the work and the fights, I had a breakdown. I couldn’t ask for time off work because I had barely started my shift and was on a tight deadline. Tears were streaming down my face. I didn’t know what to do, so I just continued working amidst the tears and the crushing noises that surrounded me.

It dawned on me then that I am literally chained by capitalism. I am nothing but a machine trying to finish work tasks on time in a country where I am barely alive. It is all a lie: what does it mean to get a good job? To let hierarchy draw the limits of who we are based on our salary, status, and background? What’s next? What am I supposed to do?

***

I don’t know where to start. I had moved out to Beirut a few months before, and I didn’t witness firsthand, like my family did, the horror of the pagers ambush. They were able to see all the bombing from Sour, with its proximity to the border with Palestine.

Once the strikes got too close, the war had officially started and my family decided to leave. They got stuck in traffic for a whole day, with as many memories that they could possibly fit in their bags, and left not knowing what was going to happen next.

In the meantime, I was in Mar Elias, and the owner of the apartment I was renting decided he wanted it back. We negotiated and pleaded, and he finally let us stay on the condition that we couldn’t host anyone (aka displaced people) in it. He ended up kicking us out anyway and renovated it, and till this day no one lives in it.

A friend of mine was hosted by her employers in a monastery in Monot. Since there were barely any reasonably-priced apartments for rental, I went to stay with her. The monastery was filled with rooms, just like a motel. Every three floors had a kitchen. There was a laundry room on the roof and the view was impeccable from up there.

At the monastery, we were three friends. Faf, Hilda, and I bonded so much during the war; we unpacked a lot of shit that we’d have never unraveled at any other time. We cried, we laughed, we held each other. We’d volunteer at the nearby church, where migrant domestic workers were staying, providing as much help as we possibly could.

Faf had her own definition of things and defied logic by all means. She was a very picky eater: she wouldn’t eat garlic or onions and wanted her meat cooked in a very specific way. I asked her once: “What about tabouli though? How can you eat it without onions?” She responded: “Green onions aren’t onions.” She didn’t consider Saida or Nabatieh a part of Jnoub. In her opinion, Jnoub began at Al-Qasimiyeh checkpoint.

We got caught up in the daily routine of war. We’d go to work, and once we’d come back, we’d head out to the common kitchen and plan lunch. We’d make sure that the food suited everyone. Some days, we’d just order from Chicken Way. Once we were sat on the square-shaped table over a meal, we’d catch up on everything that had happened at work and vent. Ironically, war had organized our lives amidst the chaos.

At night, we’d gather for our second cup of coffee of the day. We’d have it while fighting over a board game, cheating even, in order to win. The tension would rise and we’d stop halfway most of the time because we couldn’t handle it.

On calmer days, we’d have reading nights. We’d sit together and each one of us would read a book and discuss anything they might’ve found interesting afterwards.

***

I took a break from work. I wanted to make sense out of everything that was happening around me. On week-ends, I visited my family in Akkar. It would take me around three to four hours to get there. My sisters claimed that I lived in la-la land: I wasn’t with them during the bombing in Sour. And I wasn’t with them when they got stuck in traffic for a whole day until they reached Beirut. And yet, every day, I could hear all the bombs that fell on Beirut, and the amount of stress that we were all under was unimaginable.

On the 28th of October 2024, Zionists warned of imminent strikes to an area of Sour that included our home. I was working, but a friend called me on the spot and told me to check the news. His voice was shaking in fear; his parents had refused to leave their house and were still in Sour. We were literally counting the seconds down, blood running cold in our veins. We breathed every now and then, only when we remembered that we had to. The Zionists started firing rockets all over the city. On live TV, we saw buildings crumble to the ground; only dust and fog were left in their stead. Wired to always expect the worst, we imagined our goodbyes to a home we’d never go back to again. After a couple of hours, we checked in with the people who were still in Sour. My friend’s parents had survived, but his mother had injured her leg while escaping towards the beach. As for our building, it was still standing, but the one right next to it had collapsed.

***

When we heard the news of a ceasefire, we didn’t believe it at first. Would that mean we could actually head back? Would that mean that we could walk on boiling sand, that I would see the crowded beach of Sour again? Run the same path every morning and watch the sun rise, unraveling the sea before me?

On the last night before the ceasefire, I wanted to sleep the wait in, but I woke up every now and then to the sound of bombings targeting Beirut and its suburbs. Then Hilda, who hadn’t slept all night, barged into my room to inform me that strikes were going to hit our area. She was panicking and freaking out, and I was barely thinking straight from the lack of sleep. She suggested we take shelter in the church next to us. I held her close and said, “I don’t mind if it makes you feel safer. I’m by your side and hopefully nothing will happen.” She calmed down a bit. I told her that we were about to hear very loud sounds, but I assured her that I was there for her.

The bomb was very close, but nothing happened to us that night. We spent what was left of it together. From the rooftop, bombs lit the sky like exploding planets. We became so numb that we’d check where the next missile was set to fall on the map and point at it from where we were standing. Was it fucked up? Maybe. But nothing that was happening was logical. Time had died, and we were left with our aggressors’ concept of what it is: bombs, destruction, death, helpless cries of children and parents, psychological games, and nothing but horror.

Once the sun had fallen upon us, we were greeted by a new day. The ceasefire had officially started and the silence was deafening. A new terror settled – that of the unknown. Faf decided to go back to her home in Dahieh. She rushed into her car and I took the passenger seat while Hilda sat in the back. Faf played the song “Rajieen”1 on repeat until we arrived.

“مفتاح البيت بقلبي وانا راجع بإيدي ولدي”

(The key to my home remains in my heart and I'm returning with my children in my hands)

The air was thick. The streets were packed with cars and people and rubble. Seeing all the collapsed buildings on screen was one thing, and seeing them in real life was something else. Men were foolishly shooting in the air to celebrate the end of the war, in “victory.” Once we reached Faf’s house, she stepped out of the car and gazed at the building’s balcony with amazement, her eyes filling with tears. She pointed at it, saying: “That’s it, that’s it! It’s still here.” The building was surrounded by nothing but rubble and destruction. She ran inside, racing up the stairs. Once she reached her front door, she emptied her pockets for the keys but couldn’t find them.

She had forgotten the keys of her home.

***

It’s bewildering how our minds function. Our memories connect everything together like a road map, triggering every nerve. That’s exactly how our spatial cognitive memory works. I see the memories of the war every time I step into Dahieh, every time I see the people I spent the war with, in every corner that we stayed at and lived in. I keep asking myself, has the war actually ended? Is this it? Death is everywhere around us, and it is inevitable. Since the ceasefire, we have been walking on eggshells, watching the news constantly, expecting bombs anywhere, at any second. What is even a ceasefire at this point? We are labeling things into boxes, and giving the power to the colonizers to claim that the war is over. We are paralyzed by the language they use to define things on their own terms – that same language that the media abuses of. The Zionists could at any moment declare the ceasefire over, just like they are doing in Palestine, and we’ll be helpless. We aren’t prepared for this.

Time froze. The places that used to be are no longer. Yet has anything changed? The sea looms over the city with its depth, humidity takes over our breaths, and the sun embraces us with its presence. I’m back to Sour now. Time has shown us that nothing is fixed, nothing remains the same. We have run out of time – we’ve been robbed from that luxury. Now there is only waiting, even if we wait differently. As human beings we keep unraveling those layers that lay underneath each memory to transform them, and ourselves, into something new. We collide like passing clouds, craving the touch of one another, smothering our bodies together, bothered and unbothered with the world.