Reflections on Lebanon’s Civil Movement in the Midst of the War on Gaza

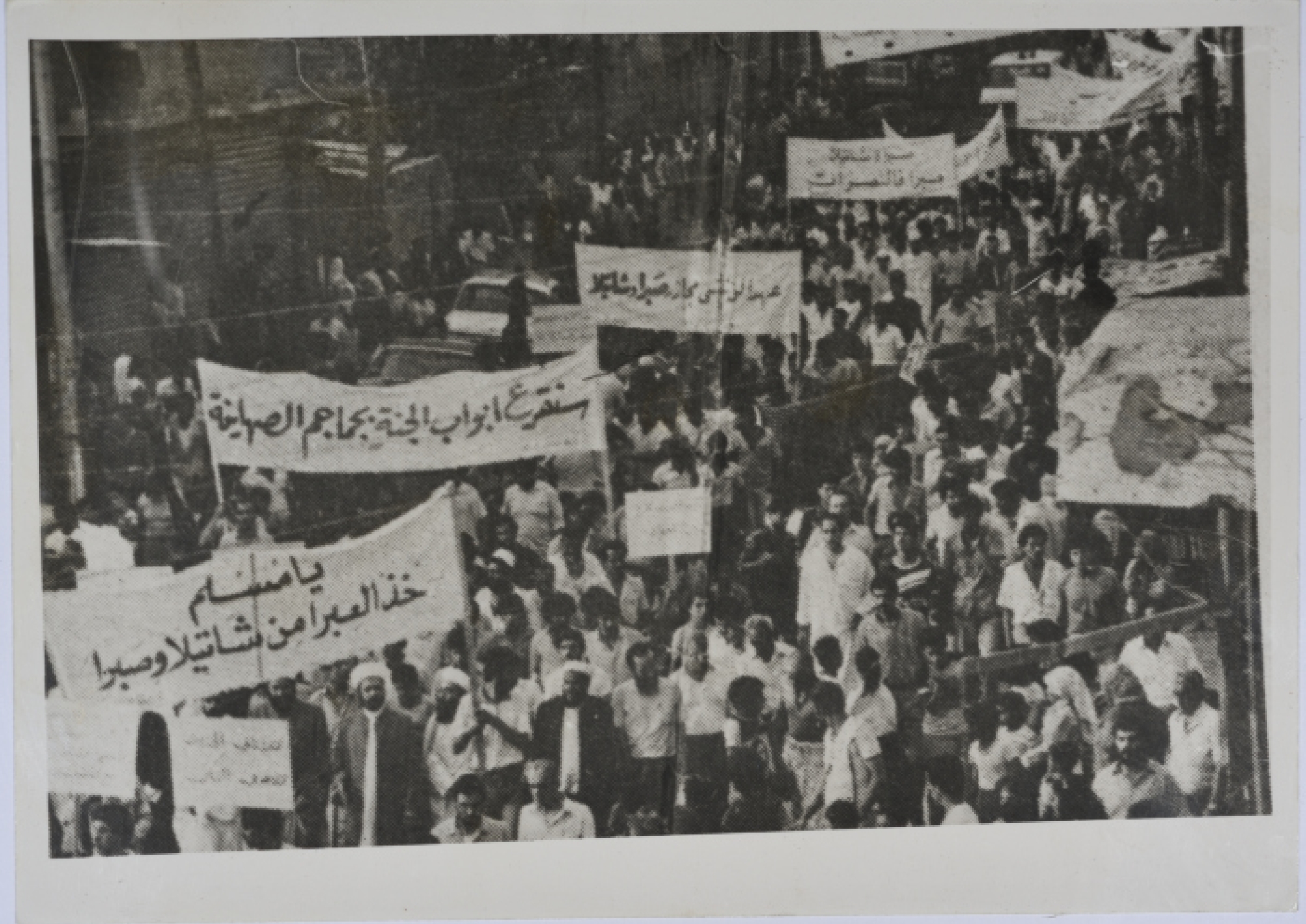

a_demonstration_against_the_sabra_and_shatila_massacre_1982.jpg

A Demonstration against the Sabra and Shatila Massacre, 1982

*This article was written before the escalation of the Israeli assault and the expansion of the war to Lebanon, which calls for a reflection on the Lebanese context leading to this moment.

As of October 2023, the “Al-Aqsa Flood” operation and the subsequent Israeli assault on Palestinians in Gaza have starkly illuminated the complexities of Lebanese identity and the profound divisions within Lebanon’s socio-political landscape. While large-scale protests against the Israeli attacks and in solidarity with Gaza and Palestine erupted around the globe, Lebanon witnessed only modest gatherings. This was particularly striking given Lebanon’s military involvement in the conflict since October 8, 2023, especially in the southern regions which have faced relentless Israeli strikes. The Lebanese regime permits some degree of protest, and Lebanon has a rich history of popular mobilizations – along with a significant historical connection between certain Lebanese communities and the Palestinian cause. Yet, demonstrations in support of Gaza or against the violence have remained limited. This lack of response has significantly fallen short of the expectations for action during this critical historical moment.

The continuation of life as near-usual in the Lebanese regions untouched by bombardments fosters a collective sense of estrangement. Keeping in mind that civil resistance is as vital as armed struggle, this article seeks to explore various aspects of public mobilization within Lebanon’s socio-political context, including conditions in Palestinian refugee camps. The primary focus is on popular protests in response to the ongoing war in Gaza, set against the backdrop of Israel’s persistent threats to escalate aggression in Lebanon.

Pre October 7th: Palestine and Lebanese History

Despite the deep historical ties linking Lebanon to Palestine, World War II simultaneously created the conditions for Lebanon’s independence1 and paved the way for the Palestinian Nakba by the Western-backed Zionist project.2 Under a governing system that sought to detach Lebanese identity from its Arabness and its surroundings, the Lebanese state portrayed Lebanon as “exceptional” and disconnected from regional contexts and crises, and solidified its relations with the West. This alignment resulted in a deeply divided society, split into two competing blocs: one comprised of social forces committed to strengthening economic, political, and cultural ties with Western nations, and another oriented, both historically and traditionally, toward the East.3

The 1947 partition of Palestine ignited a wave of strikes, demonstrations, and sit-ins throughout Lebanon, and the issue quickly became a focal point of political, national, and pan-Arab concern. This period was followed by the Nakba and the resulting mass displacement, fueling widespread street protests that called on Arab armies to intervene in the war on Palestine.4 The 1960s witnessed a surge of student and labor strikes condemning worsening economic conditions and the exploitation of the working class. These movements also advocated for mobilization and armament to defend Palestine and counter Israeli incursions into Lebanon. A 1969 article titled “A Round (and Fully Closed) Table” in Al-Hadaf examined the tensions between the ruling elite’s interests and the “everyday struggles and aspirations of the Lebanese masses,” noting that “the ordinary citizen in the South demands a rifle.”5

Years later, during the presidency of Charles Helou, Lebanese political forces – including the president and right-wing parties – advocated for building a modern state and society, preserving Lebanon’s independence and sovereignty, and avoiding involvement in regional conflicts. Fascist groups participated in suppressing student protests and attacking Palestinian and Lebanese revolutionary forces, as popular support for the Palestinian resistance grew, both materially and morally. Meanwhile, Lebanon’s national movement raised the slogan “Support the Fedayeen (guerilla) movement.”6

The 1960s in Lebanon were characterized by a systematic repression of Palestinians, with strict limitations on their freedom of movement and bans on basic activities such as listening to the radio, reading newspapers, and gathering publicly. Palestinians were also prohibited from moving between camps without permits, which were almost impossible to obtain. Subjected to daily harassment, extortion, arbitrary arrests, and torture, the Palestinians lived under constant surveillance by the police and the military intelligence agency, known as the “Second Bureau.” These oppressive conditions led to a spontaneous uprising within the camps in 1969:7 refugees expelled the “Second Bureau” and created the conditions for the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) to launch armed resistance operations from Lebanese territory. In this context, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon coalesced into a popular movement alongside the Lebanese National Movement (LNM), positioning Lebanon as a central stronghold for Palestinian resistance. Opposing forces, particularly Israel, exploited sectarian tensions to destabilize the alliance, ultimately contributing to the eruption of the Lebanese Civil War, during which three Palestinian camps were razed to the ground.8 As noted by Salah Khalaf, the threat transcended local dynamics, involving international actors as well, with “weapons secretly flowing into Christian militias.”9

The Civil War represented a significant loss for Palestinians in Lebanon, both politically and socially. However, it also saw a strong alliance between Lebanese and Palestinian resistance fighters, who faced attacks from Christian militias and Israel: “The Lebanese and Palestinian masses, as well as the fighters, expressed their feelings and thoughts by writing on the walls, which became filled with slogans reflecting their gratitude to the Lebanese people for supporting the revolution and their desire to continue the struggle together.”10

Following the conclusion of the Civil War, Lebanon witnessed a resurgence of street protests. The Hariri era was characterized by a focus on reconstruction and neoliberal urban governance. As a result, numerous strikes emerged in opposition to the privatization initiatives that had detrimental effects on the local economy. In September 1993, in reaction to the signing of the Oslo Agreement between the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Israeli government, a peaceful demonstration occurred in Ghobeiry, near the old airport bridge. Protesters vocalized their dissent against the Zionist state, but the gathering tragically culminated in a massacre perpetrated by the Lebanese army, resulting in nine martyrs and dozens injured.11

Hezbollah’s power grew significantly during and after the Civil War. While the organization advocated for the integration of Lebanon’s military efforts with the Palestinian cause, the war ultimately devastated the political presence of Palestinians in Lebanon, which aligned with Israel’s primary objective: “As confrontations persisted, it became increasingly clear that there was a strategic, long-term plan designed to eradicate Palestinian resistance and suppress the Palestinian civilian presence.”12 Over the years, the mechanisms of Palestinian resistance in Lebanon were systematically dismantled, coinciding with the decline of leftist parties and their retreat from the political arena, which in turn weakened their armed struggle against Israeli occupation in southern Lebanon.

Before and after the Civil War, Lebanese streets witnessed popular movements at various political junctures, as well as demands from trade unions. Trade unionists occasionally turned to the streets, much like party supporters at different stages of political change within the Lebanese landscape.

Following 2011, new political forces began to emerge outside of traditional parties, driven by the growth of civil society organisations. This led to a series of demonstrations in solidarity with the Arab Spring, culminating in the “You Stink” movement in 2015 and the October 17 uprising in 2019. While Lebanon had long been a space for the formation of political parties, the nature of political activism began to shift. Independent groups, predominantly characterised by neoliberal rights-based activism, emerged from civil society organisations that maintained connections with foreign embassies and received funding from them. As these organisations attracted some members of the left, the concepts of solidarity and activism replaced the focus on the struggle, leading to a fragmentation of political action into sub-identities.

The civil movement in Lebanon has largely limited itself to raising slogans, organising peaceful demonstrations, and maintaining a media presence. In 2019, widespread popular protests erupted across all regions of Lebanon in response to the deteriorating economic situation, calling for a change in the ruling political class. Although people began to regain hope for improving their living conditions, particularly due to the rapid decline of the economy, the street became divided once again, with a relative absence of a working-class movement. This division manifested between those who attributed the crisis to the sectarian system and raised liberal slogans, and those who viewed the conflict as fundamentally class-based. Ultimately, the civil movement produced little more than a group of deputies who referred to themselves as “change-makers,” most of whom remained affiliated with the ruling establishment.

Throughout all these years, Palestinian refugees endured insecurity and further marginalisation, both by the Lebanese authorities and the Palestinian leadership post-Oslo Accords. They continued to be deprived of their basic rights and services. Palestinian refugees have been excluded from key aspects of social, political, and economic life in the country, effectively isolating them within overcrowded camps that are controlled by military checkpoints and, in some cases, separation walls, as seen in the Ain al-Hilweh camp. Official agencies treat these camps as security hotbeds, where conflicts flare up intermittently, leading to the marginalisation of refugees who were once at the forefront of the national movement.13

In July 2019, the Lebanese Minister of Labour issued a directive that further tightened the already stringent restrictions on the employment of Palestinians in Lebanon, encapsulated in what the ministry termed the “Plan to Combat Illegal Foreign Labour.” In response, Palestinian refugees ignited a significant labour movement, termed the “Camps Movement,” to contest their systematic deprivation of fundamental rights. Spontaneous demonstrations erupted across all refugee camps, subsequently embraced by various Palestinian factions. During these protests, demonstrators underscored their status as residents rather than “foreigners” and strategically employed a tactic of popular boycotts against Lebanese goods in certain camps. This manifested in a striking scene where vegetables cultivated and bread produced in the Rashidieh camp were transported via trucks to the Ain al-Hilweh camp, symbolising a profound break from years of repression and marginalisation. Despite this assertive resistance, the movement faced challenges in transcending the confines of the camps and failed to garner sufficient solidarity and support from the broader Lebanese community. The Camps Movement persisted until it was eventually overshadowed by the uprising of October 17 of the same year.

The “Al-Aqsa Flood” and the Public Stagnation

Lebanese responses to the events of October 7 and their subsequent developments exhibited profound divergences. While some individuals articulated unequivocal animosity towards Israel, a considerable number distanced themselves politically and socially, asserting that the plight of the Palestinians does not concern them, provided it does not adversely affect Lebanon. Some perceive military engagement as adequate, while others express trepidation regarding such involvement.

For those unaffiliated with political parties, the “Al-Aqsa Flood” operation underscored their inability to formulate a political discourse that adequately supports Palestinian rights, even at a rhetorical level. In conjunction with traditional factions that persist in advocating for the normalisation of relations with the Israeli entity amidst ongoing acts of genocide, there exists an independent constituency that harbours disillusionment with the prevailing system and aspires for transformation. Nevertheless, this group grapples with the fear of endorsing armed Palestinian resistance, perceiving a fundamental conflict between preserving the “independence” of their nation and the moral imperative to express solidarity with and support the Palestinian cause.

Thirty years after the conclusion of the Civil War, political Maronitism continues to exert a significant influence in the construction of Lebanese national identity. Identity politics remain a dominant force shaping the interactions between individuals and their immediate and extended social environments. This contradiction manifests in the disparity between those actively engaging in sacrifice for the cause and those who profess to “distance themselves” from the conflict. Notably, this latter group has initiated a funded campaign titled “Lebanon Does Not Want War,”14 which ascribes culpability for the genocide of Palestinians to both Hezbollah and the Israeli state while professing neutrality towards Israel. Subsequent revelations indicated that this campaign was meticulously organized online and relied on the dissemination of content promoting internal narratives and international resolutions that align with the interests of the occupation, effectively undermining resistance efforts emanating from Lebanon.

This schism is observable not only in the declarations and political stances of Lebanese officials and media personalities, but also across social media platforms and news outlets. The rhetoric of neutrality has resulted in some expressing solidarity with Israelis or drawing false equivalencies between Palestinians living under occupation and their Israeli occupiers. Furthermore, others, leveraging their Lebanese identity, have posited that Lebanese citizens constitute the most aggrieved party in this conflict, thereby complicating the discourse surrounding victimhood and complicity in the ongoing struggle.

In this complex and contradictory context, a variety of movements advocating for Gaza have emerged within Lebanon, with the Free Palestine Front being the most prominent. This organization, established by independent activists as a reaction to the Israeli military operations in Gaza and southern Lebanon, actively orchestrated a series of demonstrations in Beirut. These protests encompassed actions that took place in front of the French, British, Egyptian, Saudi Arabian, and German embassies, in addition to demonstrations targeting companies on boycott lists, such as Starbucks and McDonald’s, and international organizations deemed complicit, including the International Red Cross. The Free Palestine Front adopts a radical stance, as evidenced by its declarations and actions, which advocates for armed Palestinian resistance and categorically rejects colonialism in all its manifestations, along with the dynamics of dependency and complicity with Western powers. Nevertheless, these demonstrations have encountered significant challenges in mobilizing large numbers of participants.

Simultaneously, the protests in the Palestinian camps fluctuate in intensity over time, as residents continue to boycott and obstruct the entry of goods that support the occupation. In contrast, certain Lebanese political parties initiated relatively modest demonstrations in collaboration with Palestinian organizations. While these protests may be numerically limited, they are notable for their mobilization efforts. However, collectively, these demonstrations fail to create a significant presence compared to those in other countries, which exacerbates feelings of impotence and frustration among many observers. Numerous individuals I engaged with expressed their dissatisfaction with the stark contrast between the prevailing normalcy in much of Lebanon and the apparent inability to effectively galvanize public support in the streets. To further elucidate this reality, I conducted several interviews with individuals actively involved in public affairs and socio-political work within Lebanon.

Rabih, who has a Marxist background and was active during the 2019 uprising, believes that Lebanese activists, especially those who emerged after the October 17 protests, have struggled to understand the complexities of the political landscape. He argues that they have failed to create a clear decolonial revolutionary discourse that opposes Israel and addresses the socio-economic needs of the working class, even though many align themselves with the left. Rabih attributes the lack of protests on the streets today to racist media propaganda that isolates people and focuses their concerns on narrow issues. He sees the current discourse as insular, often critiquing the Taif Agreement and fearing a repeat of the Civil War. Rabih views the inward focus on Lebanese identity as a colonial legacy. He argues that those trapped in this identity tend to direct their efforts primarily against Hezbollah, often sidelining the threat posed by Israel. He also points out that there is a strong individualistic and liberal culture, along with a lack of effective Marxist forces that could influence the political scene.

Rabih highlights the severe economic crisis affecting residents in Lebanon, which is described as the worst since the state’s founding. According to the World Bank, the poverty rate has tripled in the last decade. He says, “People are exhausted and see no hope for the future. There are constant efforts to stir up racism against refugees, which prevents any solidarity with Syrians or Palestinians. Additionally, many are unaware of how they can make an impact through boycotts or challenging Western interests.”

This indifferent political response to the genocide occurring at Lebanon’s borders, as well as the threats from its colonial enemy and the harmful rhetoric against Syrian refugees, shows how society has resigned itself to the identity of the ruling regime. Even Lebanese individuals who oppose the Syrian regime often fail to create a strong anti-racist message against Syrians in their country.

In discussing the role of the Lebanese people in the Arab-Israeli conflict, Khodor from the “General Student Union” argues that his identity requires him to be “not just in a position of solidarity but at the heart of the struggle.” He believes that this issue is not only about Palestinians, but it impacts the entire region. “Colonial powers see us as a single group they wish to control,” he adds. Khodor links the lack of mobilization and the sidelining of proposals that connect crises within communities to the nature of the Lebanese political and economic system and the broader colonial policies at play. He attributes this to the cultural dominance of liberalism and the rhetoric of political Islam, which often relies on religious rather than material arguments to understand the dynamics within society, focusing on Lebanese identity without addressing class struggles and economic issues that affect communities.

Interestingly, even in pro-Palestinian environments, there has been a noticeable lack of serious demonstrations and actions to support Gaza. Khodor suggests that this makes the current situation “worse than during the Civil War” regarding public discourse and engagement.

Cultural liberalism significantly contributes to the separation of issues and communities, fostering an individualistic culture that mirrors the dominant ideology of the contemporary West. This separation results in a noticeable lack of community solidarity and social cohesion. Consequently, in Lebanon, liberalism manifests not only as a political force but also as a social system and lifestyle.

The isolation of Palestinian camps in 2019 parallels the current situation in southern Lebanon, which has faced daily Israeli attacks since the previous year. Khodor posits that the absence of solidarity with Palestinians in the camps is often rooted in racist sentiments towards them; however, the similar treatment of Lebanese individuals in the south raises critical questions.

Khodor asserts the necessity of developing a counter-narrative to the prevailing discourse. He advocates for the establishment of discussions and knowledge-sharing sessions across various communities to connect the crises experienced in specific neighborhoods in Lebanon with the broader situation in Palestine. In this regard, the “General Student Union” has actively sought to challenge narratives that support Israeli occupation through both discussions and written material. The union has also allied with the “Free Palestine Front” in organizing protests, which included efforts to halt events featuring Western or Zionist ambassadors at local universities. Despite these initiatives, the overall response from the student body has been largely minimal or “silent.”

An Invisible Public Opinion

Khodor argues that the nation-state and its institutions have succeeded in overpowering society, leading to its fragmentation. While this perspective may apply to Lebanon, it seems less applicable to the Palestinian situation. The Palestinian community in the camps does not experience fragmentation or a lack of collective identity; instead, it suffers from a history of systematic isolation. The Palestinian community is deeply interconnected, characterized by social solidarity and a commitment to shared concerns, identity, and its cause. This sense of unity makes them less susceptible to the dominant neoliberal culture, yet their influence on the broader Lebanese society remains minimal.

Lina, a political activist raised in the Burj al-Barajneh camp, recalls participating in Palestinian demonstrations in Lebanese streets during her childhood. She finds it odd that such demonstrations have nearly vanished today: “The camp is completely separated from the city. I recently noticed just how much it is cut off. It has never been like this before, at least not in my memory or from what my grandmother has told me.”

For Palestinians, breaking through the barriers that separate them from the rest of society is challenging. This difficulty arises not only from security concerns and calls for neutrality but also from the ongoing and intensifying racist rhetoric that has persisted since their displacement. Sandy recounts an experience during a march against genocide in Beirut, where she faced verbal abuse from residents in a predominantly Christian area. Phrases like, “Get out of here, go back to your camps; you’ve made our country dirty” echoed around her. Sandy noted that verbal threats and intimidation regarding calling security forces were constant throughout the march. Such racial harassment has become a common occurrence at most rallies supporting Palestinians.

The absence of the anticipated solidarity in Lebanese streets is thus not surprising but rather expected. Fatima, a Palestinian refugee from the Mar Elias camp, highlighted the challenges faced while working on a campaign to boycott products that support the occupation. She found that the identity divide, coupled with the diversity of nationalities and backgrounds among residents, hindered efforts to achieve a large-scale boycott. “The situation in our country and the overall atmosphere don’t allow us to organize large movements like in other countries. The most we can do here is raise our voices,” she stated.

Demonstrations that successfully attract larger crowds tend to be those organized by Palestinian factions. However, both Fatima and Lina believe these factions are not fulfilling their responsibilities effectively. Fatima emphasized, “As long as the war on Gaza continues, the factions should be more focused on continuously mobilizing the streets.” Lina added, “The people who should be advocating for Palestine – organizations, institutions, academics, researchers, and journalists – are missing and not doing enough.”

From the Lebanese perspective, some individuals believe it is essential for Lebanese people to break the isolation surrounding Palestinians and re-establish connections with the camps, working to consolidate efforts in this direction.

Observing the streets offers valuable insights into the reality of the situation. The absence of demonstrations does not necessarily reflect the opinions of society as a whole. In various streets in Tripoli and Sidon, as well as in the western part of Beirut, images of Abu Ubaida, the spokesman for the Al-Qassam Brigades, can be seen. Additionally, signs and murals supporting Gaza are present, and discussions about genocide take place among the general public. Furthermore, fundraising campaigns continue despite the deteriorating living conditions. Fatima noted that these fundraising efforts, which originated in Lebanon, have expanded to include donors from various countries.

Lina argues that certain forms of solidarity remain unvoiced, particularly among Syrians living in Lebanon. These individuals face restrictions on their movement as refugees, which limits their ability to participate in protests. Furthermore, they encounter significant racism in various areas, further isolating them.

The absence of protests may also stem from a widespread belief that demonstrating is futile. Many young people Lina spoke with expressed a preference for joining the fight at the Lebanese-Palestinian border rather than engaging in peaceful protests. Palestinian demonstrators often chant, “Arm us, arm us, to the border, send us,” reflecting a desire for direct action. Some Palestinians have actively participated in the fighting in southern Lebanon since the conflict began. Fatima articulates this sentiment: “I wish we could go to the south and cross the border… What would happen? We die? It is better to die with some dignity.” Ghada from the Mar Elias camp echoes this frustration: “People are so angry that they want to go to the south, and my son is one of them.”

As residents of the camps observe the escalating conflict on the “northern front” and witness graphic images of destruction emerging from Gaza, they are reminded of their own prolonged suffering from years of displacement, violence, and blockades. Many feel a sense of imminent threat, convinced that the Zionist agenda of erasure will ultimately target them as well. “Today, it’s the people of Gaza; tomorrow, it will be us, and no one will care,” Fatima notes.

In light of the extraordinary circumstances confronting the region, one might conclude that history is repeating itself. We are witnessing ongoing divisions among people and the persistence of identity-based and isolationist narratives, juxtaposed with anti-Israel sentiments. However, there appears to be a notable absence of grassroots movements capable or willing to take effective action on the ground. The violence and suffering experienced have failed to mobilize student groups, traditional leftist parties, civil society movements, or feminist organizations in Lebanon.

By revisiting history and drawing lessons from it, we gain clarity about the current situation. The struggle of the Palestinians against colonialism is not only a fight for their own rights but also a call for the liberation of all oppressed peoples, particularly those in neighboring regions. Today, Israel exerts its power much like Western colonial forces did in the past. As it continues its violent campaign against Palestinians, it simultaneously threatens the Lebanese population. This serves as a stark reminder that confronting Israel and its entrenched influences within our communities, economies, and ways of life is not merely an act of solidarity. Rather, it is a pressing necessity that aligns with the interests of all people in the region.

- 1. https://180post.com/archives/14211

- 2. https://www.un.org/en/situation-in-occupied-palestine-and-israel/history

- 3. كلود دوبار وسليم نصر، الطبقات الاجتماعية في لبنان، مقاربة سوسيولوجية تطبيقية، مؤسسة الأبحاث العربية، بيروت، 1982.

- 4. جورج حبش، "صفحات من مسيرتي النضالية: مذكرات جورج حبش"، مركز دراسات الوحدة العربية، 2019، ص. 50.

- 5. https://palestine-memory.org/sites/PalestineMemory/Pages/DocumentDetails.aspx?DocumentName=12

- 6. https://palestine-memory.org/sites/PalestineMemory/Pages/DocumentDetails.aspx?DocumentName=1965

- 7. https://www.palquest.org/en/highlight/6590/palestinian-refugees-lebanon

- 8. The Nabatiye camp was completely destroyed in 1974, Tal el-Zaatar in 1976, and Jisr el Bacha in 1976.

- 9. صلاح خلف، "فلسطيني بلا هوية"، دار الجليل للنشر والدراسات والأبحاث الفلسطينية، 2016، ص. 191.

- 10. Habash, p. 264.

- 11. https://www.al-akhbar.com/Politics/237726

- 12. Habash, p. 228.

- 13. https://www.palquest.org/en/highlight/6590/palestinian-refugees-lebanon

- 14. https://alsifr.org/lebanon-does-not-want-war