Ephemeral Archive of Revolutionary Moments: Records from the Polish Feminist and Queer Protests of 2020

October, 2020: march through Three Crosses Square in central Warsaw

Introduction

In 2015, the conservative and right-wing populist political party “Law and Justice” (Polish: Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) came back to power in Poland. Since then, narrating, documenting, and archiving critical and oppositional activism in public life have become extremely difficult due to the repression of freedom of speech by the police and the judiciary.1 As a result, many grassroots and mainstream projects emerged to report on and create archives of resistance to the government. Among them are larger projects, such as journalist portals and social media or fact-checking services, as well as smaller ones that are focused on opposition protests, such as photo platforms, grassroots art exhibitions, or zine practices. Observing, thinking of, and participating in last year’s protests as a feminist, academic, and striker, I also wanted to join this collective outburst and create an autoethnographic archive of protests. Building on Julietta Singh’s No Archive Will Restore You, I tried to imagine the possibility of creating a collective and affective archive rather than an individual one. This desire was associated with the idea that the body’s relation to other bodies during demonstrations is especially unbound and entangled with the outside world, to invoke Singh’s words (2018, p. 29). I tried to think of the archive of the 2020 strikes as a story of intertwined resistant bodies, minds, and emotions. The desire to capture the revolutionary moments of last year was not only a wish to collect feelings on the streets, but also to archive the moments after the protests and before them, including impulses and motivations that brought people to the streets. More than delving into the archive itself, I found myself documenting the fragility, failures, and impossibilities of bringing such an archive to life.

The context and history of activism motivation

Before returning to the archive, however, I would like to take a closer look at the context of the 2020 protests. The pulse behind the last year’s demonstrations had to do not only to with the defense of reproductive justice, but queer solidarity also. More precisely, it took shape in the events that happened in Warsaw after the arrest of Margot, a Polish activist from the radical, feminist and queer collective Stop Bullshit (Stop Bzdurom). Margot had obstructed the course of PRO Pro-Life Foundation’s truck that paraded the slogan “Stop pedophilia” while blasting violent chants on megaphones, such as comparing non-heteronormativity with domestic violence or pedophilia.2 As a result, she was sentenced to two months’ imprisonment on charges of stopping the Foundation’s trucks. On August 7, protesters took to the streets in Warsaw in solidarity with arrested Margot; they chanted “when the state does not protect us, I will protect my sister” in front of the headquarter of the Campaign against Homophobia (Kampania Przeciw Homofobii)3 and later, on Krakowskie Przedmieście street. There, policemen pushed and kicked the protesters, before arresting them and moving them to detention cells.4 At police stations, activists were mentally and physically humiliated, denied access to water and medical care, and some strikers were harassed, according to a report made by the Representatives of the National Mechanism for the Prevention of Torture: “Most of the detainees were subjected to a personal check, which consisted of stripping them naked and forcing them to squat. (...) Some of the people who are on medication were not examined by doctors. The transgender person was deprived of access to testosterone, which, according to the recommendations of his doctor, should have been taken on the day of their imprisonment in the Health Care Center.”5 Because protesters were also refused legal aid, as a response to the situation, the Love Does Not Exclude Association (Stowarzyszenie Miłość Nie Wyklucza),6 Initiative Queer Tour,7 and Antifascist Coalition (Koalicja Antyfaszystkowska)8 co-organised a joint protest, where they displayed the slogan “You will never go alone! In solidarity against queerphobia”9 in front of the Palace of Culture on square Defilad. Queers and feminists gathered in the center of Warsaw in order to show solidarity with all queer people in Poland and denounce the out-of-control violence that the far-right government and the police perpetrated against the most vulnerable and marginalised.

Shortly after “You will never go alone!” the Polish Constitutional Tribunal banned abortions for malformed fetuses on October 22, 2020. On October 23, in opposition to the judgment, widespread demonstrations exploded and crowds of strikers gathered in front of the home of Jarosław Kaczyński, the leader of the Law and Justice party, at Adama Mickiewicza Street in Warsaw. Grassroots and informal, non-party initiatives of women, including The All-Poland Women’s Strike (Ogólnopolski Strajk Kobiet, OSK),10 organised spontaneous anti-government demonstrations. While these started on October 23, smaller protests had been happening since October 19, 2020, both in Warsaw and Krakow, taking various forms including car protests. The demonstrations lasted every single day until the end of October,11 in multiple cities in Poland and abroad.12 The All-Poland Women’s Strike gave the government an ultimatum until Wednesday, October 28. When the Law and Justice Party did not respond, October 30, 2020 saw one of the biggest protests for reproductive justice in Poland since 1989. Protests were organised in many cities and municipalities in Poland as well as around the world, and the international press widely commented on their scale: approximately one hundred thousand people were protesting in Warsaw alone,13 in what came to be known as the “Great March to Warsaw” („Wielki marsz na Warszawę”).14 The strong media and public response to the demonstration had borne witness to its relevance and to the widespread interest in the history of the Polish abortion bans, including the consequences of the 1993 Family Planning Act, which significantly limited access to abortion for social and economic reasons.15

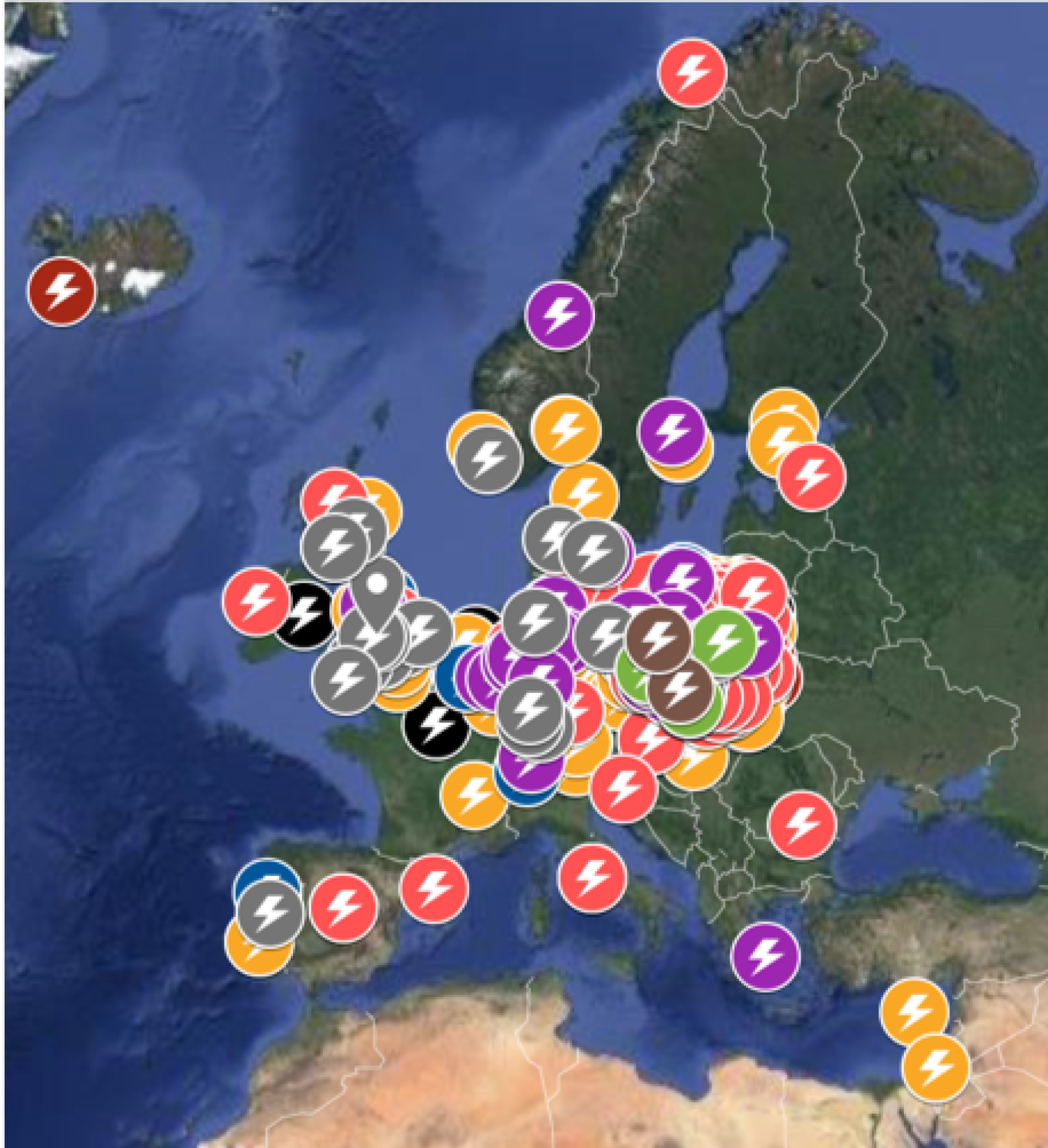

Both maps above show protests organised by OSK on October 30, 2020: the first one in Poland and the second one in Poland and abroad (mainly in Europe, however, protests were organised also in other continents including Australia, America, Africa, and Asia)16

The anti-abortion act of 1993 is crucial to understand the context and history of the 2020 demonstrations because the activist motivations that became visible in the last year go way back, since the early 90s. During the transformation era, the anti-abortion act was passed in Poland shortly after the collapse of the socialist regime when abortion was legal; it was the second law passed by the new government of Lech Wałęsa, a leader of the democratic opposition during the Polish People’s Republic, and a co-founder of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union “Solidarity.” However, protests around the adoption of the law of 1993, as Joanna Mishtal (2015, pp. 102-14) points out, took place on a small scale due to the absence of a dynamic feminist milieu prior 1989, consolidated around a specific goal, such as the protection of reproductive justice. During the era of state feminism in the PRL period, abortion was legal and common, as was the reimbursement of contraceptives and teaching sex education in public schools. Feminists did not, therefore, have to fight for these specific reproductive rights. Contraception only disappeared from the drug reimbursement program after 1989, the same way sex education disappeared from the public education program, only to be replaced by the compulsory subject of Catholicism by Lech Wałęsa’s new Catholic and conservative government (pp. 58-63). After the 1993 Family Planning Act, as Mishtal notes, further but unsuccessful attempts to ban abortions took place in 2007 during the conservative rule of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland, then in its 5th term (pp. 184-189), and again in 2016, when the raw bill “Stop Abortion” was submitted by the Ordo Iuris.17

The application for the registration of the “Stop Abortion” Legislative Initiative Committee, submitted to the Marshal of the Sejm on March 14, 2016, contained provisions in the draft amendment to the act calling for a complete ban on abortion and its criminalization (Nawojski, 2019, p. 5). In response to the bill, on April 1, 2016, lots of grassroots activist collectives created their profiles and events on social media, including the group Dziewuchy Dziewuchom (the name of the group is most often translated as Gals4Gals) that brought together thousands of Internet users within a few hours.18 On September 26, 2016, OSK created its social profile, began to establish local committees, and encouraged women to protest against the anti-abortion discourse forced by the Ordo Iuris bill “Stop Abortion.” In this way, OSK developed a nationwide mobilisation for the event planned for October 3, 2016, which went down in history under the name of Black Protests.19

Anger and emotionality of the protests

The scale of protests organised by the All-Poland Women’s Strike and other local collectives during the Black Protests in 2016 laid the ground for the protests of 2020. For example, as Greta Gober and Justyna Struzik noticed (2018, pp. 130-148), demonstrations, marches, petitions, and pickets organised by OSK in the framework of Black Protests mobilised not only those living in Poland, but also Polish women migrant communities around the world. Feminist transnational activism in action, as well as the role of the leaders of OSK in connecting people and narrowing the gaps between borders and protests, was a significant dimension of the mobilisations (ibid., p. 131). Gober and Struzik also point to the emotions that initiated transnational mobilisation in the context of the Black Protests and later protests organised around abortion (2018, pp. 141-142):

Anger and the emotionality of the movement were important factors that facilitated the activists’ decision to get involved in #BlackProtest organising. (…) emotions triggered by the events in Poland had driven #BlackProtest organising abroad.

For Gober and Struzik, the sense of responsibility, emotions related to personal biographical experiences, and anger were the driving force of the OSK actions. During the general mobilization, they influenced the formation and negotiation of a feminist transnational identity (ibid. p. 142-144). Thus, the protests organised by OSK helped not so much to shape feminist communities beyond national borders, but rather to abolish national borders between various feminist groups in different countries. This gave rise to a feminist structure involved in fighting for reproductive justice, as was apparent in 2020.

The geographical scale of abortion protests in Poland since the “Stop Abortion” Legislative Initiative Committee was formed, is usually associated with the scale of emotional motivations in the framework of feminist activism. As Katarzyna Iwaniuk, Aleksandra Knapik, and Małgorzata Wochowska (2019, p. 95) noticed on the pro-choice practices of the group Dziewuchy Dziewuchom from Łódź:

The attempt to prohibit abortion by law, pushed in the Sejm of the Republic of Poland by the Ordo Iuris Foundation (Korolczuk et al. 2019) in 2016, caused social opposition and thus mobilization of women in Poland on a scale unprecedented after 1993, when the law prohibiting abortion, except in exceptional circumstances, entered into force.

For Iwaniuk, Knapik, and Wochowska, the unprecedented geographical dimension of legal abortion protests in Poland was closely connected to their emotional landscape. An intersectional analysis of Dziewuchy Dziewuchom’s collective history indicates strikers’ emotional attitude toward the political and social transformations after 2016. These showed especially in the desire to change the situation of marginalised groups in Poland. As authors pointed out, motivations to the pro-choice actions were rooted in the private biographies of protesting women, in particular in the experience of post-socialist transformation or immigration to contexts where abortions were accessible during the 90s. They are also anchored in the local dimension of grassroots groups organising protests, including their logistical resources and communication capabilities. It seems especially important considering that all authors of the article “The Intersectionality Approach in New Social Movements After Black Monday” were emotionally involved in the protests, both as strikers and researchers. As Iwaniuk, Knapik, and Wochowska admit, they were born in Poland during the 80s, and although they do not know the times when abortion was free and available on-demand, they are in contact with their mothers, grandmothers, and aunts, as well as their friends and relatives, who all remember times with legal abortion on the one hand but rationed food and struggle for the end of Socialism on the other (ibid., p. 99). Apart from that, the three authors are members of the Dziewuchy Dziewuchom collective, which means that they participate in group actions as well as support and publicise other practices of resistance. Therefore, even though the authors do not mention autoethnography or performative ethnography as methodology in their text, their research is infused with these methods.

Authoethnography of the protests

In Changing the Wor(l)d: Discourse, Politics, and the Feminist Movement, Stacey Young explains that autoethnography “combine[s] autobiography with theoretical reflection and the author’s insistence on situating themselves within histories of oppression and resistance” (1997, p. 69). Recalling Changing the Wor(l)d, Lauren Fournier (2021) points out that in the sense of Young’s reflection, autoethnography defines a mode of writing that is rooted in civil rights and women’s movement. She also emphasises the embodied character of field research: in the framework of feminist studies, it discloses the critical awareness of the scholar’s position. Recalling Ellis, Adams, and Bochner, in Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism, Fournier (pp. 35-36) explains:

In autoethnography, one “seeks to describe and systematically analyze (graphy) personal experiences (auto) in order to understand cultural experiences (ethno)” (Ellis et al., 2011, p.1), turning necessary critical attention to oneself and one’s own position, while performative ethnography adds an awareness of embodiment learned in performance studies.

Keeping in mind these definitions of autoethnography, I would like to claim this method as an important part of my investigation during the pro-choice protests in Poland 2020. I participated in most of the protests as a woman, feminist, researcher, and cultural worker, with my friends, from October 23 to mid-November. In addition to the first protest at Adama Mickiewicza Street called by the All-Poland Women’s Strike “This is war!” (To jest wojna!), we also protested in front of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal, the Polish Parliament, The Presidential Palace, the headquarters of the national Polish Television, several buildings of ministries, churches, and houses of politicians from the Law and Justice Party. Together with thousands of strikers, we blocked streets and bridges in Warsaw from October 26 onward to issue an ultimatum to the government with demands for legal abortion, sex education, contraception, and the secular state. Apart from the demands regarding reproductive rights, we also called for the legitimate Constitutional Tribunal and the Supreme Court, that would protect women and queer people from violence.20 As a PhD student and worker in the cultural sector, I demonstrated with trade unions and signed several petitions and statements of the scientific community on the judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of October 22, 2020. A few times, I publicly encouraged their signature via email and social media. I also sent a formal complaint prepared by a team of lawyers cooperating with the Federation for Women and Family Planning to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg about the violation of women’s rights guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights in force in Poland.

During my participation in the protests, while capturing the moments by taking photos and short films, I also tried to collect collective memories and different intertwining feelings – both mine and people’s around me, in particular the anger that I personally very much felt. But in addition to the anger, we felt the anxiety that accompanied entering every single new street, because we had no idea how the police would react: if they would allow us to march through or if they would instead use violence and arrest us. After coming back home from the streets, I would make notes with sentences or associations stacked in my mind, and I was thinking of the possibility of creating an archive of revolutionary moments of queer and feminist protest from 2020 Poland. Yet, my archive appeared to be very fragile and ephemeral.

Collecting moments of revolutions

As Sara Ahmed notes in Living a Feminist Life, a feminist archive refers to the bodily way of moving around the world. It begins in the body: from the body’s contact with the outside world, from its corporal-emotional reaction to temporal (e.g. inability to cope with a task imposed by a given institution) and spatial (e.g. inability to access some place in public space) obstacles. Comparing feminism to a form of self-assembly, she explains (2017, p. 17):

I think of feminism as a fragile archive, a body assembled from shattering, from splattering, an archive whose fragility gives us responsibility: to take care.

She thus understands feminism as a kind of sensitive and fragile archive of relations, co-created on the basis of the idea of responsibility and concern. However, fragility, or even vulnerability, do not mean being deprived of willfulness, in particular in relation to the lesbian feminist practices of archiving (ibid., p. 222):

I want to think of lesbian feminism as a willfulness archive, a living and a lively archive made up and made out of our own experiences of struggling against what we come up against (…).

In this respect, while referring to Adrienne Rich, Ahmed builds upon the concept of a feminist vigilantism that means both practicing vigilance and caring, as well as resistance by striking, protesting, writing, demonstrating, opposing violence, asking questions, and questioning norms. In the context of social orientation towards heterosexuality, patriarchy, and racism, political confusion becomes praxis (ibid., p. 133).

Also, recalling Ahmed’s notion of fragile archive, Paul Preciado wonders how feminist, queer, and transgender knowledge can be embodied in collective experimentation and physical practice in Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. Criticising Giorgio Agamben’s concept of “bare life” (zoe), he emphasises that the body is not “bare” and does not have an unchanging nature (2013, p. 395). While analysing the relation between bodily experience and the process of developing knowledge, Preciado claims that we should think about the body as a techno-living organism, a biopolitical archive, and a cultural prosthesis. Therefore, an act of resistance should be the transformation of bodies towards the creation of an open, common, and living political archive (p. 389).

Thinking with Preciado who advocates the practice of trans-feminist micropolitics, described as copyleft gender politics, is especially helpful in the context of fighting for reproductive justice in Poland. The idea of Preciado’s copyleft gender politics means the pharmacological transformation of bodies is simultaneously a tool of resistance in order to create an open, shared political archive. Transformation of the body and resistance seem to be an important thought regarding the grassroots practices undertaken since 2016 against attempts to completely ban abortion. In 2020, in addition to fighting for access to legal abortion in public hospitals, we also demanded for abortion through pharmacological pills to become legal. Currently, feminist circles in Poland are practicing grassroots gynecology, by ordering pills such as Mifepristone and Misoprostol from abroad in order to have an abortion at home. In this sense, radical feminist gynecology joins Preciado in creating pharmacological common goods in situations where governments prohibit it. The best example of such grassroots, collective and cooperative activities of radical gynecology in Poland is the informal feminist initiative “Abortion Dream Team” which helps Polish women access safe pharmacological abortions and disseminates knowledge about it.21

Similar to Preciado and Ahmed, I would like to think about protesting bodies as a living and open archive of political moments. Through referring to the bodily dimension of the archiving process, both thinkers are thus expanding the idea of communal corporal-emotional roots on the one hand, and self-assembly or DIY aspect of living archive on the other. In Testo Junkie, Preciado mentions the copyleft gender politics; as for Ahmed, she uses metaphors of punk shattering and splattering in the context of feminist and queer resistance. Alongside the willfulness of rebellion and revolution, both scholars are aware of the fragility entangled in the process of bodily archiving. As Ahmed (2017, p. 163) claims:

Here, I want to consider fragility as the wear and tear of living a feminist life. Part of what makes diversity work “work” is the effort to find ways to survive what we come up against; to find ways to keep going, to keep trying, when the same things seem to happen, over and over again.

We can be shattered by what we come up against.

And then we come up against it again.

We can be exhausted by what we come up against.

And then we come up against it again.

No wonder: we might feel depleted. (...). By referring to “feeling depleted,” I am addressing a material as well as embodied phenomenon: of not having the energy to keep going in the face of what you come up against.

Drawing intensively from the thoughts of Gloria Anzaldúa, Ahmed emphasizes the potential that lies dormant in moments of emotional break. While describing the emotional consequences of a feminist struggle, she also contains the power of the load of feminist politics, which I understand as the effort to find practices of resistance in order to survive state oppression. Therefore, even though we felt exhausted, anxious, depleted, and shattered during the protests, every single day we were finding ways to keep struggling for reproduction justice again. Our work was resistance: it created, as Ahmed suggests, the feminist politics of fragility that told us how to survive and how to build relationships despite the breakable points, or indeed, because of them (ibid., p. 183).

Ephemeral archive of revolutionary moments

Almost a year after the queer and feminist protests of 2020, I have to admit that I questioned my assumptions about both the process and the results of collecting those moments of resistance. Even though I was trying to build an archive during my engagement as a feminist, researcher, and worker in the pro-choice protests during the last year, when looking at my records of revolutionary moments, I felt almost no connection with the photos, films, and notes I had gathered just a few months ago. It was as if I had lost my memory, or my archive no longer belonged to me since the abortion demonstrations in Poland had dwindled: it had acquired a completely new meaning. I felt the corporal-emotional consequences of the feminist politics of fragility Ahmed considers.

Since the Polish government started to loosen restrictions regarding the Covid-19 pandemic, I met more often with the people with whom I protested in 2020, including my childhood friends, as well as friends from my work and university. Remembering our presence at the protests, it felt as if all the memories and emotions – frustration, anger, fear – but also the desire for solidarity in resistance had suddenly resurfaced. In a conversation I had with my hometown friend, we recalled the demonstrations that had to do with the arrests of Margot from the collective “Stop Bullshit,” and pondered on our feelings just before the protest. We remembered that at that point, we had heard disturbing testimonies of numerous eyewitnesses at demonstrations: radical fascist groups brutal assaults and emotional humiliations, the police’s use of unjustifiable violence, security forces investigating people taking part in peaceful protests and arresting them later in their homes. Frustration, anger, and fear before the demonstration that day were closely associated with the homophobic repressions of queer people in the public sphere, and exacerbated by the violent political campaign spearheaded by the right-wing government.

Bringing memory and feelings back from 2020 through a collective process, together with my friends and simultaneously strikers, reminded me of all fragile emotions, including feeling depleted and shattered during the protests when faced with police violence and the confidence of fascist rioters ganging around the city. But it also reminded me of finding ways to keep trying, such as reading the recommendations on the pages and social media of Polish NGOs and LGBTQI+ groups, writing the numbers of grassroots lawyers on our arms, staying close together during these demonstrations. It was as if the archive had rebuilt itself at this particular moment of common recalling. As if I could only access to these moments when I recovered memory collectively, with people around me.

Through the experience of trying to create an archive of the completely grassroots and non-mainstream resistance movement, I realized how history is restored in the body: in memory and in rudimentary memories, through affects and emotions, beyond language and images. In this sense, bearing in mind the ephemeral and fragile dimension of the revolutionary archive, as Ahmed and Preciado make us think, the answer to the question of how countercultural history can be rebuilt would be the direction of collective and dialogical retrieval of history: the archive rebuilds and reconstructs with the people we protest in the streets with.

Photos of protests in October 2020 (taken by me). Top photo: march through Three Crosses Square in central Warsaw. Bottom photo: strike near the Archives of the Council of Ministers of the Chancellery of the Prime Minister at Belwederska Street.

Photo of protests on 26 of October 2020 (taken by me). Blocking streets and bridges in Warsaw near the Charles de Gaulle’s Roundabout.

Photos of banners and symbolic hanger prepared by my friend for the street actions in October 2020 (taken by me). Both banners illustrate graphics of red lightning propagated by Polish strikers and pro-choice groups, especially by OSK.

- 1. From the PiS assumption of power, the party has attacked the rule of law in Poland, from the attack on the independent Constitutional Tribunal, through the subjugation of the prosecutor’s office and the Supreme Court, to the failure to comply with the judgments of the Court of Justice of the European Union and the European Court of Human Rights. For more information see Free Courts Initiative Report: https://wolnesady.org/files/2000dnibezprawia_internet.pdf

- 2. The Foundation “PRO – Right to Life” was initially a typically anti-abortion foundation. In 2019, however, its activity focused on promoting homophobic content via vans driving around larger cities in Poland.

- 3. Campaign Against Homophobia is a nationwide non-governmental organization that prevents discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity in Polish society, and supports the fight for the rights of LGBT and transgender people. For more information see: https://kph.org.pl/

- 4. Marta Nowak, “She asked to be searched by the woman, the policemen took her. We heard her scream all the time,” OKO.press: https://oko.press/prosila-zeby-przeszukiwala-kobieta-zabrali-ja-policjanci-caly-czas-slyszelismy-jej-krzyk/ Marta Nowak, “The policeman pinned her head to the ground. They took her bleeding. A round-up of LGBT activist defenders is underway,” OKO.press: https://oko.press/trwa-lapanka-obroncow-aktywistke-lgbt/

- 5. “Representatives of the National Mechanism for the Prevention of Torture visits police places of detention after night arrests in Warsaw,” Official website of the Ombudsman: https://www.rpo.gov.pl/pl/content/kmpt-wizytuje-policyjne-miejsca-detencji-po-nocnych-zatrzymaniach-w-warszawie

- 6. Love Does Not Exclude Association is a national non-governmental organization committed to introducing marriage equality in Poland. For more information see: https://mnw.org.pl/en/

- 7. Queer Tour describes itself as a grassroots and non-commercial initiative aimed at visiting places defined as “LGBT free zones” and social education: https://www.facebook.com/Queer-Tour-102643847750287/?ref=page_internal

- 8. The anti-fascist coalition describes itself as follows: “We are a coalition of various people, organizations, projects, environments. We are united by opposition to fascism, its contemporary face: the extreme right.” Source: https://www.facebook.com/koalicjaantyfaszystowska/?ref=page_internal

- 9. Demonstration “You will never walk alone! // in solidarity against queerphobia” on social media: https://www.facebook.com/events/327968261895555/

- 10. The All-Poland Women’s Strike is a feminist independent social movement established in Poland in 2016. OSK was set up in protest against the rejection by the Polish Parliament of the bill “Save women” and the simultaneous referral of the project “Stop abortion” to work in the committee. For more information see: http://strajkkobiet.eu/co-robimy/

- 11. Throughout November 2020, people gathered in front of significant political buildings or walk in marches through cities, although more intensively during the first half of the month. Demonstrations started waning in the second half of November, before being reignited in January 2021 due to the Constitutional Tribunal’s justification of the abortion judgment, the contents of which were published in the Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland on 27 January 2021. For more information see: Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal dated October 22, 2020, file ref. K 1/20, Journal of Laws, 27 January 2021; source: https://dziennikustaw.gov.pl/DU/2021/175

- 12. Protests took place in over a hundred cities outside of Poland. Source: http://strajkkobiet.eu/mapa-wydarzen/

- 13. Anatol Magdziarz, Marc Santora, “Women Converge on Warsaw, Heightening Poland’s Largest Protests in Decades,” nytimes.com: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/30/world/europe/poland-abortion-women-protests.html Christian Davies, “Pro-choice supporters hold biggest-ever protest against Polish government,” theguardian.com: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/30/pro-choice-supporters-hold... Masha Gessen, “The abortion protests in Poland are starting to feel like a revolution,” newyorker.com: https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/the-abortion-protests-in-p...

- 14. However, the protests of October 2020 happened on a large scale, and not just in Warsaw. On October 28 for instance, the police recorded 410 protests across the country, in which over 430,000 people participated. For more information see: https://www.gazetaprawna.pl/wiadomosci/artykuly/1494857,komendant-glowny-policji-o-protestach-zatrzymano-blisko-80-osob-prowadzonych-jest-ponad-100-postepowan-ws-dewastacji.html

- 15. Act of January 7, 1993 on family planning, protection of the human fetus and conditions for the admissibility of termination of pregnancy (Journal of Laws 1993, No. 17, item 78), which entered into force on March 14, 1993.

- 16. Maps were created by the OSK. For more information regarding the OSK maps see: http://strajkkobiet.eu/mapa-wydarzen/.

- 17. For more information regarding the Ordo Iuris bill “Stop Abortion” see: https://ordoiuris.pl/stop-aborcji

- 18. Ibid. For more information regarding group see: https://dziewuchydziewuchom.pl/

- 19. Ibid. The name of the Black Protests refers to the color symbolism of the autumn demonstrations. On the one hand, the protesting women dressed in black wanted to mark the mourning and the symbolic loss of reproductive rights, and on the other hand, due to the weather, most of the demonstrators took with them – quite by accident – black umbrellas, photos of which went around the world.

- 20. The lists of demands presented by OSK as an ultimatum to the government are available at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/11NoAW_H1Jn7SHtkHDHm8quXBFnvOK9CoiR2jt8irwWM/edit?fbclid=IwAR10dF4bKxB2Tiaa7FUQ0DdOE2DLRIEbaWoMKuoOoGLu2HqRDOrF3k8jPCI

- 21. For more information regarding the initiative see: https://www.facebook.com/aborcyjnydreamteam/.

Sara Ahmed, “Living a Feminist Life,” Duke University Press, 2017.

Carolyn Ellis, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner, “Autoethnography: An Overview,” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12, no. 1 (2011): 1.

Lauren Fournier, “Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism,” The MIT Press, 2021.

Greta Gober, Justyna Struzik, Feminist transnational diaspora in the making. The case of the #BlackProtest, [in:] “Theoretical Practice. Feminist Movements in Central and Eastern Europe” edited by Kubisa, Wojnicka 4, no. 30, (2018).

Katarzyna Iwaniuk, Aleksandra Knapik and Małgorzata Wochowska, The Intersectionality Approach in New Social Movements After Black Monday – Practical Action and Analysis, [in:] “Women’s drowns 100 years of women's suffrage (1918-2018)” edited by Slany, Struzik, Ślusarczyk, Kowalska, Warat, Krzaklewska, Ciaputa, Ratecka, Król; Gender Studies UJ, 2019.

Joanna Mishtal, “The Politics of Morality. The Church, the State, and Reproductive Rights in Postsocialist Poland,” Ohio University Press, 2015, 102-104.

Radosław Nawojski, Calendar of Protests, [in:] “Female Revolt. Black Protests and Women Strikes” edited by Korolczuk, Kowalska, Ramme, Snochowska-Gonzalez, European Solidarity Center, 2019.

Paul Preciado, “Testo junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era,” The Feminist Press, 2013.

Julietta Singh, “No Archive Will Restore You,” punctum nooks, 2018.

Stacey Young, “Changing the Wor(l)d: Discourse, Politics, and the Feminist Movement,” Psychology Press, 1997.