An Archive of Queer Feminisms with Sara Ahmed

theod1_copy.jpg

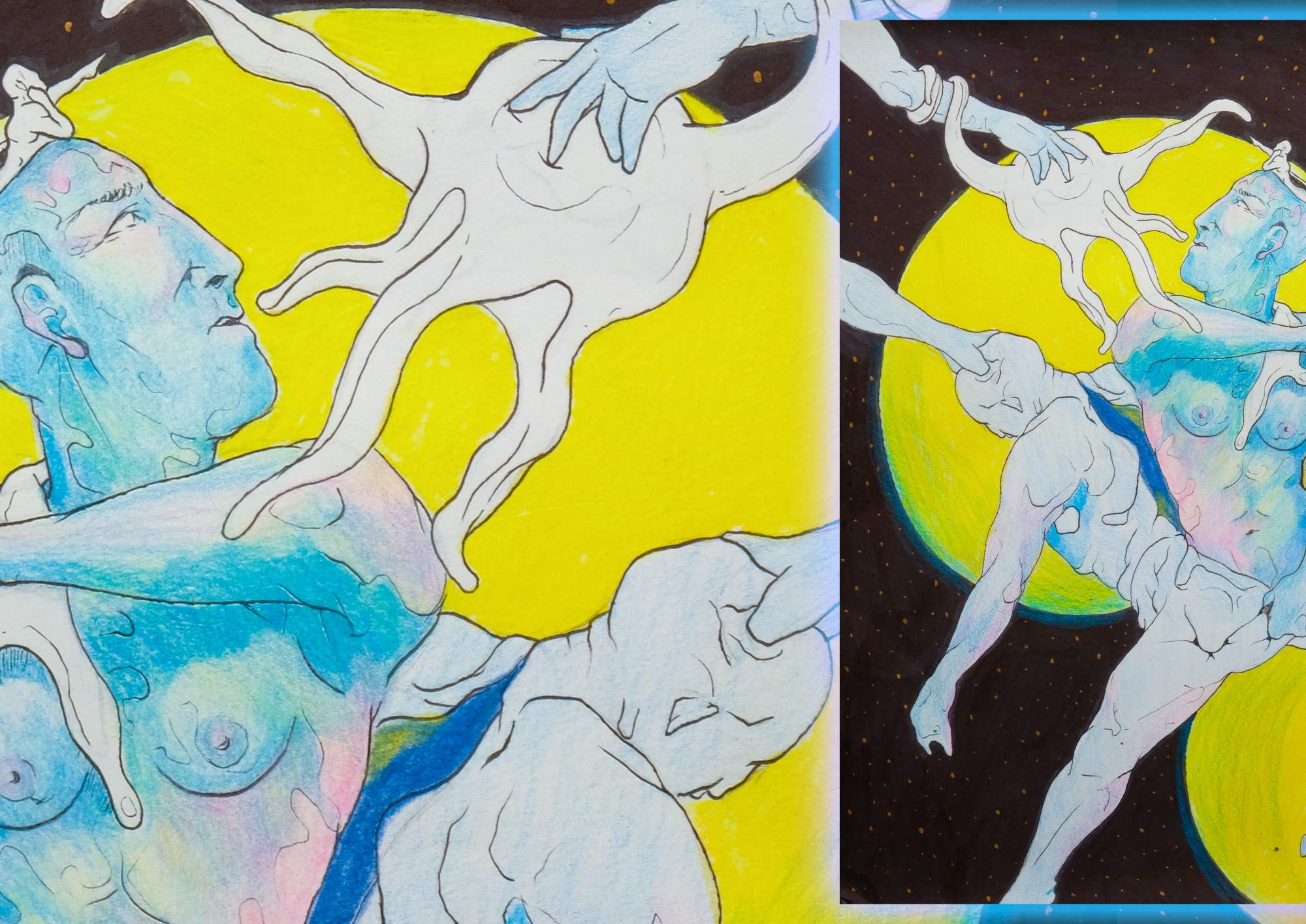

star shedding its skin

Sophie Chamas: Welcome and what an absolutely incredible turnout. We are really delighted to have this opportunity to celebrate Kohl’s inspiring Queer Feminisms issue with all of you today.

My name is Sophie Chamas and I will be chairing the event. I am a senior teaching fellow in Gender Studies at SOAS. Before I introduce the evening format and the panelists, I did want to say a few things about Kohl and about the importance of the Queer Feminisms issue. This issue was the product of a writing workshop that took place amidst revolutionary euphoria in Beirut. It was a product of a more hopeful moment and I hope that the archive trace of that moment in the pages of Kohl can really enliven and inspire us as we attempt to work our way out of this painful and debilitating conjuncture across multiple scales.

As somebody who teaches queer theory and queer politics, a question I always put to students is who does queer theory belong to and where can we locate queer theory? Too often I think we associate queer theory not only with the West, but more specifically with the North American academy. Too often we treat gender and sexuality in the Global South as data, and as data that needs to be made sense of through the interpretive lens and theory from elsewhere. The question that comes to mind in relation to an issue like this is can the global south not also articulate theory and can the non-academic also theorize?

These are the assumptions against which a platform like Kohl continuously pushes back. Kohl asks us to see the global south as more than just data, as more than just alternative knowledge, but as an invitation to rethink what we take for granted, to rethink how certain truths came to be and what counts as knowledge in the first place. And I also think that Kohl inspires not only an epistemological but an ontological questioning as well. It invites us to rethink what it is to be in and move through the world as a whole, rather than just a slice of it, and it invites us to draw on queerness and feminism from the periphery in order to deconstruct the center. So I think an issue like Queer Feminisms isn’t aimed at inviting us to place the forgotten or the ignored in conversation with what is already celebrated and theoretically normative, but it invites us to do a kind of displacing and decentering of what is already glorified as superior knowledge, and it asks us to embrace that which has been framed as an impossibility. Kohl in my view asks us not so much if the subaltern can speak, but if the subaltern can theorize, and the answer, of course, is yes, as we will see today.

I see the work of the authors and editors gathered here today as a crucial epistemological intervention with a really urgent political stake, and I look forward to thinking with them today about what queer feminism is, not just what it looks like in the Global South. I can’t think of a better interlocutor with whom to have the conversation about this issue than Sara Ahmed, and we are thrilled to have her with us today to discuss the potentiality of Kohl’s Queer Feminisms.

Ghiwa Sayegh: I will start with a litany of gratitude that cannot exhaust itself. I am indebted to the makers of this issue, to the Queer Feminisms workshop in Beirut that leaned into a revolution, and to Sara who gave us language to think and feel in as we came up against walls. I will say nothing new today; it is knowledge I was gifted with by the minds, visions, arms, and backs of those who have shaped Kohl, by our communities that make dreaming possible despite or because of how hard community is, by our transnational movements that are decolonial in their queerness, by those we have thought and raged alongside of, whether they know or sense it.

I left Beirut on August 24, 2020, 3 days before my 31st birthday and 20 days after the explosion of August 4. In Beirut, in my region of the world, across the South, we have lived cycles of industrial disasters, car bombs, missiles, police violence, state repression, economic collapse. We have learned destruction intimately; our bodies know destruction intimately. Yet, it was because of August 4 that I was authorized to cross the European border. The borders had been closed for months due to the pandemic, but this politics of exceptionalism meant that at that moment, some of us became worthy of crossing as narratives of misery, narratives that were mainstreamed and broadcasted in images that I will not reproduce. Kohl’s backbone threads with memory and resistance: we refuse to entertain narratives of misery. Instead, we turn to our queer feminist archive. Hence my question today: when do we become worthy of theory? Not as subjects to be theorized upon (the raw data Maya Mikdashi and Jasbir Puar talk about), but as living archives and those who inspire and conspire with us.

As I was writing this, I anticipated my hands would be shaking. Queer theory is about finding what makes you shake, what can make worlds shake. I am shaking because it is personal. And the personal is theoretical, as Sara Ahmed would say. With Kohl, we wrote queer feminisms every time a collective “we” breathed life into an issue. In a way, we were haunted by this issue before it turned into language. Publishing Queer Feminisms away from Beirut felt like grief. But we conjure the spaces and geographies that shape our political imaginaries every time I becomes we becomes theory. Our theories are queer because we carry them on our backs like a home, because we let them course through our veins and mark our flesh. Our queer is transnational rather than universal; it is southern, not as a geographical location we can point to on a map, but as the maps of our memory turned resistance. We are separated by nation-state borders; we are further isolated under lockdowns and curfews and halted mobilities. It makes me think of how theory travels, of how we think it travels. We have theorized abundantly, with our situated seeings and the knowledges we carry on our back and inside our flesh. But we say “theory travels” because the theories that we know and produce have historically been met with silences and walls. Theories are our praxis, but theory (in singular) as meta-narrative is that which has the power to write us out, even as we exist under its scope. Academia is one location; there are also institutions, our nation-states, the media, and the policies that get translated into border controls, global aid, state violence, social norms. Theory becomes a point of origin that is never ours to claim, regulated by publication standards we are not equipped to navigate, by languages and codes our tongues can speak but not master, by paywalls and degrees and bureaucratic processes and emotional labor that wear us down. So we write ourselves back into our narratives even as they are written by others; we tone down and edit out and conform in form and forms and structure. I/we forget that we were not “civilized” by global systems of power, by our nation-states, by institutions; we were disciplined. I/we forget that these systems, global and “national,” were put in place as projects of extraction. And so, as a queer phenomenology of theory, when we turn towards a point of origin, we have to look to our backs to point to histories of extraction. But when we came together for the queer feminisms workshop in Beirut, we did not speak back to; we spoke with each other and we allowed ourselves to shake. This is how we have always theorized.

I have told this story many times. Kohl has been doing this work for seven years. When Queer Feminisms came out last December, I felt frustrated it did not seem to stick. It is a question of reach. When we announced this launch, we were overwhelmed with online reach that was too widespread for us to contain, so we let it spill. I anxiously asked myself: by reaching out to Sara, was I and were we reproducing a hierarchy of theories? Are the political economies of circulation really outside of our reach? But perhaps that is not the story. That is not the reach we need to talk about. To know intimately with our bodies, we get messy with the systems that regulate our lives, our mobility, our togetherness. Perhaps Queer Feminisms, the issue, is the center of this narrative, because we have woven willfully enough to reach each other across the borders and positions we were assigned. We need not seize the means of production because we have always produced and theorized. I would like to turn our imaginaries to seizing the means of circulation. When we create our tracks of circulation, our queer archives reach across to each other; it is their mess and multiplicity that can make worlds shake.

Sabiha Allouche: thank you Ghiwa, thank you Sophie, thank you Sara, thank you everyone who’s present. I am a newcomer to academia, let alone to what counts as activism or praxis work. I often wonder: did I choose queer theory or did queer theory choose me?

The answer is not straightforward. Sometimes, I think I have been unknowingly gyrating around queer theory for the longest duration of my life, before it finally swept me in. Other times, I think I spent a life of perpetual irritation because something about our world just didn’t sit right with me, and by me here, I mean us. And before I knew it, I found myself surrounded by like-minded peers, the majority of whom I shall never meet, working together towards a there and then that are yet to be.

My life trajectory and situatedness has and continues to shelter me from the imminent violence and precarity that innumerable women, trans folx, forcibly displaced, settler occupied, and queer bodies find themselves in. I am a lucky recent graduate who found a permanent and full-time job two years from graduating. And I insist on luck. If my “work” has indeed led me to where I am, then it is imperative that we remind ourselves and everyone that feminist and queer writing are inherently collaborative. And by collaborative, I mean the irrefutable fact that they both emerge from sites of momentous violence. Flesh and feelings are part and parcel of the theory we produce, and to not transform our theorizing into praxis is to inherently betray the legacies of those who came before us and delay the there and then that we aspire to. (Or “for” I am not sure of the preposition).

When I imagine the there and then, I imagine this. I imagine, on our daily commutes, while preparing dinner, or whilst showering, listening to podcasts that historicize and contextualize and that dissipate intersectional knowledge. A sort of Top 10 billboard of agitational work, without the ranking of course, because we don’t like numbers. We need to disseminate the knowledge we produce. We are in the unique position that our academic endeavours cannot and will not be disassociated from activism per se. Perhaps, we need more YouTube channels and less journals. I embrace my work at Kohl, and I embrace my work at my university. I also mock the internal REF reviewer who scored my Kohl article out of all my submissions 2* out of 4 for lack of theoretical engagement. It is difficult to balance between open access work and high-flying academic journals. My gratitude goes, on this note, to the many names and faces in our audience who have at some point and time invested in the unpaid labor demanded to sustain Kohl.

Our lives’ trajectories are endless U-turns, re-orientations, recalibration and accommodation. What weighs on our minds and hearts is permanent. It lingers with us in the cinema, at restaurants, in the classroom, in the spa for some, on the beach, in airports, on hiking days and on lazy ones. Along the way, we sometimes lose friends and family members who have had enough of our killjoy attitude (of course, a nod to our discussant Sara Ahmed on this point).

We live in a world that bases itself on the speculations and affects of a fragile and at this stage farcical whiteness that is clearly, at least in my future-oriented wishful thinking, losing grip on itself: its reactions since the mobilizations that ensued from the killing of George Floyd range from that of a deer caught in headlights, to apocalyptic visions about a world where whites and non-whites live on par (what a calamity!), to increasingly clumsy and dangerous epistemic assemblages.

To our Kohl’s allies, the task ahead is long, demanding, costly, and relentless. In the end of the day, and for all the tensions that come with balancing identity politics with supranational injustices, we merely have each other. And to the younger among us, and by that I mean our authors Ahmed, Aya, Nour and Sarona, all the rest of our contributors, and to all of us intersectional queer feminsits out there, we stand in solidarity with your writing, practices and interventions. Thank you.

Sarona Abuaker: thank you to everyone who’s made this possible, from the workshop in Beirut to this moment. I am incredibly indebted to everyone who’s taken part in this process. Without you, this piece wouldn’t be here today. But I think some parts of me that are here today wouldn’t be here as well.

This piece came out of an attempt of sensing and recalibrating my senses around being shuffled, categorized, and interrogated, and out of a deep yearning for a home to be a safe place. This is a post-response to my piece – so if you haven’t read it, it will be a bit strange but I hope there is something in here for you.

I suppose what I have been thinking about is how we move, bring forth, and reside in safe intimacies. How much of that is a negotiation? It is a realization that a “running from” does not always bring forth an “arriving to.” Rather it shows the entanglements of our lives and how binded we are in relationalities. This isn’t necessarily a break away from a particular discourse around Palestinian-ness. Rather, it’s a way of looking at return and Palestinian-ness. I wanted to attempt to look at return not as a locked room, a car we are sitting in but not able to reach for the driver’s seat, a shore we are swimming to, a gift that must be granted, or taking on a rhythm that propels us backwards with the air whooshing into our ears as we fall into grounds we are already familiar with, or looking over our shoulders.

But I suppose it is over our shoulders – a fleshy specter, a humming. I live in London, and it is a noisy city – you get used to hearing certain sirens, certain words, on the streets around you. You become enveloped in these sounds, in these sonic wearings, and the iterability of them start wearing into your daily life – giving it shape like water to stone. When the first lockdown was imposed last year, the sound stopped. There was silence. There was stasis. What movement gives shape to our lives collectively when it is no longer being formed out of everything that surrounds us? And this is where I found myself inhabiting queer phenomenology. Return is not a space extended to us, and that forces us into stress positions in attempting to acquire a flexibility to reach it, to slip through the cracks, to rise up into it. If you pay $100 between at the Allenby border between the West Bank and Jordan, you are granted by the illegal Israeli military forces to skip the lines of people waiting, you are treated to hot coffee and a large room with leather seats, a private taxi taking shuttling in between checkpoints, finished off with a blue and white Bon Voyage sign overhanging in between palms trees upon entering Jericho. The first time I saw that sign, I almost vomited – straight hegemonic lines parading around as if they are extending themselves to us. But who is issuing the identity cards, who is issuing the policies, who is bringing in the vegetables and the fruits, who is controlling the water supply – these signs and dimensions of settler colonialism proliferate as time gathers, an accumulation. And whilst yes there are home demolitions continuing, our cultural productions continue to be seized, extracted/erased. There are now new ways of capitalism and settler colonialism to reach us, to allay us into false comforts – economic trade deals after Oslo privatizing sectors, welcoming capital and land brokers, creating new predatory ravenous settlements. Spaces/times/seats are not being open/not within reach yet we contort ourselves to fit – and emerging from that are incredibly painful and disorienting processes. Why should return be shaped by our pain, our bodies attempting to contort towards an object (a resolution, an institutional body, a soldier, a police officer, a debt collector).

“Return” is being shaped within a hegemonic nation-state capitalist mode. What is it exactly? Is it still return when there are people living in gated communities built by Gulf States whilst others struggle to feed their families, as long as the bodies that reside in those homes are Palestinian? Settler colonialism has become infused with extraction – that return is a mirage, a trap, a bank disguised as a home, the inside of an oil tank disguised as liberation. Try to take a deep breath in that atmosphere, and we too will suffocate like those men in the sun.

What forms of value are being planted, harvested, spread? Is return, a container, empty, waiting to be filled with Palestinians’ bodies? This is an attempt to grapple with this: return as a re-turning, not to a “back” but to a dimension – alive, breathing, and rebirthing, every day, by the efforts to not re-create the very relations that harm us and continue to harm us. And in this way return refuses to become organized, to become categorized. It becomes slippery because it continues to deviate away, spinning further out from the ideas and power-dynamics that are being committed right now in the name of nation-state-building, in the name of neo-liberal freedom. Return is not commodifiable. It is not for sale. And to go against this, to imagine, to practice, to relate against these ways that seek to commodify every aspect of our lives, every aspiration, and our futures, through new movements, that is where we meet and embody queerness in those deviations. And I look at return as “a way of world-making through new movements and senses. I want to change the feeling of return by re(turn)ing the possibilities of where return arrives, can be found, and where we can be touching it.” Thank you.

Nour Almazidi: It really is such a pleasure and an honor for me to be a part of this incredible event alongside so many amazing people and I’m so grateful for everyone involved in making this semi-reunion of Kohl’s Queer Feminisms workshop take place.

I want to take some time here to reflect on the piece I wrote in terms of the challenges that I’ve grappled with throughout this process of breaking down about methodology and queer feminist knowledge production more broadly, as well as the struggles that I’ve had to navigate in coming back to this piece under continuously shifting national political realities and pandemic conditions.

In this issue, I wrote about how queer life in Kuwait can be inhabited and lived in ways that are not only mobilized around questions of legal and political recognition and visibility, but are felt through time and space. So I wanted to give an account of spaces that are formed through queer social relations and attempt to language a phenomenology of this form of queer spatial intimacy without framing those spaces as inherently resistant or transcendent. So I situated myself in an analysis that takes into account the political economy of Kuwait and the classed apparatus of citizenship that structures so much of mechanisms of social and political control.

After our Queer Feminisms workshop had ended, coming back to this piece over and over again during those months of the editing process was incredibly difficult and so viscerally painful that I could feel myself embody a sort of refusal to do that work of revisiting and re-reading. For me, this refusal was shaped by a mourning, a mourning that asked me to question what it would mean for me to think about queer intimacies when I was so engulfed by my immediate reality of absolute state failure, and the classist structure of the state’s deadly temporality in response to the pandemic, alongside the intersectional vulnerabilities that are then exacerbated as a result.

On another level, this mourning was shaped by what Ghiwa says in her opening piece, that haunting mourning for the meeting table that we shared in Beirut. I wanted so badly to remember and to hold on to this generative feeling that we shared in that workshop, precisely because of how that space enabled another envisioning of how and where we can read ourselves, and the different ways queer feminisms, theories, and epistemologies could look like, and how those different ways didn’t need to ask for permission to be legible.

So much of what I struggled with was that question of erasing myself and my narrative from the writing. And so often I’d hear, “your voice disappears and we want you to come back.” I really held on to this idea of writing myself, writing myself back. And I held on to the encouragement of putting that anxiety in the paper – the anxiety around generative silences, the failures of language and articulation, the anxiety around who can do theory, questions of authorship and so on. At the heart of it, I think, queer feminisms and queer feminist knowledge production is driven by these displacements, myopias, and desires, and that in allowing ourselves to be read back into our work is to foreground that queer feminist archival yearning, that state of “wanting” and persistent desire, to think of that as a valuable way and mode of knowing. Thank you.

Sophie: Thank you Nour for those really powerful reflections about the anxieties and the loneliness that can come with producing knowledge and forgetting us thinking about sociality and camaraderie when we are trying to get over these anxieties and write ourselves into these texts and produce knowledge collectively. That was so beautiful, thank you.

Ahmed Ibrahim: thank you, and thank you everyone for being here.

When I began drafting this paper, I was already quite frustrated with academia, but still convinced somehow that it was my duty to insert myself and my ideas into it. I then went to the workshop feeling incredibly burdened by that duty, and worried I was taking someone else’s spot who was more deserving. I was overwhelmed because I felt that there was so much at stake in my head in what I was attempting to do with this paper, and I was terrified that I wasn’t qualified to deliver what I had promised in my abstract. And aside from what was going on in my life at a personal level, I was also all but broken by my university experience and had begun to feel completely disillusioned with academic knowledge production as a whole.

The workshop pushed me to dig deep into these feelings of fear and frustration and work through what they were trying to tell me. It really reminded me to trust the instincts that “rigorous scholarly inquiry” taught me to dismiss, and lead with the experience as opposed to what I hoped that experience would legitimize. And so I took the months afterwards to really ask myself what I wanted to achieve with this paper.

The workshop was the first time I felt that my words and my work were being taken seriously. And it was perhaps that experience of validation that helped me realize that it was indeed an utterly inconsequential academic form of validation that I was after for those 4 years I spent fleshing out this paper. In writing my final draft, it became clear to me that the people that I felt I wanted to write for not only knew what is at stake in being queer here, they also reap none of the benefits and all of the consequences of knowledge produced about their lives in the academy specifically but also elsewhere. It’s amusing now to think about how worked up I was about being “the only person writing about this” or “a good academic” doing “important work,” when I am at a point in my life now where I believe that there’s nothing less subversive than writing for the academy. I no longer feel that burden of making sure academia knows what queers in Egypt are living through, because again it strikes me now as precisely the opposite of those undergrad dreams of “revolutionary praxis.” In fact, it feels like I have given academia too much of myself and my collaborators in hopes we would get something back to sustain ourselves when in fact we always end up giving that to each other, perhaps because we are constantly confronted with the reality that that academia cannot, and that only we can. I am still incredibly grateful to have had an experience to write for Kohl because I believe that it is a model for queer feminist intellectual spaces in the region and I know this piece could not have been published anywhere else. And for that reason I am incredibly happy with how it is now, for what it is: an archive of a moment and a conversation that has been so profoundly influential in my life and that is still unfolding in front of me in ways I am figuring out as I go. Thank you.

Sophie: Thank you Ahmed for reminding us to ask whom we write for and what constitutes important work, but also for this really important and necessary critique of the violence of the academy and of the ways in which academia can devour and disappear rather than just produce. As somebody who is within academia, that resonates with me and I think it is an extremely valuable and important critique. Thank you.

Aya El Sharkawy: I want to start off by saying how happy I am to be here, how happy I was when I received my email from Kohl saying that I had been selected to be a part of this workshop. It felt like the kind of dream that I didn’t know I was allowed to have. Even then applying with my abstract, I felt like a little kid reaching for a shelf that was too high and I couldn’t believe that I actually got to have this experience. So thank you all and everyone who made this possible, for giving me a dream that I didn’t know that I had.

Basically, I came to this workshop with a paper that was originally like a genealogy of the term camp as it was situated in the western canon and as it was rooted in Susan Sontag’s theory. That’s what I came to the call for papers with. Immediately when I started speaking to Ghiwa, I was confronted with how much it could potentially grow. I think that has a lot to do with what we’ve been talking about: decolonizing these structures of knowledge production that are hegemonically western. And so even coming from here and producing queer theory, I was still producing queer theory that wasn’t local, that wasn’t my own, or that didn’t come from experience. That was maybe the first version of what I imagined this paper would be. And then I went to the workshop. I can’t describe what that experience was like. It was the dream that I didn’t know that I had. To be surrounded by so many people, so many Arab queer people, to be able to share that experience, be able to contribute to their work, be able to produce knowledge together – I think that was such an invaluable experience. When I left I had evolved into a different person because it was such an odd moment, coming straight from my undergrad into this world of writing and publishing. It was my first experience and I think I’m incredibly lucky. Maybe I’ve been spoiled because I don’t think it is always like this, but honestly the workshop was extremely life changing. So, the workshop was an incredible experience in Beirut at the time when we were going to riots and we were going to drag shows. It was an incredible experience apart from the part in the workshop that has to do with my actual paper. It was an incredible experience of shared knowledge production and of solidarity. I learned so much and I unlearned so much more. I think that that’s really important to highlight. It was almost like an uncomfortable unbecoming because I’m so used to a specific very rigid academic way of looking at things, and it is a very uncomfortable experience to remove yourself from that and to start feeling with experience or breathing with experience. So in the midst of riots, in the midst of drag shows, I just was having this unbecoming, and I think that I owe that to the workshop – this way of looking at the world.

I left Beirut with so much energy, with experiences I would carry forever, with memories that changed the way I would see the world and with very dear friends. That was the second version, I think, of the paper, that I was coming to. I left Beirut with something that was completely new. Then I had to work on it again and I was coming to it from very different experience than the first two. It was extremely difficult to come back to this paper because in the time since the workshop, it’s been so turbulent. There is the COVID virus and the fact that I am now inhabiting spaces that I thought I had escaped or grown too large for, navigating family structures that I thought I had figured out. This change in movement and temporality really led to a change in thinking. It was difficult to come back from that freeing moment of Beirut and be stuck back in a room that I thought that I had escaped by now. So, coming to editing this paper, for the last version that it was published then, was a very different experience; it was very sobering as compared to the very vibrant feeling that I was on when I was in Beirut.

Other than the COVID virus, there was Sara’s [Hegazy] passing at the start of summer. That really hit me hard because I think the only experience that I had that was similar to being in Beirut for Kohl was the concert in 2017 and Mashrou’ Leila. I was there, and I saw Sara raise the flag. That was a moment that was seared into my head because it was also a dream that I didn’t know I had. In the terror that followed, I remember being very affected and thinking very seriously about my privilege posit, thinking very seriously about queer theory. I think the first time I attempted to write queer theory was after Sara was imprisoned. I just want to mention that Sara’s passing in the beginning of last year in the middle of quarantine also completely altered the ways I was approaching the paper. Other than that there was a lot of political turbulence when it comes to sexual violence and combating sexual violence in Egypt. This summer has been incredibly productive I’d say but also very painful. We have learned a lot and we have lost a lot. We have paid high prices. But I think that it is one of the first times that a certain kind of activism has emerged maybe since 2011. So it’s a very interesting time to be also approaching theory and trying to write radical theory when you are in the middle of a movement. You approach it with a different kind of mindset.

Assault police and similar movements in Egypt to combat sexual violence and the subsequent violence and exposés that I felt entangled in definitely affected that way I was approaching this paper when I came to edit. Other than those things there was also the explosion in Beirut. All of our sudden our deadlines were being pushed and we had to call family and friends and people that became family and make sure that they were okay. There was also this idea of trying to reimagine these spaces that I had inhabited when I was there being, you know, completely altered, and this idea of being stuck in a completely different space but having the space that was in your memory be affected that way really also changed how I was approaching this paper. Not only the space that I was imagining when I was at the workshop no longer was, but also the memory of it was somehow affected by this explosion.

So in the midst of all of this, I was editing the paper. I came to it in a whole new light and I feel extremely grateful to be here after all of this changed, to be able to reflect on it two years later, and see how many different drafts and how many different versions and how it’s grown, but also to see how it acts as a kind of extension to myself, my experience – because I wrote it from experience – and to see it how it grows and how that reflects the kind of personality growth that I’ve gone through the past two years. Even just exploring the term camp itself and looking at aesthetics and that type of theory – because not all theory is about exposing the subject; sometimes you are writing culture, you are writing about fashion, and I think that’s the anthropologist in me – it was interesting to be able to produce this in the midst of all of this, and edit it in the midst of all of this change. I think that that really reflect in the last version of the paper that looks nothing like the genealogy based on Sontag that I had come to with. Honestly, the intervention that I think I made, I would not have been able to make if people like Ghiwa and everyone else at the workshop had not validated my voice and made me feel like I had something that was worth saying. That I did not need to parrot, you know, Susan Sontag in order to produce theory. That I also have the right to produce knowledge. I think that kind of validation is very important for me. I kept coming back to it when I was editing, and I feel like it was such an honor to be able to represent these beautiful images and be able to look at them and call them like the artifacts that they are. I feel extremely honored that people allowed me to interview them such as Anissa Krana, a drag queen in Beirut. I think that was one of my most life changing experiences, being able to interview them in the drag show that I went to, to see them. I think these experiences are invaluable and I hope that they all reflect in the paper. I feel so excited and so honored to be here to be able to answer questions and be able to talk about it and take it seriously again. And to be in the company of such amazing writers like Ahmed and Nour and Sarona, and to be in the company of someone like Sara Ahmed. So, I’m just extremely very grateful for those things.

Sophie: thank you Aya, that was incredibly moving. Thank you for taking us on this affective journey, from joy to pain, sociality to isolation, that has shaped the development of the piece and for reminding us of everything that is happening around theory when it’s being written, and that theory is being done in the world. That was incredibly powerful, thank you. Thank you all for your amazing interventions.

Sara Ahmed: Thank you so much, thank you so much, Sophie, and I just want to pause for a second because those presentations were just so moving. They really make me realize how much intellectual work we can do when we feel that work in our bones. It’s just fantastic, thank you so much.

Thank you so much for inviting me to be part of this special celebration of a very special issue on queer feminisms. I want to say to all the contributors how wonderful it is to have assembled this text, this material, this archive, this embodiment of a way of thinking and doing this queer object, this feminist practice, and this labor of love. It’s been a joy to spend time with the work. I did feel a little bit like I was hanging out with you all, because the words and the images that make up this issue convey so much about what came before it: the workshop, the chats, the laughter, the coffees being drunk. If the writing is what comes after, and writing always comes after, then the writing is a continuation of the work that came before. For me, working now as an independent scholar in a cottage in a rural area in Cambridgeshire in England – and yeah sometimes I wake up and wonder how did that happen? – and also in the times we are in when keeping one’s distance from others has become a way of taking care of others, it is easy to feel cut off from community, especially that queer urgent sense of community as what we need to assemble in order to fight for what we need. So, it’s been a real pleasure to feel the connections, both loose and lively and, in a way, to meet you in the words.

I just want to say something about the invitation that was sent to me by Sabiha and Ghiwa. You wrote that you would “introduce us,” and then you said “we are Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research.” And then you introduced me to the journal, though I had met you or met parts of you before, having read you before – what you do, what you publish, how you publish, the events you organize, grassroots events. And then you told me about the event, which you described as “one of the kindest and most cathartic events,” the workshop on Queer Feminisms in Beirut that took place in December 2019, that many people referred to already. And you said as well, “we ate, breathed, and bathed with queer theory.” How I love that description of queer theory as something else that we take in, not queer theory as we find in texts, although we do find queer theory in text. Not queer theory as what we debate although we do debate queer theory, but rather queer theory as a space or a zone or environment that we inhabit, in being with each other, doing what we do, living and loving as we do, those who hear in that word queer and its companion words something of ourselves, something of each other. It’s such a queer way of relating to queer theory, of relation as queer theory. So of course I said yes to the invitation.

In the introduction to the special issue, which is also written with such a sense of love and care, Sabiha and Ghiwa described how you created the meeting table you’ve been longing for, and I think Nour mentioned this table, and that those who stayed behind unwittingly mourned that table. I always notice tables – it is a little bit of an obsession I confess. I also tend to notice when they are missing. So we could think of this issue in itself as a queer table, not as a memorial table that has taken the place of a table that is missing, but rather as a queer table in a sense of enabling another way of meeting or meeting up or gathering, despite what happened after, despite everything: explosions, global pandemics. Perhaps gatherings matter all the more the more we are scattered. And I think that is what this work really achieves: it is, itself, a queer gathering, each contribution with its own point. So many queer points: to point to, to point out, to point toward, to point towards places – Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, Kuwait, Turkey, Pakistan, to spaces, cities, streets, coffee shops, hair salons, bedrooms, closets, doorways, to times, moments becoming movements, going back, returning, circling, a shattering of a timeline and its trauma, to bodies, camp, queer, wound, desiring, to feelings, grief as you described in the introduction, I love this “we reprogram our futures by recoding grief,” love, curiosity, and joy. I admire how you do not, to borrow the words in your introduction, “entertain the ghost of a white Europe,” by having, say, somber discussions of the whiteness of Euro-American queer theory, which is not to deny that there could be something quite entertaining about these discussions. But in a way to keep making that point can be to reproduce the same old citational paths. What if we were to create parts from our own struggles, for existence, where we are? I think this issue is an answer to that question showing us that we can create alternative pathways because you do create alternative pathways. Queerness does not have to be imagined as foreign, coming to us from the outside or from outsiders, nor as being in relation to whiteness and its versions of coming out with more or less explicit racialized tropes, from dark into light, from secrecy into publicity, from misery into happiness. Coming out can be narrated – I think we know this – as a colonial enterprise bringing unhappy brown queers and trans people from the closet or prison of culture into happy white queer communities. And I thank Jasbir Puar for helping us describe some of those logics, and also Camel Gupta, whose wise words at a workshop I am borrowing from here.

So, we can also follow our own ancestors, creating pathways by going back, queer ancestors, who to use terms from Maya’s (Bhardwaj) piece, “had the audacity to exist.” We might have different words for it; we don’t always have the words for it. An oft-used slogan in the UK is, “we are here because you were there,” we being brown and black folk from the formerly colonized countries. “We are here because you were there, we were queer before you were there.” Yes, there can be audacity in an existence. There, where, here, it can be quite confusing. So much of the writing assembled here is working from where, writing from where, with “where” being understood as complex, stable, unstable and yes, at times confusing. I was struck by how many of you share stories that help give us, your readers, a sense of “where” you’re coming from. For many of us, saying where you’re from is no easy matter. And of course, being asked that question “where are you from, no, really?” can be how you’re told you’re not from here, that you don’t belong here. But to work “from” can also be to work “on.” The more embodied our work, the more we leave traces of ourselves behind, so many traces, and also traces of the places where we have been. A book can be a place as well as a country, a city, a people, or a person, the more we face out toward others. So many of these contributions show us just what you can do with an “I.” An “I” can be a queer signifier slipping all over the place, and if you come into the text as you do, you bring with you so many histories, ancestors, certainly, also friends and families, and those you might have just chanced upon along the way. A text can be a table. To bring yourself into the text is to bring more to the table. I always find that so fascinating myself, that we can speak “to” by speaking “from,” trying to show where we are coming from, our identities as well as our arguments, as a way of opening up our relationship to others. For all this issue is shaped by how many of you took the risk of bringing yourselves into the text. It is also full of the difficulty of their actions. The stakes can be high. Some of us are called upon to speak about ourselves all the time lodged forever in the personal, or some of us might be assumed to be talking about ourselves whatever we’re talking about.

But what does it mean to bring yourself into the text when you’re being banished from your own home, or your homeland? Sarona for instance talks about being Palestinian in relation to being queer, living in multiple dimensions, not to be recognized by a state, inheriting a homeland that you are not in, that you do not reside in. To be dispossessed from a home and a homeland, from an inheritance, can be to be dispossessed from one’s own self, to live in a queer time, beside oneself. What then does it mean to return? Your words today were full of the evocation of that question, what does it mean to return? We have to return to return, to think of those affective disorientations that come from not being able to go back, not being able to go back without following the routes that take you away from something. Sarona’s emphasis is on how returning can then become a kind of “queer labor” to use your words, an embodiment of labor and work. Sarona also emphasizes how some doors might be opened because, say, of the passport that you have; other doors remain closed.

I’ve also become a little bit obsessed with doors. They are kind of like my new table. So obsessions can be about what we notice, or how we notice. There are quite a few doors in these stories. Doors can be, to borrow from Audrey Lorde, the master’s tools. We learn how the house is being built, by who is and is not allowed to enter. I think of Nour’s ethnographic account of police checkpoints in Kuwait. For queer and trans people, checkpoints can be spaces of harassment. If documents are checked so too our bodies, questions becoming instruments of surveillance. Are you a boy or a girl? What are you? Who are you? Some become suspect or suspicious because of how they present. We can be in these spaces where we are rendered suspicious. There’s such an acute and powerful description of this violence in Nour’s paper and really importantly I think, the story of sex and gender can be retold by traveling to a city. So categories, sex and gender say, can be spatial, and if so then, they come to be by being policed. What you have to get through to get through. Nour describes the checkpoint as “a space that highlights the unravelling of power relations within which subjectivities are constituted.” This feminist concern with power, the intimacy really of power, structural power, in other words the intimacy of structure, is shared throughout this issue by traveling through space, encountering others and police, other others. We are subjected to these systems of surveillance.

Closets too are spaces familiar to us from some queer writing as spaces we are in, until we are out. But there are many different ways about thinking about closets. In my own work on Complaint!, I considered for example filing cabinets familiar though silvery objects as institutional closets. So much data is buried here, and we can think about how we can be the data buried here, because of what that data would reveal, how that data might threaten the reputation of an organization, say, as being diverse, say, or a professor. Orientalism could also be thought of as a closet, an institutional closet. One utilitarian philosopher who wrote volumes on India without ever actually going there said he could find out more about India, and I’m quoting here from him, “from his closet in England” than by using his eyes and his ears in India. I think of that closet and all that is buried there, all the materials he put there. I think of universities themselves as closets. Who is buried here, all the material buried here? Maybe that is the stuff that needs to come out. Ahmed’s piece teaches us that the closet does not provide a space that is free from the violence of surveillance by states or by straights. Ahmed’s discussion of the closet draws in a quite extraordinary series of pictures of what coming out can entail by those they described as their long time interlocutors. Closets of course also have doors, and these doors can matter all the more, not because they are closed, because they stop us from getting in or from getting out, but because they can be opened. They enable us to be seen. Ahmed writes “the door is indeed always open, and the inner most intimacies of queer individuals are precisely what gets to be exploited by authoritarian heterosexuality.” So we might then have to find other ways of closing these doors, trying to stop ourselves from being seen by, in your terms, becoming “undetectable.” So doors could have queer uses, which is to say we find our own ways of shutting out what makes it difficult to keep going or to keep being. I admire how you convey that complexity of inhabiting the space of authoritarian heterosexuality through sound. I noticed especially the creaking as well as movement, and noticed especially the scurrying. Method, such as the use of visual prompts to allow people to picture something that is hard to convey in words or stories, can be how we become attuned to what is flickering and fleeting about queer and trans lives, to living lives that do not quite conform to what we are told we are, or what we are told we should be. And I thank José Muñoz here for his wisdom, his attention to the ephemeral.

Speaking of methods, what is striking for me about this issue is also the mix of methods across and within different pieces: use of ethnography, semi-structured interviews, documentation, the creation of archives and paintings and photographs and poetry, auto theory and memory work is dazzling. It’s beautiful. I appreciated so much this collection of materials, but also as well the care of your collective attention, how each contributor gave time to each quote, each image, each photograph, each picture. It is this care, I think, that gives us a sense of abundance. There is so much we can pick up because of what we see and how we see through a queer and feminist lens. I thought of that sense of abundance especially when reading Aya’s piece on Arab camp. I loved the assertiveness of your opening sentences, your willingness to make declarations about what Arab camp is. “Arab camp is excessive, is subversive is emancipatory, is visceral. Arab camp is queer and kitschy; it is at once naïve, self-conscious, and reflexive.” Aya’s beautiful collection of images is more than a collection. The collection is itself is a kind of crafting of camp, camp as queer innovation, creation, and ultimately joy. Aya’s piece also teaches us how Arab camp is all the more inventive because it is not part of the canon. You write, “having lived it, seen it, consumed it, met it, worn it, and conversed with it, I am certain that camp has been inhabiting spaces outside of its canon.” Lived it, seen it, consumed it, met it, worn it, conversed with it.

I think back to how I was invited to join this queer table. “We ate, breathed, and bathed with queer theory.” Congratulations once again to all of you for all you have given us in doing just that. Thank you.

Sophie: Thank you so much Sara for that. That was such a loving engagement with the issue and with the contributors. I was really struck when you were speaking about this idea, these traces of love and joy and this haunting of care that surrounds this issue and that makes these texts really what they are. That was such a wonderful reflection, thank you so much.

Sabiha: I just want to take the time to say, it was a big deal, the workshop. And sometimes I feel I was very lucky to be there. I think in 10 years, it is fair to turn back and think about this workshop as a big deal. In that sense I feel I was very lucky to be there. It’s literally that. I remember Aya bringing the book of the theorist with her to the workshop, and everyone was like, nobody needs the book, you don’t need the book. And it seems to have paid off. It’s good, it’s a good feeling.

Ghiwa: First of all, I have to say that all the interventions really made me emotional. Thank you so much for bringing yourselves into, first Kohl, and also this event. It means a lot when we are separated because in a way, I feel that this event should have happened in Beirut with all of us being together around the same table. Unfortunately, it’s not today, but hopefully soon. I think I want to share some reflections about the notion of authenticity and creating our own paths. I think that this is the work that Kohl has been trying to do for quite a while – the path part, not authenticity part. We are in and out systems of control, of systems of power, of institutions etc. And so, we cannot claim to an authentic position because this is very much part of the work that we do. For this I go back to queer use, to “A Mess as a Queer Map” that Sara Ahmed drew and shared on her blog. And I realize that to find our paths, to find the tracks, we need to go through this mess of facing and being side by side with, being complicit with, whether European whiteness or academia, but also the systems that we are part of, the nation-states that we live under, the privileges that we are given when we are able to move from one place to the other, and all of these questions that those different geographies bring about, not just in the geographical sense but also in the political imaginary that we share once we move from one place to the other. Like Sara said, it could be a book, it could be a physical place, it could be a community and an imaginary. And so, what do those paths do to our understanding of creating the circulations I was talking about? Often the answer is not straightforward. It takes work, and it takes reaching out which is what we are trying to do today.