The Women of TikTok: Their Freedom is My Freedom

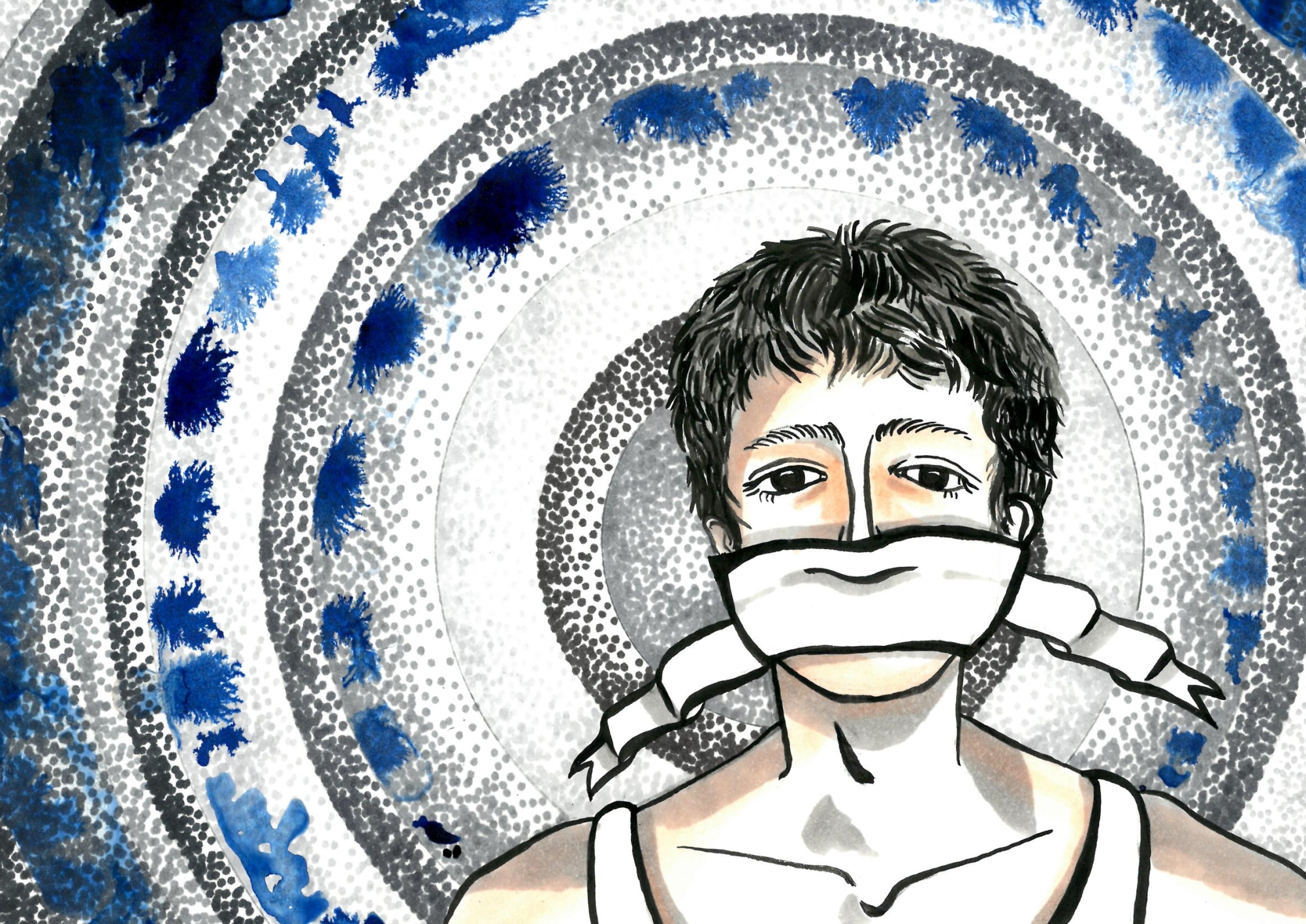

speak no evil

Our Bodies between Gender and Class

Last April, a systematic crackdown targeted women content creators on the social networking site TikTok in Egypt. It started when a group of men content creators on YouTube, including renowned Nasser Hekaya, selected a number of women content creators on TikTok, defaming them and inciting against them. As a result, a team of lawyers submitted a legal notice, including A.F., who launched a coordinated social media campaign with the hashtag #خليها_تنضف (clean/sanitize -it [Egypt]). Following the notice, prosecutors swiftly issued arrest warrants, detaining Haneen Hossam and Mawada Eladhm, followed by Menna Abdelaziz and Sherry Hanem with her daughter Zumurroda, in addition to Manar Samy, Rina Imad, Hadeer Elhadi, and Bassant Mohamed. Three of the nine women’s cases were referred to court: Haneen Hossam and Mawada Eladhm were sentenced to two years in jail and fined with 300 thousand E£, while Manar Samy got three years of imprisonment, 300 thousand E£ fine, and a 20 thousand E£ as a reprieve of penalty pending an appeal.

With the TikTok women, the interwoven, cooperating forces of patriarchy attempted to set an example and sent a clear message: if you don’t self-censor and if your family doesn’t keep an eye on you, we will; we will use every weapon, rhetoric, and established principle to punish you. This power is not concentrated in the state’s alone; it also encompasses men content creators, aggravating media, lawyers prepared to report, prosecutors releasing arrest warrants, and an unconstitutional hollow law with hurried sentences. It also includes corporations like YouTube profiting off of instigating content, and the National Council for Women (NCW), the alleged embodiment of feminism in the country that wasn’t interested enough in the TikTok women. Patriarchy and its institutions use our bodies as women as sites of domination and control. With every boundary and rule we need to follow – when to speak, when to walk down the streets, or even when to sit in our homes with our fathers and brothers – our bodies become burdens, and any digressing interaction with ourselves or our bodies is systematically punished. Contextually, such acts of dominance and power are exerted through the sexual violence of male entitlement that gives men the right to control all non-masculine bodies existing in their spheres. Male entitlement also entails the desire to punish by harm, using sex as a form of violence against women.

Under the heteronormative patriarchal system, sexual violence is based on the perception of sex as an act of male virility and submission from the part of women’s bodies rather than an act of pleasure. In this sense, sexual violence emerges as one of the many reflections of a violent and controlling patriarchy. What Menna Abdelaziz (Aya) was subjected to is an embodiment of this dynamic: on Friday, May 22nd 2020, we woke up to a video of a seemingly young girl, sobbing with a bruised face, recounting being raped by Mazen Ibrahim who, with the help of other men and women, assaulted and filmed her, and threatened to share the video online. Menna pleaded for the help of the community and asked for support: “I want justice.” We cannot ignore the fact that what happened to Menna occurred directly after the arrest of Haneen Hossam and Mawada Eladhm. After Menna shared her story, Ibrahim (the rapist) posted a thread suggesting that Menna wasn’t a virgin and calling people to watch her TikTok videos as a justification enough for the rape, considering it deserved. Not only was she raped, but she was charged by prosecutors. Despite her aggressors being referred to court, Menna is still detained. The prosecution decided to replace a pre-trial detention with another precautionary measure and confined her in a shelter for abused women. According to the prosecution’s statement, the decision was taken due to Menna’s need of “rehabilitation.”

In a society dominated by patriarchal consciousness, women are perceived the origin of temptation: they are viewed as the reason for all sins, and the violence they face as a logical consequence to their behavior. In one of his inciting videos against Mawada Eladhm, Nasser Heyaka says: “young men’s desires would certainly be provoked watching this debauchery.” From his standpoint, the TikTok women are destroying our social values and principles, and it is the duty of the men and the institutions of this society to “teach them a lesson.” This prominent collective consciousness in our society also sees sex as shameful, due to all the complications surrounding it; women must hide and tread lightly, as they are always accused of instigating and committing sin. This is evident in the wording of news taken from the attorney’s (A.F.) relentless reports against these women, calling for their arrest. The seditious content and reports are but a reflection of these men’s sexual fantasies. For instance, one of the news reporting the filing of a new suit against May Mohamad portrayed her as “…wrapped in a U.S Flag, naked.” How did the lawyer, the YouTuber, or the reporter know that she was wrapped naked? Or was it what they fantasized about looking at the picture? Did they wish she was naked underneath the flag? I believe that these men, whether inciters or informers, were aroused by the pictures and videos, yet ashamed and confused by their own arousal. Thus, they blamed women content creator who did not treat their bodies as burden as dictated by patriarchy, in order to exonerate themselves from this obsession.

Not only did the TikTok women break the prominent social norms in Egypt by being visible, but they also challenged the socially accepted moral code for women of their social class. We therefore need to deconstruct the concept of class. Some of the TikTok women currently detained were said to be rich and owning property, as opposed to coming from middle or working classes. Yet, class is not only defined by money or material capital, but also by other forms of capital such as social. Women coming from middle or working classes count among their social capital their families, neighbors, or friends who support and accompany them in their daily lives. In other words, their social capital is their network of relationships that provide for their social needs. However, the value of this capital is determined by the inherited wealth of one’s family, which brings about a network of powerful and influential people and corporations. When you’re the daughter of a rich, influential family, you also inherit a network of social relationships accumulated over generations, resulting in a social status with a bigger margin of freedom and support whenever needed.

Simultaneously with the arrest of the TikTok women, a group of upper and upper middle class women raised the case of #ABZ (the predator Ahmad Bassam Zaki) on July 2nd. A series of anonymous testimonies accused Ahmad Zaki of the harassment, assault, and rape of over a hundred women. The testimonies mentioned that he also digitally pursued and threatened many women. The reaction of the general prosecution and the NCW was very different from their interaction with the TikTok women, including Menna Abdelaziz. Calling into the show of television host Amr Adib, the president of the NCW asserted that they “contacted one of the women (ABZ rape case survivors/victims) … We are following up with the general prosecution’s office. The council will be filing reports, so we encourage the women to come forward. We’re beside them and we will provide all legal support needed; we call on them not to be afraid and to report.” While completely ignoring the prosecutors targeting and detaining TikTok women, she continued: “I can’t talk enough about the support and relentless work of the general prosecutor.” She even reassured the survivors/victims of this case with the protection of their privacy. “Even if you were engaged in a sexual act with this person and you change your mind halfway, but he forces you to go on against your will, that is also rape,” was the prosecution’s response to the first survivor in the first report submitted against rapist Ahmad Zaki. But the women of TikTok were not from an upper social class; they do not come from families with power and influence, so the NCW did not bother to issue a statement addressing the systematic crackdown they were facing. None of them was offered any legal support, and voices demanding their justice fell on the council’s deaf ears. Instead, the council shared a post on its official Instagram and Facebook accounts raising “awareness” on the need for women to be aware of laws condemning acts that “violate Egypt’s family values.” Similarly, the general prosecution, in its statements of all the women detained on the account of their TikTok content, defamed these women and doubted their honor, considering it the easiest way to socially destroy them.

For women with no material or valuable social capitals, “honor” is a valuable capital in our society. Honor itself represents a broad heavy concept for women to carry alone; if one of us slacks it is on the men of her family to punish and discipline her, and if the men of her family fail to do so it is up to the men of her neighborhood. Honor is linked with reputation, and reputation is built through the judgement and words of the entourage. It often depends on our behavior as women and how well we abide by the social norms placed on our shoulders.

Following the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo back in 1994, and in the scope of her work on sexual and reproductive health and rights, Aida Seif Eldawla first used the term “trade-off” to describe the daily negotiations women have to go through, compromising some of their physical rights to receive more significant and crucial rights for them in return. As a case in point, she pondered on the local wedding night tradition “such as showing a bloodstained towel the morning after the wedding night:” why do women accept such humiliating practice? For some women, this practice is a compromise to gain the freedom of movement and being out in the streets late at night. Accordingly, we can see how “honor” and “reputation” function as capitals for women – particularly middle and working class women, who can then trade other rights in return that might be more significant to them. However, given the fact that honor and reputation aren’t physically determined facts, they don’t make a solid capital a woman can rely on. In fact, our reputation depends on the judgment of our environment, susceptible to be smeared with a word or a rumor, which makes reputation an unreliable and fragile capital with social advantages if present, and punishment if it opposes people controlling it.

Demonizing the TikTok women was an essential part of the media coverage of the case. They were carefully depicted these women as provocative, showcasing socially rejected behaviors women should avoid. For instance, one story highlighted the fact that “Mawada Eladhm left her family three years ago,” which is the exact point Nasser Hekaya underlined in one of his videos, saying: “she strips and makes video content; she went to Cairo and left her family for this business.”

Our Self between Family, Society, and State

Most of the TikTok women were accused of violating Egypt’s family values. Two of them were sentenced to two years of imprisonment with a 300 thousand E£. Meanwhile, the prosecution ordered the arrest of the Fairmont rapists1 after seven of them managed to flee the country despite a month and a half of constant demand on social media to arrest them. It is worth mentioning that the Fairmont case was raised on social media in July of 2020. Judicial bodies and the NCW, who fight against sexual violence in Egypt, did not see that Egypt’s family values, allegedly threatened by women on TikTok, are the same values that enable the violations of our bodies. We are put through FGM, marital rape, child marriage, battery, captivity, and virginity tests. These do not threaten Egyptian family values; in fact, they are all practices originating from these same values in which men are raised with the entitlement of owning the bodies of women around them to control and rectify at will. Family is where oppressive social norms reproduce themselves first; it is where we first learn that our bodies belong to our fathers, mothers, relatives, and neighbors, but not to us, and whatever violation we’re subjected to is our fault. Patriarchy demands institutions to regenerate its principles and hierarchies to function, and in that regard, family is a primary institution of the patriarchy. It is the site that sets behavioral patterns outside of the household: what to wear, what to say, how to walk down the street, how to talk to strangers, etc.

It is no news that the state is interested in keeping family as an institution, making sure it tightens its grip on its members. Historically, the Egyptian state – like other states – has used the model of the family to control women’s bodies, directing them towards a reproductive path in line with its demographic policies and production demands. Family was the primary unit where the modern national state could collect and classify people, monitor the different reproductive patterns in different social classes, and develop particular policies to control women’s reproductive health. Family is what makes society cohesive: if controlled by the state, society as a whole is controlled. Therefore, the absolute freedom of women and control over their bodies is detrimental to the state. The TikTok women’s casual approach to their bodies threatened this structure; in turn, it made an example out of them. Over the years, Egyptian constitutions included the article that reads: “family is the basis of society and is founded on religion, ethics, and patriotism.” This article portrays the ideal family as seen by the ruling class, with the state at its heart. But ethics is an elastic term with no bounds to define; it varies according to one’s social background, upbringing, class, work, and province. Even religion lacks particular definitions when it comes to ethics, with diverse interpretations over the years, according to different sects, social background, and interests of its scholars. I ask myself, what religion? What ethics? Patriotism certainly completes the trinity of authoritarianism. It is inseparable from how women are perceived as representing the “Image of Egypt.” Nasser Hekaya references this portrayal in one of his videos: “people (TikTok women) are smearing the image of our society and disgracing the name of Egypt.” Consequently, laws punishing the TikTok women are an extension of a long history of the state’s use of families as a key to assert its control over society.

This power is now threatened by an innovative space allowing women to exist with more freedom and less personal censorship: the internet. As women, our existence is now extended between two realities – the physical and the digital. They are both part of our entity, nurturing each other to form new frames of being. The digital reality is a new world with no clear confines but with vast spaces for expression and being, where women established their presence unregulated by socially “acceptable” behavior. Women might even exist more loudly in the digital world than in the physical one where censorship – the state’s or the family’s – and the possibilities of physical violence are lesser. Additionally, the internet played a major role in breaking the barriers between the private and public spheres. We can watch a video of a woman from her own home, her own kitchen, in her home clothes, sharing random thoughts on life while preparing dinner for the children. One of patriarchy’s foundations is separating those two spheres, transferring women – bodies, minds, and souls – to the private sphere, and portraying the two as disconnected. This, in turn, reproduces the trope of the compulsory hiding of women.

The digital reality has become a new field of work with no prerequisites, no experience required, and tools available for the majority (a camera phone and internet access). It is a field for those with no opportunity for a typical job with payroll. The unconventional presence of women online and their widespread ability to use it, gain followers, and get paid overwhelmed Egyptian men – the YouTubers, lawyers, prosecutors, and judges – with the feeling that the status quo is about to collapse. It is evident in another video of the YouTuber Hekaya, where he appears to be upset with the lack of parental censorship over these social platforms: “of course, the mother is out in the hall, oblivious to what her daughter is doing. She would tell her mother to close the door because she’s busy – she’s working from home. The mother doesn’t know what’s happening in there. Meanwhile, the girl would change into something light and cover her face to only show her body.” Ironically, Nasser Hekaya is talking from his room with his bed appearing behind him under a dim blue light. In a statement following the arrest of Haneen Hossam, the prosecution referred to the internet as a “fourth border beside land air and sea (…) a new cyber frontier in the digital sphere that demands strict restraint and precaution to be guarded like other borders.” This constituted the framework of the general prosecution’s call for preserving the “social national security” after Haneen’s alleged violations of Egypt’s family values.

If the Egyptian Family Allows It

Under the hashtag #بعد_اذن_الاسرة_المصرية (if the Egyptian family allows it), a group of anonymous Egyptian women launched a sarcastic campaign that reflects the absurdity of the charges against the TikTok women and the underlying bond between family and state. The campaign launched a petition that demands the release of the TikTok women and the legal support of the NCW. The group highlights the systematic crackdown on these women, also referring to the classist discrimination and oppression against the TikTok women that manifested in the way national bodies like the prosecution and NCW handled their cases in comparison to other files like #ABZ. Up until this moment, while writing these words, the petition has gathered over 140 thousand supporters, and the hashtag has widely spread on Facebook and Twitter. The initiative created original designs, and different creators contributed to the campaign through Facebook posts and tweets, arguing against the custody enforced on women’s bodies, the power dynamics in families, the resulting burdens and violations, and the current rise in cases of sexual violence. In one of its blogging sessions, the campaign focused on the NCW by tagging their twitter account demanding legal support for the TikTok women. To this day, the NCW hasn’t released any statement addressing the crackdown. Moreover, a wide group of supporters shared the profiles of the nine women for a week, introducing the each case, while other women shared their videos dancing with the hashtag “dancing isn’t a crime” #الرقص_مش_جريمة.

Why am I Involved?

The women of TikTok occupied spheres I couldn’t occupy myself. My social media presence is akin to that of an observer after being active for a while, unapologetically sharing my thoughts. The fights and comments have drained me; I have experienced the anxiety of being the target of online campaigns, of receiving death and rape threats because my politics didn’t match those of the male gaze’s. I know for a fact that my existence online as a woman is not as easy as expected, just as it would be if I were out in the streets. Unable to freely express myself online, I now have no desire to walk down the streets. In spite of my feminism, the chains of looking appropriate and embellishing our politics to cater for others restrained me online; I did not break free from the rules because I know the cost of doing so. What the TikTok women are doing spontaneously, while disregarding the consequences, opens the door for us women to a new space of expression. They did not sign up for the responsibility of “liberating” anyone, but the spontaneity, enjoyment, and humor of their videos liberate me. They help me see a feminist internet, a patriarchy-free street, and spaces where we can be entirely present, without hiding or disguise.

Their freedom is my freedom.

- 1. [1] The Fairmont rape case reflects other class-related factors we need to take into consideration when analyzing the different forms of violence exerted on women in Egypt. Despite their larger margin of freedom, the resistance of women from middle and upper classes to sexual violence is complicated by the status of men in their social classes and their connections to state and authority. While women from upper social classes are not systematically subjected to the harassment, other women from middle and lower classes face it daily on the streets and public commutes. The status of men (harassers and rapists) and the accompanying social privileges, influence, and power complicate their legal accountability and help them get away with it. The Fairmontcase is an extension of what the TikTok women went through (turning the victim into a suspect, as was the case of Menna Abdelaziz, in addition to releasing information with the purpose of defaming the victim/survivor and witnesses). The coercion and violence exerted on The TikTok women, who come from more vulnerable social backgrounds, lay the foundation for a more violent reality that extends beyond the category “woman.”