Performing the “Arab”

This text is based on a presentation given in 2014 at Fem Fresh event at Queen Mary University in London where I was invited as a guest speaker on Live Art and Feminism.

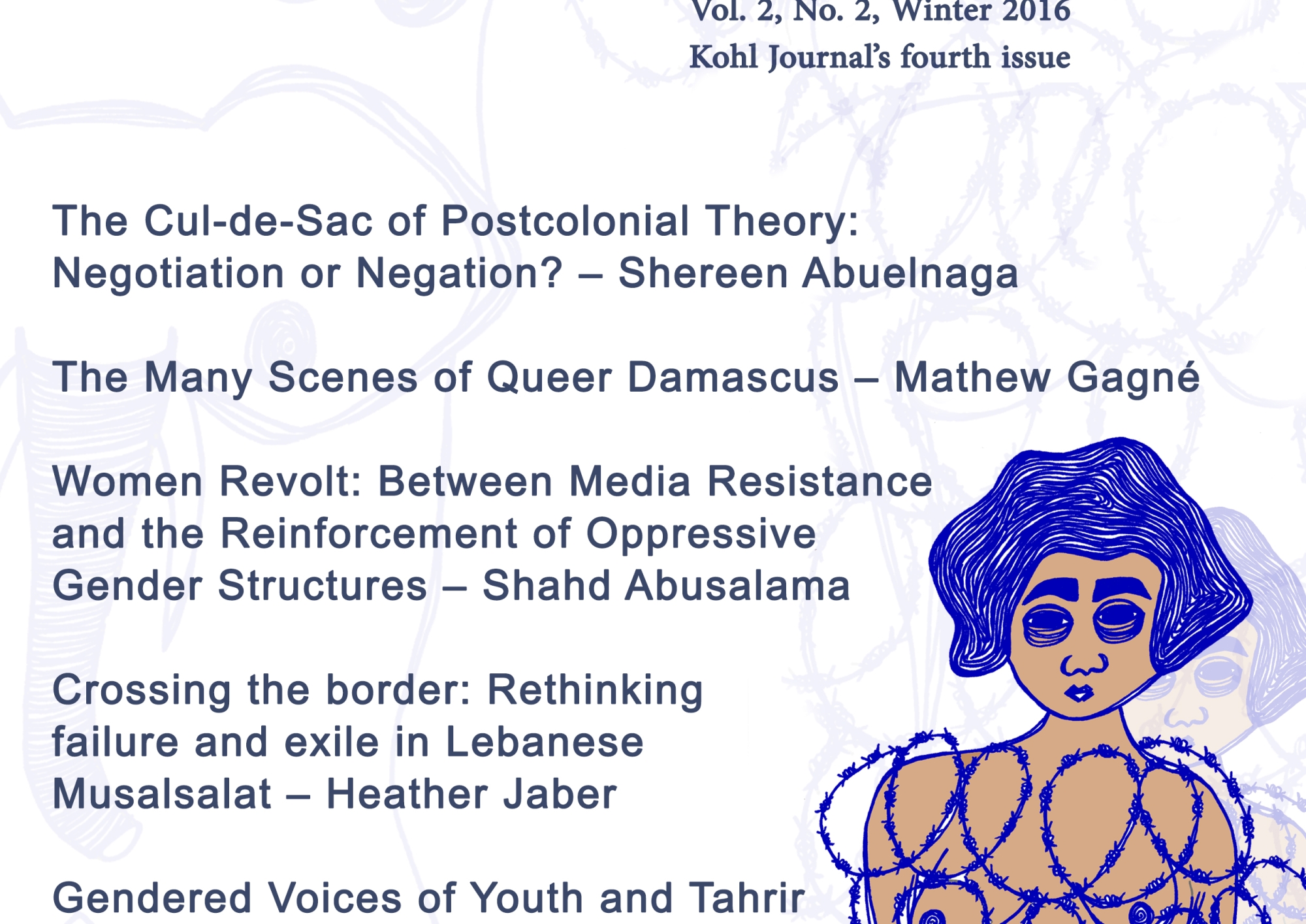

cover_en_2.2.jpg

During the wave of uprisings that swept through the regions of the Middle East and North Africa, thousands of activists – many women among them – were detained, imprisoned, tortured in Bahrain, Egypt, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen, and beyond.

Women in Egypt were present in great numbers in the public demonstrations of the Egyptian revolution of 2011. They affirmed their visibility despite the beatings, gang rapes, and the military-administered virginity tests. In one particularly infamous moment, a soldier dragged a woman on the floor, revealing the blue bra she was wearing before he and his colleagues proceeded to stomp on her. Quickly after that theatrical act of oppression and repression, many deployed the blue bra as a feminist symbol of resistance to both authoritarianism and patriarchy. The image appeared graffitied on walls of various Arab cities.

Women were leading protests in Bahrain. There, the regime detained and arrested their husbands in the hopes of silencing and reigning in the wives that were at the forefront of the movement. One friend of mine, Nazeeha Saed, was arrested and tortured. At one point in this ordeal, authorities shoved her shoe down her throat in an attempt to literally silence her while punishing her for being outspoken. Her voice became much louder after that incident.

In the midst of stories of feminist resistance and revolution emerged FEMEN, a group of topless white female activists who decided to wage war to save brown women from brown men. FEMEN borrows much from Performance Art aesthetics. Some would actually call them a performance movement, as they use nudism, body paint, theatrical movement, symbolic props, and their voices with the aim of shocking the public and forcing those around them into a political discussion. Recently, a young woman filmmaker named Kitty Green 1 documenting the group revealed that FEMEN activists are actually led by what she described as an “abusive man.” Victor Svyatski reportedly runs the show and plays the role of a metteur en scène, choreographing the women’s actions and personally handpicking the most attractive women for the movement. Apparently, he thought that having “beautiful” bare breasts (according to heteropatriarchal standards) would make the political slogan written under them more likely to be picked up by mainstream media.

It seems that the group who wants to save brown women sadly needs saving themselves. As scholar Lila Abu-Lughod has argued, focusing on “saving” Muslim women is very much about saving westerners from confronting their involvement in creating the situation in which these “other” women live, as well as assessing the situation of violence and oppression of women in the west, through creating “a polarization that places feminism only on the side of the West.” 2

As a result of this map of political dissent on the one hand and appropriation on the other, I recently revisited my positionality as a feminist Arab artist working and touring in different places around the world. I recalled the various responses of participating audiences in my interactive performances as well as the responses of passers-by, the police, the media, and my colleagues. I could not help but notice how they varied and how revealing they are of audiences’ own politics.

In 2009, I created a performance called Jarideh, which takes place in public cafés and invites the participating audience to identify the most suspicious person in the café according to the criteria listed in a metropolitan police awareness report. This document had been circulated to the managers of the service sector business in London’s West End in an effort to educate them on how to spot a terrorist. The piece comments on the idea of being able to recognize a terrorist in the public space through recounting the stories of Lebanese female resistance fighters who looked like eighties rock stars, all the while planning military operations as well as hiding guns under their skirt and bombs in their cars. Needless to say, many audience members thought the stories about these secular and cool-looking female freedom fighters were fiction.

In 2011, I created a one-on-one performance called Maybe If You Choreograph Me, You Will Feel Better. This piece was uniquely performed for male audience members. The idea was that I give a man the perfect scene of a woman passing by on the street. The male audience member watches me from a window on the third floor and choreographs me in the city. He speaks to me through wireless headphones and gives me instructions about what to do in the street.

After the audience chose a name a certain walk for me, he was given the choice of costume inspired by two real-life characters: the iconic Palestinian militant Leila Khaled and the queen of Jordan, Rania. We joke about the fact that I am unable to look anything but exotic. In reality, the choice between these two “styles” is very informative. It is not just a choice between a wig and short dress or a Palestinian Kuffieh. It is not just whether my audience leans more towards the Palestinian liberation movement or the western-backed authoritarian regimes of the Middle East. It is also about what they perceive the role of women to be in politics, a female fighter or a propaganda tool of a male monarch.

Some said they chose Queen Rania because Leila Khaled’s photo scares them. Her eyes are fierce, some would say. I still remember someone telling me that she looks like she knows what she wants, which apparently is something he did not feel comfortable with. Needless to say, many men used the term “weak” when they chose adjectives that would describe the woman they were creating: weak, romantic, sad, sexy, and so on.

Upon realizing that the character they created was doing exactly what they were asking me to do, the audience would then ask me to touch myself, punch the pavement, run into the wall, jump in front of a moving car, sob, cry, and shout. I got to a point where I resented performing this piece. It was always tiring, sometimes traumatizing, and most of the time just depressing. But it was a choice, an experiment, a comment on a few things and I cannot say that I was surprised by the fact that men abused the power that was granted to them. But even the men who claimed to be in solidarity as self-identifying feminists or queers would be just as abusive in the show.

But beyond the audience, I was, in many instances, hurt by the responses to the piece coming from colleagues, fellow feminists, most of whom were women who had heard about the idea of the show but could not experience it since it was only for men. These responses were along the lines of: “Great idea Tania. I suppose it’s about where you’re from as it’s a bit crazy there for women, right? Like can you wear what you want there?” Sometimes, this type of commentary was followed by: “I know that because I went on holiday to an Arab country last year.” As if the 22 so-called “Arab” states, with their varying demographics, ethnicities and religions, cultures, histories, and political regimes have a single unified way of treating women. It felt like I was faced with the burden of representing millions of Arab women in that half an hour one-on-one piece, and any conversation I had about the piece.

However complex the ideas that the performance may be addressing, it is often reduced to a simple stereotyped relationship in which the brown woman is the ultimate victim. But there is no such lack of nuance and complexity in the criticism around the work of Western female artists. In that sense, Tracy Emin’s early autobiographical work is discussed in terms of form and content, but rarely if ever is it reduced to a representation of all white women. For example, no one would experience her work and conclude that all British women were raped in their childhood. Yet, invariably, my show must be about Arab women, all Arab women.

Forcing the burden of representation on artists of colour might end up pushing them outside the framework of transnational feminist alliances, locking me into both a sweeping generalization and an Orientalist view of Arab women. Doing so ignores the rise of colonial feminist discourse and the use of brown women’s rights to justify multiple forms of violence on certain non-Western communities. This is indeed the case in the justifications for the war in Afghanistan, that of the repression of migrant minorities in Europe (as in the case of the veil law in France), or to put a fancy, cultured, radical hat on Islamophobia (such as the actions of FEMEN and the DV8 performance Can We Talk About This? at the National Theatre in London).

Looking away from institutionalised Live Art, I am interested in learning from feminist performative politics that continue to happen in public spaces around the world and see how these actions, made by non-artists, inform our work as feminist artists. For example, The Freedom Riders in Palestine attempted to ride Israeli-only buses, drawing inspiration from the original Freedom Riders movement in the racially segregated US. There is also the very theatrical Women In Black anti-war protests and the various protests in cities around the world.

Scholars, activists, and artists are more and more referring to the movement as “multiple feminisms.” That is not “a unitary phenomenon.” Quoting Angela Davis, “the kind of feminism I identify with is a method for research but also for activism.” 3 An uncompromising and urgent activism is indeed needed because as we speak here today, some of us are still detained and tortured for simple acts of feminist performances.