Queering the UK’s Suicide by Ethnicity Statistics

moon_website.png

Sarah Al-Sarraj - Moon

With the advent of the UK’s first suicide statistics to be disaggregated by ethnicity in 2021, the reporting of some gendered and racialised populations as dying at high rates of suicide, marks a shift from the distractory politics of the (white) male suicide crisis wherein (white) men are constructed as victims of suicide (Jordan and Chandler 2019; Helman et al. 2024). How should we receive and respond to this novel suicide data? As evidence of unliveability under white supremacy? As a call to action to expand the cis white maleness of UK suicide knowledge and prevention (Yue 2025)? In this issue of Queer Futures, Kohl “consider[s] queer futures to be both a practice, a method, and a way of doing/being.” Drawing on Kevin Guyan’s concept of queer data literacy, I present a few ways of reading the UK’s first suicide by ethnicity statistics, with the aim of disrupting the technical status quo of statistical knowledge on suicide, informing their use for world-making beyond reproducing the systems that predict and sustain our unliveability. I will begin by introducing the concept of queer data literacy, before outlining some different readings of the UK’s suicide by ethnicity statistics. I hope that my reading(s) will be useful for those interested in doing suicide research as anti-racist work.

Queer Data Literacy

Drawing on data feminism (D’Ignazio and Klein 2020) and the calls of disability rights activists for “Nothing about us without us,” Kevin Guyan introduces the concept of queer data literacy to highlight the power imbalances structuring the collection and analysis of data that impacts LGBTQ lives, with decisions about queer data overwhelmingly gatekept by a cis, heterosexual majority. For Guyan, queer data competence “provides a bare minimum approach to follow for those who make decisions about data that impacts LGBTQ people” (2022:156). Firstly, it “requires a basic knowledge of language and concepts associated with LGTBQ identities, an understanding… [of] historical and social factors…, an awareness of power differences between and within LGBTQ communities, and the intersection of LGBTQ identities with other identity characteristics. Secondly, queer data competence necessitates a willingness to assume a contrarian role in data discussions: present provocations, challenge categories and recognize different ways of knowing” (ibid.). This contrarian role is necessary given the primacy and assumed neutrality of quantitative data in the (suicide) knowledge economy, despite evidence of its racist designs (Benjamin 2019). In what follows, I take up these elements of queer data competence to present provocations to, and different ways of knowing, the UK’s suicide by ethnicity statistics.

(Mis)presenting the Technological Status Quo

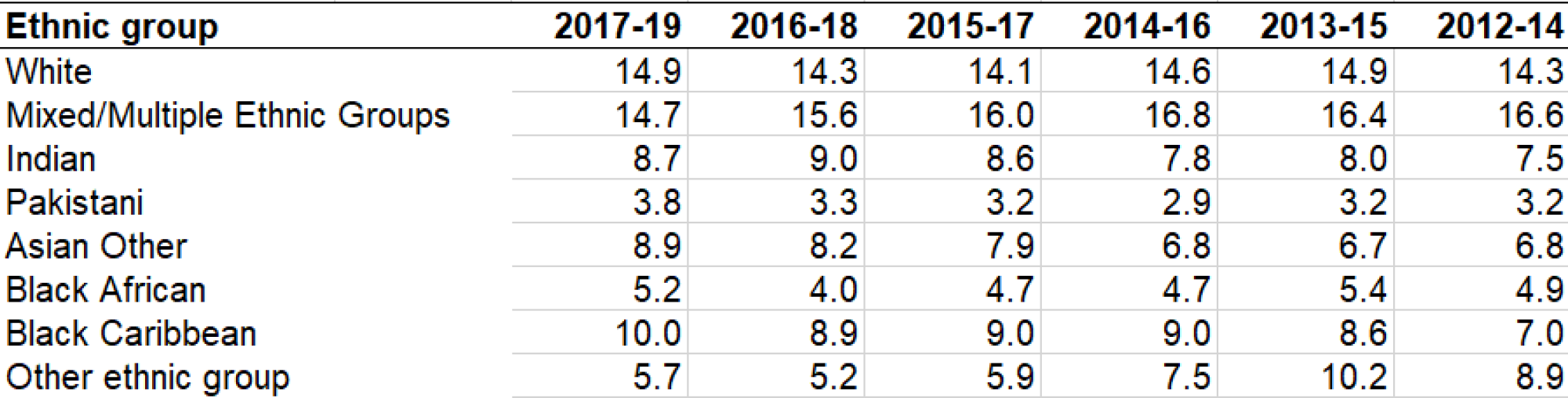

Historically, the UK has reported death, including suicide, based on the axes of age and sex, as it appears on death certificates. In 2021, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) used the National Health Service (NHS) numbers to link death certificates with self-reported ethnicity data in the 2011 Census, in order to produce mortality statistics by ethnicity between 2012-19. The ONS reports White and Mixed/Multiple Ethnic males as dying at the highest rates of suicide. However, this refers to the 2017-19 period only (14.9 White males per 100,000 and 14.8 Mixed males per 100,000). This headline has been taken up by UK suicide prevention charity Samaritans, who suggest “These findings echo other research… [that] found that the highest rate of suicide was among white patients” (2022:1-2).

To see the full data set (for 2012-2019) requires taking an extra step:

When looking at the downloaded table (see below) presenting the full data set, it is only the 2017-19 period that White and Mixed men are reported to die at similarly high rates; in all other reporting periods (between 2012-18), Mixed men died at higher rates. This is not written anywhere on the ONS report.

My intention here is to draw attention to how the presentation of the ONS data – without further inspection – reproduces the construction of suicide as a (white) male problem. This limits the potential of the UK’s first ever suicide by ethnicity statistics to contribute to suicide knowledge and prevention in a meaningful way, such as evidencing the need for anti-racist work not only in the production of suicide inequalities, but in the construction of suicide knowledge (who and what counts as suicide/al).

Data for Inaction

Kevin Guyan (2022) has noted how small numbers of LGBTQ people in datasets, given their minoritised status relative to whole populations, can lead to not using LGBTQ data, or using the data to deprioritise the needs of LGBTQ people. In a similar vein, the ONS reporting Mixed/Multiple ethnic men as dying at similarly high rates of suicide to White men, underrepresents the high rates of suicide reported for Mixed populations. For example, in their “Ethnicity and Suicide” policy position, Samaritans choose not to focus on the mixed populations reported to be dying at the highest rates of suicide; instead they suggest that ethnic minorities in general (including non-mixed ethnic minority groups, with lower reported rates of suicide, and white ethnic minority groups) are dying at different rates of suicide (2022:2), and that we need more research to inform suicide prevention for ethnic minorities (2022:7). Samaritans’ call for “better recording, collection, and communication of the [suicide by ethnicity] data… [for] a complete picture of suicide across ethnic groups” (ibid.) includes some important considerations, such as recording ethnicity on death certificates, and stopping the amalgamation of ethnicity categories (such as the merging of White Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller populations under the White category). Nevertheless, the perception of limited data underrepresents the novel reporting of mixed men and women as dying at disproportionately high rates of suicide, and the potential of unsettling the white maleness of existing suicide reporting and prevention. As Guyan notes, “LGBTQ rights organizations are required to engage with existing systems of power and ways of working to bring about change” (2022:168). Samaritans moving the goalpost for suicide by ethnicity data to the unattainable ideal of “a complete picture of suicide across ethnic groups” (2022:7), reproduces the ever-expanding need for more evidence of uneven possibilities for living under white supremacy, ultimately legitimising the status quo of (white) male suicide prevention.

Scavenging

In her piece “in defence of what’s there,” Sophie Marie Niang (2024) articulates scavenging as a methodology of refusal – a refusal of the colonial logics that render marginalised bodies illegible and require them to make themselves intelligible for extraction, again and again (Campt 2019; see also McKittrick 2020). In 2024, Duleeka Knipe and colleagues used the Office for National Statistics 2012–19 mortality data to calculate the age-standardised suicide rates by sex for each of the 18 self-identified ethnicity groups in England and Wales. In light of Samaritans’ call for more evidence highlighted above, I consider Knipe et al’s (2024) disaggregating work as scavenging – a queer methodology.

Rather than reproducing the homogenising of ethnicity categories (such as White and Mixed), Knipe et al.’s intersectional approach significantly improves the evidence base for ethnicity and suicide in the UK, departing from existing suicide knowledge in a number of ways.

First, in Western countries, women’s suicide/ality has historically been deprioritised based on lower rates of suicide death compared to males (Jaworski 2014; Townsend 2025). Knipe et al. report Mixed White and Caribbean females as dying at higher rates than White British females, with White Gypsy or Irish Traveller females dying at rates more than double that of the White female majority. In addition, while “more males than females died by suicide overall… this difference varied by ethnic group” (2024:614). For example, there was “no variation between males and females” identifying as Arab (2024:615).1

Second, the recording of age and sex on death certificates has spectacularised a crisis of suicide among working-aged men in the UK, generally understood to be white (Wyllie et al. 2012). Disaggregating suicide by age, sex, and ethnicity, Knipe et al.’s data complicates this crisis, reporting high rates of suicide not only among White British working-aged males, but also White Gypsy or Irish Traveller working-age males, and “working age females from a Mixed White and Caribbean background” (2024:615). This has significant implications for the capitalist logics of UK suicide prevention.

Researchers/therapists Tisha X and marcela polanco (2021) highlight the attachment of “euro”suicide2 knowledge and prevention to capitalist logics. Knipe et al.’s (2024) queer use of the ONS data – both for reporting high rates of suicide among some women, and in exceeding the white maleness of the working-aged suicidal subject – holds much potential to highlight and unsettle the UK’s attachment to a white male suicidal subject. Indeed, the focus of much suicide prevention on returning this subject to paid work excludes genderered and racialised populations from this scarce imagining of liveability (whose subjugated labour is required for the able-bodied white male worker ideal). Furthermore, by using what was already publicly available, Knipe et al. (2024) queer and disrupt the endless requirement for more research and evidence on suicide inequalities, while prevention imperatives stay the same. As such, the use of queer methods here reveals the futility of attempts to ‘include’ gendered and racialised populations into existing approaches to suicide prevention that is designed on and for a white male “norm” (Yue 2024). In queering this largely unquestioned preventionist goal in response to suicide (Tack 2019; Baril 2023), the distractory politics of male suicide crisis are exposed in their complicity in reproducing the heteropatriarchal norms and inequalities of an increasingly blatant racist political landscape. It is this landscape that incites anxieties about non-white futures, especially evident in critiques of feminism in male suicide prevention (see Jordan and Chandler 2019) and problematisations of abortion and queer female relationships.

Queer Futuring

I want to end by recognising the inadequacy of suicide data in relation to gender and sexuality. For example we do not have suicide data beyond a male/female binary, with biological sex reported on death certificates used for the production of the ONS suicide statistics. “Small numbers” (Guyan 2022:120) or “statistical invisibility” (Marzetti et al. 2023:1565) have the potential for inaction (prioritising the need for quantification over action), but an increased visibility can also mean increased danger (which for gender non-conforming populations often invites further violence). Nevertheless, Guyan is hopeful for the long-term benefits of visibility: “being counted… can inform how governments and organizations allocate resources and provide services” (2022:169). In relation to suicide and prevention, there is a lack of official data on LGBTQ suicide in the UK, given that neither “sexual orientation, trans identity, nor gender identity are collected when recording death” (Marzetti et al. 2023:1559-1560). Bottom-up organising and scavenging from queer data around the world (e.g. WHO 2014) has nevertheless produced a body of evidence estimating high rates of suicide/ality among LGBTQ populations compared to cisgender heterosexual counterparts (Marzetti et al. 2024). While conceptualising LGBTQ folks as “at risk” of suicide can be pathologising, and doesn’t necessarily translate to unsettling existing prevention approaches (Marzetti et al. 2023), we can understand this approach – practiced outside of the “official” production of evidence on suicide in the ONS suicide statistics – as an example of the use of data for queer futures. LGBT+ early career researchers and their allies (Marzetti et al. 2024) are drawing on this unofficial evidence to co-develop holistic approaches to LGBT+ suicide prevention. By doing so, they invite world-building rather than limiting responses to high rates of suicide/ality, to the prevention of death.

Conclusion

This short piece is designed to be accessible for those interested in engaging data literacy in anti-racist approaches to suicide research. Statistical evidence in the (suicide) knowledge economy has historically privileged (white) men, reported to die at the highest rates.3 I hope to evidence the potentials of the UK’s first ever suicide by ethnicity statistics for expanding the white maleness of UK suicide knowledge and prevention, given the reporting of high rates of suicide among some gendered and racialised populations. However, I have also pointed to the limits of who is visible in the UK’s latest suicide statistics, and highlighted the dangers of reading the statistics in ways that reproduce the technological status quo of UK suicide knowledge. In the context of ever more evidence of suicide inequalities, I have demonstrated ways that some populations have used queer approaches to data to resist their unintelligibility in UK suicide statistics. They are also building more just responses to suicide/ality and uneven possibilities for living, beyond the prevention of (white male) death.

- 1. Importantly, Knipe et al. highlight an “elevated risk of suicide in descendants of migrants (ie, second-generation migrants” (2024:612), e.g. Arab populations here should not necessarily be understood as migrants.

- 2. Highlighting the specificity of globalised medicalised suicide knowledge and prevention as originating from a white European male subject.

- 3. Compared to (white) women, before the disaggregation of suicide by ethnicity in 2021.

Baril, A. (2023). Undoing Suicidism: A Trans, Queer, Crip Approach to Rethinking (Assisted) Suicide. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Campt, T. M. (2019). Black visuality and the practice of refusal. Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, 29(1), 79–87.

D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2020). Data Feminism. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Guyan, K. (2022). Queer Data: Using Gender, Sex and Sexuality Data for Action. London: Bloomsbury.

Helman, R., Huque, S. I., & Chandler, A. (2024). Jarring Encounters: Discomfort, Disruption, and Dominant Narratives of Suicide. Qualitative Health Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323241302653

Jaworski, K. (2014). The Gender of Suicide: Knowledge Production, Theory and Suicidology. Surrey: Ashgate.

Jordan, A., & Chandler, A. (2019). Crisis, what crisis? A feminist analysis of discourse on masculinities and suicide. Journal of Gender Studies, 28(4), 462–474.

Knipe, D., Moran, P., Howe, L. D., Karlsen, S., Kapur, N., Revie, L., & John, A. (2024). Ethnicity and suicide in England and Wales: a national linked cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 11(8), 611–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(24)00184-6

McKittrick, K. (2020). Dear Science and Other Stories. Durham: Duke University Press.

Marzetti, H., Chandler, A., Jordan, A., & Oaten, A. (2023). The politics of LGBT+ suicide and suicide prevention in the UK: risk, responsibility and rhetoric. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 25(11), 1559–1576. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2023.2172614

Marzetti, H., Cooper, C., Mason, A., van Eijk, N. L., Gunn III, J., Kavalidou, K., Zortea, T. C., & Nielsen, E. (2024). LGBTQ+ Suicide – A Call to Action for Researchers and Governments on the Politics, Practices, and Possibilities of LGBTQ+ Suicide Prevention. Crisis, 45(2), 87–92. https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/epdf/10.1027/0227-5910/a000950

Niang, S. M. (2024). in defence of what’s there: notes on scavenging as methodology. Feminist Review, 136(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/01417789231222606

ONS. (2021). Mortality from Leading Causes of Death by Ethnic Group, England and Wales. Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/mortalityfromleadingcausesofdeathbyethnicgroupenglandandwales/2012to2019

Samaritans. (2022). Samaritans Policy Position: Ethnicity and Suicide. https://media.samaritans.org/documents/Ethnicity_and_suicide_July_2022.pdf

Tack, S. (2019). The Logic of Life: Thinking Suicide through Somatechnics. Australian Feminist Studies, 34(99), 46–59.

Townsend, H. (2025). “Drama queens” and “attention seekers”: Characterizations of Femininity and Responses to Women Who Communicated their Intent to Suicide. Gender & Society, 39(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432241300619

WHO (World Health Organisation). (2014). Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564779

Wyllie, C., Platt, S., Brownlie, J., Chandler, A., Connolly, S., Evans, R., & Kennelly, B. (2012). Men, Suicide and Society. Samaritans. https://media.samaritans.org/documents/men-suicide-society-samaritans-2012.pdf

Yue, E. (2025). Ethnicity Statistics as Tricky Tools in “Post-Racial” Britain: Celebrating the Lives and Obscuring the Deaths of Mixed-Race Populations. Catalyst: feminism, theory, technoscience, 11(1), 1–26. https://catalystjournal.org/index.php/catalyst/article/view/39502/33733

Yue, E. (2024). Mixedness and Suicide/ality: Exploring Knowledges of Un/Liveability in Postcolonial Britain. The University of Edinburgh. https://era.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/42624/YueE_2024.pdf