What Does the Future Look Like? A Note to Accompany Visuals

seed_website_sarah.png

Two hands are raised in the air, holding a makeshift slingshot fashioned from an old pair of handcuffs. Pulling the elastic taut, we see dozens of blighty coloured seeds mid-flight.

Three years ago, I spent a somewhat significant amount of time thinking about the visual design for this issue. As deadlines stretched further away, I struggled to find aesthetic markers that could represent a futurity based on the liberation of globally oppressed people. Futurity is so often visually encoded with colonial notions of advancement and progress. And to represent a queer future, when the aesthetics of mainstream queerness reproduce a violent liberalism, feels in conflict.

I wondered whether it was possible to depict a future that holds radical values with the familiar problems of representation and the tendency of our neoliberal moment to assimilate once-radical aesthetics – and render them meaningless. Where is the line between a solarpunk utopia and a greenwashed corporate marketing campaign?

This reminds me of why various Islamic theologians have understood representational images as idolatrous. In Sufism and Surrealism, Adonis writes that “the image is a reflection in one form or another, of a reality that has a prior existence. It is an ‘imitation’” (2016:243-248). The Latin root of the word “image” is imago, meaning “likeness” or “copy.”

A lot of people assign the work of futuring to the imagination. Imagination also stems from the root imago. Robin D.G. Kelley, in his book Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, writes that “without new visions, we don’t know what to build, only what to knock down” (2003:xii). This makes sense – if we do not want to reproduce the violent conditions of the present, we need to exercise our ability to think beyond it.

But how can we do this when our imagination is limited to all we know, have seen, have experienced? I ask this as someone born and raised in the imperial core, the nucleus of colonial power, the birthplace of structural racism – the United Kingdom. The often-cited Fredric Jameson quote, reprised by Mark Fisher as “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism,” is a testament to the importance of this task.

Two years ago, I was visiting Babylon with my family. We went to Saddam’s old palace, the inside looted barren with graffiti covering every ornate wall. I was still pondering the visual aesthetic of this issue. I took out my phone and wrote, “the people, having dismantled the palace, collect the bricks to build their homes.” When I returned to the UK, I typed “parliament in rubble” into Midjourney, an AI imaging software. Unsurprisingly, it could not complete my request, presumably due to algorithmic bias and no existent visual data. I was left to my imagination.

al-sarraj_1.png

Saddam Hussein’s former palace. Personal photograph, 2023.

Mainstream science fiction often depicts the future as a continuation of Western colonial hegemony. Popular sci-fi films such as Minority Report, where police use psychological technology to arrest citizens before they have committed a crime, have inspired counterterror strategies across the Western world.

al-sarraj_2.jpg

Call it a plastic bag*?

In contrast to the notion of the future as a teleological destination, we might understand time as a series of cycles, much like in the natural world. Moments that hold windows into alternate worlds.

al-sarraj_3.png

Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, “Le 30 juin 1960, Zaïre indépendant,” c. 1970–73, acrylic on flour sack. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond © Estate of Tshibumba Kanda Matulu.

This work depicts the speech made by the first Congolese Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, during Independence Day. In response to the Belgian king, who warned to not “compromise the future with hasty reforms,” Lumumba reprimanded the king, plainly stating the violence inflicted on the Congolese people under Belgian colonial rule.

The very same notions of progress that were foundational to the language of settler colonialism, and that promise to accelerate our world into an ecocidal capitalist oblivion today, also constructed indigenous peoples as retrograde and belonging to the past.

Palestinian ecologist and researcher Omar Tesdell draws lessons from agrarian history, stating that seeds and root stock embody historic legacy and future potential. Highlighting the importance of ancestral wisdom, his concept of remnant agroecology explains that cultures come and go, leaving remnants. As we have no way of knowing what will become a useful remnant in the future, being known and recognisable becomes necessary. He edits Barari Flora,1 an online platform for plants in Palestine and the Levant. The seed and the archive can both be considered a technology of the future.

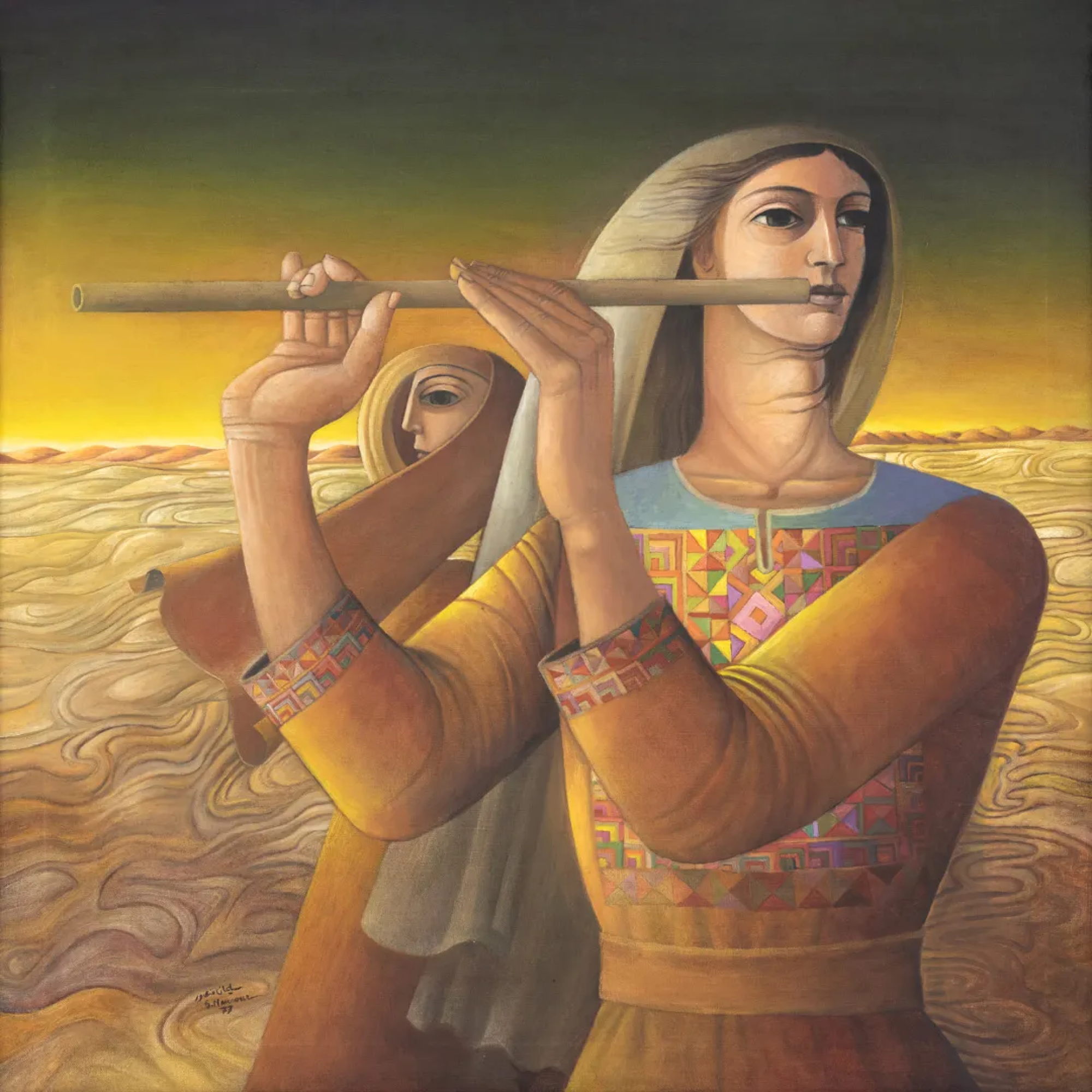

The ancestral also implies survival. I think of Sliman Mansour’s work, his paintings replete with symbols of Palestinian cultural identity and liberation. Often celebrated for his depiction of heritage, many of his paintings bare to me the undeniable visual language of the future.

al-sarraj_4.png

Sliman Mansour ©, “Desert Tunes,” 1977.

In “Suture Fragmentations” (2020), Sarona Abuaker writes that “Return is inherently an experiment in phenomenology; to go or come back is a beckoning of how to arrive.” Since October 2023, many Palestinian authors have also oriented themselves towards queering return through phenomenology. In “The Principle of Return” (2024), Adam HajYahia further theorises that “return produces possibility and fractures the apparatus that polices our imagination and our life. It is the opening to the future as endless uncaptured time.”

al-sarraj_5.png

Shadi Alzaqzouq, “Underground Evolution,” 2015.

The past 2 years have seen unprecedented political action in the UK. We have seen Palestine Action shut down numerous Israeli arms factories. Their resultant proscription under UK terror laws has resulted in mass arrests of the British public opposing complicity in the Israeli genocide in Palestine.

al-sarraj_6.png

Jonathan Y. Eden for Disabled And Here, “Group Sleepover,” 2021. Disabled And Here is a disability-led stock image and interview series celebrating disabled Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC). https://affecttheverb.com/disabledandhere/

Return, then, is not a thing that will occur in the future, or a departure point, but an “activator for aesthetic production as it reflects the conditions of exile” (Abuaker, 2020) and a process occurring in the present moment in order to enable a future (HajYahia, 2024). In such a way, we can consider practices of prefiguration – the act of willfully living the reality you are actively calling in, as a practice of futuring.

In an old iteration of this note, I wrote:

If we are to make this new place into a home, we need models of support that are incompatible with the structures that currently order and govern our lives, structures of racial capitalism and white supremacy, structures of interconnected economic, carceral and ecological violence. We need a kitchen, a bed, a garden, we need someone to do the cooking, we need to borrow and lend money, we need your sofa, we need to call in sick to take a shift waiting outside the police station, and we need relationships of resilience and accountability that are not necessarily based on having the same sense of humour and also some that are, because we need laughter. We need to ask the ones who have the most time to read through all the FOIs.

As we continue to witness mass killing and the erasure of ways of living, knowledge and beliefs, our queer futures require a rupturing of the present, or “a portal” as Arundhati Roy designated the Covid-19 pandemic – the opportunity “to break with the past and imagine the world anew” (2020).

Abuaker, Sarona. 2020. “Suture Fragmentations – A Note on Return.” Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, 6(3). https://kohljournal.press/suture-fragmentations

Adonis. 2016. Sufism and Surrealism. London: Saqi Books.

HajYahia, Adam. 2024. “The Principle of Return: The repressed ruptures of Zionist time.” Parapraxis Magazine. https://www.parapraxismagazine.com/articles/the-principle-of-return

Kelley, Robin D.G. 2003. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Boston: Beacon Press.

Roy, Arundhati. 2020, Apr 3. “The Pandemic is a Portal.” Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca