Zionism in Disarray: An Interrupted Continuum

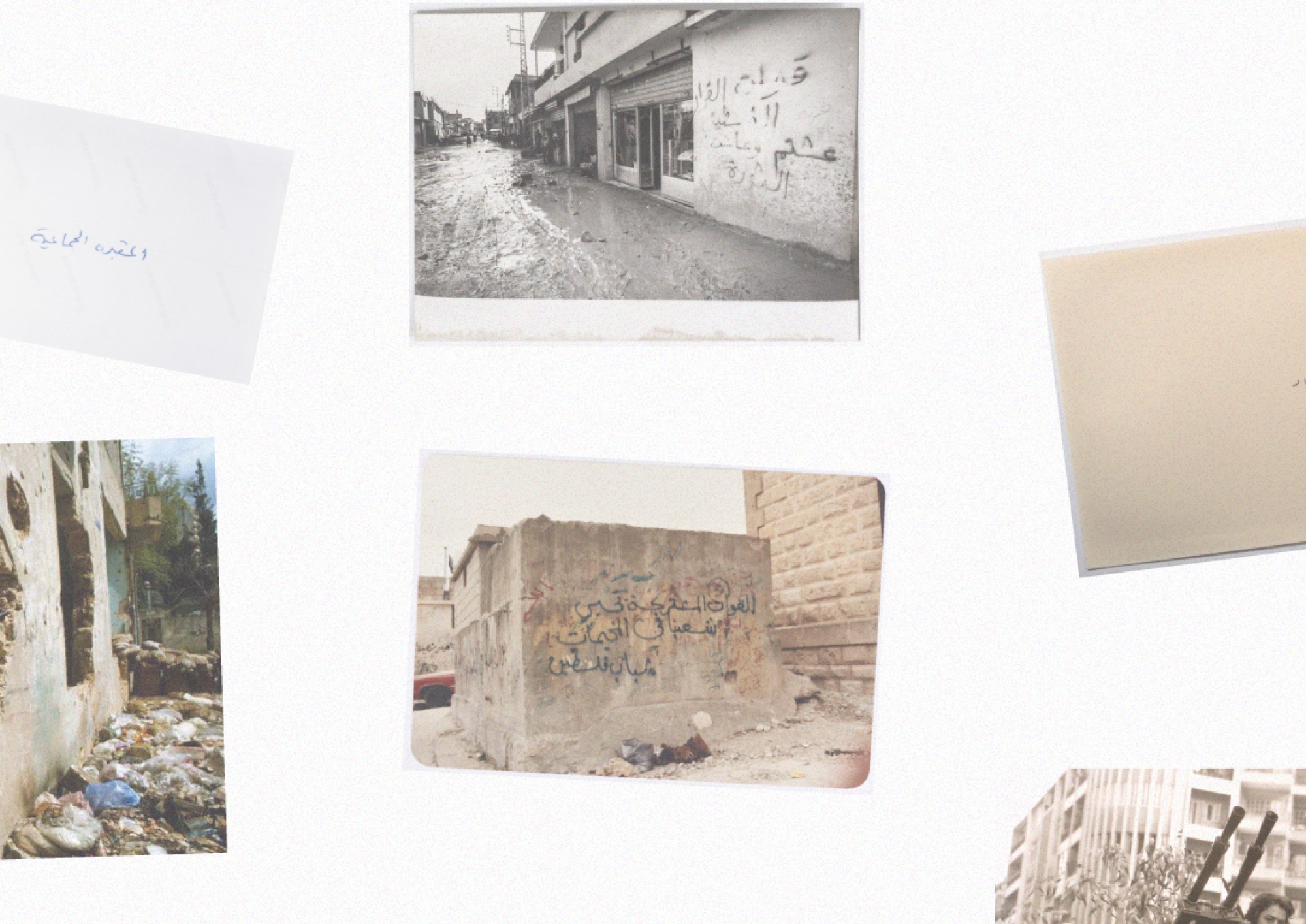

palestinians-and-lebanon.jpg

Note: This article was originally written during Operation Breaking the Wave (also referred to as Break Water) in 2022–2023. Its central aim was to trace the trajectory of military escalations undertaken by the 37th government of the Israeli nation-state, and to analyze a set of discursive encounters surrounding two significant actions carried out by non-factional Palestinian resistance groups in the West Bank.

The article remained unpublished for various reasons – among them, financial and administrative obstacles, as well as the collective paralysis and upheaval triggered by what has since become the horrifying answer to the very questions this article sought to pose: the industrialized eliminations unfolding against the organized sum of Palestinians in Gaza and the West bank.

We regrettably move, as ever, according to a rhythm imposed upon us by our enemies. And yet, as the organized Palestinian people and their societal enclaves continue to remind us, “We will stay here. What other choice do we have?” Perhaps the wave our enemies attempted to break might still carry forward – if not through sustained, coherent analysis, then through the fragmented, interrupted thinking made possible within the constraints of liberalism and war. It is precisely these shifting conditions – of possibility and impossibility – that may explain why the wave, for now, is so easily broken.

Introduction

The fifth Prime Minister of Israel’s government reiterated, when leading the 2023 genocidal operation, what David Ben Gurion had already said in 1955: “Israel is a country with an army, not an army with a country” (as cited in Shlaim 2000:112). This citation is akin to an Israeli monologue – a prologue perhaps. Is Israel fundamentally a military apparatus masquerading as a nation, or a post-colonial state struggling to reconcile its founding contradictions? This tension animates the central problematic of this article: that Israel’s dual identity as both persecutor and mirror weaponizes its trauma to justify expansion while reflecting the global forces (neoliberalism, racial capitalism, imperial patronage) that regulate settler-colonial projects. To reduce Israel to an “enemy” is to misunderstand its function; it is, rather, a laboratory of a contemporary neoliberal, AI-driven, early-stage settler colonialism, where tactics of elimination (Wolfe 2006), gendered nationalism (Shohat 1988), and neoliberal dispossession (Gordon 2018) are perfected. Only by dissecting this complexity can we dismantle its logic and our structural complicity in its regeneration, consequently understanding our failure to resist from where we stand – on the opposite bank of the military operation.

This article will not attempt to answer the pivotal question from which it emerges and to which it gestures – namely, the fundamental nature of the Israeli state. Rather, it will explore the structural intricacies of what is too often reduced to a singular enemy. What I aim to revisit is the narrative of a settler-colonial becoming, situated in dialogue with its own ideological pillars, its preceding ideological regimes (namely, the European metropole), and its internal contradictions and paradoxes. War is, after all, a narrative of geography in motion; the more expansionist a state’s political ambitions becomes, the more isolationist and exclusionary its society tends to grow. Apartheid, as Evans (1997) argues, is both a bureaucratic doctrine and a societal doxa. In this context, the founding of the state of Israel in 1948 signaled a profound turning point: the kibbutz was effectively dethroned from its position as the self-proclaimed socialist vanguard of the envisioned Jewish society. By this, I mean that its once-crucial national functions (pioneering land settlement, populating remote frontiers, spearheading agricultural development, and contributions to national defense) were largely, though not wholly, subsumed by the emerging state apparatus.

The year 1967 marked the dawn of a new socio-legal regime, especially in the administration of the West Bank – an era that demanded a retooled mechanism for settler-colonial expansion. Enter the modernized kibbutz, rebranded as the “settlement,” or more precisely as international law designates it, the “illegal settlement.” The once-revered kibbutznik, cast in the heroic mold of the halutzim (the Jewish migrant pioneer) was now recast as the Israeli citizen. Yet, beneath this semantic shift lies a critical geo-colonial distinction: the divide between citizen and settler-citizen persists, not merely as a label but as a deeply functional – and strategic – difference in the architecture of occupation.

These transformations – of land, citizenship, and identity – are ongoing, interwoven, and mutually reinforcing, though far from linear. They anchor Israel in a temporal paradox: one that simultaneously reaches back before 1948, especially in relation to the West Bank’s geography, and contradicts it outright. While the state presents itself as a modern, industrialized, religious nation – post-kibbutz and firmly within its internationally recognized borders, it also enacts a project rooted in pre-state logics of conquest and settlement. Social and gender roles, shaped as much by ideology as by necessity, drift between these temporalities and traverse the fragmented, contested geographies they produce.

The “kibbutz industrial revolution” (Fogiel-Bijaoui 2007) of the 1970s reconfigured the figure of the woman-settler. This gender-colonial subject navigated a dual struggle: attempting to reclaim traditional (Jewish) roles as mothers and wives on the one hand, and seeking access to newly emerging educational and labor opportunities on the other. I propose to name this process a gender-colonial transition, a key moment in the class(ed) transformation from agricultural colonizer to middle-class colonial actor.

The gendered division of labor fuels the economic transformation necessary for the emergence of a modern middle class – what might be called the modern citizen. Yet, this gendered-class evolution unfolds unevenly, shaped by a non-linear logic. As the nation-state takes form, it deploys stratification mechanisms that assign differentiated roles to distinct population segments – groups whose functions are determined by their geographic placement within the colonial state’s architecture. In doing so, it simultaneously entrenches a white supremacist logic and enacts demographic “transfer.” Even as kibbutzim and settlements preserve their expansionist mandates, the state’s modernization proceeds along an institutional-military axis – an infrastructure engineered to sustain a perpetually stratified social order. What began as a crude transfer – from agrarian outposts to urban hubs, from “illegal” to “legal” settlements – is reconfigured into the hierarchical schema of the modern nation-state: a metropole model, in which power radiates outward but never evenly.

In this framework, the once-stable binary of Jewish versus non-Jewish can no longer bear the weight of national cohesion. Unity, such as it is, now depends on a far more intricate lattice of identities, roles, and most importantly exclusions. Consequently, the settlers and the settlements take on a temporality that is complementary to, yet differentiated from, the institutional timeline. In other words, two contradictory versions of temporality can exist – but not necessarily coexist – in a singular present through a geography that is sharded by utilitarian delineations of militarization.

For the purposes of this paper, I will focus on the recent (mid-2022) security escalations impacting Israel’s ideological trajectory within the context of the ongoing demonstrations in both Israel and the West Bank. To this end, I aim to trace the linguistic construction of war as a continuum within a settler-colonial framework, highlighting its persistent instrumentalization in producing a binary of strength and vulnerability, often imbued with interchangeable gendered undertones. In order to do so within the scope of an article, I will focus on the discourse analysis of a single event that happened in the Jordan valley on the 7th of April 2022.

War as a continuum: militarization and militarized consciousness

Let me begin with something you already know – something etched into the architecture of every modern empire: Israel is not an anomaly. It is not outside the logic of the metropole, but rather its intimate echo, unfolding in real time. What sets it apart is not exceptionality, but simultaneity – the way it breathes two temporalities at once. It lives in the now and in the before, in the promise of modernity and the persistence of conquest. In this duality, Israel becomes a living text, an explanatory model of the metamorphoses colonial powers underwent in the early twentieth century, as they draped continuity in the illusion of rupture and called it “post-colonial.”

But this simultaneity is also its curse, laid bare by the unwavering, defiant resistance of the Palestinian people – a resistance so rooted, so gallantly unyielding, that it exposes the illusion, uncloaks the masquerade, and reminds the world that no state can fully sever its present from the violence of its origin. Militarization and militancy are, at their core, products of the same industrial complex; they hold a dialectical relationship, each reaffirming and reshaping the other. Yet, they diverge in the discourse of war and conflict, especially when viewed through the lenses of class, affect, and socioeconomic structure. The gendering of securitized identities, like that of the settler, roots militancy in the domestic sphere, embedding it in the very processes that produce and sustain gendered familial roles.

To examine the meaning of gender within a functionally militarized society is, in effect, to trace the shifting objectives of militancy in relation to the larger project of the nation-state. Militarization is not merely an instrument of defense; it is an industrial logic of the state itself, one that inscribes a moral and value system into the subject formed under institutional power. In this way, militarization and the nation-state are existentially co-constituted. It is also a market logic, a structural condition of state budgeting that reaches beyond military expenditure to shape the very contours of life for all communities under state control. This includes, but is not limited to, the nation proper. Militarization mediates the relationship between the nation and its technologies, informing tactical and strategic choices that increasingly permeate civilian life. In every case – whether during war, undeclared war (what is often called “peace” 1), or internal unrest brought on by political, environmental, or biological crises – the aim of militarization remains the same: to manage, contain, and discipline populations.

The target of all militarization (and ultimately the tool to safeguard it) is the constellation of differentiated and different identities and class positions that mark the dialogue between the societal consciousness (plural) and the super-structure of the state, or in Marxist terms, the bourgeois-will of the state. Those identities are channeled and remolded in favor of the institutional character of their military positioning. This is core to our argumentation about gender as a tool to remold the consciousness of a presumed post-Zionist citizen, subservient to the institution of the sovereign Israeli state. In light of the above, militancy’s function is to serve as an infra-state ideological habituation of the militarized character of its society. On militancy as a pillar to the kibbutz, Agassi (1989) shows that the gendered character of the settlement is regenerated in neoliberal times. This continuous regeneration emanates from war for the purpose of reengineering its features, agents, and subjects (i.e., its subsequent relationalities), and is precisely what the feminist legacy calls the war continuum.

According to Cynthia Cockburn (2004), the war continuum includes not only direct acts of violence such as combat and bombing, but also the broader social, economic, and political structures and structuring that support and perpetuate militarism. In settler-colonial contexts, the continuum of war and peace takes on a heightened complexity, whereby the modern nation-state aligns itself with sweeping societal reconfigurations, forged through the twin engines of settlement expansion and military occupation. These forces, while interdependent, often operate in tension, appearing both complementary and mutually exclusive. This dynamic recalls Cockburn’s assertion that war should not be understood as a binary opposition to peace, but rather as a continuum – a fluid sequence of overlapping and interwoven stages. Within this framework, war becomes the instrument through which the state regulates and stabilizes social transformation, particularly at those historical junctures when national reordering is ideologically desired and strategically pursued by the state’s governing superstructure. Blowing the horns of war – like the ancient shofar echoing through the empires’ bloody history – may either be an accelerationist or a decelerationist act, marking not redemption but recalibration.

In the geography of historic Palestine, particularly within the borders of “Mandate” Palestine, militarization does not follow a linear trajectory. Agrarian genocidal violence operates both within and beyond the temporality of the nation-state, and the pre-institutional industrialization of agrarian life forms the bedrock of militancy as doxa – as common sense. It is precisely here that settler consciousness is forged. As an apparatus that outsources and extends the army’s expansionist reach, the settlement manufactures the identity of the “heroic” citizen – a transformation of the Jew from Untermensch to Übermensch (Mayer 2000). But this heroic image is scaffolded atop the labor of hyper-surveilled, hyper-documented, and systematically disenfranchised Palestinian workers, who sustain the markets of an ascendant neoliberal order. This utilitarian relationship to the colonized reveals that “neo-Zionism” is less a rupture than a rhetorical sleight of hand – a means to rationalize the shift from kibbutz to nation-state, from settler to citizen, from agrarian genocide to the urban annihilation of the colonized.

Military escalation, then, is not merely a matter of air raids or artillery. It is inscribed into the mundane: in the daily circulations across the West Bank, in the liminal choreography around Gaza’s borderlands, in the theatrical violence of the checkpoint and the regulated movement of labor. Each act accumulates toward a war of erasure that is partial or total, but always possible. There is no post-war moment in this landscape – no clean demilitarization. Militancy and militarization are temporally entangled, always overlapping in the settler-colonial condition. Ironically, it is in moments of de-escalated war – those quiet intervals – that the settler’s social fabric begins to fray. For in the absence of open conflict, the settler community turns inward, absorbed in its market logic and demographic anxieties (racial and functional i.e. settler/citizen), revealing the deep instability of its own project.

“Citizenship” in Israel, then, assumes a fragile and anxious character: an imagined community tethered in oneness to the institution of coercion itself.

The scene

The West Bank’s most politically troubling refugee camp, Jenin, has been the site of constant confrontation against the Israeli army since the First Intifada. The significance of the camp could be said to lie in its organized frameworks of resistance, which have withstood the test of neoliberalizing the occupied territories. Indeed, neither the Israeli army nor the Palestinian authorities’ security apparatus managed to liquidate them.

From January to April 2023, the Israeli army conducted several “security” operations in the West Bank that consisted in assassinating a number of young Palestinian militant leaders and Palestinians with no affiliations (80 people were killed in the course of 3 months), demolishing their families’ houses and hunting down their relatives in coordination with the Palestinian Preventive Security (PPS). At the same time, massive Israeli citizen crowds2 marched in opposition to the Israeli government’s efforts to limit the power of the Supreme Court. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his right-wing and religious allies sought to pass legislation that would give lawmakers more influence over judicial appointments, and restrict the Supreme Court’s authority to rule against the legislature and executive. Netanyahu’s current administration, formed in December 2022 with ultra-Orthodox and far-right parties, places great importance on judicial reform.3

The Huwara checkpoint, located in the north of the West Bank and south of Nablus, is a significant Israeli military installation situated along Route 60, a key artery connecting Palestinian cities and towns. Established as part of Israel’s broader network of checkpoints in the occupied West Bank, the Huwara checkpoint primarily regulates the movement of Palestinian workers, creating a bottleneck that disproportionately impacts the indigenous working class. Since its implementation, the checkpoint has become a focal point of surveillance and control, employing advanced technologies, including IT and artificial intelligence (AI), to monitor and restrict the movement of Palestinians. This system of surveillance extends beyond immediate security concerns, functioning as a mechanism of systemic control over the Palestinian population, and particularly targeting the working class who rely on daily passage for employment and livelihood. The checkpoint, like others in the West Bank, serves as a tool of apartheid-style governance, reinforcing spatial segregation, economic dependency, and the broader infrastructure of the Israeli occupation.

The checkpoint’s impact is felt acutely by residents of nearby Palestinian refugee camps, including Balata, Askar, and Ein Beit al-Ma’, all located within a 5- to 8-kilometer radius of Huwara. Established in 1950, these camps are home to refugees displaced during the 1948 Nakba and their descendants, many of whom depend on movement through the checkpoint for access to work, education, and healthcare. The Huwara checkpoint thus exemplifies the intersection of military control, technological surveillance, and the socio-economic stratification inherent in the Israeli apartheid system, while also highlighting the layered security-economic coercion of Palestinian refugee communities under military occupation.

In my sense, Huwara represents the dramatic culmination of a discursive struggle in which competing political institutions, while ostensibly striving toward a vision of “post-coloniality”4 to finalize a post-Zionist era of the nation-state, continue to sustain fundamental settler-colonial practices. This ideological contestation has extended to the highest echelons of Israel’s primary imperial ally, the United States, and has become a site of negotiation between international powers, the Israeli government, and its opposition. At its core, this struggle is structured around a dichotomy of shame and morality, particularly as it pertains to the opposing roles of the Israeli settler as a political and ideological figure vs. the military as an institution of legal enforcement. This process of dichotomization is instrumentalized through Israel’s ideological framework and imposed onto its structurally adaptive mechanisms of expulsion, displacement, resettlement, securitization, and biopolitical control. The settler communities and the state’s military apparatus constitute the two primary “bodies” through which this binary is enacted and reified. The ways in which these dichotomies are reaffirmed or contested within the quotidian discourse of Israeli communities necessitate a gendered analytical lens, which will be explored in the following section.

Gendering the plot: a discursive shift

On February 26, 2023, two Israeli settlers were killed in a shooting attack near the Palestinian town of Huwara. Reports indicate that their car was fired upon on Route 60, following a collision with another vehicle. A few weeks later, on April 7, a similar attack occurred in the Jordan Valley, where two more Israeli settlers were killed under comparable circumstances: gunfire following a vehicular collision. In both cases, the pattern of attack remained consistent, highlighting the intensifying dynamics of resistance within the occupied territories.

Following the April 7 incident, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu delivered an hour-long press conference, extending condolences to the victims’ families while simultaneously embedding their grief within a broader geopolitical narrative that served to justify Israel’s ongoing policies of occupation and repression. He framed the attack as part of an existential struggle, linking it to what he termed Iranian aggression, Hamas “terrorism,” and the alleged “threat” posed by the indigenous Palestinian population – both inside Israel and in the occupied West Bank. Notably, this framing was selectively applied; the April 7 incident was officially designated a “terrorist attack” against the Israeli state, while the February 26 attack was not, revealing the instrumentalization of such incidents to reinforce particular gendered colonial narratives and entrench systems of control.

The settlers killed on February 26 were two brothers; those killed on April 7 were two sisters. In the case of the April 7 assassination, the textual coverage of the BBC, CNN, and Haaretz – the three media outlets I am analyzing – focused on the gender of the settlers, and did not consider their identity as settlers in the headline. Haaretz reported “Two Israeli-British Sisters Killed” as a headline on April 7,5 and “two Israelis were shot dead in Hawara” in the subheading on February 27.6 As for the BBC, its headline reported “Two British-Israeli women killed in West Bank shooting” on April 7,7 as opposed to the CNN reporting “Two Israeli settlers killed in West Bank shooting” on February 26.8

A headline addresses a framework of consciousness that exists or that is intended to be in the making. Not only were those “victims” women in international discourse, they were presented as elements of a family unit (sisters) in the local Israeli discourse, and a vessel of the nation’s reproduction. The killing called for a local response, intimate to the community they belonged to, compounded with a national response. In other words, it was necessary, as shown in the Haaretz coverage, to quote the police commissioner of the settlement who called on “every citizen who possesses a licensed weapon and is skilled in operating it legally to carry it.”9 This particularly and visibly gendered settler is also a hyphenated nation-state identity – a reminder of the Alya (or the Jewish migrations to historical Palestine in the first half of the 19th century) and of the international nature of the geopolitics at hand (British-Israeli). It is also one that calls the entirety of the nation’s military apparatus to be mobilized for their rescue. On the other hand, the killing of the two brothers needed not fixate on any gendered dynamic (even in the context of the gendered adjectives in the modern Hebrew language); the appeal to the family was not discursively necessary. The official condolences called for “revenge” as a chain reaction differentiated from the apparatus of sovereignty (the army), and according to Haaretz, “Bezalel Smotrich called on his ‘fellow settler brothers’ to resist taking the law into their own hands.”10 This discrepancy is also apparent in CNN’s coverage: on the April 7 assassination, they quoted Netanyahu who “instructed Israeli police ‘to mobilize all border police units in reserve and the IDF.”11 On the February 26 assassination, they reported that the Regional Council would “embrace the family and […] be with them as much as necessary.”12 Therefore, it can be concluded that a settler “man” is a militant function; a settler “woman” is a state of collective emergency that calls for the conscientious paradigm of restoration, recovery, remembrance, and overall alert to be put in motion.

In times of war, the disruption of familial structures necessitates the emergence of alternative kinship networks, as the foundational roles of the family (caregiving, socialization, and economic support) are destabilized. Within the context of Israel’s settler-colonial project, this phenomenon is particularly evident in the fracturing of the agrarian/industrial securitized military family, a structure that has historically underpinned Zionist settler identity. Ann Laura Stoler’s (2002) analysis of colonial regimes demonstrates how the regulation of intimate spaces functions as a mechanism of power, a dynamic that is clearly observable in Israel’s governance of Palestinian life. Women often occupy a central role in the reconstruction of social and communal networks, taking on responsibilities as caregivers, mediators, and stabilizing agents who work to sustain their communities amidst conditions of displacement, violence, and systemic rupture. This reconfiguration of kinship structures, as explored by Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian (2009) in the Palestinian context, not only reveals the fragility of settler-colonial identities but also underscores the resilience of those who resist their imposed logic.

The destabilization of the agrarian/industrial securitized military family within Israel’s settler-colonial framework can be further analyzed through Shafir’s (1989) examination of labor and land acquisition as foundational elements of early Zionist settler identity. This identity, as Zertal and Eldar (2007) argue, remains deeply intertwined with the settlement movement and its role in shaping Israeli national narratives. However, as Rouhana (1997) contends, the contradictions within this identity become increasingly visible under the conditions of war and occupation, exposing the inherent tensions in Israel’s colonial project. Veracini’s (2010) theoretical framework of settler colonialism further illustrates how the maintenance of settler dominance is contingent upon the regulation of intimate spaces, including the family. Meanwhile, Weizman’s (2017) analysis of the spatial dimensions of occupation demonstrates how settlers and the Israeli state utilize architecture and infrastructure to enforce their control; yet, paradoxically, these very structures become sites of contestation and resistance, not of Palestinians solely but of the settlers against the reshaping of hegemony led by the state.

The primary division within Israel today is not merely ideological but spatial: it lies between the urban citizen and the settler – those residing in so-called “illegal” settlements and kibbutzim positioned along the fault lines of occupation. The urban citizen embodies the future of the nation-state, reaping the benefits of security ensured by the military apparatus, internal policing, and the settler-created buffer zones. The settler, by contrast, represents a past forged in close proximity to resistance, territorial friction, and the daily realities of indigenous opposition. This past is not passive memory but a lived condition. Settlers and kibbutzniks near Palestinian towns, ghettos, and cities inhabit zones of intensified contact, where the nation’s most enduring contradictions are not theorized, but experienced. Here, the Israeli working class, particularly in its (re)productive dimensions, occupies a liminal position, straddling the line between modern Israel and what might be called “indigenous colonial terror.” It is precisely this liminality that enables a conditional alliance between the urban citizen and the settler.

The settler functions as a buffer, both physical and ideological, insulating the urban centers from the friction and eruptions of Palestinian resistance. At the same time, the settler remains dependent on the legitimacy, resources, and symbolic affirmation provided by the state and its urban population. This is a mutual dependency disguised as ideological divergence – a structural interlock that sustains both identities. This alliance is not merely strategic; it is affective. It is reinforced by trans-provincial solidarities that rely on mutual emotional and logistical support in the face of perceived existential threat. Such experiences blur geographic and ideological lines, forming a collective national project that binds citizen and settler under the banner of a shared homeland.

At the heart of this project stands the Israeli working class, whose reproductive and productive bodies are tasked with mediating the past and the present, the frontier and the city. It is through this class that the state imagines a bridge between settler and citizen, between the periphery and the metropole. To maintain coherence amid these contradictions, the state must engineer a new kind of unity – a rehomogenization that reconciles the settler’s historical condition with the citizen’s modern aspirations. This process, metaphorically and materially, becomes an act of “cleansing the home” (beit). Far from symbolic, this act of revision addresses the deeply embedded tensions between kinship, territory, and security. By managing the internal paradoxes of the family-as-nation, the state seeks cohesion in the face of perpetual fragmentation.

Ultimately, the relationship between the settler and the citizen forms a central axis through which the tensions of class, nationalism, and settler colonialism are negotiated. Drawing on Rosenhek and Shalev’s (2013) insights, we see how the Israeli urban working class occupies a paradox: it benefits from state-maintained infrastructures of security and capital, while remaining spatially and psychically removed from the frontlines of conflict. This removal is made possible by the settler, who absorbs the proximity to resistance, displacement, and insurgency. In this framework, the settler is not simply a historical residue but an active condition at the edge of the nation-state’s reach. Meanwhile, the urban citizen, buffered and secured, becomes the inheritor of a national future whose stability depends on a past it refuses to acknowledge, yet sentimentally (national whiff) cannot do without. Wolfe’s (2006) foundational work on settler colonialism deepens this analysis, emphasizing that it is not a singular historical event but an ongoing structure, fundamentally oriented toward the elimination of Indigenous presence and the construction of a new social order. Yet, as Rosenhek and Shalev (2013) remind us, this division is riddled with contradictions: the urban working class remains both complicit in and critical of state policies, caught between the material benefits of security and the moral costs of displacement and exclusion.

Shohat’s (1988) critique of the Israeli concept of home (beit) further complicates this picture. She argues that the state’s narrative of home is intrinsically exclusionary, built upon the displacement of Palestinians and the marginalization of non-European Jewish communities. In this context, the settler emerges as a stark symbol of exclusion, embodying the territorial ambitions of the state. To emancipate the settler from their functionalist militancy – that is, from being reduced to merely a cog in the machinery of state violence and territorial expansion, a particular victimhood is constructed around them. This victim is both gendered and classed, serving as a necessary foil to justify their ongoing role. Importantly, this is no longer about the Jewish crisis of masculinity described by Mayer (2000), which focused on personal or cultural anxieties. Instead, the question has shifted toward national functionality, or how settlers are integrated into national identity through redefined family roles.

To understand this fully, it is crucial to differentiate between various types of settlers in Israeli history, particularly the settler kibbutz resident and others living in settlements with different functions and geographies. The settler kibbutznik, historically rooted in early Zionist socialist ideals, was initially both a pioneer and a militant figure, engaged directly in agrarian labor, land cultivation, and territorial defense on the frontlines. Their identity was closely tied to the collective and ideological mission of building the Jewish nation through physical and political presence in contested lands. Over time, however, as state institutions consolidated power and the nature of settlement changed, these roles diversified and shifted. The settler kibbutz resident became more embedded in state security structures, serving simultaneously as an active agent of control and as a “reserve army” of victims – people whose very existence on the margins legitimizes the state’s military and political agenda. Meanwhile, other settlers, particularly those in officially recognized settlements near Palestinian towns or in more strategic zones, occupy a different functional position: they are less of ideological pioneers and more of extensions of the state’s expansionist policies, living in a space where the settler identity is shaped by proximity to conflict, surveillance, and a tenuous claim to legitimacy. In sum, these differences illustrate how settler identities and functions are not fixed but evolve as a function of time, geography, and shifting state priorities. Understanding these distinctions is key to grasping how settler consciousness is continuously produced, maintained, and transformed in relation to the nation-state and its ongoing territorial and political projects.

Just as in any capitalist-based, post-feudal ideology, the settler family is a pillar of the Zionist project. The particularity of the Zionist context, however, resides in the meaning of the new Jew, made from the trenches of war-torn Europe. The family is where masculinity/femininity is cemented, militarism transformed into a peculiar class consciousness, and the altering meaning of Zionist nationalism shaped. Drawing from a Marxist feminist perspective, Anne McClintock (1995) argues that wars are intimately connected to the construction and reproduction of the nation-state, in the sense that they are often justified as necessary for the defense of the nation, and promote the notions of masculinity, heroism, and sacrifice. In the context of Zionist discourse and militarized nationalism, women are frequently relegated to the roles of passive victims or symbolic supporters of the war effort – positions that ultimately reinforce traditional gender roles and patriarchal structures. However, when women become central to a discourse of victimhood, their representation often functions as a mobilizing mechanism for broader nationalist imperatives. In the Israeli case, the notion of female “defilement” – as Joseph Massad (1995) might describe it – serves as a symbolic indicator that honorable and respectable Israeli citizens, both men and women, must rally to defend their sisters and mothers against two interlinked threats: the figure of the “Arab terrorist” and the internal failures of the state-security apparatus in preventing such violence. This invocation of violated femininity operates not simply as a gendered moral panic but as a political technology of securitization, instrumental in reaffirming state legitimacy and redirecting public attention toward external enemies and internal disorder. Simultaneously, it gestures toward another internal contradiction: the emergence of the figure of the rogue settler.

The settler, in this context, represents not a direct bodily threat – unlike Palestinians, whose mere physical presence is often constructed as existentially threatening unless they are confined to specific roles (e.g. as labor). Instead, the settler embodies a structural anomaly: a residual (and consequently rogue) figure of the state’s expansionist past. The settler operates as a buffer-zone function, symbolizing the unresolved tension between the Zionist project of territorial maximalism and the state’s current desire for consolidation and legitimacy within defined borders. Thus, in the current phase of neo-Zionism, the settler must be transformed from an autonomous actor representing the fusion of militarism and messianism (“the army with the state”), into a disciplined citizen-subject subordinated to the sovereignty of the state and its military apparatus (“a state with an army”). This transformation is not merely rhetorical; it signals a crucial reorientation of Zionist governance, as articulated by Likud leadership, toward the normalization of power within statist and securitarian frameworks.

Eliminating the settler as a functional category (rather than as a body) requires either the completion of the expansionist project or the articulation of a conclusive security doctrine that addresses the ongoing presence of the indigenous remainder. In other words, the colonial state must either fully resolve the territorial question through annexation and demographic engineering, or devise what some officials have ominously framed as a “Final Solution” to the Palestinian presence. As Israeli officials have increasingly implied, this strategic pivot is not only about spatial containment and expansion but about the redefinition of Zionism itself, from a frontier-driven movement to a centralized state power whose legitimacy hinges on its ability to manage, absorb, or eliminate both internal contradictions and external threats.

The senior military official revealed that he favors issuing detention or restraining orders to curb activities of radical settlers. “Radical elements might attempt to disrupt the peace, they might attack Palestinian villages, we have no information of specific attacks, but […] weapons should be taken away from the would-be evacuees […]” the official added.13

This statement illustrates how culture is synonymous with the security/military valuation of bodies, and a product of power relations and securitization norms. It also shows how bodies, in the viewpoint of settler colonial machinery, are functionalist biological entities constructed through the nation state’s language and discourse. Those biological functions change with the geopolitical tides, or with the middle classes altering their bourgeois habits. Echoing Judith Butler (2011), and within the frameworks of Zionist ideology, the value given to a certain body or identity is not natural or inherent to its Jewishness or its antithesis (the Palestinian colonial subject) alone. Rather, this value is produced and reproduced through security practices and discursive formations. Bodies take a certain meaning “within a matrix of power relations” (Butler 2011:2), and are made to lose said meaning if they don’t serve the continuum of the war towards post-Zionism. In other words, certain bodies are considered “valuable” and others, “worthless” (ibid.). I may be repeating myself, but some points deserve insistence: in a capitalist world, as with most things, groups of people are not treated as autonomous subjects but as pragmatic functions, defined by their geo-social, linguistic, and relational positions. Their value is not inherent but contingent, activated when useful and sidelined when not.

The settler exemplifies this logic perfectly. The very neo-Zionist project that now seeks to contain and manage the settler, folding them back into the orderly architecture of the state, will not hesitate to unleash them when strategic conditions shift. The settler is not a static identity but a flexible instrument, one that can be restrained or empowered depending on geopolitical exigencies. For instance, if international allies falter in their support of Israel’s expansionist ambitions – or if Palestinian resistance reaches a new crescendo (or, though more speculative, regional Arab opposition intensifies) – the settler may once again be unleashed as a frontline agent of national survival. The once-“rogue” figure would become re-legitimized, not despite their volatility, but because of it. In the machinery of settler-colonial governance, today’s liability is always just a crisis away from becoming tomorrow’s necessity.

The utility of a gendered settler within a settler colonial scene14

The settler in contemporary neoliberal Israel is no longer romanticized as the halutz (pioneer) of the kibbutz era – a transformation that exposes settler colonialism’s remarkable talent for rebranding itself in sync with shifting economic and geopolitical trends (Wolfe 2006). Gone is the plow-wielding socialist hero; in their place stands the gated-community, mortgage-backed, mall-adjacent entrepreneur. Under Labor Zionism, the kibbutz settler embodied productive colonization – a phase Wolfe might call “settler primitivism,” in which agrarian labor conveniently camouflaged land theft under the warm glow of collective ideals and early morning songs. Today’s neoliberal settler, still heavily subsidized, appears as a market actor: the same logic of elimination now dressed in the language of deregulated real estate and security entrepreneurship.

Geopolitical demands add another layer to this makeover. International pressure divides settlers into rogue elements (like the ever-convenient hilltop youth) and sanctioned ones, such as the residents of the Ariel bloc. It is akin to a Netanyahu casting of villains and heroes in a speech he wrote, directed, then blamed on the audience. This internal differentiation echoes Wolfe’s analysis of how settler societies must eventually disown their more unruly avatars once sufficient territorial dominance has been achieved. Meanwhile, the settler’s utility fluctuates in tandem with Palestinian resistance. Whether faced with armed struggle or BDS campaigns, the state tactically adjusts the settler’s symbolic and material role, reinforcing Wolfe’s (2006) point that settler colonialism survives not by standing still, but by transforming just enough to keep moving.

The settler family, too, is swept up in this transformation. Under Labor Zionism, the kibbutz family was the engine of national reproduction, its gendered structure, especially the image of women as mothers of the nation, fitting neatly with Wolfe’s notion of “generational sovereignty” (2006). Today’s neoliberal settler family performs a different function: it reproduces privatized elimination. Gated communities have replaced collectivist enclaves, and women’s bodies symbolize not collective sacrifice but hyper-individualized resilience—because nothing says national continuity like prenatal yoga in a bulletproof suburb. This neoliberal shift obscures continuity: land is still expropriated, but the ideological packaging has gone from isolationist armed socialist kibbutz to security-oriented condo development. In short, the changing figure of the settler is not a sign of colonialism’s retreat, but its makeover—a fresh coat of paint on Wolfe’s enduring insight that settler colonialism is “a structure, not an event” (2006:388).

Settlers are not just traders, soldiers, or governors; they are a population with an autonomous affectual belonging to a cleansed land. In other words, they claim dominion on certain religious narratives and historical claims that give them a sense of entitlement to the political affairs of the land. Settler colonialism is different from other types of colonialism in that it continues to impose population transfers (displacements and/or genocides) and exerts state sovereignty and legal control over cleansed or coercively emptied territories. Wolfe (2006) challenges the idea that colonialism is simply a relationship between colonizers and colonized. Instead, he contends that colonialism involves the creation of new societies and social structures, which fundamentally transforms the ways in which people understand and relate to one another. In particular, settler colonialism involves the establishment of a new society by settlers who displace or replace the indigenous population through their unity. Reconfiguration, then, might entail a demographic repair through a continuous breakdown of the indigenous administrative and social structures through post-structural colonial strategies. These reconfigurations are anchored in the making of the new Jewish-citizen consciousness, or what Butler (2011), following Michel Foucault, calls regulative discourses, chains of language, and comportment. Over time, these establish scripts for normative behavior as designated by the state.

The binary opposition between “settler” and “native” is a central feature of colonialism and settler colonialism: it naturalizes and legitimizes the colonial project by creating a hierarchy between the settler and native populations. This hierarchy is not just a matter of perception or ideology, but is grounded in material reality. The division of land between settlers and natives is a concrete expression of the settler/native binary – a division that is diluted in the post-expansionist phase. Settler extraction is executed by the institutions of sovereignty rather than discrete heterogeneous communities, and settler societies continue to rely on the settler/native binary to maintain their social and political dominance. This ongoing process of colonialism means that settler societies are constantly re-creating the conditions that allowed them to establish themselves in the first place.

Contrary to popular belief, settler colonial cultures continue to be colonial even when political ties to the original metropole are broken. The reason is that the offshoots of those cultures aim at transforming themselves into metropoles in and of themselves, hence reiterating structures of economic expansionism and nationalist supremacy. In other words, settler colonialism seeks its own abolition: it doesn’t aim to preserve colonial structures and power disparities between colonizers and colonized, but attempts instead to eliminate the challenges posed to settler sovereignty by the claims of indigenous/uprooted peoples’ to land. That happens by eliminating the cultural, political, and legal peculiar status or the existence of indigenous peoples themselves through replacing their political being with constructs of minority-citizenry (i.e. sub-identitarian categorization), and a conditionally invisibilized reserve army of labor. The erasure of the indigenous comes through a symbolic erasure of the idea of their continuum, by ablating their historical identity and reducing it to demographics of recognized and unrecognized labor.15 It is at this pivotal juncture that the components of the state (its institutions of coercion), the settler, and the uprooted population of the colonial project are under reconfiguration, in their relations and representation.

In pursuit of national homogeneity, the settler has to be heavily sexed, and the family revalorized and glorified. This linguistic gendered manipulation reconditions the settler to a militarized masculinity, and sustains the conditions for settler extraction and erasure. In other words, post-Zionism is an attempt to address the conundrum and execute the “final erasure” of the colonized. Conclusively, these societal renewals and the reconstruction of citizen consciousness serves the colonial project as it continues to shape social relations long after the initial period of colonization has ended.

Victimhood Nationalism: the gendered spell of post-Zionism

The struggle to erase settler consciousness within a settler colonial project is also the struggle to build a nationalist imagination that is hyphenated: anchored in national identity while simultaneously dependent on transnational infrastructures of power. Both the Israeli citizen and the settler live a double existence, as national subjects loyal to the state, and as cosmopolitan actors embedded in global systems. This hyphenation is not incidental; it is essential for the survival of the settler colony against the ongoing militant resistance of the indigenous population. For Israel, this tension points toward two possible futures: either the eradication of the unifying antagonist (the Palestinian), or the dismantling of the settler condition itself through the creation of a sovereign Palestinian state. This is why belonging to the state of Israel is marked by a fundamental contradiction: the demand for rooted national belonging collides with the necessity of sustaining a transnational identity. It is within this contradiction that post-Zionism emerges, grappling with the unresolved question of how to mend the split between national loyalty and global dependence.

Post-Zionism does not offer a singular solution to this crisis; instead, it is fragmented into multiple strategies, each attempting to negotiate the contradiction in different ways. Some versions lean toward neoliberal globalization, seeking to dissolve national tensions into market cosmopolitanism. Others turn inward, reimagining Jewish identity through cultural critique or diasporic pluralism, loosening the settler state’s exclusive territorial claims. Yet, each of these strategies remains haunted by the same structural dilemma: how to sustain a national project whose infrastructural and material survival depends precisely on transcending its own nationalist foundations. The settler identity has to be resolved to emancipate the settler colony from its structural nature into the modern nation state. The family is where the imaginary (keeping Anderson’s imagined communities in mind) travels, and the “woman” serves to homogenize the settler society in front of the so-called “hand of terror.” To echo Jie-Hyun Lim’s “victimhood nationalism” (2014), gender is added to the matrix of epistemic consciousness. The modus operandi of victimhood nationalism in Israel shows a linguistic and historical (narrative) consumption of victimhood on a gendered basis. Once the victims are gendered, they become a call for collective union in order to reimagine militarist functionality. The woman victim is the epistemological binary of collective guilt and innocence; she is where Zionism resuscitates victimhood as a historical culture of self-confrontation. She is the family where collective guilt and innocence become a homogeneous entity for the modern post-settler to seep through. Ultimately, the complexity of victimhood nationalism is in direct confrontation with liberation movements, its colonized subject, and the “post-colonial” nation-states surrounding it.

In this article, we examined the nexus between the settler and the citizen. In the forthcoming piece, we will turn our attention to a specific formation of this settler-citizen dynamic: the transnational state in motion – that is, the Israeli diaspora. We will explore its relationship with the indigenous diaspora and the political economy of the war continuum they jointly sustain. This analysis seeks to illuminate a critical frontline of confrontation that, during this genocidal war, we failed to mobilize in our favor – leaving Gaza and the West Bank at the mercy of a singular, asymmetrical battlefield.

- 1. In times when genocidal policies do not make the headlines.

- 2. Thousands of Israelis assembled in central Tel Aviv as part of weekly demonstrations opposing the government's judicial reform proposals, occurring just days ahead of the commencement of a new parliamentary session.

- 3. The bureaucratic conundrum could only be resolved by returning to the kibbutz identity and accelerating the pace of the genocidal continuum, showing once again that socio-political identity and the mechanisms of state-sanctioned violence are intertwined.

- 4. My use of post-colonial in this context/text is not an attempt at describing the present condition of a former colony. Israel is a modern lingering colony; yet, post-Zionism is a discourse that proposes to shed the exclusivist and nationalist ideology of Zionism and to explore a more cosmopolitan and universalistic Israeli identity from the standpoint of a Mosse-ian (1993) nation-state. This discourse falsely sees a perceived shift in the consciousness of a new generation that has learned the lessons of the past and is ready to move “beyond” Zionism. However, this obscures the ongoing reality of Israeli colonialism and occupation, and glosses over the deep-rooted structural issues that perpetuate the conflict. As Noura Erakat (2019) clearly articulates, while post-Zionism is a flawed concept, it is not the focal point of Palestinian critique. The problem is the fundamental and enduring belief in Zionism that it purports to transcend.

- 5. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2023-04-07/ty-article/three-israelis-severely-wounded-in-shooting-attack-in-the-countrys-north/00000187-5ad6-dcdb-a9af-daffbfe40000

- 6. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2023-02-27/ty-article/.premium/israels-ben-gvir-vows-to-crush-enemies-after-settlers-west-bank-revenge-riot/00000186-9262-db08-a986-de76609a0000

- 7. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-65211160

- 8. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/02/26/middleeast/west-bank-violence-intl/index.html#:~:text=The%20shooting%20of%20the%20settlers,at%20least%2011%20Palestinians%20dead

- 9. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2023-04-07/ty-article/three-israelis-severely-wounded-in-shooting-attack-in-the-countrys-north/00000187-5ad6-dcdb-a9af-daffbfe40000

- 10. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2023-02-27/ty-article/.premium/israels-ben-gvir-vows-to-crush-enemies-after-settlers-west-bank-revenge-riot/00000186-9262-db08-a986-de76609a0000

- 11. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/05/04/middleeast/israel-idf-operation-kills-gunman-britain-intl-hnk/index.html

- 12. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/02/26/middleeast/west-bank-violence-intl/index.html#:~:text=The%20shooting%20of%20the%20settlers,at%20least%2011%20Palestinians%20dead

- 13. https://imemc.org/article/10216/

- 14. Jeff Halper (2021) and Ilan Pappé (2008) argue that Israel is a settler colonial state that has sought to erase the indigenous Palestinian presence and establish a new Jewish society on Palestinian land.

- 15. This often takes the form of creating subservient authority structures or fragmenting populations into segregated, depoliticized units. Netanyahu, at times, gestures toward the need for necropolitical and military erasure when these local authorities or security apparatuses, initially intended to manage dissent, begin repositioning themselves as agents of indigenous resistance. In such cases, the occupation effectively outsources its mechanisms of control, only to react violently when those mechanisms turn against it.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1983.

Agassi, Judith Buber. “Theories of Gender Equality: Lessons from the Israeli Kibbutz.” Gender and Society 3, no. 2 (1989): 160–86.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge, 1993 [2011].

Cockburn, Cynthia. “A Continuum of Violence: A Gender Perspective on War and Peace.” In Sites of Violence: Gender and Conflict Zones, edited by Wenona Giles and Jennifer Hyndman, 24–44. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Erakat, Noura. Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press: 2019.

Evans, Ivan. Bureaucracy and Race: Native Administration in South Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Fogiel-Bijaoui, Sylvie. “Women in the Kibbutz: The ‘Mixed Blessing’ of Neo-Liberalism.” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender 13 (2007): 102–22.

Gordon, Todd. “Capitalism, Neoliberalism, and Unfree Labour.” Critical Sociology 45, no. 6 (2018): 921–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920518763936.

Halper, Jeff. Decolonizing Israel, Liberating Palestine: Zionism, Settler Colonialism, and the Case for One Democratic State. London: Pluto Press, 2021.

Lim, Jie-Hyun. “Victimhood Nationalism in the Memory of Mass Dictatorship.” In Mass Dictatorship and Memory as Ever Present Past, edited by Jie-Hyun Lim, Barbara Walker, and Peter Lambert, 33–61. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Massad, Joseph A. “Conceiving the Masculine: Gender and Palestinian Nationalism.” Middle East Journal 49, no. 3 (1995): 467–83.

Mayer, Tamar. “From Zero to Hero: Masculinity in Jewish Nationalism.” In Gender Ironies of Nationalism: Sexing the Nation, 283–308. London and New York: Routledge, 2000.

McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Mosse, George L. Confronting the Nation: Jewish and Western Nationalism. Hanover & London: Brandeis University Press, 1993.

Pappé, Ilan. “Zionism as Colonialism: A Comparative View of Diluted Colonialism in Asia and Africa.” South Atlantic Quarterly 107, no. 4 (2008): 611–633.

Rosenhek, Zeev, and Michael Shalev. “The Political Economy of Israel’s ‘Social Justice’ Protests: A Class and Generational Analysis.” Contemporary Social Science 9, no. 1 (2013): 31–48. https://doi.org/doi:10.1080/21582041.2013.851405.

Rouhana, Nadim. Palestinian Citizens in an Ethnic Jewish State: Identities in Conflict. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Shafir, Gershon. Land, Labor and the Origins of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, 1882-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Nadera. Militarization and Violence against Women in Conflict Zones in the Middle East: A Palestinian Case-Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Shlaim, Avi. The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World. New York: W. W. Norton, 2000.

Shohat, Ella. “Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Jewish Victims.” Social Text, no. 19/20 (1988): 1–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/466176.

Stoler, Ann Laura. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Veracini, Lorenzo. Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010.

Weizman, Eyal. Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. London: Verso, 2017.

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

Zertal, Idith, and Akiva Eldar. Lords of the Land: The War over Israel’s Settlements in the Occupied Territories, 1967-2007. New York: Nation Books, 2007.