Tunnel – I mean, trench!

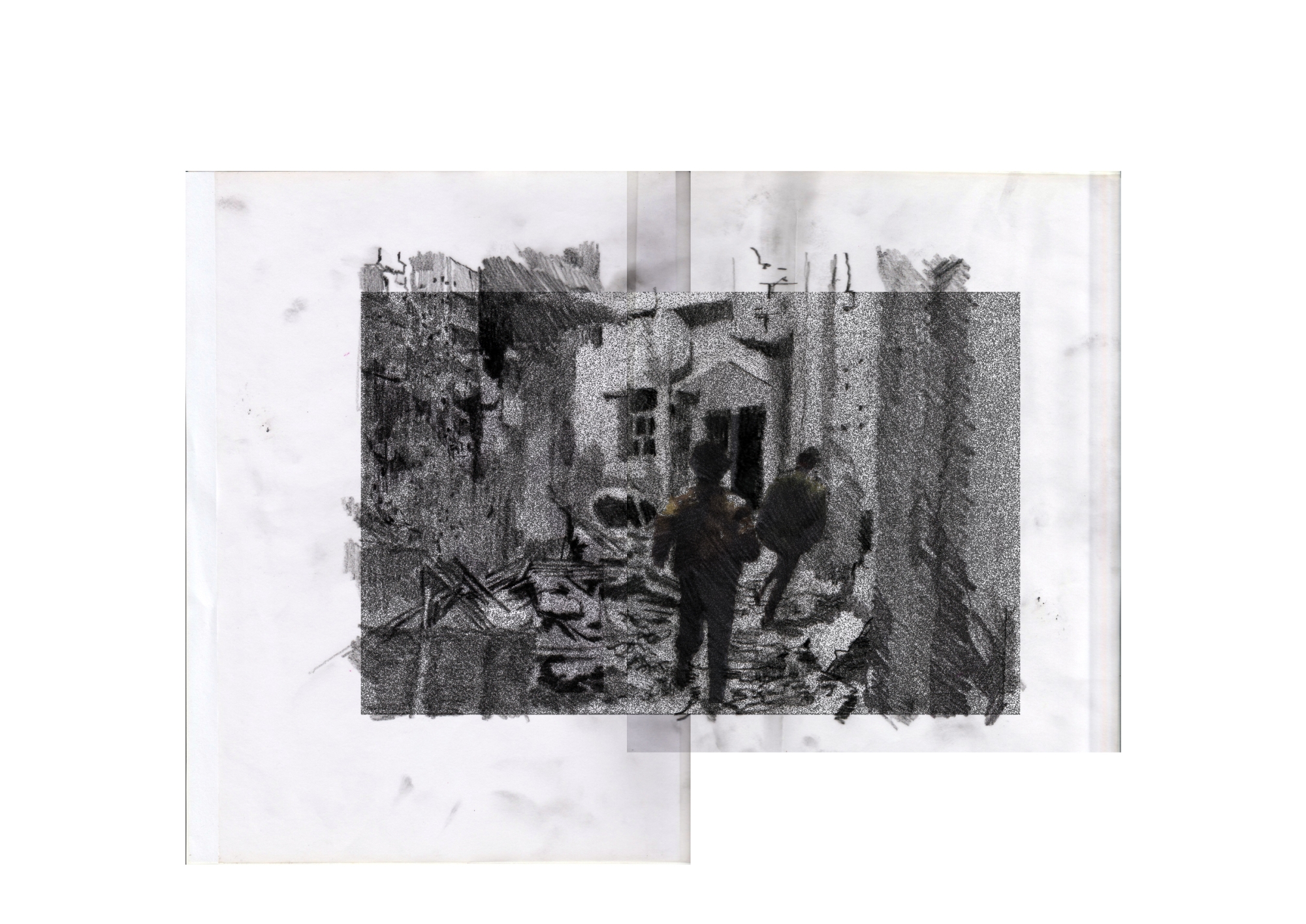

innab-01.jpg

Drawing based on a photo from the personal collection of engineer Hassan Bakir, 2024.

Original image title: Bombing at Shatila Mosque, Hassan Bakir, 1987.

Tunnel – I mean, trench!1

Scene One: A Cautious Attempt at Writing

I will strive to write with a certain level of ambiguity, as a way to reflect on my positionality as an architect and urban researcher within the broader context of knowledge production, and the potential extractivism it may entail.

Around the summer of 2010, I found myself seated with several representatives of various Palestinian factions, gathered for the initial participatory design session of a public building intended for shared use among these groups. In Nahr al-Bared, this process is not unique. Like any other building in Nahr al-Bared, this process requires the architect to meet with key stakeholders, users, and residents, drawn from the local families. The aim is to ensure that essential needs are met, but also to navigate the intricate particularities of life within the camp. Each session unfolds within the tight, suffocating spaces of the camp, compounded by the weight of official constraints and bureaucratic complexities. To accommodate lived realities within rigid, often unforgiving frameworks is a delicate balance.

I attempt to grasp the conversation unfolding among the men about the building in question – let’s call it Building M.A.

Sparks flew moments later, as the conversation subtly alluded to another time, a palimpsest of history of which traces persist. Each time I sought further clarification, the session facilitator grew visibly uneasy, acutely aware of the delicate nature of the discussion. Soon, it became evident that any conversation about redesigning the building had to traverse its complex past – the history of factional disputes, which had imprinted themselves onto the building, entangling it with claims of ownership and legitimacy. Suddenly, the devastation of 1983 surfaced – the year the camp fell after a siege and bombardment by the Syrian regime, following the PLO’s withdrawal from Beirut and Yasser Arafat’s return to northern Lebanon via Cyprus. The internal splits within “Fatah al-Intifada” and the “Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command” were invoked, seamlessly connecting the past destruction to the present (the siege of Tripoli and the ensuing War on the Camps).2

When the Lebanese army leveled Nahr al-Bared camp to the ground in the summer of 2007, hidden bunkers and tunnels – locally dubbed “Abu Ammar’s tunnels” were uncovered following its complete obliteration. The very notion of these tunnels were systematically instrumentalized by the army and the entirety of the Lebanese state agencies, not merely as a propaganda tool but as a weapon to stoke fear among the public and rouse patriotic fervor. It became yet another rallying cry to “reclaim” national sovereignty, a narrative often invoked in times of crisis. But this time, the manipulation of this narrative transcended mere rhetoric; it tightened the grip on the terms of reconstruction – if reconstruction was ever to occur – and deepened the security apparatus governing the site. The camp, now envisioned as a fully militarized model by the authorities, became a testing ground for future security measures. For the state, it was an opportunity to “correct” the status quo, perhaps even laying the groundwork for a new, controlled relationship with the camps, an unspoken desire for transformation cloaked in the guise of national security. The masterplan for the camp was drafted through a collaborative effort between the Nahr al-Bared Reconstruction Committee for Civil Action and Civil Studies, UNRWA,3 and the Lebanese government, which included the Lebanese Army, the Directorate General of Urban Planning , and the Lebanese Palestinian Dialogue Committee, alongside representatives of the PLO. The plan was subjected to an exhaustive series of maneuvers and amendments, passing through more than 200 iterations. In each of these versions, the demands of the Lebanese Army defined the broad lines of the project, which despite their many components can be summarized into an imagined future destruction, an impending invasion, and an unmistakably severed relationship with the land as a living, organic entity. One such demand, for instance, was the prohibition of retaining walls higher than three meters, and most crucially, a ban on the construction of basements. This was despite the desperate need for flexibility given the camp’s limited space, uneven topography, and shifting levels. Additional stipulations dictated the width of certain streets, the length of continuous facades, and even the height of balconies. Each of these requirements had less to do with the practicalities of reconstruction and everything to do with the military’s desire to strip the camp bare – an urban landscape laid open, exposed, and ready for control.

It is essential to clarify that I will not engage in a critique of this specific reconstruction process or its relation to the broader Palestinian context, particularly given the immediate reality of the ongoing devastation in Gaza. I believe that no current intellectual or structural frameworks are capable of fully extricating themselves from the root causes of destruction; even those that seem to resist it in the form continue to replicate it in substance. The issue of reconstruction in contemporary contexts has not been spared from the sweeping neoliberal transformations of the built environment, evident from Sarajevo to Beirut, where similar patterns of devastation and violence have been reproduced. In the Palestinian context, systemic destruction – whether through artillery shelling, missiles, bulldozers, or forcing Palestinians to knock their homes down with their own hands – renders the reconstruction process an inevitable equation, one that simultaneously constitutes an act of daily resistance. Each process has its own questions, and perhaps returning to the basics would be essential if we are to tackle the Palestinian reconstruction outside the borders of Palestine: in this case, how valid is this proposition?

Here, I am speaking specifically of the camp. Since their inception, Palestinian camps have stood in defiance of erasure – whether through Israeli invasions or what international law euphemistically dubs “host states.” This term, laden with a discourse of abstraction as a political instrument, is fraught with implications. It silently enforces “rules of hospitality” upon this so-called “guest,” rules that shift with each host’s whims. Similarly, we see this in the global tendency and preference to address colonialism and its consequences through sterile abstraction in what is now termed “post-colonial” contexts, without any consideration for its manifestations, continuation, or relentless capitalist extraction in the present. This discourse addresses and analyzes colonialism as a closed chapter, by dealing only with the corpses of the colonized, and considers the present the threshold from which the “past” is questioned, assuming this past is not now. Within the same line, both the camp and the refugee are identified and seen in the legal-political frameworks only: as exceptions, as guests who must display an almost sacred politeness; as margins or a mere side effect of “modernity” – but most importantly, as silent objects. Their very power lies in being the well-mannered victim or the inert corpse, and their cause’s legitimacy is made to be contingent upon this perception. An unspoken apology prefaces every action they take – an apology that justifies their every move in advance. This systemic abstraction, and the violence it perpetuates, is not confined to academia or legal frameworks. It seeps into the collective imagination, shaping how societies conceive of their relationships to a multitude of meanings: authority, return, occupation, liberation, armed resistance as an unconditional right, and beyond.

The battles in Nahr al-Bared erupted on May 20, 2007, and raged for over three and a half months, during which the Lebanese army unleashed relentless bombardment on both the old camp and its extension, known as the new camp. The destruction that befell Nahr al-Bared reveals profound layers of separation and isolation, exposing dimensions of division that run far deeper than the physical ruins. In the immediate aftermath of the devastation, what was visible at the time was only the surface of a far-reaching rupture: these so-called “battles” did not truly conclude with their official end in early September 2007. The camp was reduced to rubble and turned into a tightly controlled militarized zone, its entry restricted to those who possessed a permit from army intelligence. Checkpoints sprang up like barriers of containment, encircling the camp and severing its ties to the surrounding region. Four key entry points were established: from the north, the checkpoint at Abdeh; from the east, the one at Mahammara; and from the south, two more – at Bahnin and Shakir Mosque. The old camp became completely off-limits, while access to parts of the new camp was selectively granted to UNRWA delegations (tasked with overseeing reconstruction) and state representatives (including the Khatib & Alami company). For two long years, the residents of Nahr al-Bared were denied entry into the remnants of their homes. When the passages finally creaked open for just a few fleeting hours – before the rubble removal and bulldozers arrived to flatten the land – families rushed back, desperate to salvage whatever they could from the wreckage. But soon after, the camp was leveled to the ground.4

In 2009, a decree was issued announcing the “new official designation” for what was commonly known as the “New Camp,” renaming it “The Adjacent Areas.” The decree was broadcast on local television channels and required all officials involved to use the new title in their official dealings. This renaming is more than just a change in terminology; it reflects the state’s persistent efforts to impose strict demarcations on the camp’s borders, effectively refusing to recognize its expansion. This act represents a separation of the camp from its own physical and spatial extension. This divide was further emphasized by the development of distinct and separate reconstruction plans for the old and new camp, each falling under a different jurisdiction: the old camp remains under the administration of UNRWA, while the new camp is governed by the Lebanese state, as it lies outside the camp’s official borders.

innab-01.jpg

Drawing based on a photo from the personal collection of engineer Hassan Bakir, 2024.

Original image title: Bombing at Shatila Mosque, Hassan Bakir, 1987.

These tunnels in Al-Bared were not an isolated or unique case. Shatila, too, only survived the years of The War on the Camps (1985-1987 حرب المخيمات) thanks to the tunnels dug by its residents – both women and men – to circumvent the siege and “expose” it.

Scene Two: Panic and Urban Legends

In June 2014, the Lebanese public awoke to an image allegedly showing a tunnel connecting the Burj el-Barajneh camp to Sabra – and panic ensued. Whether the photo was real or whether such a tunnel does exist today,5 what stands out is the authorities’ deep-seated obsession with tunnels and with destroying them relentlessly.

The news hardly startled the residents of the camps, for tunnels had long been a crucial element in resisting both the Israeli invasion and the brutalities that took place during the War on the Camps. Beyond makeshift bomb shelters, the exact origins of tunneling and underground refuge in Lebanon’s Palestinian refugee camps remain elusive. Some trace the early efforts to lessons learned from the Vietnamese “Viet Cong” in guerrilla warfare. What is certain, however, is that with the looming threat of anti-camp blockades in the early 1980s, the digging of tunnels became a desperate measure to prevent the starvation witnessed in Tel al-Zaatar from being repeated. In the holy month of Ramadan, 1985, the Amal militia – bolstered by Syrian regime support and aided by the defected Sixth Brigade of the Lebanese army – encircled the camps in Beirut and the south, raining down artillery fire and sniper attacks on the besieged for two and a half relentless years. This siege, coordinated with those who had broken ranks from the Fatah movement, sought to choke the life out of the camps.

In his book on the siege and battles in the Shatila camp in 1986,6 and despite it not being his first time experiencing such circumstances in Beirut or Lebanon, Dr. Chris Giannou offers a harrowing account detailing the all-too-familiar horrors of starvation, siege, and the continuous attempts to erase all forms of life and its structures. What stands out is how the narrative and imagery seem to move through a complex fourth dimension, where testimonies from one time period collide with those from another – like dreaming that you are dreaming, in this case a nightmare within a nightmare. These dimensions become clearer when survivors of the Tel al-Zaatar massacre speak to the author about the “lessons learned” and what should or should not be done, with a beguiling simplicity. In the summer of 1976, right-wing Maronite militias besieged the Tel al-Zaatar camp on the outskirts of East Beirut. “When the camp finally surrendered the International Red Cross organized the evacuation of the inhabitants. The right-wing militias did not respect the Red Cross auspices and massacred the entire adult male population of about 2,500 on the road during evacuation. Their widows had by now grown into middle age, and their children had entered adulthood.”7 Many of these survivors eventually sought refuge in Shatila.

The zones around Tel al-Zaatar were once key industrial hubs in the surrounding areas. By the late 1970s, they accounted for 29% of workshops, 22% of the labor force, and 23% of industrial capital. Economic systems often shape the demographic distribution within cities and their outskirts, and this can be seen in the way urban fabrics develop around industrial centers and factories. In these suburban areas, factories were strategically located to serve as geographical extensions of the city, functioning as economic continuations or even alternatives. These peripheries filled a crucial gap in the economic cycle, as a function of their proximity to the urban core. They provided essential services to industrial enterprises and workshops, offering relatively inexpensive land and labor. To fully grasp the magnitude of the massacre, an understanding of the role of the Lebanese bourgeoisie in the region should be in order, because it is that peculiar role which directly informed their stance on the Palestinian Cause.

Our neighbors were all kinds of people – Palestinians, Lebanese Shi’ites, and Kurds. They were cheap workers for nearby factories. The Phalangists8 besieged us for fifty-four days. We had enough food and weapons. What defeated us, what forced us to surrender, was the water supply. They cut the water pipes, and we had no wells inside Tel el-Zaatar. Snipers killed many women and children who tried to crawl up to the few spigots to fill a jerrycan with water.9

Attempts to find water sources beyond the control of Amal became a lifeline for the camp’s workers and organizers. In the documentary I Was There (produced by Al Araby TV in 2017), women vividly recount their harrowing daily struggles under the siege of Shatila and Burj al-Barajneh. They ventured out in small groups to find food and water to ensure the fighters were fed. They talk of harassment at checkpoints, of sudden sniper fire, and how to maneuver their movement from the camp. But the most important part of their stories was digging the tunnels. These underground passageways were the camp’s secret lifelines, linking isolated neighborhoods and defying a siege that could last up to six months at a time. These women shouldered sacks of rice and groceries and greens; hidden among them were 60mm mortar shells and RPG rounds smuggled from leftist political contacts in West Beirut, supplying the camp with food and ammunition. They also smuggled cement buried in the bags of food supplies, determined to rebuild what had been destroyed. Over three brutal years of war, they rebuilt and restored large parts of the camp not once, but three times.

Given the difficulties in navigating the camp’s alleys and the constant threat posed by snipers, it became essential to devise defensive strategies that would both secure the camp and allow for attacks and safe exits. Tunnels were dug along key axes to serve as defensive lines. As one witness described, “We dig vertically down three or four meters, then crawl horizontally. To reinforce the tunnel roofs, we use doors and window frames salvaged from the rubble of destroyed buildings, along with mortar and wooden planks.”10

As each day of that first week of relentless bombing wore on, less and less of the camp was habitable. The flattened buildings forced the defenders along the perimeter of Shatila to withdraw from position after position, moving closer to the center of the camp. The noose around Shatila was being drawn tighter. Soon, there would be no camp left; not a building would remain standing. Where would the defenders go? What would remain standing. What would they do? How could that continue to defend a mass rubble? […] Along the eastern border of the camp, a couple of men had dug, by the fourth day, a tunnel underneath one of the collapsed buildings, coming to surface beyond in a foxhole amidst the ruins. Ali Abu Toq, with his experience in the People’s Republic of China and Vietnam, was acquainted with the practice of excavating a labyrinth of tunnels. Following the early example of the eastern front, and under Ali’s guidance, the fighters in the camp spent ten days digging by hand with crude trowels and shovels, creating a network of interlocking underground passageways, tunnels, and even entire rooms. They excavated four miles of tunnels around the perimeter of the 200 yards by 200 yards of Shatila. The debris of shattered buildings overhead protected the men underground from any further shelling. […] After an artillery barrage to force back the defenders, the opposing militiamen and soldiers would attempt a frontal assault to occupy the terrain. But the foxhole exists of the tunnels and passages surfaced amidst the broken concrete slabs of collapsed walls, ceilings, and roofs at the original front lines. […] Ali was an engineering genius, and his makeshift techniques using all sorts of everyday household materials were often brilliant. He had the men gather up all wooden doors, window-frames, and planks that could be salvaged from the houses and the one carpenter’s shop in the camp use them to strengthen that walls and ceilings of the tunnels. In some places, where the shelling had not yet quite levelled a building, the men dug trenches through its rooms and then covered them over with planks and soil – much less arduous work than tunneling. When the building finally collapsed, the falling debris helped to fortify the roof of the underlying passageway.11

After the completion of the “defense axes” tunnels, Ali Abu Toq was martyred by a missile that targeted him in January 1987.

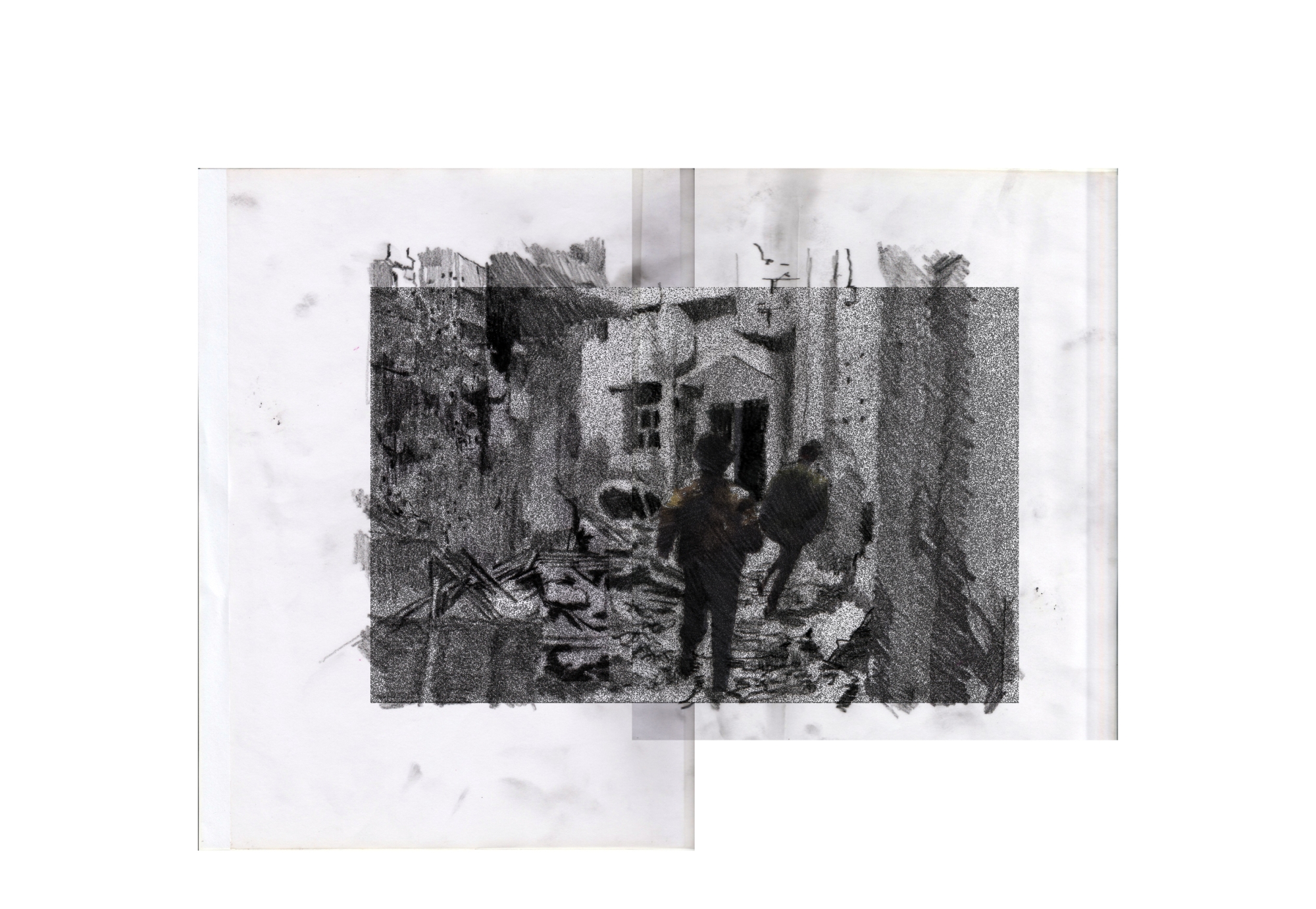

innab-05.jpg

Drawing based on a photo from the personal collection of engineer Hassan Bakir, 2024.

Original image title: Tunnels, Hassan Bakir, 1987.

Proving the existence of these tunnels or tracing their paths is not the central concern here. What truly matters is the understanding that emerges when we move between contemporary urban myth and the notions of sovereignty within urban spaces, and the meaning of resistance. It is like the fear of those who starve and besiege that starvation and siege might be broken – and their obsession with uncovering, exposing, in order to bring a chapter to an end. Sovereignty, after all, extends beyond mere territorial dominance to encompass control over vision itself – over how things are seen and what is permitted to be seen – bound by both visible and invisible borders.

Two girls dash across a green slope, the camera tracing their hurried ascent up a hillside. Moments later, they come rushing back. This is an attempt to draw an image without its sound – not an attempt to erase the violence hidden within it, but to strip it bare. The running here is to escape a sniper’s fire, and the slope is rubble devoured by greenery after destruction. They say that what the camp endured, Beirut endured as well. Yet Beirut withstood its trials only when it fought as if it were a camp – a haunting paradox of vanishing and unveiling. As for the camp, it is left, once again, alone.

I try to locate this slope on a map. Is it in Shatila or Burj al-Barajneh? There is no mention of any reference or source. I choke at all the possibilities – is it the Horsh area? The Martyrs’ Cemetery? Or someplace else?

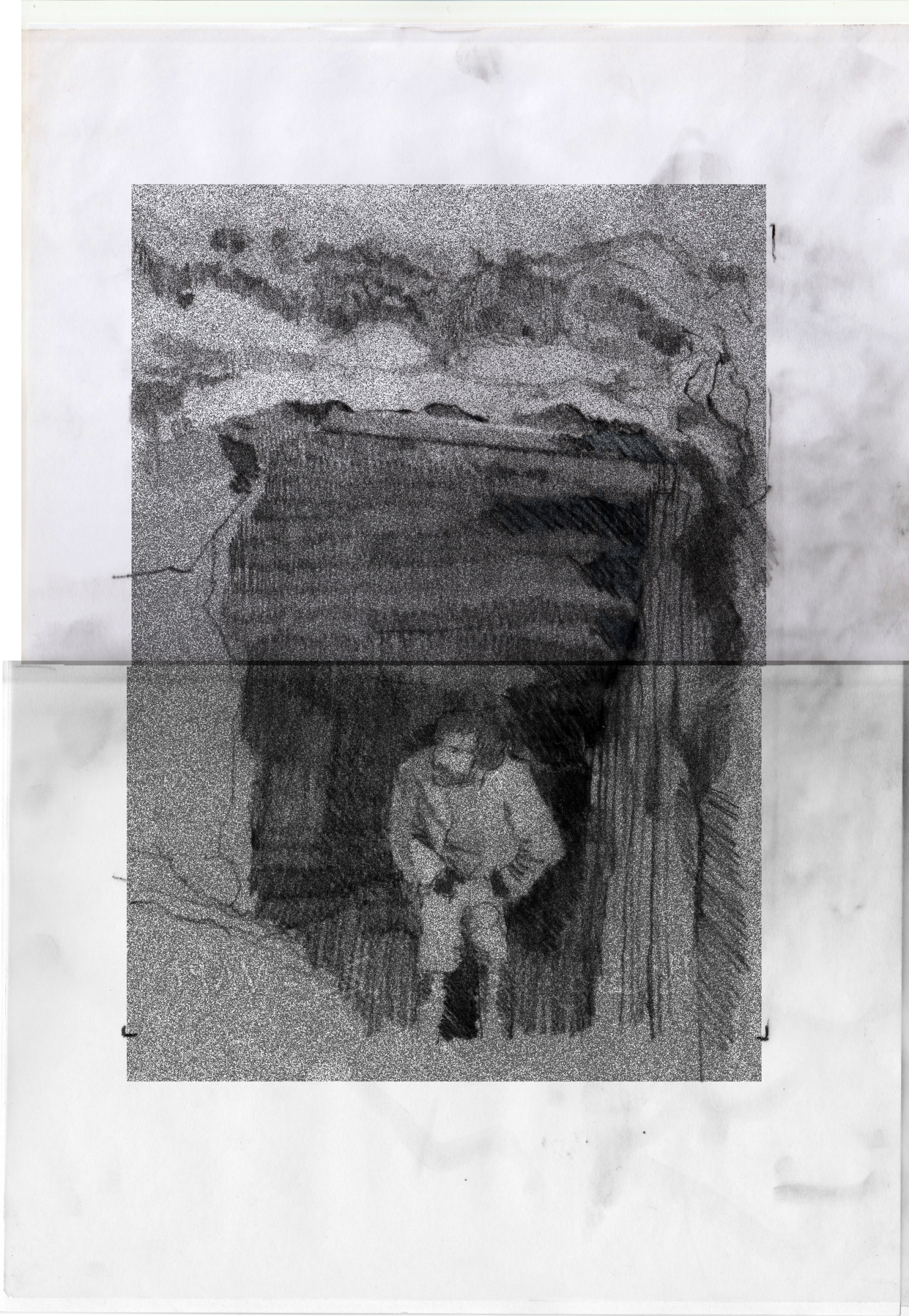

innab-02.jpg

Excerpts from archival materials from 1985-1988.

In a substantial volume published by the Planning Department of the Palestine Liberation Organization, compiling reports from 1973 to 1976 under the title Annual Report: Studies on Some Issues of the People, we find detailed information on public safety, navigating checkpoints, educational courses conducted that year, among others. What stands out most, however, are the small, hand-drawn booklets included as annexes, addressing topics like “How to Build a Shelter,” “How to Build a Barricade,” and “How to Dig a Trench.” These are illustrated with cartoon-like figures of young boys demonstrating how to engage with these spaces. I recall reading somewhere that all shelters built after Tel al-Zaatar were designed with two exits – one specifically for emergencies – driven by a haunting memory: when the shelter entrance was destroyed, everyone was inside and no one survived except for a small girl who was rescued after an agonizing, prolonged effort of digging through the rubble.

At the end of the volume, an additional booklet appears, featuring a map of Palestine adorned with illustrations of its flora. Beyond romanticization, we cannot but link the two imaginaries: the imaginary of the land and the deep, latent knowledge it imparts overlaps with the imaginary of moving through its very core, driven by resistance, toward liberation and return.

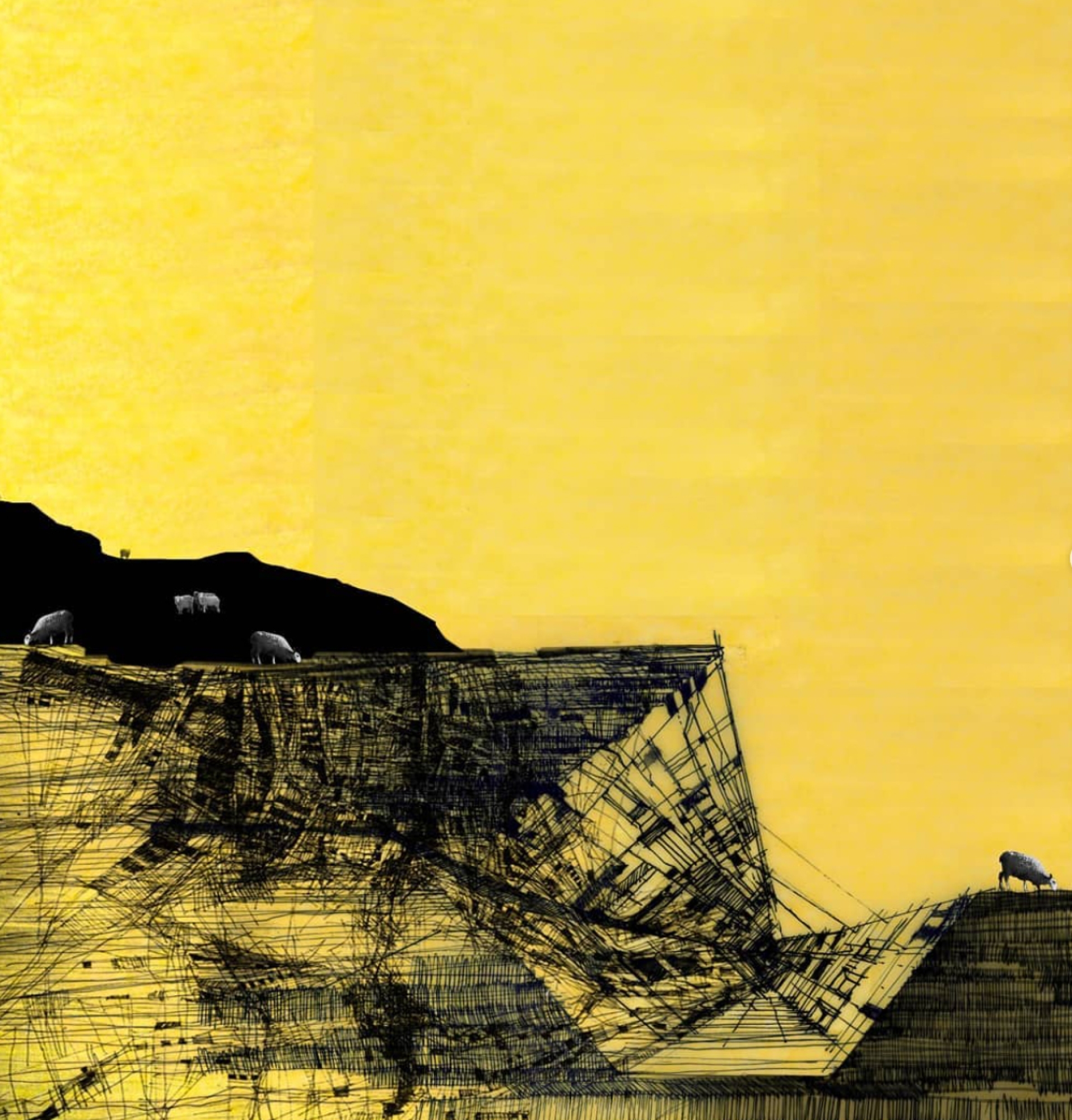

innab-03.jpg

Drawing copied from a diagram published in Technical Report No. (3) entitled “Drilling and Trenching.”

Source: Technical Report – Studies on Some Issues of the People’s War, Report No. (3), Palestine Liberation Organization – Planning Department, Beirut (12/1/1976), p. 21.

innab-04.jpg

A drawing copied from a graph published in Technical Report No. (8) entitled “A Study on Wild Plants in Palestine and Their Nutritional Importance.”

Source: Technical Report – Studies on Some Issues of the People’s War, Report No. (8), Palestine Liberation Organization – Planning Department, Beirut (1/28/1973), p. 31.

Scene Three: The Imagination of the Land, Above and Below

In this section, I will delve into tunnels as a manifestation of the hidden knowledge embedded within the land, examining the interplay between concealment and revelation. This exploration takes on a philosophical dimension, drawing a connection between literary traditions that depict subterranean cities in post-apocalyptic landscapes versus the tunnels of Gaza, in particular. These tunnels manifest the rapid transformation of building know-how latent in a place, evolving faster than the colonizer’s appropriation or extraction – whether through static representations or imposed identities. Such authentic, wretched knowledge has the innate capacity to regenerate and reshape itself into derivative forms, continuously resisting structures generating its absence.

In the tradition of utopian architectural drawings that dream of ideal cities or critique existing realities, most movements tend to create apocalyptic scenes, imagining what we can conceive within the confines of dominant epistemic structures. Massive, brutal structures stretch across the landscape, a response to the post-war period and beyond, as both architectural and literary imagination turn to envisioning life after “point zero” or rebelling against the corrupt city, whether through science fiction or by linking class margins to the invisible aspects of the city. It is said that architectural drawing, historically, has the power to reshape the layers and geography of thought and imagination. In much of 20th-century visual theory, the city is often imagined as a machine – a horizontal cross-section with exaggerated physical layers and interlocking functions. Class-based economic dimensions were projected onto these scenes as spatial functions, resembling a geological vertical section where the alienation and misery of the city’s inhabitants are visible in a never-ending cycle of extraction and exhaustion. The city appears as both itself and its opposite, where alienation is fought by even greater alienation. However, the opposite emerges from the familiar – as the belly of the earth, the underground – symbolizing different meanings for different people.

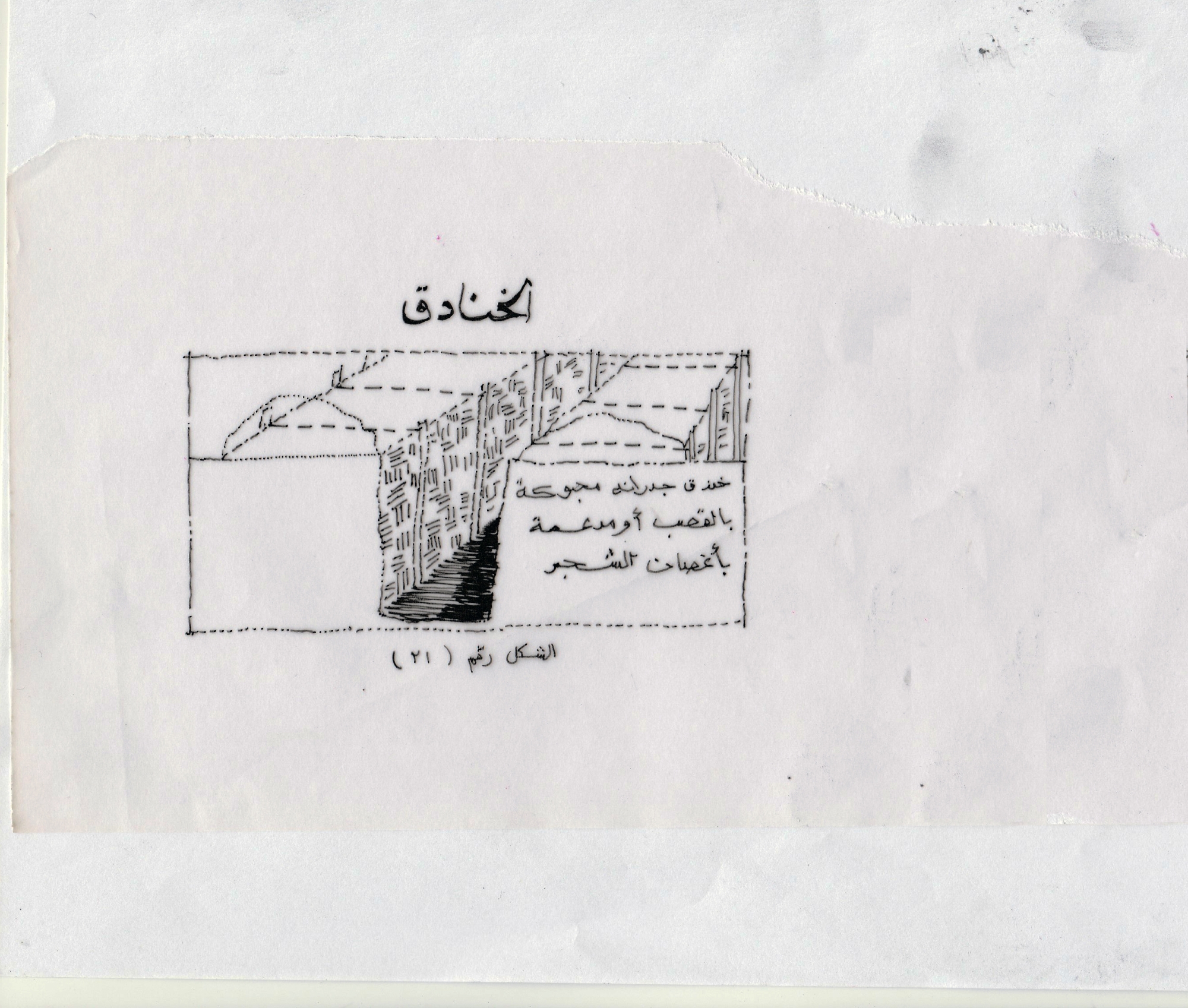

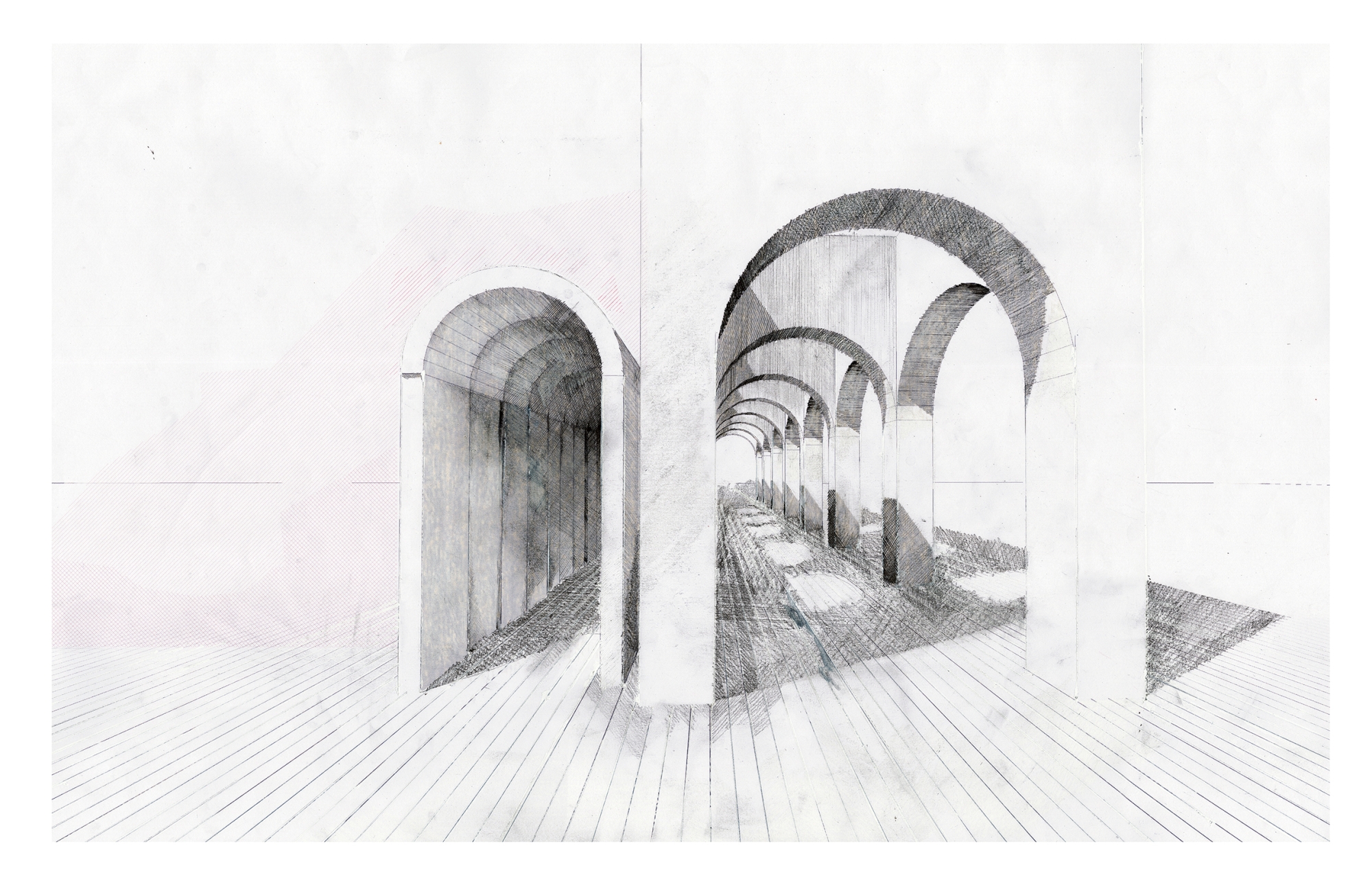

innab-06.jpg

Drawing of an imagined scene inspired by repeated trips between Amman and Nahr al-Bared, 2010.

One way to consider the meaning of building under colonialism is by returning to the fundamental act of building itself – deconstructing the various components, both in their literal and metaphorical senses. These components encompass building materials, know-how, craftsmanship, language, building elements, climate adaptation, environment, among others. It is essential to emphasize that this discussion is not about the simplistic binary between traditionalism and contemporaneity or modernity, but rather about the specificity of epistemic structures that actively resist erasure under the dominance of colonial centrality, existing as a language that doesn’t exist in a binary that seeks to negate it.

In the initial stages of these personal attempts of analysis, the tunnel occupied a central portion of the process, as an architectural element. Its significance lies first in the latent movement it facilitates, and second in its defining characteristic – its “invisibility,” which is essential to its identity as a tunnel. The tunnel’s physical body remains hidden, except that it exists. If we were to extract the tunnel from beneath the earth and expose it above ground, its signifiers would fundamentally shift. The subterranean structural arch could hold authoritarian, hegemonic, even egotistical or decorative connotations, despite the fact that it is structural necessity, once visible under an open sky.

This invites us to consider more deeply the intricate relationship between the land and what lies beneath its surface. The foothills and natural topography have profoundly influenced the architectural imagination behind the Palestinian peasant’s house. The hierarchy of spatial configuration has often been imposed upon us through architectural education, that is steeped in “Western” paradigms. Even when such education strives to embrace the vernacular, it frequently romanticizes the connection to the earth, reducing it to something “primitive.” This risks perpetuating an exoticized view and superficial notions of what it means to reconnect with one’s roots in ways of building. What I seek to underscore is how we can dwell on the hidden knowledge embedded within the land itself, and its imaginary, as a force for resistance and liberation. For instance, by examining a typical vertical cross-section of a peasant’s house in a mountainous region (such as the villages surrounding Jerusalem or Nablus), we can detect a spatial configuration logic that challenges conventional notions of value and significance tied to elevation, or to what lies in front or behind, as opposed to the logic of modern architecture, for instance.

The dome, or the traditional Palestinian peasant house – an element usurped through occupation, the forced displacement of its inhabitants, or outright destruction – invites contemplation on the evolving nature of this deeply embedded architectural knowledge. This architectural form persists through other expressions in vernacular architecture, such as the tunnel.

The tunnel is the knowledge that moves against its siege and captivity, it’s the resistance within and for the land itself. Though over time the dome has been appropriated and redefined within the construction of settler-colonial identity, it paradoxically remains a site that endures, welcoming movement and the return of the displaced. The dome is a fixed entity in perpetual motion, in contrast to the tunnel, which is the movement itself.

One might argue that the dome’s curvature reflects a local knowledge, one that emerges from the imaginary springing out of the land, the same force that shaped construction on mountains and slopes. This knowledge, in turn, evolves into the arched form and walls of the tunnel, creating a hybrid episteme, if we conceive of the tunnel as the dome in motion. These structures of knowledge continue to renew themselves against structures generating their absence.12

How do we look from a point just a few centimeters from our bodies? From a point at a shift so slight it could be nothing but a misalignment of the eyes? How do we step a few centimeters from the body, in order to train our gaze on latent endogenous knowledge and its transformation? And at what moment is this knowledge awoken or provoked into defending itself against its abduction and appropriation?13

Through this proposition as methodology, we try to dig and write non-linearly within the history of countering erasure, materially and figuratively, and towards the preservation of resistance across temporalities.

innab-07.jpg

Arch/Tunnel 2018.

** Note: all the visual material presented in the text was produced by the author.

- 1. In numerous conversations with eyewitnesses to the siege of Shatila during the War on the Camps (1985-1988), there emerges a clear sense of pride in the tunnels dug to defend the camp. Yet, this pride is often followed by a hesitant desire to correct misconceptions: “They’re not tunnel-tunnels.” While these structures might technically be considered “trenches,” these recent clarifications must be understood in the context of the recent fear and stigma attached to the word “tunnel.”

- 2. Following the 1982 Fez Summit, Hafez al-Assad capitalized on the dissent expressed by certain Palestinian revolutionary leaders regarding Yasser Arafat’s leadership. Assad aimed to appropriate the political and military decision-making authority of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), thereby asserting control over the refugee camps. In May 1983, Arafat made a clandestine return by boat.

- 3. UNRWA enlisted the support of the Nahr al-Bared Reconstruction Committee for Civil Action and Studies, a grassroots organization of activists and experts in the fields of engineering and social sciences, who were themselves residents of the camp. This committee had the capacity to act as an intermediary between the agency and the community. It collected information and data on the destruction of the camp, providing a foundation for reconstruction efforts. With its resources and knowledge, the committee helped ensure that the residents’ needs were addressed in both the masterplan and the reconstruction process. Following the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding with the committee in mid-2008, its volunteers and the architects appointed by UNRWA began mapping each house in the camp as it stood before the war, gathering details about the number of individuals in each family and the villages from which they originated. The reconstruction plan was thus based on this critical information.

- 4. The reconstruction plan for Nahr al-Bared camp was divided into eight phases (referred to as “packages”) for logistical and technical reasons. This process began in 2007 and extended until the phased return of displaced residents, depending on the completion of each package. For instance, by the time refugees returned to the first package in the fall of 2011, the majority of the camp’s population – 25,975 Palestinian refugees, comprising 5,720 families according to UNRWA reports – had been living in temporary accommodations or rented apartments with UNRWA’s support. Some families were hosted by others, while others were housed in temporary units (barracks) that UNRWA had constructed or leased in areas surrounding the old camp. These temporary accommodations were notably below the minimum required housing standards.

- 5. Qasim, S. Qasim. “Imagined tunnels between Burj el-Barajneh camp and its surroundings.” Al-Akhbar newspaper, June 17, 2014. https://al-akhbar.com/Politics/33263

- 6. Giannou, Chris. Besieged: A Doctor's Story of Life and Death in Beirut. New York: Olive Branch Press, 2nd edition, 1992.

- 7. Ibid., 38.

- 8. Kataeb militias.

- 9. Ibid., 66.

- 10. Based on interviews with eyewitnesses, Summer 2024.

- 11. Giannou 1992, 98-99.

- 12. Based on “Tread Lightly – Leave No Trace,” an introductory text for an exhibition by the author in 2022-2023.

- 13. Ibid.