A Short Reflection on the “Woman, Life, Freedom” Movement

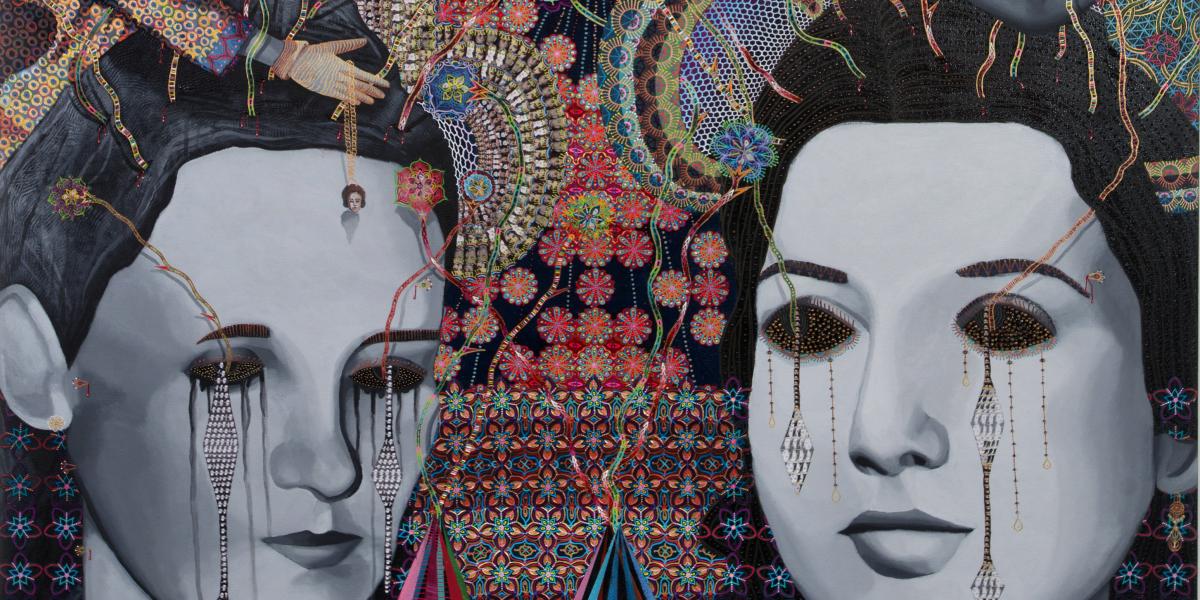

les_femmes_dalger_56_72_x_54_2016.jpg

Les Femmes D'Alger, Asad Faulwell (2012)

This short reflection comes as a later addition to my article in light of the enfolding events in Iran. As this special issue focuses on “Anti-colonial Feminist Imaginaries,” I find it necessary to heed the current movement in Iran in my writing. I add this reflection, therefore, to address three important points that hold significance in our current juncture.

As a feminist who researches and teaches from decolonial, queer, anti-racist, and anti-imperial perspectives, I think it is important to answer one of the most prominent questions about this uprising head on, which is whether the current movement in Iran is a feminist revolution or not. I think that this question in and of itself needs to be divided into two sections. First, what is a revolution? And second, what type of feminism is in question here? Oftentimes in colonial modernity, when we talk about revolution, we mean the sudden replacement of an elite group in a nation-state with another. I do have a hard time reconciling that notion of revolution with feminist ethics, or at least with what I define as feminism - a perspective that can help us see how race, gender, class, ability, and sexuality are historically located and co-constituted. Hence, a revolution that tends to replace a privileged elite group with another cannot be at its core a feminist revolution. However, if by revolution we mean a spontaneous surge that interrupts patriarchal discourse, gendered apartheid, and systematic control over female body in the name of religion and state, then my answer is yes. Yes, what is taking place in Iran, the “woman, life, freedom” movement, is indeed a feminist revolution.

In fact, the slogan “woman, life, freedom” that has become the anthem of this revolution is originally a Kurdish slogan (ژن، ژیان، ئازادی) that had emerged as a response to the state sponsored violence against Kurdish women in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria and soon after became a chant of liberation for Kurdish women from the yokes of patriarchy, state-sponsored oppression, and violence of socio-economic structures embedded in capitalism. Rooted in such radical modes of thinking, “woman, life, freedom” as a movement has the protentional to offer us a transformative and revolutionary path forward.

The second question often raised is whether a critique of Islamic theocracy is Islamophobic. I think we have had plenty of practice with this question, specifically in the case of occupied Palestine. People who call any critique of Israel anti-Semitic (and therefore shut down any meaningful engagement with the violence of the Zionist state) are siding with those who are silencing any criticism directed towards the Islamic republic by considering it Islamophobic. To make equal and put in proxy any criticism against an institutionalized form of religion with the religion itself is problematic, short-sighted, and dangerously limiting. We should be able to engage in meaningful conversations about how Islamic nationalism, like any theocratical and nationalist project, perpetuates patriarchy, misogyny, queerphobia, etatization, elitism, and an exclusionary ideology that translates into violence against ethnic, sexual and religious minorities.

Lastly, as an Iranian feminist and lawyer who has been forced into exile to Canada over a decade ago, I am deeply aware of the need for a multilayered reflection on the current events in Iran and the historicization of all that takes place in a geography marked by imperial meddling and intervention. But such a reality should not prevent us from recognizing women, minorities, and other Iranians’ genuine demands for regime change. The ever-present imperial gaze in the region should not prevent “us,” leftist and anti-imperial feminists, from attempting to create a transnational feminist solidarity that amplifies the demands of Iranian women. Because to be a leftist/anti-imperial feminist doesn’t mean to be trapped in an either-or positionality where you have to always choose a side – i.e., you’re either in support of Iranian protest or you’re critical of imperial agendas in the region.

Rather, it is a call for all of us to move beyond the box in which we always circle. It is to use whatever platform is provided to us to amplify the voices of Iranians from inside unapologetically while maintaining a critical eye. It is to rescue our imagination from the fear of what can and cannot be co-opted and instead dream about a future we want to create. To hell with liberal feminist agendas and white savourism, to hell with neoconservative propaganda. We need a space to think for ourselves, to imagine for ourselves, to talk to each other, and to DESIRE. We ask our leftist and feminist allies to hear “us,” because Iranian women who are queer, poor, and/or silenced need all the platforms they deserve. I know it is hard for us – those of us who are living in the west and whose bodies are familiar with alienation and white supremacy; we often are afraid of hearing our own desires and hopes for the future of Iran. But at least let us dream, let us hope, even if this hope is short-lived, for a future without heteropatriarchy.

Long live Woman, Life, Freedom.