Toward a Liberation Pedagogy

This contribution brings together three practitioners working across research, education, curation, and communal theatre in the UK, fields that are deeply implicated in the violence of colonial modernity. We engage in a dialogue across our locations within extractive institutions, specifically Higher Education and heritage/cultural organisations, with the intention of imagining and enacting a language-practice of anticolonial feminism built through embodied experience and collaborative action. Following our intuition and the teaching of feminist, queer, Indigenous, and Black scholars, we centre embodiment, materiality, affect, aesthetics and relations of care in our steps toward the future.

Our piece takes the form of an evolving conversation that builds upon and exceeds “the word” as a mode of communication and expression. We understand the privileging of written language (primarily English), as well as the visual, in the production and transmission of knowledge to be an effect of ongoing colonial domination. Against this current, we explore the motion/s of decolonial and anticolonial feminisms, which move within other scripts and sites of knowledge including land, body, breath, spirit, and sensation. As such, we propose that anticolonial knowledge is cultivated in ways that foster connections across time, space, struggles, and imaginaries.

Working with art, scholarship, performance, dream states, haunting, discomfort, prophesy and more, our dialogue takes aural/sonic, visual and written forms. We depart from two suggestions which focus attention on processes and practices: 1) methods are transformative opportunities for educators in the classroom and practitioners in the field; and 2) lived experiences are sources of critical reflection and emergent theory. Thinking and working across mediums, institutions, and sites of power, we aim to disrupt, reclaim, and transform possibilities, asking tenderly and with rage, whose desires shape our work and practice?

Featuring audio-visual work by:

Jamal Abu Eisheh

Malo Trapp

Sila E.

Asha Ali

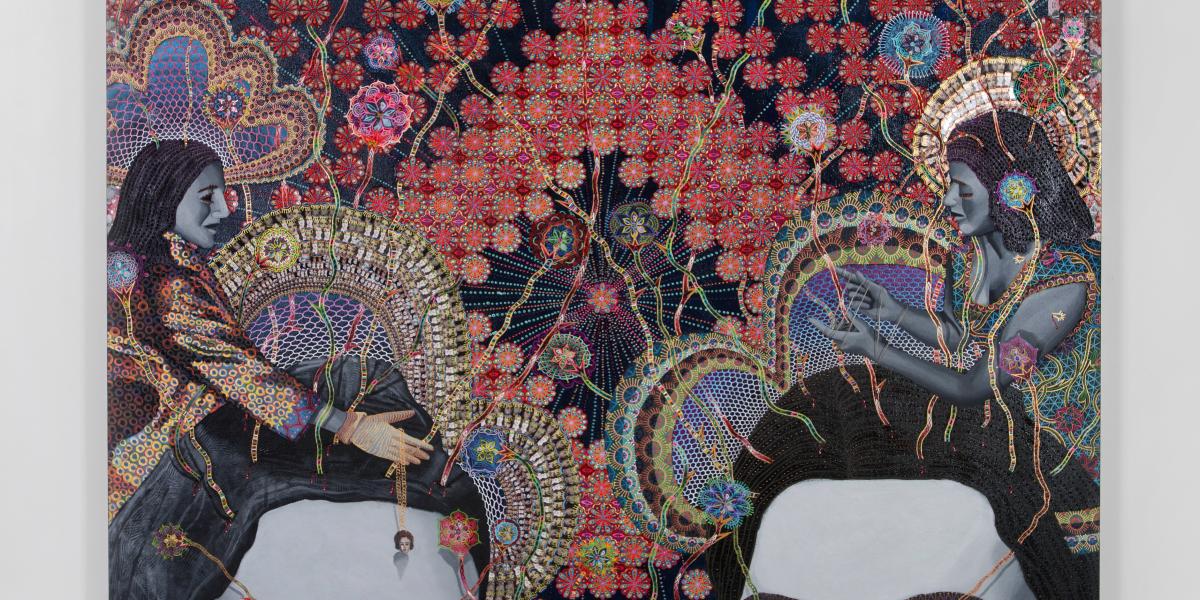

les_femmes_dalger_56_72_x_54_2016.jpg

Les Femmes D'Alger, 2012

Theoretical talk … invites readers to engage in critical reflection and to engage in the practice of feminism.

- bell hooks, “Theory as Liberatory Practice”1

***

What happens when we refuse?

What can we do, when we take as our starting point/s something other than what is expected or accepted? Whose experiences, stories, sensations and dreams are invited when we work in these ways? How does that knowledge feel – what does it tell us, (how) can it transport2 – and what kinds of futures could we move toward?

Our engagement grows from a presentation at the 2021 conference of the British Society for Middle Eastern Studies (BRISMES). Though the dialogue below unfolds between Kanwal (KH) and Katie (KN), we built this discussion with curator and practitioner Amal Khalaf3 (Serpentine and Cubitt galleries), who ran the Language, Resistance, Theatre workshop described later. While working with us to develop this piece, Amal was also bringing together the final year of the recently launched Radio Ballads project as its principal curator. Radio Ballads is the work of four artists who spent more than three years in social care and community services settings in Barking and Dagenham (UK), and was “created through collaboration with social workers, carers, organisers and residents which explore stories of labour, and who cares for who and in what way.”4 The concerns raised by that specific project run in tandem with our work together, and Amal’s theoretical reflections on her experience as a practitioner in the (also extractive, colonial) cultural heritage industry are deeply present in the thinking behind this piece.

At BRISMES, we enacted a conversation titled “Radical pedagogy and transformative tools for researchers and educators.” We spoke across our institutions and practices in hopes of unearthing seeds of disruption, sharing tools that could be passed hand to hand (recognising how we are already forging them) and speaking their existence in ways that might nourish collaborative/collective action.

This article works from two themes, or points of departure. One: lived experiences are sources of critical reflection and emergent theory. We walk with bell hooks, who says that we examine the everyday to make sense of it and to imagine possible alternatives – and that the work of theory is a necessary practice within a framework of liberatory activism.5 And two: methods are transformative opportunities for educators in the classroom and practitioners in the field. Thinking and working across mediums, institutions, and sites of power, we aim to disrupt, reclaim, transform, and develop possibilities.

Seeing power

KN: Sitting with this piece and these thoughts for over a year has meant watching as they change shape, grow, and move. I write this now with some distance, in a moment after the intensity of my spring teaching term and before turning to a season of marking, supervision, and research. It feels like a time of pause, an opportunity to gather thoughts and form ideas. To reach toward something new. But it is also a time of return, as I know these sensations of calm and renewal to be cyclical – something like an annual appointment with perspective. I understand how these “breaks” materialise as relief and the promise of restoration. But I also see how their reparative function masks the damage (yet to be) done, enabling us to repeat the process with the hope that this time it will be better, easier or different. I think what is sitting in my heart at this moment is how to hold this together: a will to do things otherwise and build things elsewhere, in ways that keep sight of power – and yet refuse it as totalising.

This might be what María Lugones meant when she challenged us to work beyond “the logic of power” in her theorisation of/toward decolonial feminism.6 It is somewhat amusing because for years I’ve puzzled over this turn of phrase – often in the classroom with students – asking, “but what does she actually mean?” Perhaps I’ve known all along, or could only reach a state of understanding through inhabiting the tension, personally and professionally. What Lugones proposes (insists!) is not an abstract theoretical musing, something to be puzzled out by refracting ideas through frameworks. Rather, it is something to be done7 – a practice that we envision and embody because we must. Lugones writes,

As the coloniality infiltrates every aspect of living through the circulation of power at the levels of the body, labor, law, imposition of tribute, and the introduction of property and land dispossession, its logic and efficacy are met by different concrete people whose bodies, selves in relation, and relations to the spirit do not follow the logic of capital. The logic they follow is not countenanced by the logic of power. The movement of these bodies and relations does not repeat itself. It does not become static and ossified. Everything and everyone continues to respond to power and responds much of the time resistantly – which is to say not in open defiance, though some of the time there is open defiance – in ways that may or may not be beneficial to capital, but that are not part of its logic. From the fractured locus, the movement succeeds in retaining creative ways of thinking, behaving and relating that are antithetical to the logic of capital.8

I take comfort in how this vision creates space for ambiguity and failure, adaptation and renewal as part of a new/old way of being in the world. It offers us a means to respond and resist that feels radically generous. It gives us permission to try again.

KH: Our conversation with each other about doing things otherwise here, joins the ongoing conversation about how that might be done. It engages with the call made by Akanksha Mehta, who asks in Volume 5 of Kohl, “What does it mean to be a feminist teacher and engage in feminist pedagogical practices?”9 We are also drawing on a longer history of thinking about radical pedagogy (hooks, Freire, Boal and more – including many unpublished practitioners). As has been done before in other contexts, we are thinking about sites of education being enacted as sources for social transformation, which I will come back to later.

I want to start by working through the question: situated as we are within colonial extractive institutions, what is our relation to knowledge? We can think with Michel-Rolph Trouillot about how this relationship – which is invested with power – is obscured, as knowledge travels, enters, and circulates within institutions, and is disseminated through various institutional outputs. How do we make choices about what we share? As we move through the business of knowledge production, do we ask ourselves: who needs to know this, and why? Trouillot says, “the ultimate mark of power may be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.”10 How can we keep the roots of meta-structures of domination and extraction clear and visible to ourselves, and at the same time work, as Chandra Mohanty says, as “insurgent”11communities within our institutions? How can we develop working practices which honour the engagements we have with the peoples, lives, histories, ideas that we work with?

KN: Yes, we are coming to a shared concern: what does it mean to work “beyond the logic of power” and build “insurgent communities” within extractive institutions? What does that require of us? In other spaces and times, I’ve named academia and Higher Education as explicitly neoliberal,12 shaped by capitalist ideals to the extent that (successful) teaching and learning yields subjects who reproduce the prevailing order and the violence that sustains it. I know that among us, we follow Paulo Freire and bell hooks in refusing that logic, and instead insist that education can be otherwise – that knowledge cultivation and sharing can move us toward “critical consciousness” (conscientização) and practices of freedom. Rather than reproducing the logics of extraction and accumulation, this orientation acknowledges our embeddedness in the world and its inequalities, our entanglement with each other and our environment, and our ability to act upon and transform reality.13 This is a hopeful and powerful vision, a world that many of us try to build and inhabit – through our teaching and learning practices, our participation in union activities, our creative and collaborative research, and our personal relationships.

But I am not so sure that the University can ever be this place of generative and generous (radical) possibility. I remain troubled by the feeling that critical consciousness cannot emerge from its structures and values by virtue of their proximity to power, just as I question what kind of “freedom” these institutions would consent to, if possible, at their own (perceived) cost. We already see the disjuncture between “freedom” and liberation on our campuses – for example, in the battles waged against transphobic, misogynist, and racist speakers openly hosted by Universities, and for a commitment to boycott, divestment, and sanctions in support of Palestine. Are these the bodies from which individuals or movements might emerge to critically intervene in the world, in ways that acknowledge, refuse, and dismantle power? To build the world anew?

I’ve wrestled with this feeling – something that hovers between optimism and despair – throughout my time in UK Higher Education. There are ways to frame our work which make it feel less hypocritical, such as “becoming bad subjects” within neoliberal institutions or “teaching to transgress” the capitalist systems that provide vocation and education.14 If told regularly, these stories might hold at bay the suspicion that we are subscribing to false consciousness15 or cruel optimism,16 under the guise of resistance or revolution. In fact, these stories might be the only way to survive, strive, and live on in extractive institutions (if that is what we want to do).

Learning from legacies: contesting power and building other bases

KH: This seems like an important balance: to hold close our awareness and aspirations, and work to enact them, while knowing that these practices operate within a space (Higher Education, galleries, museums); and what we aspire to is avowedly not what this space is for. More broadly speaking, I have a sense that hope doesn’t take shape by itself. It is often – if not always – framed by, laced with, or sitting on the thin edge of danger, vulnerability, or despair.

And again, while we are clearly not working under the same circumstances, nor from the same social location, I think that there is so much to learn (and take inspiration from) in the historical experiences of those who have faced a much more palpable danger: I’m thinking here about movements for anti-colonial liberation and revolutionary transformation, and their educational commitments, practices, and methods. What we repeatedly see in these experiences are: relations and communities formed outside the official educational institution; education in the service of material social transformation; the exploration of lived experiences – and the building of alternate imaginaries and realities through education. These practices, and the centrality of education within them, were an important part of the work of national, anti-colonial, and revolutionary movements in the MENA region during the long first half of the twentieth century. Teachers and students engaged in burgeoning political communities outside of the university in Beirut, Cairo, Kuwait City, Nablus – and in many other locations too.17

It’s worth adding that as well as academics and university students engaging in national / radical politics, educational ecosystems were also cultivated in spaces with no direct connection to the university – at professional, social, and sports clubs, during after school classes, in refugee camps and village squares. Learning about these experiences invites us to think about how the spaces we teach and work in are situated within a larger field, and to see the lines that divide inside from outside as being porous and susceptible to being moved or crossed. It also asks us to read the practices of anti-colonial and liberation movements which were deeply entangled with education as more than just a historical “thing that happened.”18 I think we have a lot to gain by thinking about these practices and the development of methods within them as part of a liberation pedagogy.

On the other hand, arguably, the institutions we find ourselves in today perform largely in the service of the powers which destroyed much of what I have described above (sometimes with the help of those who position their thinking with the subaltern, such as James C. Scott19). The way out of this seems to be to think clearly about what we can and want to do in and with these spaces and resources. As Mohanty says, “we bear a deep responsibility to think carefully and ethically about our place in this academy, where we are paid to produce knowledge and where we have come to know the spatiality of power needs to be made visible, and to be challenged.”20

KN: Let’s push further here. Let’s think clearly about what we can and want to do! But also what we must do, which is intimately connected to who we are responsible to. What happens if we accept discomfort with/in extractive institutions as a condition of the present – and at the same time expand the space of the future (here and now) by growing our capacity to work antithetically? Working slowly, carefully, and clandestinely in ways that echo the amazing examples you’ve just provided. While institutions might imagine us to be labouring in the interest of extraction and accumulation, we can be building alternate realities by organising beneath their surface/s.

There is something about the passage by María Lugones that enables this, a way of being in two worlds or working on different levels simultaneously. I want to bring us back to her words as a means of moving forward. Let’s recall:

Everything and everyone continues to respond to power and responds much of the time resistantly – which is to say not in open defiance, though some of the time there is open defiance – in ways that may or may not be beneficial to capital, but that are not part of its logic.21

I admit to having read this article multiple times without pausing at the section that now strikes me as so compelling. There is a danger that I take solace in these particular words today as a new iteration of the familiar story – one that justifies our continuing presence and investment in extractive institutions. But I think it is also possible for us to use those structures and systems against themselves, to make the most of the resources, platforms, and people they bring together. As you also suggest! Planning, building, gathering, connecting, dreaming, and doing/being otherwise as we anticipate the moment to rise and transform the “here and now” from which we emerge.22

Pedagogies and/as praxis: some thoughts on how

KN: So the question is definitely one of method – how exactly do we work in these ways, having arrived at a place where its necessity is blindingly clear? In The Undercommons, Stefano Harney and Fred Moten catch us with this claim: “THE ONLY POSSIBLE RELATIONSHIP TO THE UNIVERSITY IS A CRIMINAL ONE.”23 I’ve felt and seen myself attempting to untangle the knot of “how” in so many ways, but always with a belief that the University (as an institution) can and will be better. That it is worth our investment as we try to transform it, culturally, structurally, and politically. I haven’t known how/whether to hold this hope alongside the certainty that the changes we pursue cannot be embraced by the University, as they will ultimately undo it. Instead, Harney and Moten invite us into fugitivity:

[I]t cannot be denied that the university is a place of refuge, and it cannot be accepted that the university is a place of enlightenment. In the face of these conditions one can only sneak into the university and steal what one can. To abuse its hospitality, to spite its mission, to join its refugee colony, its gypsy encampment, to be in but not of – this is the path of the subversive intellectual in the modern university.24

“To be in but not of.” This is to accept that our labour might be captured or extracted (even willingly) by the institution – that we might “be beneficial to capital”25 – but to do our work beneath the surface, refusing to serve its logics by “disappear[ing] into the underground.”26 This is a space/time of the future, where we are learning, building, nourishing, creating, and preparing for a new order. It is populated by comrades whose work may be applauded and marketed by our institutions, but who constitute a danger to its existence by virtue of their fugitive labour. Our ability to be present in parallel leads us toward the how – to give some but not all of ourselves, to keep sight of the surface and inhabit the underground, to develop a language and praxis of abolition and revolution.

KH: Also thinking about the question of “how,” I feel compelled to offer a sort of caveat – that there is no big WOW, just deeply-considered, small, everyday ways of working that speak to the ideas and concerns we have been discussing. I’ll share some exercises borrowed from theatre and drama practitioners that can be brought into the teaching or classroom space which highlight this. Through them, I am also asking: can we meet each other in other ways?

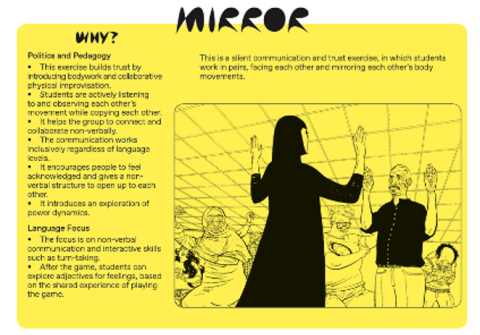

At a morning MA seminar for students on the course “Gender, Sexuality and Violence in Palestine/Israel” at the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, I began our session with a quick warm up game taken from the methods of Augusto Boal,27 and practised in new ways at a workshop by ACT-ESOL Language, Resistance, Theatre. Organised by a collective in which Amal has played a leading part and based on Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed, this method explores “the ways that language, political theatre, and action can be used to assemble individuals for the purposes of transformation and resistance.”28 The exercise is included in the ACT-ESOL resource as “Mirror” and described as an activity in building trust. The students who wished to take part worked in pairs, with one following the movement of the other’s hand before switching roles, one leading the movement and the other mirroring. A few subtle shifts took place during the brief exercise – most notably, because the game relies on non-verbal communication, it shifted the dynamic in which the most confident or most comfortable speakers of academic English language play a dominant role in the group. It encouraged members of the class to look at one another, and to lead by paying attention to and reading non-verbal cues. At the same time, it occurred to me that the exchange was still being shaped by other power dynamics, including race, physical appearance and clothing, and dis/ability. For a myriad of reasons, people don’t necessarily always want to be seen, or known. I think of this also when I read about power and invisibility in Trouillot, and how being invisible to power can preserve those people who do not wish to be seen and their work. Both these understandings can be carried into and inform our research and teaching.

Figure 1. Mirror Games and Exercises card from the ACT-ESOL publication, Language, Resistance, Theatre.

In another icebreaker, we played a game of name introductions paired with physical gestures, this time online using the Zoom application in gallery view, as taught to me by the Bahraini theatre practitioner and teacher Ruqaya Aamer.29 The first player says their name and performs a static or moving gesture, which the rest of the group members then imitate and continue or hold until the next name-introduction and gesture is made. Something joyful unfolds as all the small Zoom windows fill the laptop screen with images of participants responding to the initial gesture. Again, we are developing responsiveness, building rapport, breaking the ice – playing! In these theatre exercises, we are also laying some claim to time – and how we might use it briefly towards building engagements through play, instead of rigidly committing to transactional or productivity-oriented time.

KN: It strikes me that these playful practices enable us to see the world as it is – and at the same time draw us toward worlds that might be. There’s something here about re-thinking and re-building everything from the ground up – this is what decolonial and anticolonial praxis entails. To go back to Higher Education pedagogy, it is so much more than revising our reading lists or adding topics! As you say, the real work is done on an everyday basis, not least in the ways we encounter and relate to each other. The practice/s you describe in your classrooms require self-reflexivity, risk, trust, communication, and creativity – these are not contractual agreements, signed on the first day of term and then forgotten. They emerge through our experiences of being together. Admittedly, these experiences are sometimes (if not often) uncomfortable as we navigate violence and domination, differing social locations, and the politics of voice and representation. This means that the time of decolonial and anticolonial teaching and learning is necessarily slower, just as its spaces are charged with emotion and sensation.

What I’m getting at is the effort it takes to work in this way – the piece by Akanksha Mehta that you mentioned earlier alerts us to the labour of care and the doing “extra” that transformative pedagogies require. But I think we are also talking about how the question of who – who is at the centre of our work? – shapes (or even determines) our methods, our how.

KH: Yes, working in this way (in the way you do!) is effortful – also in a theatrical sense, in that there is a great deal of thinking and preparing which goes into something that looks spontaneous, effortless, or just like playing. It also means that sometimes every class feels like an event, and the group dynamism and communal learning, thinking, and exchange generates a moment that cannot easily be encapsulated and changes every time, even with the same materials and questions. All of this speaks to the question earlier about “what do we want to do with this space and these resources?” – what kind of teaching environment/s and experience/s do we want to create? And crucially, as you mentioned: whom is it for? When I think about the idea of centring lived experiences while teaching the MA course on Palestine at the University of Exeter (as opposed to teaching English to migrants and asylum seekers, which the ACT-ESOL practitioners do) I am primarily concerned with building understanding through the lived experiences of people from Palestine, and very conscious of the need to shift focus from gazing through the lens of a white colonial extractive institution in the UK. This approach to learning involves grappling with discomfort and learning to de-centre.

Teaching students to de-centre themselves – by asking who is known? who is know-ing? who is know-er?30 – has also been part of the code of practice shared at the start of the course, which we adapt and adopt in our classroom space. As well as encouraging students to develop reflexivity – we call it “pass the mic”31 – I inform them that I use a “stacking” method to call on students who want to make interventions. Through stacking, members of the group who have not previously spoken, those who speak less, and those who are structurally marginalized “get the mic” when they decide to join the conversation. We pass the mic to them before someone else who may have raised their hand first or shared a number of interventions already. It is an imperfect system, but it does set a precedent for self-reflexivity, as well as shaping a distribution among contributions.

Moving toward decolonial and anticolonial possibilities

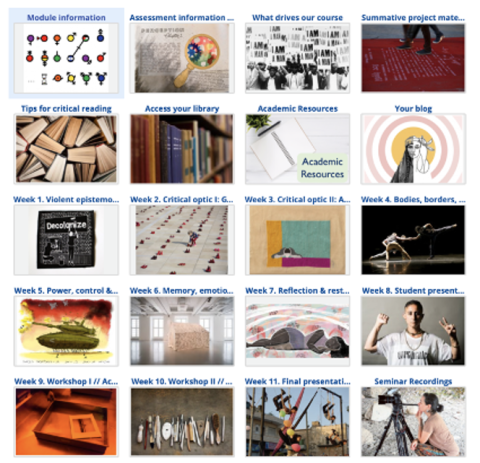

KH: I think we can also start with your course itself, which I worked on as a teaching assistant. The course was the structure for the alternative approaches and possibilities I have spoken about here. In this case, the lovingly curated and regularly evolving course content32 provided the foundation and nourishment for our collective foray into a radicalising education. The essential course content includes rigorously updated critical readings, along with extensive additional material for students who wish to develop a greater engagement with concepts. The weekly “readings” are often intense, challenging and enriching, and offer a kind of “sensuous knowledge” which Avery Gordon calls, “receptive, close, perceptual, embodied, incarnate [...] It tells and it transports at the same time.”33 The “readings” include short films, literature, artworks, podcasts, physical theatre, music videos, digital archives and online information repositories and projects. These resources open up worlds to students for a deeply felt engagement with the thematic and theoretical elements of the course. Working with these mediums has been conversation-provoking and pleasurable, and has encouraged students to explore further and share their own rich array of formats, mediums, and materials from which we can learn.

Figure 2. Homepage for ARA3200, “Gender, sexuality & violence in Palestine/Israel” by Katie Natanel, Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter.

The structure of our course, as well as its content, makes this type of work possible. You adapted it so that assessed work includes three elements: weekly headlines, a student reflective diary and a summative project. The weekly headline exercise asks students to read and share headlines and resources related to Palestine based on the thematic of the week, and “to challenge the presumed boundary between academia and ‘the real world’, foregrounding the many ways in which lived experiences are the basis for knowledge, theory and concepts.”34 The reflective diary blogposts are closely tied to the course essential readings and encourage students to take part in the process of knowledge production knowingly. Through it, they map, explore, and raise questions about their “experience/s of learning and cultivating knowledge.”35 The blog becomes an important site in the shared learning space we are creating, which feeds into students’ summative projects. But it also is a forum where participants can get to know one another, and develop conversations on course material at a different time-pace to the seminar room.

The final/summative project invites students to produce “a creative research project (group or individual), which engages with key themes and topics from the course.” It includes an essay-style element in which the theoretical engagements and thinking behind the project are made clear, but also opens up an opportunity to think about forms that knowledge can take – and how some forms might cross beyond the limits of academic spaces, while remaining deeply informed and critically engaged. This can both inspire and terrify students! We need to be attentive to the material reasons that students might feel less equipped to produce such work, but more often than not it allows students to thrive through intellectual curiosity and creativity. It demands a more complex assessment format (and longer assessment time!), as well as a greater level of engagement from teaching staff and other students in the classroom community. To support this, the course is structured to be more heavily taught at the start of the term, before developing into a discussion-led middle section, and paring off into workshop format at the end.

Examples of projects produced by students illustrate the beautiful and provocative possibilities of working with methods and a structure (where possible) that are critical, creative, communal, engaging, and committed to anti-colonialism. With their permission, we are honoured to share two projects here:

● “My Mind is a Checkpoint No One Can Cross” (2021), by Sila E. and Asha Ali; experimental dreamscape.

● “Business as usual in occupied lands” (2021), by Jamal Abu Eisheh and Malo Trapp; narrative documentary.

KN: These are worlds we can build and inhabit – they hold what was, what is, and what will be. They are spaces of secrecy, criminality and solidarity, revolt, retreat, and release.36 They are sites of study and strategy, offering care, love, nourishment, and pleasure. These fugitive worlds are where we meet and dream together – where we hold each other up when the doing feels too much, where we take turns carrying the weight. They are not ephemeral, but rising and receding according to our needs and careful judgement/s of the moment. We can be there learning, agitating, disrupting, growing, and laughing – and at the same time here, rising to the surface to steal what we can.

I am starting to understand how we might create these worlds with people we meet through the extractive institutions we work in (but are not of) – on picket lines and Zoom calls, in classrooms and hallways, at protests and workshops – in time that may be “stolen” by virtue of the systems and norms that define criminality, but in truth is reclaimed, re-purposed, and re-valued. Finding our communities can be an act of recognition, seeing/hearing/feeling/sensing yourself in another (even if a fleeting glimpse) or something more radical: recognising “[…] that this shit is killing you, too, however much more softly.”37 I think this is partly what leads us toward decolonial and anticolonial feminist praxis, pedagogies, and thought: the belief that when we work in antithetical ways we are also in motion toward each other.

KH: Yes! In doing, in praxis, we seek out “the entanglement of individual experiences with collective emancipatory processes”38 – but also sit with incommensurability, moments of (seeming) impossibility. We are after all working in white colonial institutions, all the while building practices and approaches through learning from creative, feminist and decolonial pedagogies. It means, as Dian Million says, that to “decolonize” is to understand as fully as possible the forms colonialism takes in our own times39 and to do, as you suggested, what María Lugones challenges us to do – to gradually learn to work “beyond the logics of power” that are forced upon us, differentially.

- 1. hooks, “Theory as Liberatory Practice,” 8.

- 2. Gordon, Ghostly Matters, 198. See also Larry Mitchell’s The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions as an account of – and inspiration for – working in these ways.

- 3. You can see other work by Amal here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19436149.2013.822240

- 4. https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/radio-ballads-exhibition/

- 5. hooks, “Theory as Liberatory Practice,” 8.

- 6. Lugones, “Toward a Decolonial Feminism,” 755.

- 7. Gordon, Ghostly Matters.

- 8. Lugones, “Toward a Decolonial Feminism,” 754.

- 9. Mehta, “Teaching Gender, Race, Sexuality,” 24.

- 10. Trouillot, Silencing the Past, xi.

- 11. Mohanty, “Neoliberal Projects.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhyCLtnGE2A

- 12. Natanel, “On Becoming ‘Bad Subjects’;” Chappell, Natanel and Wren, “Letting the ghosts in.”

- 13. Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

- 14. Natanel, “On Becoming ‘Bad Subjects’.”

- 15. Molyneux, “Mobilization without Emancipation?”

- 16. Berlant, Cruel Optimism.

- 17. Al-Rashoud, Modern Education; Khaled and Hajjar, My People Shall Live, 39, 41; Nabulsi and Takriti, “Learn the Revolution;” Moed, Educator in the Service of the Homeland, 76; Salih, The Stillborn Notebooks.

- 18. Sontag, On Photography, 5.

- 19. https://twitter.com/vijayprashad/status/1493014216235798529?s=20&t=b-bTnKeve2PW9Fc9Llbfeg

- 20. Mohanty, "Neoliberal Projects.”

- 21. Lugones, “Toward a Decolonial Feminism,” 754; emphasis added.

- 22. Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 45.

- 23. Harney and Moten, The Undercommons, 26.

- 24. Ibid., 26.

- 25. Lugones, “Toward a Decolonial Feminism,” 754.

- 26. Harney and Moten, The Undercommons, 26.

- 27. Boal, Games for Actors and Non-Actors.

- 28. https://d37zoqglehb9o7.cloudfront.net/uploads/2020/03/act_esol-_language_resistance_theatre_2019_0.pdf.

- 29. https://www.instagram.com/makankom/?hl=en.

- 30. Kilomba, “Decolonising Knowledge.”

- 31. https://exeter.padlet.org/knatanel/5ykvxrl2fmx2qi8i

- 32. https://vle.exeter.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=9706

- 33. Gordon, Ghostly Matters, 98.

- 34. “Weekly Headlines” https://vle.exeter.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=9706§ion=5

- 35. “Reflective Diaries” https://vle.exeter.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=9706§ion=5

- 36. Harney and Moten, The Undercommons.

- 37. Harney and Moten, The Undercommons, 141.

- 38. Zapperi, “Kader Attia.”

- 39. Million, “Felt Theory.”

ACT ESOL. “Language, Resistance, Theatre.” Serpentine Galleries, 2019. https://d37zoqglehb9o7.cloudfront.net/uploads/2020/03/act_esol-_language_resistance_theatre_2019_0.pdf

Al-Rashoud, Talal. Modern Education and Arab Nationalism in Kuwait, 1911-1961. Unpublished PhD Thesis, SOAS, University of London, 2016.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

Boal, Augusto. Games for Actors and Non-Actors. London: Routledge, 2002.

Chappell, Kerry, Katherine Natanel and Heather Wren. “Letting the ghosts in: re-designing HE teaching and learning through posthumanism.” Teaching in Higher Education, 2021, pp. 1-23. DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2021.1952563

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin Books, 2017 [1970].

Gordon, Avery. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. New York: Minor Compositions, 2013.

hooks, bells. “Theory as Liberatory Practice.” Yale Journal of Law and Feminism, vol. 4, no. 1 1991, pp. 1-12.

Khalaf, Amal. “Squaring the Circle: Bahrain's Pearl Roundabout.” Middle East Critique, vol. 22, no. 3, 2013, pp. 265-280.

Khaled, Leila, and George Hajjar. My People Shall Live. Toronto: NC Press, 1975.

Kilomba, Grada. “Decolonising Knowledge.” Akademie der Künste der Welt (Academy of the Arts of the World), 24 March 2016. https://www.adkdw.org/en/article/937_decolonizing_knowledge

Lugones, María. “Toward a Decolonial Feminism.” Hypatia, vol. 25, no. 4, 2010, 742-759.

Mehta, Akanksha. “Teaching Gender, Race, Sexuality: Reflections on Feminist Pedagogy.” Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, vol. 5, no. 1, 2019, pp. 23-30. https://kohljournal.press/reflections-feminist-pedagogy

Million, Dian. “Felt Theory: An Indigenous Feminist Approach to Affect and History.” Wicazo Sa Review, vol. 24, no. 2, 2009, pp. 53-76.

Mitchell, Larry. The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions. Nightboat Books, 2019 [1977].

Moed, Kamal. “Educator in the Service of the Homeland: Khalil al-Sakakini’s Conflicted Identities.” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 59, 2014, pp. 68-85.

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. “Neoliberal Projects, Insurgent Knowledges, and Pedagogies of Dissent.” Cornelia Goethe Center, Frankfurt, Germany, December 16, 2015. YouTube, February 15, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhyCLtnGE2A

Molyneux, Maxine. “Mobilization without Emancipation? Women’s Interests, the State, and Revolution in Nicaragua.” Feminist Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, 1985, pp. 227-254.

Nabulsi, Karma, and Abdel Razzaq Takriti. “Learn the Revolution.” The Palestinian Revolution, 2016. http://learnpalestine.politics.ox.ac.uk/learn/part/9

Natanel, Katherine. “On Becoming ‘Bad Subjects’: Teaching to Transgress in Neoliberal Education,” In Being an Early Career Feminist Academic: Global Perspectives, Experiences and Challenges, eds. Rachel Thwaites and Amy Pressland. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp. 239-253.

Prashad, Vijay (@vijayprashed). “Anthropologists from the United States and their work for the @CIA or their ideological ties to US imperialism.” Twitter, 14 February 2022, 12:08am. https://twitter.com/vijayprashad/status/1493014216235798529?s=20&t=b-bTnKeve2PW9Fc9Llbfeg

Salih, Arwa. The Stillborn Notebooks of a Woman from the Student-Movement Generation in Egypt, trans. Samah Selim. London: Seagull Books, 2018.

Serpentine Galleries. “Radio Ballads.” Serpentine Galleries, 2022. https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/radio-ballads-exhibition/

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

Zapperi, Giovanna. “Kader Attia: Voices of Resistance.” Afterall, vol. 46, no. 1, 2018, pp. 119–125. https://www.afterall.org/article/kader-attia