Reading Audre Lorde in Palestine: Exploring Differences between Generative and Extractive

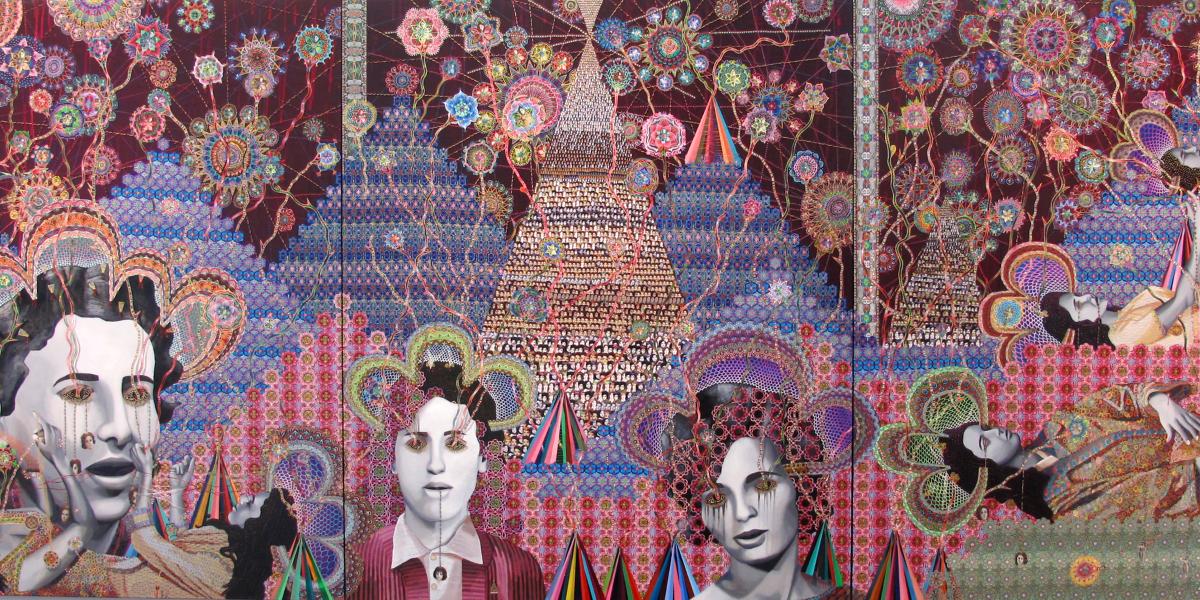

les_femmes_d_alger_acrylic_oil_pins_and_photo_collage_on_canvas_72_inches_x_180_inches_2014.jpg

Les Femmes D'Alger, 2012

I intend this to be an essay about life in Palestine.

Herein, I ask how emotions and emotional thinking, as Audre Lorde teaches, can forge a new sense of future in our ongoing anti-colonial refusal in Palestine. This refusal is and has been grounded in dignity for more than a century of liberation struggles. Rather than speak to the brutality of settler colonialism in Palestine I want to present a challenge, an invitation to think amongst ourselves. The prompt of this essay comes from comrades and the venue is one of substance beyond rhetoric, so this is an opportunity. I shall assume here that the ongoing wars of settler colonialism and zionist desires for Palestinian elimination do not need to be explained – that Palestinian lives and the ongoing vitality of Palestinian peoplehood do not need to be defended. Reflections on life are obviously the makings of a long journey and potentially fabulous story, but by 2022, the contradictions of collective life seemed unbearable as the vast divide between audacious hope and daily reality grew ever deeper. The hope of community seemed to constantly collide with the disappointments inherent in destruction, including self-destruction.

Since these are personal reflections, I should admit that the emotional journey between righteous rage and incomprehensible sadness has been difficult. In a world where “inspirational quotes” take the place of difficult contexts and hard questions, I worry, even in my reflections, that I will reproduce extraction. This is not an academic exercise, but rather an attempt to think aloud in the hope and awareness that I am not thinking alone about how we live in Palestine among the contradictions of life and resistance. The relentlessness and unyielding violence of the past year has been almost unbearable, and I want to be able to talk about feeling lost and confusion without fear. I want to be able to speak to this unspeakable and do so in a location of resistance, community, and love.

The history of colonial capitalism and the brutality of settler colonialism is also a century long legacy of violence against Palestinians, so it is important to read the present – however unbearable it feels – in the context of that ongoing past. It is also part of more than five centuries of refusal of which Palestine is one of many. On 10 May 2021, when the zionist army invaded the holy space of Haram al Sharif in Jerusalem, the brutality of that present resonated: this was, after all, the ongoing Nakba, the 1920s echoing clearly with settlers claiming territory through violence. Living the summer of 2021 and its afterlives has felt like a watershed both in terms of relentless settler colonial violence and internal Palestinian explosions. The conspicuous capitalist consumption of the past decade offered to a certain class of Palestinians provided a false sense of stability, yet also ended up fueling this turmoil. What had been boiling felt like it finally exploded.

In Palestine, the Oslo “peace” accords, imposed on our political context in the 1990s, produced the Palestinian Authority (PA). The so-called Oslo process, then, is part of the ongoing Nakba, one of many attempts to break Palestinian peoplehood and our existence. While part of a larger narrative, the last two decades have been our everyday. Beyond the bloated bureaucracy of non-sovereign entities, even beyond the targeted assassination of the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization), we remain Palestinians with a righteous cause against the injustice of the settler colonial state and those who do its bidding – all singularly concerned with our elimination. The PLO’s transformation into the PA took what once was the hope of a representative entity of a liberation movement and turned it into a structural farce. But we remain beyond all of this, moving through and with our peoplehood.

You need to reach down and touch the things that’s boiling inside of you and make it somehow useful. (Audre Lorde, “A Litany for Survival”)

It is with great hesitation that I approach the need for mythical heroes as a replacement for a lack of love among ourselves for ourselves; this is what I let boil silently inside of me. The rhetoric of resistance has been captured by a discourse that more often than not feels like it floats without grounding. Performance sometimes serves as a replacement for politics and hero-worship displaces our collective sense of responsibilities. Because my anger has been nurtured by the words of Lorde since I first began to learn how to embrace political rage as something generative, I shall continue to rely on her in this reflection. I do not want to remove Lorde from her own social and political contexts as a black lesbian feminist nor should we ever remove her from “her own location,” as described by Adrienne Rich. In other words, I do not want to try to make her Palestinian. I do, however, want her to help me understand where we as Palestinians are in our own locations; I want to show how she helps us think with her.

Reading Lorde in Palestine has helped me transform my own thinking and teaching about who we are into who we can become in the bold hope of doing so together. What is it about speculative conversation that can be instructive about living with Lorde and living in Palestine? Lorde’s words frame, echo, and nurture this piece because I carried her words with me as a method of being.

Lorde helps us read through anger as a useful guide for reflection on the generative and potentially destructive flows of rage. In Arabic, the power of the word ghadab (غضب) holds meaning and connotation for both anger and rage as two parts of a potential spectrum. Reading through Lorde and her thinking, while grounded by the methodological potentials of ghadab, is a journey into and with Palestine. If harnessed in refusal of oppression, ghadab is revolutionary, but if turned in on itself, rage is like a fire that can burn she who holds it. Lorde teaches us that both rage (as ghadab) and love are guides, while fear and vulnerability are realities, and silence is sometimes a tool of the wicked.

Hatred is the fury of those who do not share our goals, and its object is death and destruction. Anger is a grief of distortions between peers, and its object is change. (Audre Lorde, “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism”)

In Palestine, like much of the world, the summer of 2021 was a summer of rage. In the midst of our ongoing refusal, of literal rebellion against settler colonial oppression throughout all of Palestine, we awoke to news of another sort. On 24th June, the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) security forces murdered Nizar Bannat, a vocal critic of the PA and its politics. Repression from the PA as a security apparatus in service of settler colonialism was neither new nor even shocking, but structural violence is systemic, and this felt personal. Through their directed targeting of Bannat and his brutal murder, the captured video of his lifeless body being dragged on the ground, he became an icon. No longer could we try to have conversations about generative versus extractive critique or where our revolution had fallen. Some of us felt that we had to protest and there was no time for nuance. We were on a path towards either an unknown abyss, or a watershed break into a new revolutionary way of being, or both. While the murder of Bannat could have been seen as a moment “out of time,” somehow removed from landscape of refusal, that impression could not hold for long. The confusion of who we fight against was purposefully meant to create a sense of loss that was not intended to be out of time, but rather a moment that stole time through an interruption of refusal. That is, the contradiction meant to create a sense of hopelessness and loss through stolen temporality is actually a classic tactic to derail or somehow purposefully blur anti-colonial refusal. The recipe of how hatred could replace ghadab.

While the violence of the PA is not new in Palestine, for it has long been considered the sub-contracted service for Israel’s settler colonial project, this felt new and utterly devastating – a tactic meant to divide our sense of “us,” and leave us without the responsibility embedded in community. Over the last several years, violence in the service of settler security has taken on an almost singular focus of the PA’s very structural viability, taking precedent over any other services they may provide for a population under occupation. That the murder happened as a clearly intended spectacle in the midst of a spring/summer of what seemed to be a new horizon in Palestinian mobilization against zionist violence from Shaikh Jarrah in Jerusalem to cities and towns throughout Palestine to another war on Gaza, was extraordinary. That it was so lethal to the political body of our peoplehood has more to do with forces above us, but in it, I realized we needed time and patience, neither of which were afforded, to reconstitute hope – collective hope. The outcome of an absurd “peace” process in the 1990s, the PA was the invention of settlers and those who support them. But the people – so many of the actual people working for the PA – were not. The PA is not the government of a sovereign state, even if it claims to be, and even if people often treat it as such. This is a major contradiction in Palestine. Sometimes, seeing beyond the PA and the settler agenda by which it is imprisoned is difficult, but we cannot let it become impossible.

Seeing beyond can also be an opportunity, not only towards seeing beyond the complicity of the PA, but also seeing beyond colonial capitalist structures of sovereignty as defined through the nation-state. Seeing beyond to recover our sense of who we are. The anti-colonial struggle in Palestine can and must challenge outdated goals of recognition. Peoplehood among Palestinians is an active verb that moves beyond the traps of nation-state independence into liberation.

In response to the murder of Bannat, some people, particularly in Ramallah – the seat of whatever power the PA has been afforded by the settler state – took to the streets in protest and the PA “security” apparatus responded with violence and suppression. The intensity of their force was unadulteratedly gendered, deliberately targeting women’s bodies with blunt force. Our bodies became archives of this force, marked quite literally by their blows. Protests these days in Ramallah often feel like performance: we neither confront nor are yet challenged by the settler army. This was not always the case in Ramallah and is rarely or ever the case outside of the city, where the settler army remains a constant presence. This is, after all, an ongoing military occupation and siege. Maybe that is why these protests against the PA felt and were so different?

The rhetoric of unity seems hollow within the storms of all of these contradictions. The violently fragmented geographies of Palestine meant that in 2021, we protested in the spaces we could reach. And Palestinians, acting through our peoplehood, protested everywhere. We could challenge fragmentation through common protest. For me, like many others whose very mobility is limited to small pockets of life, the location of protest was Ramallah by foot and Palestine by heart. But so much of Ramallah is both and at once the home of ridiculous levels of conspicuous consumption and the political engine that drives this stage of colonial capitalism. As spring turned to summer, protests continued, but what changed? Was the space of protest in Ramallah somehow removed from the rest of Palestine? To be clear, the settler army does not adhere to internal boundaries – they ravage Ramallah as they do elsewhere. But in the summer of 2021, might they have considered their violent, material, and constant presence unnecessary to maintain their violence, material, and constant occupation? That the PA as a structure has come to hold the services of settler security as well as the need for capitalist consumption politics is one thing. The people who work for/in/around the PA – that cannot be the same, can it? Have the political parties that participated in the making of the PA, along with the large labyrinth of local and international NGO establishment, captured and occupied our sense of community? Have we all somehow knowingly or unknowingly fallen to the devil’s compromise of bourgeois life over liberation? Even if we succumb to this complicity, even as we register the structural dimensions and constraints of life under settler colonial violence, self-reflection may be the necessary imperative towards recovering our sense of our collective responsibilities. Ghadab cannot exist without class rage. Perfectly manicured hands protesting alone do not carry the generative potential of ghadab.

This kind of notion is a prevalent error among oppressed peoples. It is based upon the false notion that there is only a limited and particular amount of freedom that must be divided up between us, with the largest and juiciest pieces of liberty going as spoils to the victor or the stronger. So instead of joining together to fight for more, we quarrel between ourselves for a larger slice of the one pie. (Audre Lorde, “Scratching the Surface: Some Notes on Barriers to Women and Loving”)

Ramallah is not exceptional. Neither is Palestine. What happened? How did Ramallah become so isolated? How is it that some of the people on the streets protesting seem to let Palestine become a cause without the existential concern of our peoplehood? Politics is always messy; it would not be a mobilization or nurturing community if we did not confront the challenges of our messiness. Why did some of the people around me in these protests, with their perfectly manicured hands, stop struggling with this existential crisis? In each of the moments of the protests, I felt as much alienation as I did community. These protests were not popular; they did not invite masses of people to the streets. Not everyone in protest was the same, but I could not let go of the thought that so few of the hands around me carried the scars of labor or the struggles of poverty or material want. After the 24th of June, I became more obsessed with hands. Maybe I am wrong. Maybe alienation is a self-produced emotion that need not be a general reflection of protest. I actually want to be wrong.

It started to feel like we held more hatred than rage. We turned on ourselves. Those yielding weapons against those protesting are easily hated, but how did we let this happen? Hatred cannot replace ghadab.

As they become known to and accepted by us, our feelings and the honest exploration of them become sanctuaries and spawning grounds for the most radical and daring of ideas. They become a safe-house for that difference so necessary to change and the conceptualization of any meaningful action. (Audre Lorde, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury”)

By the end of these two summers of rage, from 2021 and into 2022, I found myself lost. I fear my own thoughts and even more, find myself horrified by my emotions. What if, by the end of these summers, we lost all the righteousness and were only left with the ugly pontifications of self-righteous? I fear the paralysis of fear that is as much fear of the known as it is fear of the unknown. The one solace I personally have in life – teaching to learn and our ability to talk with a new generation of our warrior community – could this also be lost? Students and teachers at once, the beautiful people I have the honor to know as people and not only as myths of Palestinian resistance and survival, who shall we become if we stop learning from each other? It seemed as if we were just talking at each other; it was as if we had lost our most powerful tool – our conversations. Talking at people and being talked at is the worst kind of silencing, a suffocating silencing. Performance cannot replace community. Hope continues to float, as I know it always will in Palestine, but disappointment feels like a cage that I do not know how to navigate.

The fact that we are here and that I speak these words is an attempt to break that silence and bridge some of the differences between us, for it is not difference which immobilizes us, but silence. And there are so many silences to be broken. (Audre Lorde, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action”)

It was not exactly that we were not talking, but it felt like we no longer knew how to listen or be in conversation. That is a unique kind of silence. Could this crisis somehow lead to us collectively agreeing that we need to re-visit understanding anew? What if we learned how to ask: where do we go now in Palestine as Palestinians rather than telling each other where the other went wrong? Can hope and disappointment find and forge conversation? We are wounded by our hope as much as we are nourished by it. We either suffer through our disappointments together or we give into them alone. The history of Palestine and of Palestinian peoplehood is far bigger than this year and so much bigger than our current sense of loss of conversations. Emancipation and liberation are concepts and ways-of-being that are in dire need of renewal in Palestine. They cannot remain static, nor are they a rhetoric that covers up utter social and economic injustice. If we use this moment to hear and learn, we can break through the rhetoric and journey into and with substance. If we do not, and double down on self-righteous pontifications, where shall we go next?

I know teaching is a survival technique. It is for me and I think it is in general; the only way real learning happens. Because I myself was learning something I needed to continue living. And I was examining it and teaching it at the same time I was learning it. I was teaching it to myself out loud. (An Interview: Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich”)

And so, we travel through confusion and the potential of possibilities and that ever-present hope. We have perhaps lost our sense of “we” – or perhaps we need to consider that it was stolen from us. And this stealing has gone on for so long that we feel a sense of loss without even being sure about what we lost or how and when we became lost through loss. Maybe we misplaced the keen sense and the political logic of our righteous ghadab? Shall we consider why nefarious forces work so hard to steal and who and what they use as cover? If it was easily stolen, it would not be ongoing. And if it was actually completely stolen, we would not continue to learn about ghadab or at least continue to be so angry. If we teach to learn, we write to think. Maybe we are temporarily lost right now so that we do not let ourselves completely turn on ourselves. While our poets who write of heroes also speak of healing from joy and love as a captive state, they continue at least to consider dignity, love, and joy, even if they too are lost. And so, we might continue to both and at once turn on ourselves and celebrate our heroes’ sacrifices – we live these as contradictions and not as complements. Our rage is temporarily directed inward and it is directed, no doubt, by utterly nefarious agendas. This is where we are at now: a living and alive contradiction. If we did not believe in joy or love, our poets would have nothing to compose in the search for heroes. If we do not have anger, we would no longer teach in a need to learn. We have ghadab and it will guide us if we learn how to be guided by it:

Focused with precision it (anger) can become a powerful source of energy serving progress and change. And when I speak of change, I do not mean a simple switch of positions or a temporary lessening of tensions, nor the ability to smile or feel good. I am speaking of a basic and radical alteration in those assumptions underlining our lives…

But anger expressed and translated into action in the service of our vision and our future is a liberating and strengthening act of clarification, for it is in the painful process of this translation that we identify who are our allies with whom we have grave differences, and who are our genuine enemies. (Audre Lorde, “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism”)