When I Am No Longer Here: A Feminist Collaborative Autoethnography of Queer Muslim Death and Burials

A feminist collaborative autoethnography between two queer Muslims in exile, this article raises questions around queer Muslim death, burials and grieving. This is an archive of our secret lives, dreams of queer Islamic burials, and remembering of our near-death moments. We ask; will our loved ones mourn us when we die? Will they give us dignified burials? In asking these questions, we also wonder what secrets we want to bury with us and what secrets we want to unveil with our deaths. We hope that our autoethnographic intervention brings to light the deaths, and afterlives, of those still lurking in and out of family love and intimacies of kinships. This work is dedicated to those of us who are queer, displaced, marginalized, third culture, hiding, surviving, broken, striving, and deeply desiring the traditions and rituals that give us peace of heart, but knowing they aren’t always guaranteed to us or don’t reflect us in our true forms. May engaging in this conversation begin to relieve us of our exhaustions.

Introduction

Queer and trans Muslims at home and in exile move between two distinct oppressions: homophobia and Islamophobia (Rahman 2010; Abraham 2009). Even intimate spaces – the familial home and the queer community – are paradoxical sites. These spaces become sites of love, freedom, kinships, healings, and new lives; at times, they become spaces of oppressions, unbelonging, pain, and death. In our tangled queer Muslim lives, death is as close as the next breath. Therefore, mere survivals become celebrations and archives of our queer lives. Grappling with our survivals, remembering, dreaming, and undreaming, we think of “A Litany of Survival'' by Audre Lorde:

“For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

who love in doorways coming and going

in the hours between dawns

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futures

like bread in our children’s mouths

so their dreams will not reflect

the death of ours;

For those of us

who were imprinted with fear

like a faint line in the center of our foreheads

learning to be afraid with our mother’s milk

for by this weapon

this illusion of some safety to be found

the heavy-footed hoped to silence us

For all of us

this instant and this triumph

We were never meant to survive.

And when the sun rises we are afraid

it might not remain

when the sun sets we are afraid

it might not rise in the morning

when our stomachs are full we are afraid

of indigestion

when our stomachs are empty we are afraid

we may never eat again

when we are loved we are afraid

love will vanish

when we are alone we are afraid

love will never return

and when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

nor welcomed

but when we are silent

we are still afraid

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.”

We have been afraid for so long. We have been afraid about our secret lives – the lives we were meant to live. We have been afraid about losing our loved ones to the violence of Islamophobia, racism, displacements, and war. We have been afraid that our queerness will kill them. So we have remained silent all along. Now we are here to speak. We are here to speak of our secrets, haram loves, sacred dreams, and living deaths. We are here to speak back to the powers that try to keep us silent. We are here to speak to the remaining survivors and to those after us. We are here to remember the queer us.

We (Qais and Wazina) were connected to one another through our separate participation in the annual LGBTQI Muslim Retreat. This convening was one of the few, if not only, of its type in the United States, that offered a safe space for queer and trans Muslims to gather, heal, return to faith, recreate new traditions, and connect with one another. Afghans meeting other Afghans in such spaces was more than rarity – it never happened – both for us and our queer Muslim friends who immediately encouraged us to meet.

Growing up in the United States, building a friendship in trust with Afghans has never been easy for me (Wazina). From childhood through early teen years I was discouraged from making any friends other than my (Afghan) cousins out of the fear that I would be too “Americanized.” When puberty set in, my mother and her sisters began to instill competition and distrust in us, their daughters, and our friendship was rewired. We were now banished from sharing any secrets or confidential information that could bring shame to us or more importantly, make our mothers look bad. As a teenager with a very loaded secret, I internalized this shame and began self-isolating from Afghans out of fear of gossip or worse.

As an out Afghan with public-facing work, many often reach out and share their journey, the relief that they aren’t the only one, and my role is somewhere between queer Afghan elder and counselor. Connecting with Qais was a bit different than encounters with LGBTQI Afghans raised in the United States.

Currently based in the United States, I (Qais) was born and raised in Afghanistan and lived as a refugee in Pakistan during my teenage years. Making friends, falling in love, and holding grounds were not what we could afford as a people on the run. My mother always told me – mahajer asti, dileta ba kas wo ba makan e basta nako. Dilet mishkena. “You are a refugee. Do not tie your heart to a person or a place. Your heart will be broken.” But I couldn’t hold back my queer heart. I had it broken by those I loved in secret and those I trusted with my secrets.

We (Qais and Wazina) share in the understanding of Afghan gossip culture and the pressure to cover any part of us that could discredit or shame our families. We both trust each other with our secrets and share the queer Afghan kinship with love and care. We are both in our mid-30s and living out our complex queerness, dreaming, healing, mourning, and writing collaboratively.

This feminist collaborative autoethnography between us is an archive of survivals, near-death moments, celebrations of our queer lives, anticipatory grieving of our deaths, and dreams of having queer Muslim burials. This is our way of speaking to be remembered, as Audre Lorde calls upon us. We speak so that our desires for the afterlife are not erased like our queer childhoods or teen crushes. We speak so that our demands for dignified queer Islamic burials are not denied like those wishes for queer freedoms in our lives. We, Qais and Wazina, question if our families and loved ones will grieve us as they imagined us to be or who we actually were when we are no longer here. Are our lives even “regarded as grievable” (Butler 2016, 129)? We wonder what secrets we want to bury with us and which ones we want to or can set free and bury for our living.

As we write this article collectively, a pandemic has affected millions of lives around the world, particularly in the Global South, and particularly those of queer, trans, black, indigenous people of color, women, and poor people (Gato et al. 2021; Iyanda et al. 2021; Al-Ali 2020; Bassily 2020). The promise of a new United States administration continues to incite the actions of white supremacists targeting minoritized communities and racialized groups, including Muslim-Americans. There is also a war back in Afghanistan, a place we both call home and yearn to return to. Roadside bombs, suicide bombings and targeted killings are daily happenings as the international community has exited Afghanistan deeming their security mission complete, handing over the country to Taliban, a group once labeled as terrorist. People are too fearful to stay and too scared to leave. With the perpetual presence of violence and war within and around us, we can’t help ourselves but think of death, now more than ever. In every suicide bombing back home and in every Covid-19 death here and there, we wonder how many queer and trans Muslims; those in the closet, those out, and those lurking in the in-betweens, died. In remembering loss of queer and trans Muslim lives, at home and in the diasporas, we shed light on the unlived desires, incomplete dreams, and clandestine lives that reveal themselves after death. Can we ever fully be who we are before death? How will we be remembered? What can we choose to reveal after we are gone?

Methodology

In this article, we utilize feminist collaborative autoethnography (Chang, Ngunjiri, and Hernandez 2016). This approach allows us to combine our similar yet also different queer takes on the gendered and sexed traditions, rituals, and anticipations of our death and the afterlife, while collectively thinking, dreaming, and healing. Our collaborative work here emerged as part of our continued conversations and the immanent struggles in navigating racialized, gendered, sexed, Islamophobic and homophobic spaces. In this collaboration, we self-reflect on our individual and unique identities and lived experiences – autoethnography, yet come together and process them collectively – collaborative autoethnography.

Autoethnography combines ethnography with autobiography (Pace 2012). It is a form of narrative that situates the self in social context (Ellis 2004). Autoethnography serves as a link between the personal and socio-political. As a methodology, it provides a venue for lived-experiences to give meaning and purpose to abstract concepts and theories. We employ this methodology in order to move between time, borders, and spaces, and connect the personal with the political and social. Through reflections of the self and its experiences, autoethnography weaves the individual with the system and structures. It carries the hope of shedding a clearer light on the complexities of being, living, and politicizing the queer and trans Muslim death and burials in geographies with history and legacy of colonialism, patriarchy, racism, interventions, and war. Haneen Ghabra calls this connecting self with the broader structures “speaking back to the system” (2015, 3). We here aim to speak back to those systems and structures that deny our queer and trans bodies burials and our queer and trans lives dignified deaths. We also speak to our remaining survivors who share similar dreaming. Our approach is also informed by feminist poetics and politics of autoethnography that allow for “the explicit reflection on one’s personal experience to break outside the circle of conventional social science and confront, court and coax that aching pain or haunting memory that one does not understand about one’s experience” (Allen and Piercy 2005, 158). This article reflects on haunting memories of our near-death moments, painful remembering of our conversations, and hearings of our families questioning our lives and deaths. In doing so, we trouble the gendered/sexed dead bodies and Islamic burial and mourning rituals at home and in exile.

We are aware that autoethnography exposes our vulnerabilities. We politically and lovingly “embrace [our] vulnerability with a purpose” (Jones 2016, 136). As Onowa McIvor emphasizes, autoethnography is “an open invitation to judgment and scrutiny. One hopes that through sharing some of one’s intimate details, it also opens possibilities of compassion, kindness and greater levels of understanding” (2010, 33). We hope that by sharing our intimate details and vulnerable moments in the pages of this article we are able to open up discussions and conversations on queer and trans Muslim lives, deaths, burials, and grieving. In the naked exposure of our near-death experiences, fear of nobody mourning us, and dreams of a queer Muslim burial, we intend to offer alternative ways to observe death and burial rituals in the lives of those Muslims who defy gender binaries and sexed bodies.

Who is going to bury? – Wazina

The first time my mom, madar jaan, got sight of my tattoos she said to me:

What will they say when they wash your body when you die? Your secret will be visible for everyone to see. What value does it have to create a life that spends all its energies hiding – I can’t imagine how exhausted you are.

It’s true, I am exhausted.

I don’t believe that I am the only one hiding more than tattoos, covering, performing, waiting for something significantly better to happen and we all are exhausted, even you, madar jaan. I can’t even begin to imagine the relief that can come when I don’t have to.

When I rejected a suitor for marriage she pleaded with me:

Wazina, who is going to bury you?

I wonder how often she thinks about this for herself. Does she wonder if I am capable of executing her wishes when the time comes? If I refuse the tradition of being tethered to a husband, will I be able to fulfill our burial rites or fulfill upon my own rites?

After graduating from college, I did everything in my power to avoid moving back home with my family including securing a stable job and lying about pursuing grad school. Initially I told my parents I was living with “my friend” and began to slowly release hints and hard truths that she was more than that, and that I had no intention of returning home officially.

Somewhere between 22 and 23 years old, I remember my mother pushing back on what I was doing and why I wasn’t returning home to them. Exasperated and out of ideas she said to me:

What am I supposed to tell people about where you are? How am I able to face them when my eldest daughter doesn’t live at home?! I should just tell them you are gone, have a funeral for you, and never have to be asked about you again.

I wondered how many others this had been done to and if I would really join them as the undead.

When asked about my coming out, I think most people are pretty disappointed by my answers because I don’t give the ones they expect to hear – I am not refraining from indulging them either. My internal processing was genuinely easeful:

I have a sexual desire for girls therefore I am not like the other girls in my family, Allah knows this, because Allah made me.

Growing up in silence around sexuality, whether gay, heterosexual, or otherwise, I assumed this part of us would never be given space to live.

When I made a choice to tell them I was in a relationship with a woman, it stung in a very different way because it affirmed exactly what I had expected but hoped to avoid: shame and dishonor. Baba took it upon himself to damage control and rationalize this impossibility. In a car ride together, he told me with every ounce of his being that there was no such thing as gay or lesbian Afghans. If you think you can be public about this, then you need to know ba kafanem shash wo go mehkohnan/they will piss and shit in my coffin.

Khalas. That’s it. How could I even consider living in a way that would compromise all of my father’s living, death, and afterlife? This was the grave I dug for myself and I would have to lay in it.

Avoiding hard conversations, dismissing individual truths for the good of the collective, and living in secret, is what I was taught and have mastered. When I came to find the words to name myself as queer, it offered bittersweet relief because I now had a language of my own. I knew that I’d take this dirty-to-everyone-else secret to the grave with me and when my uncles exposed me after an internet search, I knew it was my own fault for bringing this shame to light. It was my fault and I deserved the cold shoulder and withholding of affection from Madar and Baba. It was my pride and selfishness that had this made this bed and I had to lay in it.

My Baba wished I was dead – Qais

I haven’t stopped thinking about my death since I heard my Baba wishing I was dead.

Did he wish death upon me when he first held me

right out of my mother

a woman that had already given life to

six others?

They say it isn’t easy to raise one

let alone seven

in the midst of a war

and a famine.

They said if they could afford milk for me

they couldn’t afford sugar.

And I wouldn’t take milk with no sugar.

I cried like I knew I was born in the

wrong place

wrong time

Afghanistan

The Cold War

You called it the Cold War

When I felt its fire burning me down inside my mother’s womb

I didn’t want to come out

Overdue

Or dead?

They contemplated.

They say I took ten months.

But now I wonder who keeps track of time

In the midst of a war?

I wonder

Did he wish death upon me when he named me after a lover?

Or when he realized I was nothing like his two other sons?

I remember the moment my father wished death upon me very vividly. Among many things that I wish to forget, this stands on the top of my list. It was a beautiful spring Friday in Kabul. We were getting ready for my cousin’s wedding which was happening in the evening. My two sisters and three cousins asked me to teach them how to dance. My love for dance and up-to-date Bollywood moves had given me a free pass to find myself in women-only-spaces during wedding parties and family gatherings without much trouble. I was showing my sisters and cousins my favorite dance moves those days, which was placing the right hand on the heart and left hand stretched up the shoulder and bringing it back down slowly coordinating it with the beat. The room was filled with joy, laughter, and loud Bollywood music until my Baba jumped up and switched off the tape recorder. A sudden silence engulfed the room.

It was so silent that one could hear the breeze blowing in through the cracks of windows half blown by rockets and bombs. I could hear the ripped tape hitting the broken glass window as the wind made its way into the room dancing with the fog of tea steaming out of my aunt’s cup. My favorite aunt, Salima, who was the only other reluctant audience member to our dance in addition to Baba, asked my Baba, “what did you do so wrong with Qais that he turned out so feminine, like this?” pointing at me with her hand scanning my body up and down from afar. My Baba responded, “I wish Qais was dead.”

I was 21 years old and full of life. At that exact moment, I felt life exiting my body and leaving the room through the cracks of the window and into the breeze outside. It felt what Eric Stanley calls “death-in-waiting” (2011, 1). Since then I have been waiting for my father's prayer to be accepted. I have been waiting for the death he wished upon me. Since then I have curated my funeral and burial in my head over and over. There are days that I imagine my funeral as big as an Afghan wedding for I will never have one. I want my lovers to be there. I want those who rejected me to be there. I want men who desired me behind closed doors to be there. I want my aunt and dad to be there. Sometimes in those imaginations, I deny my Baba and my favorite aunt Salima to farewell me. Other times, I dream about my Baba and my favorite aunt holding my feminine queer body wrapped in pink and green kafan in their arms, grieving me like they loved all of me.

Queer Muslim Death at Home and in Exile: Witnessing, Living

Queer and trans lives are constructed as threats to safety, security, and heteropatriarchal structures (Ritcher-Montpetit 2017; Amar 2013). From state intimacies to familial kinships and public spaces, queer and trans bodies are perceived as dangerous at times, while at the same time as nothing or insignificant (Stanley 2011). This hypervisibility yet invisibility of our existence is entangled with perpetual violence. My queerness allowed me (Qais) to dance in women-only spaces where men were strictly forbidden because I was nothing to the men guarding those spaces. Yet, I became hypervisible when I danced in men-only spaces, a danger to their masculinities. Some mocked me while others showered me with money and touched me when they found an opportunity. In both women-only and men-only spaces, when I danced, I was scared someone would attack, kill, or rip me apart, like they did with Hayat, the trans person whose body was found in a rice bag outside the wedding hall that stood across our house on a crowded street in Kabul. One early summer morning in 2004, words spread like wildfire in the neighborhood that a dead body was discovered by an old man who was headed to the mosque for morning prayers.

The wedding halls were few in numbers. Thus, they were always packed with two-three wedding parties at the same time on different floors. This was only three years after the fall of the Taliban. Young Afghans were excited for the future and hence they threw extravagant weddings that they weren’t allowed during the Taliban regime from 1996-2001. As the early dawn light was covering Kabul’s sky, we all gathered on the street as the police came to investigate the body in the rice bag. The word was out that inside the bag there wasn’t a woman but an izak, a derogatory term referred to a trans person or a feminine homosexual man. The crowd surrounding the five police officers and the bag was getting bigger as they removed the body from the bag. The body was chopped; a hand and a leg were missing, but the torso still had a dress on. The police were asking the crowd if anyone had seen any legs or hands nearby. They were trying to figure out whose body it was and where it came from. Someone from the crowd suggested that because the mosque was only a few houses down and the imam knew almost everyone in the neighborhood, they should ask the imam. Therefore, one police officer went to the mosque to ask for the imam to come and identify the body. When the imam arrived, he immediately recognized the dead person in the bag, and told the crowd – yak insan e gomrah bod- da libas e zanana mairaqseed. Namish Hayat bod. “The person was a transgressor from the right path and was dancing while dressed in women’s clothes. His name was Hayat.”

Hayat means life in Farsi.

Life is short for those of us living at the margins of oppressions at home and in exile. In Reflections on Exile, Edward Said writes, “exile is strangely compelling to think about but terrible to experience. It is the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home: its essential sadness can never be surmounted” (2000, 180). Now living in exile, we know what Said meant by exile as a terrible experience. Some of us escaped wars and homophobic violence at home only to be caught in the homophobic and Islamophobic violence in exile. Some of us are living a slow death while longing for return. Some of us are killed by the forces of exile.

The exile we (Qais and Wazina) live killed Sarah Hegazi, another queer refugee like us. We mourned Sarah’s death in the middle of a pandemic in isolation. Sarah was forced out of Egypt into Canada. There, in exile, the violence of the past and pain of a stranger land killed her. For some of us who come from the south and who are queer, Muslim, broken, and rejected, exile is so terrible that even death becomes “strangely compelling” (Said 2000, 180).

We Die Young

When our younger selves looked to the future, we only pictured a version living to maybe 25 years of age, our life expectancies cut short by war and or by its circumstances. Without any way of envisioning a version of our future Qais or Wazina who made it, we did not exist, even in our imaginations. There were no role models for those like us who embodied identities we knew ourselves to host, and certainly not those who were talked about in a positive light (or ever named). We accepted that we would be dead one way or another. We envisioned ourselves as the undead: even if we were to live beyond 25, we would compromise our living by killing off dreams of a fully self-expressed existence, so death in any form was both truth and necessary. It would be our naseeb or fate.

As queer kids growing up on the heels of the AIDS crisis, war, and rise in xenophobia in Afghanistan, New York City and Pakistan, we continued to inherit the concept of early death. Because so much of our sexual identity was defined through the white orientalist gaze, our queer existences became threats to the heteropatriarchal state and home. At home and outside of the home, our queerness was developed with the input and narratives of the white western gay movement that was a monolith we didn’t quite understand just yet. These narratives continue to offer us worst case scenarios and life outcomes: being found out and killed by our families, rejection, bullying, death by homophobia (by lover or community), loneliness or drugs and alcohol. We wondered who would kill us first? A lover? A family member? Or ourselves?

In 2004, I (Wazina) began my career as a sexual health educator during a time when there was great public concern and urgency to take action to support LGBTQ youth in the United States. I was brought in as an expert in these efforts, supporting the creation of safe spaces and student clubs such as Gay & Straight Alliances, and curricula that was both representative and affirming of queer and trans youth. In my personal life, queer and trans women I knew of and was socially adjacent to were taking their lives, triggering disbelief in my queer community. Embarrassingly, the truth was that none of this fazed me; I completely understood the necessity for this way out. Hoping for and imagining a normal or dignified dying is nearly impossible when we hold identities that are never granted dignity daily. Regardless of the school culture stopgaps we offer, this would be inevitable for some of us. Suicide was a last ditch promise to myself and remains at the bottom in my toolkit for survival.

I (Qais) have gotten very close to death a few times in my life. When I was lying in bed in the hospital in Minneapolis after a heart attack in 2013, I called my mom but couldn’t tell her that I had just came out of death and that my lover was sitting by my bedside. She heard my shaky voice and asked me when I would be home next – I didn’t have the answer to her and I still don’t have that answer to her. I was undocumented back then and far too deep into my queerness now – will she even recognize me? Will she wish death upon me like my Baba did?

Death was always around me growing up in Afghanistan and Pakistan in the midst of a war and displacement. Death is in my father’s wishes for me. Death is in my nightmares. Death is in my thoughts every time I bed men – will they kill me after they make love to me? Will I burn in hell for making haram love? I don’t know what men have on their mind when they fuck me but I have death on mine.

Will my family have a funeral for me like they did for my cousin whose head was blown away during a suicide attack? Will they bury me in our family graveyard in Shamali, next to my aunt, Salima who agreed with my dad wishing me dead? Now I tell my lover to ship my body to Afghanistan – where I first fell in love, where I first wished for death, where I first attempted to committee suicide, where I was first assaulted for being too feminine at age six. That’s where I want to be buried. I tell my lover to tell my family my secrets but not all of them. Will my siblings come to visit my grave every Eid and shab e barat? Will aunties stop gossiping about my sexuality after my death?

The Secrets We Leave behind, the Secrets We Bury with Us

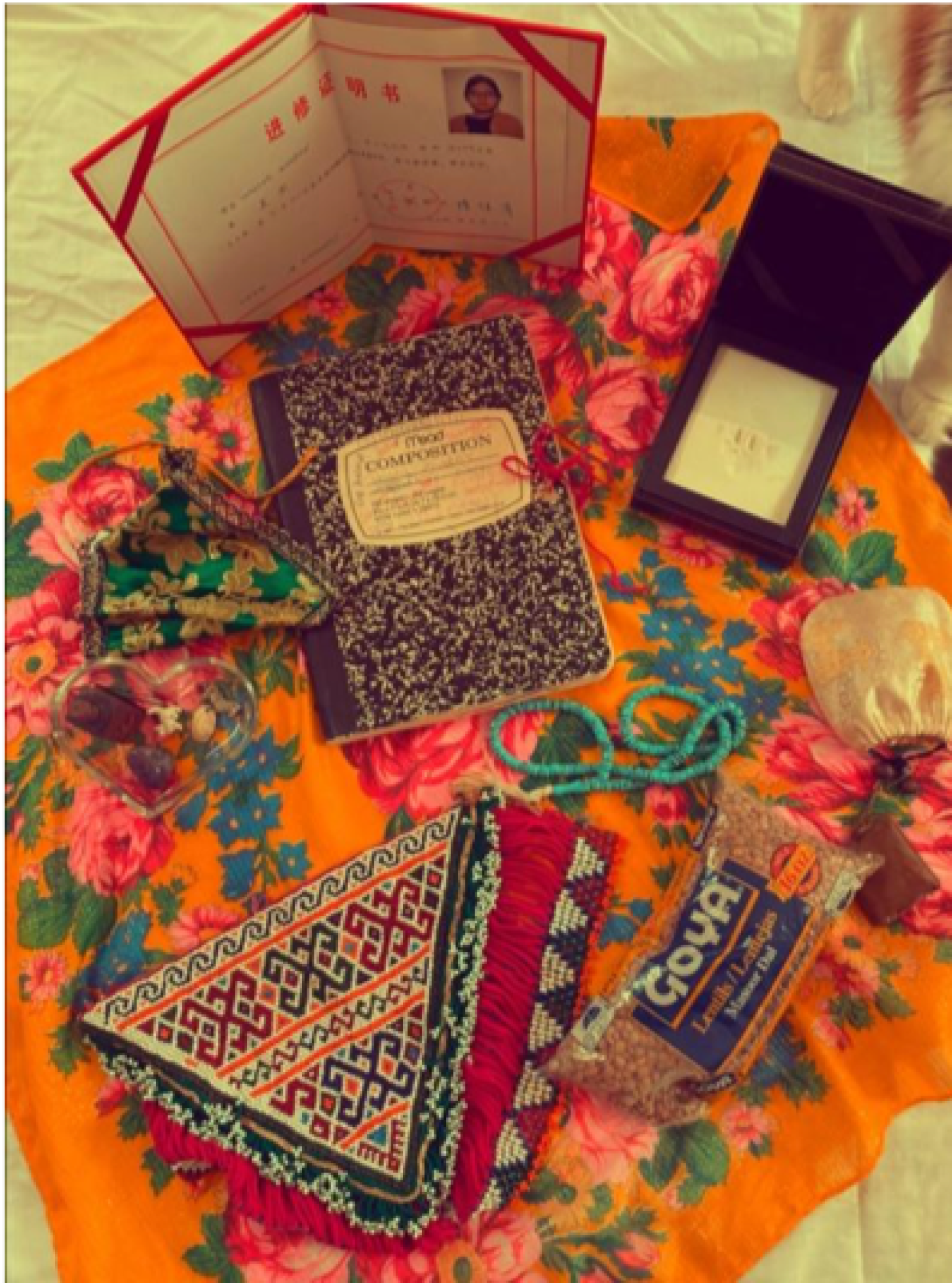

The tradition of preparing one’s suitcase for death has captured our attention since we were young, fascinated by the morbidity, the care and preparation, filling it with what is needed for a Muslim burial and extra touches. It becomes clear that these were not created in times of sickness: they were steadily and carefully curated way before. Each held practical tools for preparation: shrouds, soaps, combs, duas, rose water – the small reminders of their former vanity. The suitcases we witnessed growing up were also of those living in heterosexual binaries. What would a queer Muslim suitcase for death contain? We imagine a slow evolution from selfish and selfless, knowing this tradition is a service for both the living and now deceased, moving towards the embrace of peace. Our suitcases are also symbolic representations of the secrets we leave behind, the secrets we let unveil after we die, and the secrets we bury with us.

The indelible curation of these suitcases also begs the questions we’ve never been able to ask our loved ones:

Were you stoic in preparation or did you shake and cry placing them in the suitcase?

When did you know to tell someone where it was tucked away?

How often did you revisit the contents?

And most of all, did this give you peace of mind and heart for both your living and dying?

What would I put in mine? – Wazina

Madar’s words about my tattoos stay with me like new ink, reminding me of my secrets coming to the surface – and they have over and over in family members’ attempts to socially kill me. My queerness, my falling short of traditional milestones, and my inability to perform zaan/woman properly are constant reminders. I wonder, what is the difference between a life of secrets and lies? If I have made it this far, well past 25 years old with no path to traverse, living through the violence of family, lover, and state: can I release the secrets now?

- A bag of beans to encourage or remind the preparers of my body that I am Muslim. I don’t know what the first days in the grave will be like but I hear they will be disorienting and scary and I ask that they do a khatem for me. As many thousands as you can muster.

- My journal as a child.

- The imprint of Jack’s paw: he was my companion and beloved for 12 years, gifting me the longest and healthiest expression of love I’ve ever known.

- Mementos from travels in the form of seashells, stones, and souvenirs of my time traveling abroad to China and Mongolia. At 16 it was the first time I was so close to home in Afghanistan and so homesick for my family.

- The duas, taweez, prayers, and spells that were meant to protect, keep, and/or return me to the right path. I entrust they ran their course and did their part regardless of what others think.

- A heena-paych,henna wrap. Henna is one of my most favorite expressions of culture, having taken me so long to pummel through self-hatred and bullying to own it. I love how it’s existed before me and will live on after me. Madar collects these wraps from the weddings she attends hoping they will bring good luck for her daughters. I may never be married or in the way she wants; I do not want her to grieve that but know that I held her hopes front and center of me, even when it looked otherwise.

- My funeral shrouds or kafan.

What do I want to leave behind? – Qais

Living in war in Afghanistan, I got used to carrying a few sentimental items with me in my backpack – what if I die in a suicide bombing? How will my loved ones find me? In Kabul, we carry written addresses and telephone numbers of our loved ones in our pockets or backpacks just in case our luck gives up that day and we are blown off by a roadside bomb or in a suicide bombing. I packed my suitcase with some of the items that resemble those I carry in my backpack.

- A family photo that was taken in the midst of war in Kabul right before my family escaped to Pakistan. This is the only family photo that has remained – all others were burnt or lost during the war.

- A collection of my poems in Farsi that is now the archive of my feelings at a time when I was struggling with my sexuality; naming and expressing my desires for life and death.

- A silhouette of love.

- A box that carries a rope that my Baba tied around my suitcase when I last left Afghanistan for the United States. The rope was to help me not lose my suitcase. I didn’t lose my suitcase but I lost everything else.

- The heels I wore as I walked on the stage to receive my Ph.D. degree.

- A notebook that carries my home address, telephone numbers of my loved ones, and my Afghan passport.

- A headless chicken, gift of a dear friend for a special occasion.

- My pink and green floral kafan – something I always wanted to wear for my wedding.

Conclusion

We hope that our autoethnographic intervention brings to light the deaths, and afterlives, of those still lurking in and out of family love and intimacies of kinships. We are neither disowned nor rejected yet but that could happen in death and afterlife when all is revealed – when the secrets we hold in our bodies are unveiled. This feminist queer collaboration became a mode of survival for us during a pandemic and isolation of a lockdown. While the world publicly mourned the loss of loved ones and normalcy, there was a familiarity to the loss that surrounded us. The privilege of public grieving was not something we could afford prior to the pandemic. We grieved and mourned the loss of our queer and trans siblings in secret just like we loved them in secret. Some of us, abandoned by our families in life, wonder if they would abandon us when we die. Having religious privileges and legal rights over our bodies (Zengin 2019), we wonder if our families would find us worthy of grieving, hold funerals for us, and grant us the Islamic burials that we dreamed of.

This article is part of our larger interdisciplinary project titled When I am no longer here: Queer and Trans Muslim Death and Burials at Home and Exile dedicated to those of us who are queer, displaced, marginalized, third culture, hiding, surviving, broken, striving, and deeply desiring the traditions and rituals that give us peace of heart, but knowing they aren’t always guaranteed to us or don’t reflect us in our true forms. May engaging in this conversation begin to relieve us of our exhaustions.

Abraham, Ibrahim. "‘Out to get us’: queer Muslims and the clash of sexual civilizations in Australia." Contemporary Islam 3, no. 1 (2009): 79-97.

Al-Ali, Nadje. "Covid-19 and feminism in the Global South: Challenges, initiatives and dilemmas." European Journal of Women's Studies 27, no. 4 (2020): 333-347.

Allen, Katherine R., and Fred P. Piercy. "Feminist autoethnography." Research methods in family therapy 2 (2005): 155-169.

Amar, Paul. The security archipelago. Duke University Press, 2013.

Bassily, Nelly. “Leah Lakshmi Taught Me: my anxious, pandemic-time musings about building for the long-haul”. Kohl: a Journal for Body and gender Research 6, no. 2 (2020): 183-186. Available at: https://kohljournal.press/leah-lakshmi-taught-me

Butler, Judith. Frames of war: When is life grievable?. Verso Books, 2016. 129.

Chang, Heewon, Faith Ngunjiri, and Kathy-Ann C. Hernandez. Collaborative autoethnography. Routledge, 2016.

Ellis, Carolyn. The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. Rowman Altamira, 2004.

Gato, Jorge, Jaime Barrientos, Fiona Tasker, Marina Miscioscia, Elder Cerqueira-Santos, Anna Malmquist, Daniel Seabra et al. "Psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health among LGBTQ+ young adults: a cross-cultural comparison across six nations." Journal of Homosexuality 68, no. 4 (2021): 612-630.

Ghabra, Haneen. "Disrupting privileged and oppressed spaces: Reflecting ethically on my Arabness through feminist autoethnography." Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research 14, no. 1 (2015): 2.

Griffin, Ada Gay, and Michelle Parkerson. A litany for survival: the life and work of Audre Lorde. New York, NY: Third World Newsreel, 1996.

Holman Jones, Stacy. "Living bodies of thought: The “critical” in critical autoethnography." Qualitative Inquiry 22, no. 4 (2016): 228-237.

Iyanda, Ayodeji E., Kwadwo A. Boakye, Yongmei Lu, and Joseph R. Oppong. "Racial/Ethnic Heterogeneity and Rural-Urban Disparity of COVID-19 Case Fatality Ratio in the USA: a Negative Binomial and GIS-Based Analysis." Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities (2021): 1-14.

McIvor, Onowa. "I am my subject: Blending Indigenous research methodology and autoethnography through integrity-based, spirit-based research." Canadian Journal of Native Education 33, no. 1 (2010): 137-155.

Pace, Steven. "Writing the self into research: Using grounded theory analytic strategies in autoethnography." Text Journal, no. 13 (2012).

Rahman, Momin. "Queer as intersectionality: Theorizing gay Muslim identities." Sociology 44, no. 5 (2010): 944-961.

Richter-Montpetit, Melanie. "Everything you always wanted to know about sex (in IR) but were afraid to ask: The ‘queer turn’in international relations." Millennium 46, no. 2 (2018): 220-240.

Said, Edward. "Reflections on exile." Said EW Reflections on exile and other essays. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, 2000. 180.

Stanley, Eric. "Near Life, Queer DeathOverkill and Ontological Capture." Social Text 29, no. 2 (2011): 1-19.

Zengin, Aslı. "The Afterlife of Gender: Sovereignty, Intimacy and Muslim Funerals of Transgender People in Turkey." Cultural Anthropology 34, no. 1 (2019): 78-102.