Circling: a Methodology

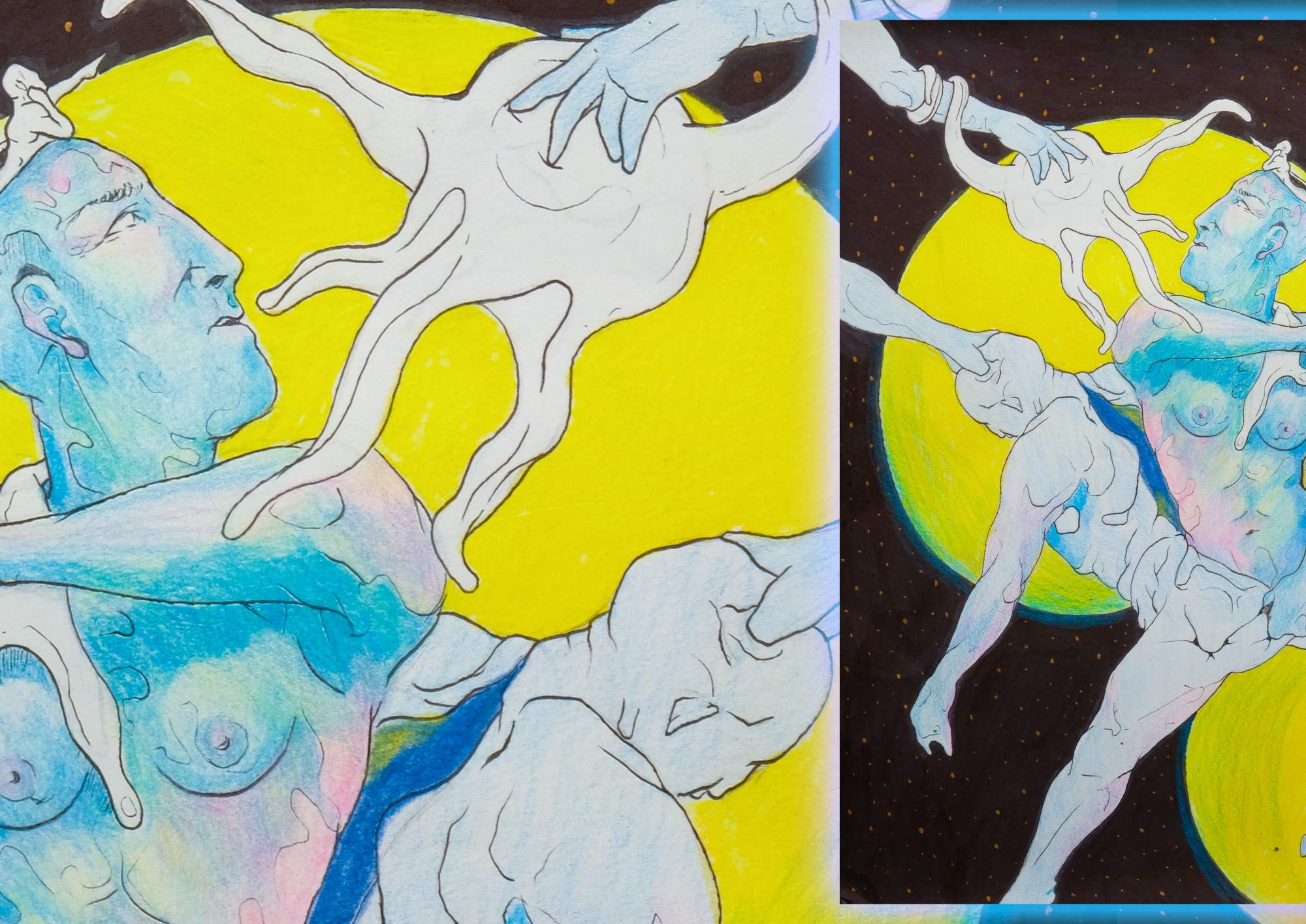

theod1_copy.jpg

star shedding its skin

This issue, in line with Kohl’s trajectory/ies, is a labour of political love. It finds solace, commitment, and determination in the undergrounds and cross-Oceanic rhizomes of friendships that defy conventional borders, visa applications, and our present time.

Time, although long commodified and fashioned to support global economies that demand a minimal commitment of 8 hours per day, 5 days per week, 52 weeks of the year, only for our efforts to evaporate in a sea of taxes, debts, and recycled capitals is, on our side.

A moment in time, whilst looking fleeting on the surface, is never lost. When the clock ticks a second forward in Beirut, a friend, somewhere in Palestine, in Cairo, in London, in Quito or in Lahore relives the moment. Every tick scatters our noes across the world. We say no to “coming out” and to TERFS. Our closets are not closeted per se. We question statements of “authenticity” and embrace denormalizing instead. We rewrite campiness as inherited imaginary. We recognize in young migrant men’s suicides a subversion of patriarchal constructions of masculine resilience. Our friends are our family – bones, blood, and all. We understand transing as intellectual, geographical, and bodily crossing. We reprogram our futures by recoding grief.

When we gathered in an OK hotel in Beirut almost a year to the date of writing this editorial, little did we know about the days to come. COVID-19 aside, Beirut suffered the mother of all explosions, or so they say, in August 2020. Many of our accomplices, who have long sought to uphold Kohl’s residency in our beloved city, soon found themselves scattered across the globe.

I read you, Sabiha, and I wonder, whom are we writing this editorial for? What are we making ourselves legible to? 6 years of Kohl’s history sit with me, and time, and space, both seem to merge their timelines. You are a square on the top right corner of my screen, with your Edwardian haircut and your fish aquarium, and I have to believe you are somewhere in Falmouth, UK. I am propped up on an “ergonomic” chair in, I am told, a Parisian suburb. I think of my sisters in Beirut, and I can imagine their lives with such vivid intensity, from the coffee smoking on the stove, to the sound of the doors welcoming me in, to the density of the light on their balconies, that it is like I have never left. And in a way, I/we haven’t; we keep going back to these moments like lifelines, glimmers that tether us to our political existences. And we hope that the cartography of them would be powerful enough to overcome traumas, collective and passed on, until we realize that mapping lifelines is a work of trauma.

This issue could have been the first of Kohl’s. I even ask myself, why wasn’t it the first? We still had the capacity for joy, so we raged at the world and its means of production like we could change them. But in many ways, too, it feels like the completion of a political vision, tracing lifelines against traumas, again. This issue embodies queer feminisms not because of its tangible format, but because of the spaces and times that haunt it. It was Beirut in November/December 2019, and we came so close to changing the world, sputtering spells inwards and outwards, in the streets, and in the conference room of a hotel overlooking the industrial areas of the port.

It is perhaps our queer sixth sense, a special mode of knowing of things to come, which brought us together during the last month of a pre-COVID normal that we certainly do not long for. We gathered in a hotel in Beirut almost on the eve of waves of lockdowns, grounded airplanes, deserted streets, and anxious politicians to come.

We almost postponed that workshop. Technically, we were on strike, adhering to the revolutionary demands. But we had never been an “institution” in the proper, governmental sense of the word – we had always threaded on the margins of respectability. Our workshop, in a sense, was disruptive of the status quo. So we held it anyway.

Over 5 days, we worked the ins and outs of queer subjectivity/ies. We felt love. We were the love. As Sarona says, “we were the moment.”

We created the meeting table we had been longing for at gatherings organized by others, because we realized that if someone had to make it happen, it was us. For those of us who stayed behind, in Beirut, we unknowingly mourned that meeting table every time we queued in front of banks and supermarkets and gas stations. Our neoliberal economies are a scam, and when we demanded the fall of the system, we knew, even if we did not say it to each other, that we would pay the price. Before a system falls, it sucks us dry and closes in on us in its vicious attempts at survival. So we scatter, like we did on August 4. But at that workshop, we were the moment; everything before was conducive to it, and everything after can bring us back to it, over and over again. In our elation, we forgot, for a few precious moments, that time is a cycle and we are the tide.

We have archived our workshop and additional contributions in our Queer Feminisms issue. Theorizing, coding, indexing, wandering, historicizing, rediscovering, and tentative writing are the means of production through which we archive our body/ies. These means are the blocks upon which we structure our issue. We neither distinguish nor question the value of a commentary, when juxtaposed against a theoretical text. We rediscover our region as we have come to experience it throughout our childhood, teenage years, and later years. There is a mutuality between us and our region. Like Ahmad’s closet, we find validation in the violent spaces our region procures: the street, the family, the gossipy neighbours, our bedroom, and the state’s edifices. Our region informs our writing. It is not a passive receptor of high theory/ies waiting for their application.

Most importantly, this particular issue, for many of us, epitomizes the very trajectories of Kohl: we recuperate lost stories, comfort isolating bodies, and ponder a future that fuels our queer radical imaginaries. We build a universe of our own where we decentre states and patriarchs. We trial the limits of hope against reason and rationales.

With this issue, we come full circle. We wanted to

demystify the centrality of Europe, to ask who or what made it the centre of the universe, the centre of our school curricula, of our modes of governance and kinships, of our currency/ies, our palates, and the trees and grains we chose to grow. If whiteness is understood as a hegemonizing mode of being, seeing, and feeling in the world following strict Eurocentric definitions of progress and mass-consumption, oftentimes under the guise of the neocolonial discourse of development, there is little doubt, then, that it has appropriated every space, crack, fissure, and resource.

But we no longer want to engage with the trap of whiteness as the origin, the generator, the pioneer, and us, the peripheries, the minions, the late-to-the-game. We carry our histories in our bodies. Yet, we resist entertaining the ghost of a white Europe, even as it sits on our tables uninvited.

And so, with this issue, we come full circle. We wanted to seize the means of production to theorize our queer lives; we wanted to make them “real” by making them visible, by leaving a trace, so we chased traces left for us across times and spaces. We read about other struggles in other times and places, and we longed for and mourned our queer South genealogies as if we could no longer recover them, forgetting that they lived inside of us; they had been part of us, and us, them. So we came back to our queer lives as theory – those lives that mess up the academe’s theory in their illegibility. We no longer want to seize what has built itself on our erasure; we want to queer the very meaning of production, of theory, of the academe.

And so, with this issue, we worked full circle and embraced its ruptures. We went into lockdown and s t r e t c h e d the timeline, we s l o w e d us down. Mere days after the explosion in Beirut, I moved to France, and Sabiha took over the workshop follow-ups for the month of August. Then our WhatsApps were a stream of “what happened with …” and “what about …” and “did you hear back from …” as I juggled in-between workshop interventions and submitted texts, too-often interrupted by other publication processes, coursework, French racism, a new organizational setup, French bureaucracy, a second lockdown, PTSD, and the burden of precarity. Our internal mechanisms loop into each other: I send a text to Hiba, who sends it to translation. She receives it back, she sends it to Sabah, who sends it to me, then I to Safa, who puts it out in the world. By this work of kneading, we give life to the histories that live in us.

This circle, though, is not a vicious one. It is one attempt, perhaps a failed one, at breaking away from the aimless drive of our contemporary world, forever circling but never reaching the illusionary goal of happiness that capitalism professes.

Circles became our methodology: I/we want archiving to be a praxis borne of sitting circles. I/we want to do away with introductions that begin and conclusions that end and methodologies that follow “ethical” standards that had to be made guidelines because somehow, it was okay to study people like me/us like they were objects. And so, they

the states, the patriarchs, the GPs, the supervisors

had to write in books that it was no way to treat their subjects of research, and they thought, designed, printed, distributed volumes using resources they had extracted from the South, from us.

Poetry, coding, and due citational work mirror the reassembling methodology that allows us to find coherence and cohesion in our queer narratives.

Our texts begin at the heart of our seeings, queered by our lives, real, imagined, magical. Dis/oriented, they follow the motions of our crossings and break the codes we are told are the norms. On paper, they end when seeing becomes envisioning, and our processes encapsulate joy – not in the capitalist sense, but in the sense of our collective liberations, our bodies becoming disruptions, our timelines and mises en page ruptured so they might merge with each other, again.

Soon enough, our phantasies will come to life, and with them, the inevitability of swerving away and breaking free from the current cyclic economies that tirelessly reproduce inequality, environmental damage, financial disasters, and individualistic societies of hyper-consumerism. Whereas these notions are not the most representative of this special issue, we maintain the endless possibility/ies of inhabiting imagined landscapes. We do this by taking up space, mocking conventional truths, stealing a glimpse here, a smile there, sometimes a biscuit. We reassemble our once fragmented bodies in the name of science and rational thinking. Minds, hearts, bellies, hair, and hands become one. Each and all do our thinking and feeling.

Our joy is borne of an “I” dissecting itself/ourselves for a “we.”

Our bodies is/are the archive and hereafter is its story/ies.