Examination: Four Stories Inspired by Actual Events

Cover Website.jpg

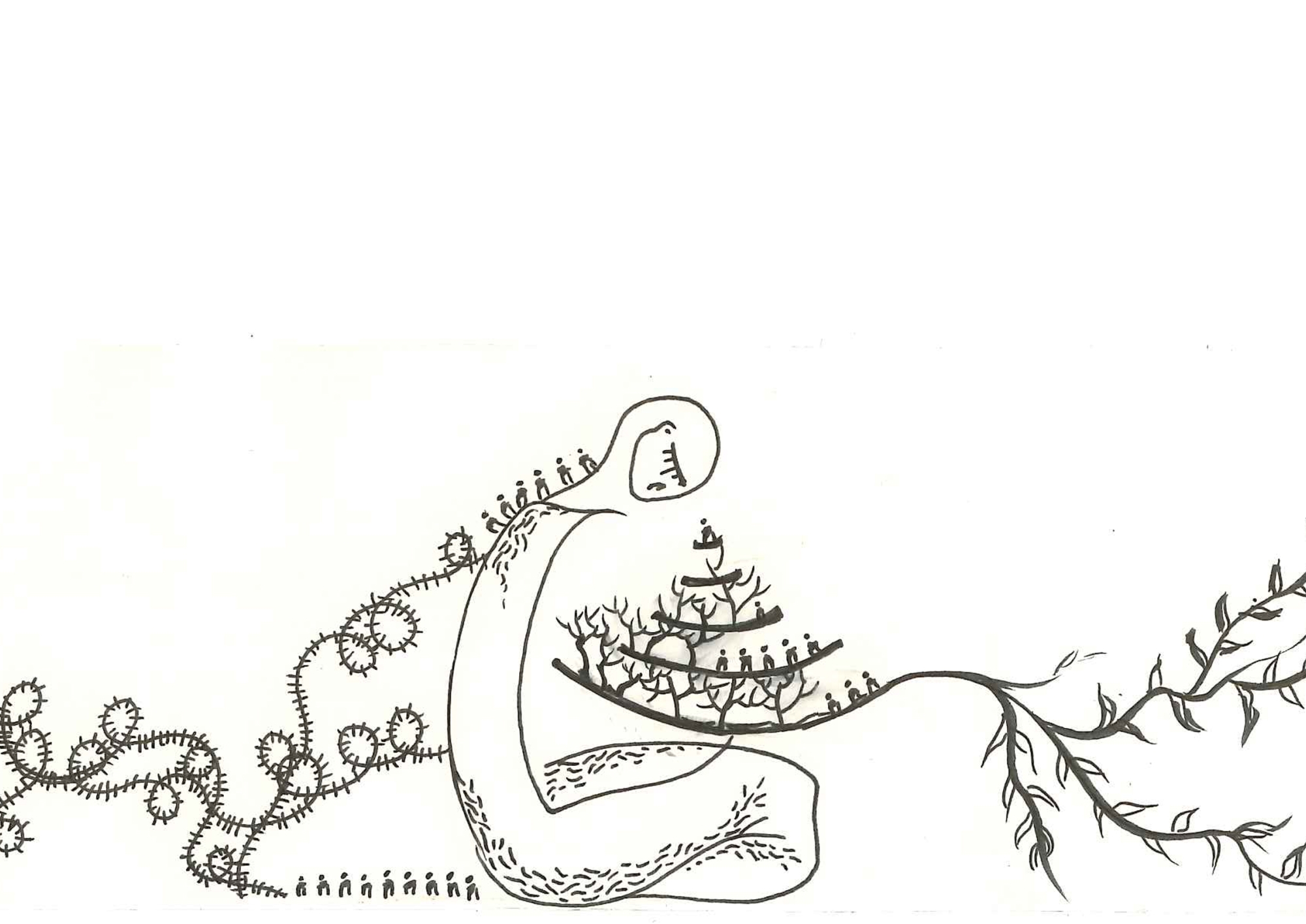

Illustration by Zeina Hamady 2018 ©

Story 1

She was wasting time on a bench, waiting for her next class, when she spotted a post on social media that encouraged her to take initiative, be responsible for her own body, and think of early detection. She felt like a child for a moment, embarrassed by the fact that she had avoided getting checked for so long.

A few days later, she was at the clinic. The person seated next to her was complaining to their companion about the burden of medical costs, and for a moment, she was fully aware of her privilege of medical insurance. Then a nurse called out her name and she followed him out of the waiting area.

The rest was a blur of white coats and anxiety. A doctor asked her if she was sexually active, then briefly explained the tests she was about to undergo. She then told her there were other tests she should consider in the future, stressing that a lot of these may not be covered by insurance, especially since she was unmarried. She was led into another room. The radiologist reminded her of a boy she knew in seventh grade; he would sneak into the girls’ bathroom at recess and try to peer into the stalls. His eyes lingered a little longer than she would have liked when she undressed for her mammogram1, and was that a smirk she saw as he turned away to tinker with the machine? Either way, she decided, as the cold glass pressed up against her painfully, that she was already there, it was happening, he was a professional, and if her mother had gotten through it before, then so could she.

She followed another nurse out of the unsettling darkness of the radiology ward and into a well-lit examination room. There, she remembers smiling awkwardly at the resident as she lay exposed on the table in her hospital gown, waiting for him to begin the procedure. It was not a comfortable position, and the test itself was much more invasive and painful than she had anticipated. It was bearable, she thought to herself. And so, when the resident glanced up at her and asked how she was doing, she said she was fine. When she caught a glimpse of the tool2 he had been using, she realized why the procedure had been so unpleasant. She couldn’t wait to get out of there.

It was about ten days later when she finally received her results. All clear. Her mother was relieved and they called her aunt to share the good news. Thinking back on that day at the clinic, she was just relieved she wouldn’t have to go back there. At least not for another year or so.

Story 2

She woke up that morning to the same sense of dread she had been feeling for the last week, ever since she had first realized there may be something wrong. Her dread, however, was mixed in with a sense of imminent relief. Relief at the fact that she would finally see her doctor today and find out what it was exactly that she had been dreading. Of course, it wasn’t just her own dread that hung over her head; her two children had spent enough time at their father’s bedside to be apprehensive of another sudden illness in the family. The anxiety was palpable as they all sat down for a small breakfast.

Later that day, she would hear the words “borderline” and “inconclusive” a few times too many. The initial scan had been made and she was lying in a hospital bed, her daughter wringing her hands in the chair next to her. Neither one of them had any more information about the four centimeters of unidentified growth on her ovary than they did that morning. When the doctor finally arrived, he did not look his usual chipper self; he wasn’t feeling good about the scan. He explained to her, prying his glasses carefully off of his aging nose, that if they were going to operate anyway, they might as well take the whole thing out. “Why take any chances? It’s not like you’re going to be having any more children,” he said, pointing to her grown-up daughter as if to say it was her job to procreate now. And so, upon seeing the look on her doctor’s face and hearing his adamant thoughts on the matter, she agreed to a total hysterectomy.3 He gave her an appointment and told her the procedure would take a couple of hours to complete and a few weeks of recovery. She would need to be very careful after her surgery so as not to get the wound infected. “By the time you’re all healed up, we would have gotten the lab results and figured out exactly what’s going on in there,” he said with a triumphant smile, “but it may not even matter at that point,” he added as an afterthought.

On the internet, she read about how the sudden cessation of menstruation would essentially mean she would be in the throes of menopause and would need to take medication for hormone replacement. She also learned that her upcoming surgery would be extremely invasive and involve a more difficult recovery than she was told. There was another type of surgery, the article said, that yielded the exact same results. It was called a laparoscopy and it seemed to be much simpler, as did the recovery. She wondered why her doctor hadn’t mentioned it at all and, deciding to be responsible, she called him to discuss the matter. He assured her it would not be successful in her case. She refused to take no for an answer and when she consulted another gynecologist, he told her that the simpler procedure was not only possible, but also much more preferable. He said he would speak to her doctor himself and sort it all out before the day of her surgery.

And so there she was, a few days later, post-surgery, happy to finally be with her children after having narrowly avoided an unnecessarily complicated procedure. At that moment, she didn’t care what the four-centimeters were made of or how they were removed, just as long as she still got to be herself, be with her family, be able-bodied and safe. The effects of her anesthetic hadn’t fully worn off yet, and she found herself asking her daughter: “Do you think it’s an empty space now? Where everything used to be.” It wasn’t until a few weeks later, when the lab results came back negative, that she realized, she had let them take away parts of her body because it was more convenient for them. The cyst was benign, the changes made to her body were irreversible, and she felt betrayed.

Story 3

It had been almost five years now since she had given birth to her second child and she still couldn’t seem to get herself back on track. She remembered feeling different after her firstborn as well, but this time was worse. For a while, she had convinced herself that the strain she felt was natural. After all, both her pregnancies had coincided with wartime. But in truth, the stress of enduring the turmoil of 1980’s Lebanon was only heightened by her husband’s disdain. Her parents had told her, begged her not to marry him, but she insisted, and they gave her their blessing reluctantly. It was about a year into their marriage when his promise of undying love began to turn into indifference. Somewhere in the back of her mind, she knew that the hardships she faced while pregnant with her children had been passed on to them somehow. Now, twelve years and two children later, she was beginning to break under the weight of her regrets and – what she would later find out to be – a severe case of postpartum depression. Her only solace was the love she felt for her children, and the hope that one day, when her youngest was old enough, she might be able to change her intolerable circumstance; divorce was undoubtedly frowned upon, but not unheard of, she kept reminding herself.

One rainy day in January, her husband walked into the living room with their two children and a look of resolve on his face. “Tell your mother you want a baby sister or brother,” he said to them. And they rejoiced.

She was torn. She did not know what bringing a third child into the world would do to her; for all she knew, this time could be different, it could be better. She had worked so hard to hide her depression from her children, even from her husband. How would she explain to them that a third child could extinguish all hope she had for a brighter future? A third child would mean she must stay, no matter how intolerable her circumstance, because that is what she believed a mother should do. She tossed and turned and wrestled with her own thoughts for nights on end, but her thoughts didn’t matter. Her family had already made the decision for her and they couldn’t wait for their new sister or brother. One day, as she passed by the children’s bedroom, she heard them arguing over what they would name the baby, and something in her chest softened; her fear of finding herself trapped once more began to slowly dissipate. She spent the next few days imagining what her third child might look like, what their first word could be, how they would turn out when they were all grown up. When she caught herself rearranging the guest bedroom one quiet Sunday afternoon, she knew she was ready, no matter what difficulties may arise.

It had been six weeks now since the doctor had told them the good news. For six weeks, all the children could talk about was “baby this” and “baby that,” and she could almost see past the shroud of depression for the first time in years. She went in for her first screening since the pregnancy had been confirmed. It was too early to determine the sex, but her youngest was sure it was a boy. She waited alone at the reception desk until someone came and signed her in. As the nurses weighed her and took her blood pressure, she wondered if she might be able to find her son’s old baby clothes somewhere. She climbed onto the examination table carefully and lay back. The doctor came into the room and engaged her in small talk while he prepared the final check-up. It was only a few minutes after he started his examination that he stopped, put his instrument down and casually tapped her on the knee. “I’m not seeing a heartbeat, looks like it’s dead,” he told her, already busying himself with someone else’s file. “You can get up now.”

Story 4

The world is unfair. That was one thing she could always count on. She always knew that her brothers' shares of the inheritance would be twice the amount of hers and her sisters', that her male coworkers would have ample opportunities to advance in their jobs while she would not, that she would always be some man's responsibility: the doctor who guided her into the world, her father, her brothers, her husband, her sons, the men who would carry her to her final resting place one day.

She had married her husband for his last name; it was the same as hers. Her brothers could pass their name on to their children but she could not, and so she and her sisters were expected to marry their cousins; that way, their children would still be a part of the family, if slightly lesser in status than their cousins. Her brothers, however, had a choice; they could marry women from a different family, a different sect, even a different nationality. She wondered what her life would have been like if she had married a foreign man. But then, that was not the life for her. She would not in a million years dare to be the only sister who defied family values. No, she would live her life the way it was intended: in solemn acceptance. She would tolerate all the unfairness, even though it seemed to just keep piling on, inequity after inequity, so much inequity that she could no longer recognize it for what it was anymore. And why would she? Her mother did not, her sisters did not. They all knew their place and she had to as well; their bodies would either be in service to the family name, or a disgrace to it.

She was approaching her eighty-second year now, and her concern for the fairness of the world, or its lack thereof, had dwindled into a deep corner of her mind, hiding among the pains of an aging body and a lifetime of worries. There was, however, that one thing she could not seem to let go. The memory was dull and incomplete, it could have been forty or forty-five years old now. She remembered going in for an examination. The doctor was her husband’s old friend. They had already had three beautiful children together, but she suspected a fourth may have been on the way. After he checked her, the doctor walked straight back into his office where her husband was waiting. They didn’t say a word to her, but she could almost hear them and she understood what they were saying. The doctor came back and began performing the procedure. She didn’t say a word to them and that was that.

It was just how things worked back then, she told herself. She didn’t really want a fourth child either, and likely would have agreed with her husband had he asked, but he had not. It was a small thing in light of such a large and eventful life, but she still couldn’t let it go. The world is unfair.

- 1. A mammogram is an X-ray imaging method most commonly used for the detection of breast cancer. It has been criticized for being highly uncomfortable and sometimes inadequate for patients with smaller breast sizes.

- 2. A speculum is a tool often used to perform Pap smear tests. Although it has undergone several improvements, the speculum remains largely unchanged since its invention thousands of years ago. The vaginal speculum is notorious for having been used as part of inhumane medical experimentation done on slave women during the nineteenth century in the United States as well as other parts of the world.

- 3. A total hysterectomy, in this case, is the removal of the uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes, and both ovaries.