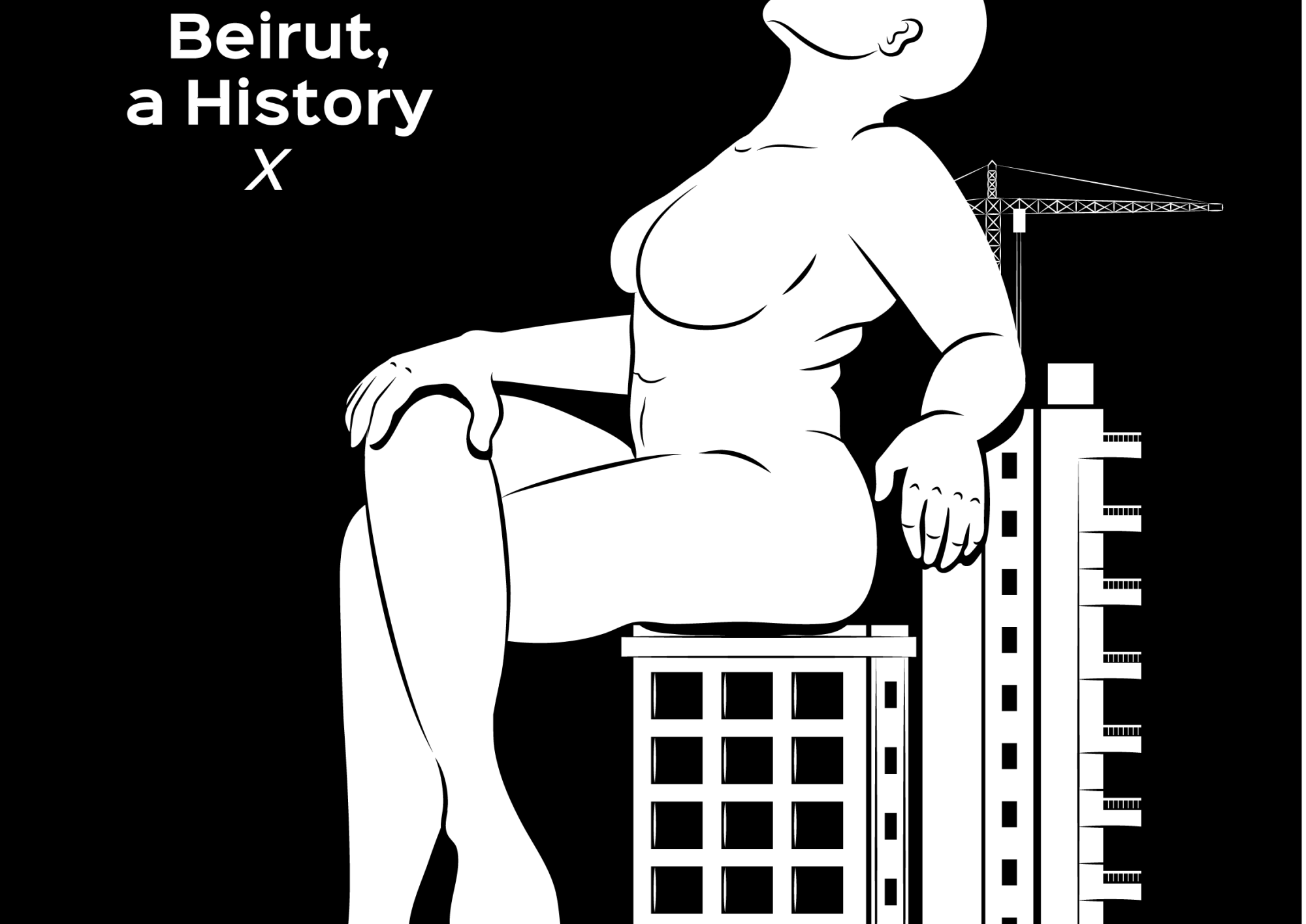

Beirut, a History

pick_2_issue_6.png

“desire is memorable only when it reaches toward something to which it can attach itself; and the scene of this aspiration must be in a relation of repetition to another scene. Repetition is what enables you to recognize, even unconsciously, your desire as a quality of yours. Desire’s formalism – its drive to be embodied and reiterated – opens it up to anxiety, fantasy, and discipline.” (Berlant 20)

“Our body takes the shape of this repetition; we get stuck in certain alignments as an effect of this work.” (Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology 58)

“The ability of the melancholic object to express multiple losses at once speaks to its flexibility as a signifier, endowing it with not only a multifaceted but also a certain palimpsest-like quality. This condensation of meaning allows us to understand the lost object as continually shifting both spatially and temporally, adopting new perspectives and meanings, new social and political consequences, along the way.” (Eng and Kazanjian 5)

Much thinking on desire is embedded within writing on sexuality, love, gender, or eroticism. In this writing, the object of desire is human, the quality of desire is sexual, and the gage of desire is sexual pleasure. But if we are to take up Berlant and Ahmed’s understanding of desire as only having a recognizable character through its repetition, reiteration and its stickiness, and if we understand desire to be a field that is socially and historically constructed, then surely we can imagine a more capacious relationality between desire, sex, and sexuality. After all, sex is a name we give to a physical act where multiple forms of transaction take place, pleasure being one. Can one not think, then, of sexual desire that is not in anticipation of sexual pleasure? Can we think these forms of desire outside of a discourse of injury at a time when the fulfillment of (particularly female) sexual pleasure is seen as a moral good – one that divides the world into liberated and repressed topographies of difference? What if the object of desire is not a person at all, but is rather something that person has, an affect or a memory that one can orient themselves towards through sexual contact? Lauren Berlant has written that “On your behalf, in an effort to release you from abandonment to autoeroticism – or, more precisely, to restore your autoeroticism to sociability – your desire misrecognizes a given object as that which will restore you to something that you sense effectively as a hole in you” (76).

There are many holes in any given person’s life. These holes, or gaps that one experiences as in need of filling or addressing, are not only sexual or romantic or love-oriented. Indeed, the primary desire (or hole that is experienced as in need of being filled, as it were) may be oriented towards something not contained by a human body at all: it could be a desire for history, for grounding in place and time, for intensity. It could be a desire for power or knowledge. In fact, sex may not be physically pleasurable at all, but that may not mean that it is devoid of desire. Moreover, sexually pleasureless does not have to be an expression of “thwarted” desire (desire doubled back onto itself), a practice of false consciousness (what is often rendered “being closeted” or internalized homophobia), or an in-retrospect insincere desire. These statements represent a distilling of both desire and pleasure to their sexual registers, one that is perhaps necessary to produce the “truth” of sexuality (Foucault 1984). But there are desires that do not accumulate and produce a reiterative orientation towards gendered bodies – an orientation that we call “sexuality” – even if they are often routed through sex. While they may not produce sexuality, these practices of desire can still produce orientations – towards objects, discourses, histories, emotions, and towards others and oneself.

I was twenty when I started noticing that my patterns around sex and love primarily orbited women. In repetition, my desires began to congeal – and desire seemed to stick better and more securely to other girls, to paraphrase Sara Ahmed (“Orientations” 563). I had already fallen in love with a woman and had learned how to have sex with a female body. It was only when it happened again (and again) that I felt something begin to settle, and it was terrifying. It felt as if I risked a temporal rupture, that the days from then on would be a radical departure from those that preceded it. I could no longer recognize the future or myself in it. When I began sharing this information with those around me – that my desire for intimacy and sex had become harder, narrower, and stickier, it coincided with me starting to use the word “gay” as a placeholder for this compulsive repetition; their unsolicited advice was almost uniformly simple: “Leave.”

I told my sister one night as we were watching television in our pajamas. After assuring me that my sexuality was not a problem for her (really), she said, very confidently: “you shouldn’t stay here.” In that moment I hated her. Only six years ago my mother repeated this advice, reversed, when I finally told her what I was: “Stay in America. It’s better over there. What kind of life can you have here?” At the age of twenty, placing myself under the sign “gay” performed an unbearable difference. The older and queerer I get, the more I realize that so much of this advice, though well-intentioned, had as much to do with those who were giving it as it did with me. My absence was less of a rupture to the family than my physical presence as a daughter or sister who deviated from a heterosexual path (Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology 20).

It made sense. I had a U.S. passport – I had freedom of movement. The imagined life of a “gay” female in Beirut in the year 2000 was not exactly positive. Before I had used the word “gay,” friends and family members had known of my consumptive and multiple habits and desires. I was perhaps naively surprised: in my mind, I was naming a pattern of emotional and sexual attachments that highlighted experiences with female-bodied persons, but that was neither predictable nor settled. It was nothing that my sister did not already know, for example. It seemed to me, then, that they gave too much power to naming.

It was easier than you would think, living with unsettled desires in Beirut. The late 1990s felt like living on borrowed time, and I had the money and the freedom of movement that such borrowing required in a post-war third world city. I was a pretty girl whom men liked and who liked that those men liked her – I enjoyed playing with desire. I used it as a balm. As long as I continued to be recognized by men, I felt much more confident in my interactions with women. Part of me must have hoped that their recognition would stick – that their desire for me would keep me tethered to a world so familiar and comfortable and fluent. A life so ordinary. Today, I teach my students that this world is called “heterosexual privilege,” or “compulsory heterosexuality.”

I still sometimes display myself in that way – holding someone’s eyes to mine in a crowded room – touching arms and hands during conversation – moving my body in ways that demand attention. I still enjoy playing with desire, its surprises and its reversals. Sometimes, the exercise is so simple that it makes me laugh: wear a dress, put some makeup on, and see what happens. I get off on male desire – my sexual experiences with men have always seemed narcissistic and masturbatory. I don’t enjoy their bodies. But I enjoy their want of my body. This is desire for male desire, not desire for men. I take from these encounters alternative versions of myself, the power of the possibility of sex, their image of a woman who is attractive. I take from them, perhaps, a performance of gender. These desires are neither reiterative, nor do they have a social life (they are not easily lived as heterosexual privilege). They do not stick or condense into sexuality (as an inclination towards embodied gender). Delinked from the anticipation of pleasure or the truths that sexual pleasure is supposed to reveal, the possibilities of transaction and play within a field of desire proliferate. Here, desire is not sovereign, and neither is the desiring body. Instead, in this framework, desire is a dense social field, not an affect, sensation, or need that emerges from one person and attaches itself to another(s). In this social field of desire (I am not naming “hetero” or “homo” desires), heterosexual and male desire are privileged sites. Queer “orientations” are just that – orientations towards others within this masculinist social field of desire (Ahmed 2006; Butler 1990; Lorde 1978). Announcements of desire rely on that larger field for intelligibility. Desire – reliant as it is on others and constituted through other forms of relation (such as class, race or, in Lebanon, sect) – is never alone, although it may often feel lonely.

Bringing together poststructuralist and psychoanalytic theorizations of desire, Judith Butler has suggested that heterosexual melancholy emerges from the foreclosing of homosexual desires – a foreclosing that produces and haunts heterosexuality (89). In similar ways, she has suggested that homosexual melancholia marks excess that cannot be contained within homosexuality. But if “The ability of the melancholic object to express multiple losses at once speaks to its flexibility as a signifier,” (Eng and Kazanjian 5), then the loss entailed within sexuality is not, and perhaps is not primarily, sexual. Desire, as a field that is constituted through and constitutes gendered, classed, racialized, and sexualized bodies, objects, and affects as always in relation to each other, has a locatedness – a stickiness in time and place – that cannot be uprooted. What if we were to emphasize the historical, political, and economic histories and contexts that produce any given field of desire? If the losses and pleasures entailed in turning away from the “hail of heterosexuality” (Ahmed 2004; Freeman 2010) are refracted across historical, racial, gendered and classed difference, and if heterosexuality itself is not the same thing everywhere all the time, then why assume that the condition of possibility for queer subjectivity is the reiterative turning away? In Lebanon, for example, turning towards male desire, or hailing oneself into it, can often provide needed currency in a heterosexist and masculinist socio-political space. What kind of body is being produced when one hails themselves into heterosexual orientations of desire, not for pleasure or truth or as an exercise in false consciousness, but rather, to make queer life livable? To pause on such historical and ethnographic difference is to call into attention the unmarked nature of much of queer theory.

One night in 2005, I received a phone call telling me my “fiancé” had been arrested for public lewdness in a posh area of Beirut. I have never been engaged or married to anyone, but I knew, almost instinctively, that my fiancé that night was my best friend and that the public lewdness in question was related to male-male sex. I knew that I had to show myself at the jail – and I knew how to show myself. In a short skirt, cleavage, heels, and an upper class haughty affect, I made myself available for an internal security officer’s interrogations about my fiancé and our relationship. I made myself available for his desire. I actively and consciously turned when hailed by it – perhaps I even called myself into it. I performed for him, and I felt strong and confident doing it. It meant my friend was someone (a man) who could have the woman that the officer wanted but could not have because he was from a different social and economic world. My body, my gender, my socio-economic class, and my welcoming of male desire while maintaining a “proper” (not too available or “easy”) orientation towards it – these were performances directed at the thickness, riskiness, and multiplicity of desire. I was positioning myself, and my fiancé, within a field of desire where orientations around sect, race, class, and social status were intractable from orientations around gender and sex.

This positionality, or this turn towards heterosexual desire, allowed for alternative narratives for sex between men, and introduced doubt into what the police officers “saw” in that parked car that they named sex (Povinelli, 2006). That perhaps this was not a homosexual sex act, but rather an intense practice of the homoerotic. A new description was offered: these men were not homosexual because they were pleasuring each other; they were just horny guys who had worked themselves up talking about women and how large their penises were. In fact, that night, it seemed that the officers and myself were insisting on the non-fixity of desire – that sexual acts do not necessarily express a deep-seated truth about a person’s identity. While the act that police officers saw had not changed (two men with their hands around each other’s penises), there was now doubt as to what they had seen. The new description of the “homoerotic” rather than the “homosexual” may not seem convincing, but it didn’t have to be. It allowed for enough movement – enough possibility – for the privileges of class to take over. As one of the officers told me, perhaps in order to convince me of my own engagement to someone caught with his pants around his thighs, “a man like that, I knew there must have been some kind of mistake.”

My fiancé of that night and I have known each other intimately since we were teenagers. We are both comfortable using the word “gay” as shorthand for the directions of our sexual desires, and we largely came into this sticky category together, alongside a social scene that emphasized physical, emotional, and psychological intensity – a scene that emerged in post civil war Beirut. To circulate this statement into larger context: Lebanon was locked in a civil war that was punctuated by military invasions and occupations from 1975 to 1990. By the time that those around me were saying the word “post-war,” I was twelve years old. Too young to remember much detail, but also too young to remember a “before.” When the war ended, so did public conversation about it. We simply woke up one day and were told an accord had been signed and that there was “peace.”

In the 1990s, bars were everywhere, nobody checked IDs, and everything was possible. An evening, especially for those of us who had pocket money and felt comfortable inhabiting elite spaces of consumption, might begin at Pacifico or Monkey Rose or Smugglers Inn or BO18, and end with a bonfire, greeting the morning somewhere on the shores of Jbeil – an area I had that was off-limits a couple of years earlier because it was on “the other side” during the civil war. There was also Acid and Orange Mechanic and Babylon and the rest of it. For my friends and myself though, it was mostly Acid – a club that was often touted as Lebanon’s first gay bar and the first openly gay club in the Arab Middle East. At Acid, everything and everyone was on display and the possibilities seemed endless. This was before management removed the bathroom stall doors and before they posted a security guard there to police the illicit couplings, both sexual and narcotic, that had made those piss-reeking rooms ours. There we were, dancing and beautiful and young and sparkling with glitter and the male and female bodies that pressed against each other in no particular patterns. And that was the point: there we were. Of course, now I know that we were particular: our parents gave us money and freedom. They didn’t ask where we were and it was fine to sleep outside the house. We were all cis-gendered. We could give the police an alternative narrative as we coupled up heterosexually when they engaged in a raid in order to gather the club owner’s bribes that were perhaps late that month. In these spaces, we played with desire.

There were also house parties. There, drugs – all rolled and lined and pretty and sitting on silver trays – were offered in much the same way as our parents used to lay out trays of cigarettes for guests. For a time, a hit of heroin cost less than a beer at a bar and everybody believed that needles were what were really bad – an unspoken red line that separated us from “them.” At these parties there was so much music, reverence, and anticipation. Sensation was all that mattered. This was typical college-aged behavior, but with the force of teenagers who had spent too much of their lives with family in hallways or underground parking lots hiding from bombs or snipers or raids, not fully understanding the terror in our parents’ faces but feeling it. Knowing it.

It is hard to explain to anyone who wasn’t there. Nights that took us all over the country in search of a particular drug or high, weekend parties where sexual groups formed and re-formed without discernable patterns. There was so much dancing, so much arguing, so much sharing of personal histories and turmoil, and so much love. Any one person could find himself or herself inclined towards another, and none of us were shy about those inclinations. We did not assume that our nighttime activities would reveal something to us the next morning. We were not interested in bolts of lightening or self-awareness. We were acting with an intensity that couldn’t be explained by any description of hedonism, drug abuse, trauma, or sexual experimentation. In fact, I don’t remember ever having a tortured conversation about sexuality – whether mine or others’ – during those years. Most of our conversations – those that have stayed with me, were about our experiences of war, destruction, and the furious pace of reconstruction – a process that was erasing so many of the signposts of our lives. There was no public discussion of the war. It seemed as if everyone was desperate to forget the over 150,000 dead and 300,000 maimed, the mass graves and massacres, and the checkpoints and the physical demarcation of a country into militarized spaces invested in the destruction of the other.

At these parties, in these couplings, we learned about the country and sutured together a history: I learned what my lover’s childhood in Kaslik was like, and, for the first time, I experienced sympathy for anyone living on “the other side” of a war. She told me of a week where all her family had to eat was chocolate, and I shared a scene I witnessed of my father fighting with his cousin over three loaves of bread that were supposed to feed two families. She told me of a night when the Lebanese Forces raided their apartment and stayed up all night drinking their alcohol and looking to collect a “tax” from her mother – I told her of how I used to fantasize about shooting a machine gun at the entrance of my apartment in order to fall asleep. My best friend and I, the same relationship that would be produced for a night as an “engagement” years later, would get high, play music, take our clothes off, and trade stories about the war time engineering skills we had learned, he in Dahieh and myself in west Beirut. As naïve as this seems now, at the time I was shocked that they were the same skills. We spoke about all the games we would play in makeshift bomb shelters, about the bodies we had seen and smelled, and I shared with him how, years after the war had ended, I couldn’t get used to routine. Sometimes, we would make out, and I wanted the feel of his skin and the smell of his breath – it provided me with comfort, with stillness, with the understanding that we were alive and that the past had actually happened. We were both beginning to use the word gay, but that never stopped us. There was desire: we wanted, and needed something from each other.

My core group of friends has remained unchanged – sometimes, we spend days reminding each other that all of these histories did happen, that when we were teenagers we were convinced that life could not contain us, that our desires, our propulsions and compulsions and inclinations were much too large and urgent for the world that was given to us.

Today, almost two decades later, most of this group has arrived into categories. We are more or less well-adjusted professional adults. We are gay, we are straight, we are married with children, we are single, we are monogamous, some of us are still looking, others have decided that desire should never stick to one singular person. But when we get together, we trace our travels from there to here. We speak of the past as liberating and as creative, as filled with contradictory steps and open-ended questions. We laugh at ourselves for how predictable we seem today, how ordinary. How small.

“Homophobia” makes sense in today’s Beirut (especially in particular areas of Beirut) – it is part of a lexicon hard-won through activism and through tragedy. This naming aggregates aggressions that might also be understood as gendered or racial or economic. For example, the sign “homophobia” is the marker most use to describe incidents where working class or racialized migrant laborers engaging in male-male sexual behaviors are attacked or brutalized. Perhaps this is not surprising given the every-dayness of violence (sexual, physical, psychological) directed against migrant labor (including “domestic labor”) or refugee populations. With the description of “homophobia,” the ordinariness of these assemblages of violence are marked and routed through gay rights groups, organizations, and discourses that are positioned differently than those that work on sexual and racial violence among racialized and classed vulnerable populations.

As a description of intentionality propelling action, homophobia requires and produces a homosexual body as the primary marker, or site, of aggression. It requires a world of fixed desires, and an understanding of desire itself as anchored in the gendered body. A discourse on homophobia, connected as it is to gay rights struggles, also requires a past, an archive of injury and of thwarted desires that can now be named and redressed (Rupp 1999). Heather Love has explored this affect as “feeling backwards” (2007). Love writes that the search for queer lives and histories emerges from a desire for historicity that cannot be disarticulated from violence and tragedy, particularly because expectations of violence and tragedy continue to structure queer life (32). These expectations, however, structure many forms of embodied life across national, racial, and classed lines. One could easily imagine replacing, for example, “Palestinian life” for “queer life” in Love’s sentence. To live otherwise, with the expectation of safety or happiness, is an unattainable ideal for much of the world. (Berlant 2012; Halberstam 2005)

To live in Lebanon – a country pockmarked by civil wars and military invasions – is to also live in anticipation of violence and tragedy. The precarity of queer life is not exceptional in this socio-political space: it is additional (Mikdashi and Puar 2016). Sectarianism is the discourse most often used to describe this history of violence. The hegemonic nature of a discourse of sectarianism flattens much of the complex and contradictory nature of violence in Lebanon – and it assumes that sectarianism itself is transhistorical (Makdissi 2000). In ways similar to homophobia, sectarianism is understood to be a violence that is directed against embodied identity – one is killed or injured because of who they are. Like the naming of “homophobia” to describe a violence that is multifaceted, the corpse that is a sect is produced through the recognition of its killing as “sectarian.” Both anti-sectarian and gay rights activists use sectarianism and homophobia to describe past violences and injuries – an anchoring in the past propels us into the possibility of a new future. Because civil war violence has been marked as sectarian, anti-sectarian activists desire secularism as that which will deliver peace. Because racial, gendered, and classed violences have been marked discretely as “homophobic,” gay rights activists desire a future time that is different than the past, one where they can be who they always were.

The interpellation of history into sectarianism or homophobia forecloses alternative descriptions of violence and the political futures those descriptions may have had. In doing so, they can produce a melancholic orientation towards the archive, towards what Foucault has called “insurrectionary knowledge” – histories that cannot be contained by sectarianism or homophobia. A melancholic orientation towards an archive is, perhaps, one that grapples with “continuous engagement with loss and its remains. This engagement generates sites for memory and history, for the rewriting of the past as well as the reimagining of the future” (Eng and Kazanjian 4). While a melancholic orientation towards an archive may produce different significations or new descriptions with which to describe past actions, these descriptions remain insurrectionary and do not rise to the level of “discourse.” Perhaps in the act of orientation, the archive, routed as it is through the researcher, is itself melancholic.

The use of sectarianism or homophobia as descriptors of the past may help us, as those that are invested in political change, make sense of our world. They provide a logic or pattern to indeterminate but spectacular violence that is both world-making and world-breaking. They promise that our sectarian, heterosexual, and homosexual bodies have historical, local, and spatial precedent – that in working against today’s sectarianism or homophobia, we are addressing a historical wrong, we are honoring the dead, and perhaps redeeming them. But “sectarianism” or “homophobia” are not passive descriptions. They actively intervene in the world, and they both announce and perform the presence of a marked (through sect and sexuality) and violated body.

Years ago, I sat with my girlfriend at the time on the Corniche. We were facing each other, talking over cups of coffee. A man walked by and shouted the word “lesbian” loudly, in English. My (much) younger girlfriend shouted back at him, but I felt completely untethered. I had been called names before (“dyke” seems to be the preferred term), but only in the United States, and never in Lebanon. At that moment, I wanted to hide – I felt as if some secret pact between myself and the city, between my past and my present, had been broken. On Beirut’s streets, I have been called fat, stupid, and a slut – but never anything related to sex that wasn’t an instance of (heterosexual) sexual harassment. And yet there I was, in my late twenties, being publicly insulted as a “lesbian” for the first time in Beirut as I sat facing my girlfriend drinking a cup of coffee.

I have engaged in many practices that could be understood as “sex in public” in Lebanon. I have “taken care” of a boyfriend who whispered his desires to me through the metal grate of a confession box. He was wearing priests’ vestments that had been left at the altar, and I walked from my side of the confession box to his. It was almost midnight and we were at the church in Harissa. It was the first time I had been to a Maronite church, and the first time I had been to that area, which is a stronghold of civil war factions that I grew up hating and being terrified of. That night, my fear and excitement of being caught had as much to do with the trespasses of sect, history, and war than it did with religion or sex or the space as a “church.” I felt strong and defiant in that confession box, but it wasn’t a sexual catharsis I was experiencing.

I have coupled with men in the backstages of Masrah al Madina, Picadilly, and my university theater. In abandoned buildings slated for demolition, in brand new soulless shopping malls that were built at the turn of the decade, on the roofs of buildings pockmarked with bullet holes and filled with strangers – these were spaces where I learned about my body. I had sex with a girlfriend in the parking lot of a well known fast food restaurant near the site of an infamous massacre that had pitted “her side” against “mine,” on the hard ground of an open campground under stars that were moving so fast I felt I was flying, in too many backseats of speeding cars on highways cutting across the country to remember, and of course, in the sea on those hot Lebanon summer days. One night, a man told me of how his father died while convalescing in a hospital, collateral damage when an explosive went off on his hospital floor in a failed assassination attempt aimed at a militiaman also convalescing at the hospital. We were walking on the corniche past midnight, drunk and high and happy to be together. I led him to a railing, pressed against him, and guided his hand under my skirt and inside me.

As improbable as it may seem, I never got caught.

It is tempting to view these past experiences as either revealing truths about sexuality or tracing the stumbling of sexuality as it unfolds into a direction – as sexuality “acting out” in a desire to become fixed. This particular sexual history happened before I was twenty-one, after I had started using the word “gay” and before I moved to the United States in order to be, as I was told by those around me, a lesbian. I have now primarily lived in New York City for twelve years and have never engaged in behavior that might be described as “sex in public.” I never felt the desire to own, or to claim, NYC as my home. I have not felt the desire to be rooted in place and time, a desire for historical intimacy, or an assurance of the past that I did all those years in Beirut. I have never desired history itself (Freeman 2010).

But then again, recently, a woman – one who desires me, desires my desire for her, and who moves through the field of desire as one oriented towards male bodies – held my hand on Hamra Street. After a few steps, I realized it was the first time I did not flinch and let go, there, in my city. I remembered how at eighteen, I was very careful not to touch my boyfriend on these same streets, but how I wouldn’t think twice about hugging a female lover because there was a proliferation of descriptions to play with. But now it is different. I felt the fear of homophobia and sexism as we walked hand in hand down a road that led from a bar (where she did not touch me) to her apartment (where the plan was to have sex), drunk and laughing. I told her that this was my first time.

She smiled and said that as a foreigner, this city was just that to her: a city. That she wasn’t yet attuned to what she could and could not do in these streets and that the investment in that knowledge did not carry the same weight as it would for me. This homophobic city, she said. She squeezed my fingers and I felt that familiar comforting rush of desire – an assurance of self.

But alongside the blush of excitement on my face and the heat in body at the holding of her hand in public – the intensity of what is now risky behavior, I felt a deep ambivalence – a melancholy.

Ahmed, Sara. “Orientations: Toward a Queer Phenomenology.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 12, no. 4, 2006, pp. 543-574. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/202832.

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke University Press, 2004.

Berlant, Lauren. Desire/Love. punctum books, 2012.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 1990.

Eng, David L., and David Kazanjian. Loss: The Politics of Mourning. University of California Press, 2003.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. 1984. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2012.

Freeman, Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Duke University Press, 2010.

Halberstam, Jack. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. NYU Press, 2005.

Lorde, Audre. “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” 1978. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. 1984. Crossing Press, 2007, pp. 53-59.

Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Harvard University Press, 2007.

Makdissi, Ussama. The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon. University of California Press, 2000.

Mikdashi, Maya, and Jasbir K. Puar. “Queer Theory and Permanent War.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 22 no. 2, 2016, pp. 215-222. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/613189.

Povinelli, Elizabeth A. The Empire of Love: Toward a Theory of Intimacy, Genealogy, and Cranality. Duke University Press, 2006.

Rupp, Leila J. A Desired Past: A Short History of Same-Sex Love in America. University of Chicago Press, 1999.