From the Red Army to Queer Feminism: Japan’s Solidarity Movement with Palestine

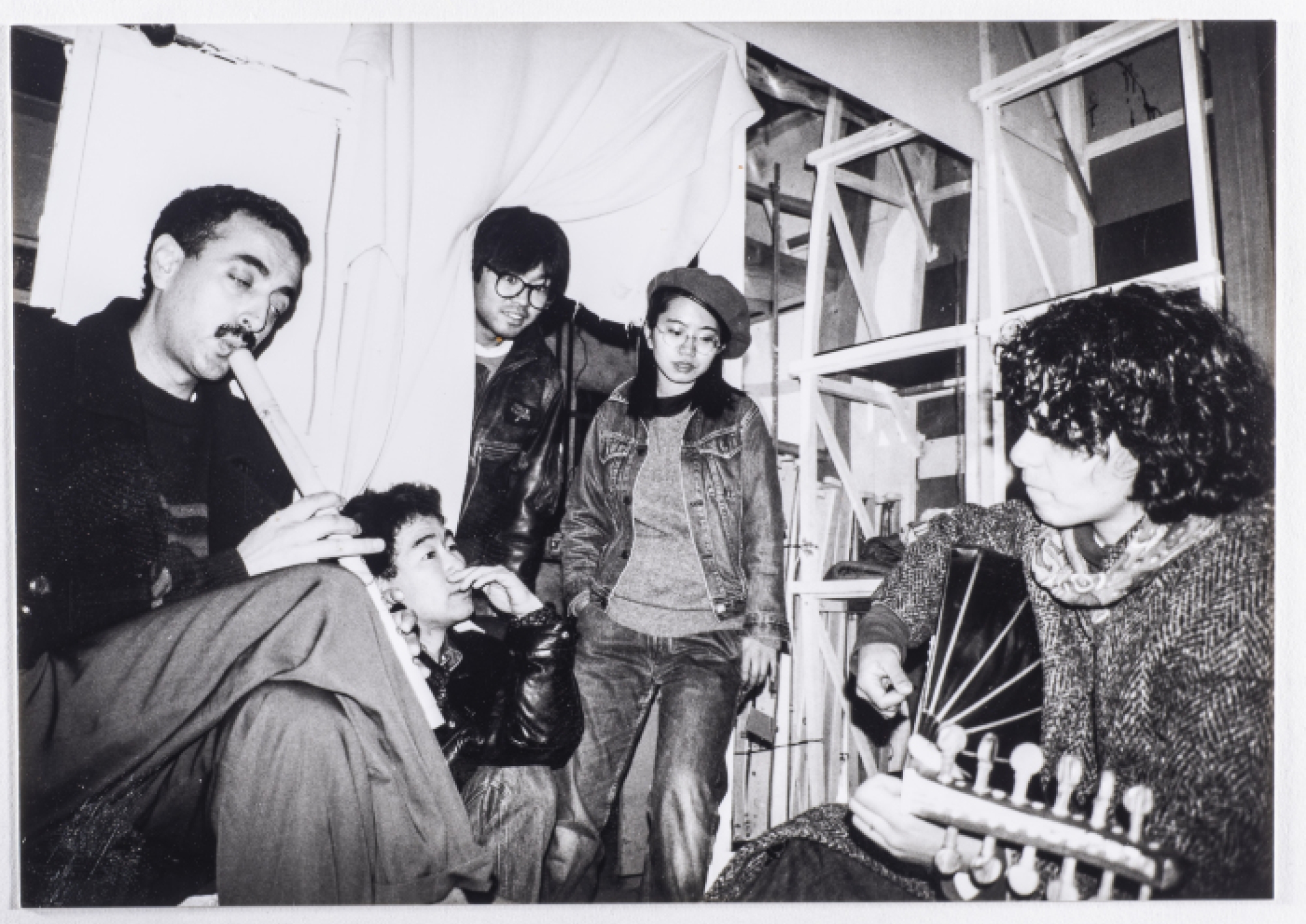

1_sabreen_japan_tour._1992.jpg

Sabreen’s Japan Tour, 1992. The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive.

The Japanese solidarity movement with Palestine has two intertwined aspects: historical lineages and newer dynamics of political involvement. This solidarity, despite spanning decades, remains little known to the larger public. This article centres the work of local activists, artists, and scholars alike to construct a digital archive that documents this political history.

In addition to providing an overview of the history of anti-zionist political activism in Japan, the piece is structured by threads that go as far back as the 1950s. In recent years, queer feminist engagement has revived the Palestine solidarity movement; recognizing struggles as indivisible, it has pushed back against Japan’s LGBTQ+ scene’s involvement in Israel’s pinkwashing and its complicity in settler colonial violence. But an intersectional lens has also urged reflections within the anti-zionist movement itself, with activists turning inwards to confront their own legacy of imperialism and colonial history.

This archive stems from my attempt to articulate why and how, as a Japanese student in Middle East politics, I engage in the Palestinian struggle – a question I asked myself and was asked when I joined the protests for Palestine. Researching Japan’s intersectional solidarity movement revealed how the country is deeply embedded in the global structures sustaining violence in Palestine, and looking for the movement’s historical traces reminded me of how activists in Japan have long resisted these dynamics. Documenting these vibrant forms of organising is a way to reflect on these entanglements and to recognise that Palestine is not a distant issue, but one that is connected to Japan and beyond.

Post-WWII: The Limits of Armed Militancy Inside and Outside of Japan

After the Second World War, the collapse of Japan’s imperial regime paved the way for oppositional political actors. Protected by constitutional reforms guaranteeing freedom of speech,1 the Japanese Communist Party (JCP),2 which had been criminalised during the imperial era due to its communist ideologies, quickly became influential.3 Inspired by China’s 1949 Communist Revolution, the JCP soon instigated a guerrilla warfare aimed at socially transforming Japan.4 However, the violent clashes between the JCP and the U.S. occupation policy against communism exhausted the JCP and deprived it of its popular support.5 Faced with these pressures, the JCP opted for a radical shift: in 1955, it denounced the use of violence and prioritised coalition-building through peaceful means.6

JCP’s policy of disarmament sat uneasily with its dissident members, many of whom were students who sought revolutionary transformation.7 Student leaders subsequently formed independent groups that became collectively known as the New Left. Inspired by overseas revolutionary writings, including those of Leon Trotsky, Che Guevara, Frantz Fanon, and Mao Zedong, this New Left viewed Japan as part of global, capitalist and imperialist architectures.8 In turn, the New Left sought the cultivation of an internationalist consciousness informed by transnational anti-imperial alliances.9 It was against this backdrop that the Japanese Red Army Faction (RAF) came to be.

With this internationalist turn, the RAF pursued anti-colonial allies abroad. They were particularly interested in receiving military training, an opportunity largely unavailable inside Japan (ibid.). For all their aspirations, however, the RAF’s vision for a Palestine-centred internationalist movement never took off fully. This was largely due to the prioritization of domestic affairs by the RAF leadership in Japan. Soon, a small faction, under the charismatic leadership of Fusako Shigenobu, broke away from the RAF and became known as the Japanese Red Army (JRA).10 In February 1971, its first members flew to Lebanon to join the PFLP for the purpose of military training and kick-starting the process of establishing an international base.11 In May of 1971, the JRA invited leftist film directors Koji Wakamatsu and Masao Adachi to record JRA’s members lives among Palestinian fedayeen in Palestinian camps in the documentary Sekigun-P.F.L.P.: Sekai Senso Sengen [Red Army-PFLP: Declaration of World War]. Sekai Senso Sengen was not screened in public theatres and remained confined to closed screenings initiated by the directors in select leftist circles.12 Despite its limited publicization, however, it remains Japan’s first public expression of solidarity with Palestine and offers a striking glimpse into the radical leftist solidarity of the time.

Sekai Senso Sengen relies on a contrasting exercise whereby footage of everyday living in the camp is interrupted with Japanese TV commercials. The cognitive dissonance produced by this exercise serves primarily for a critique of excessive consumerism.13 Still, and despite its anti-colonial aspirations, Sekai Senso Sengen ultimately conveys a romanticist portrayal of Palestinian armed resistance that recalls Sa’ed Atshan’s analysis of French queer artists’ solidarity with Palestine in the 1970s.14 Following Atshan, this solidarity was largely motivated by a sexual fantasy about fedayeen fighters and a subversive drive to rebel against hegemonic norms. Similarly, Japan’s New Left, who found itself engrossed in its “mass consumer society”15 and made little progress in mobilising the public against it, turned to the PFLP camps as a site where they could fully commit to anti-capitalist ideology.

For leader Shigenobu, this solidarity was a site of another struggle. Like other women committed to the New Left ideology, she was disillusioned by the misogyny endemic in leftist circles.16 While radically opposed to the JCP’s existing hierarchy, which treated students as subordinate to workers, the New Left proved to be complacent, even complicit when it came to patriarchal power structures.17 Female members were expected to uphold gendered norms. Sexual crimes such as gang rapes were not reported, despite them being common knowledge.18 Sekai Senso Sengen reflects a failed attempt19 at exploring women’s role in the revolutionary struggles. The documentary prioritises male-exclusive spaces and homosocial bonds to the degree of idealisation. Women’s participation, on the other hand, is mostly relegated to the background. If and when centred, they either emerge as naive aspiring soldiers who act clumsily around firearms, or as exceptional figures such as Fusako Shigenobu and Leila Khaled.

In 1972, one year after the release of Sekai Senso Sengen, two events proved decisive to the fate of armed leftist militancy. Outside of Japan, the JRA conducted the infamous Lod Airport operation.20 Internally, the United Red Army’s standoff with the police, aka Asama Sanso standoff,21 was broadcast live nationwide. Both events were extensively criticized and rejected by Japanese society, effectively ending the armed resistance and communist aspirations of Japan’s radical left.

The role and place of the use of violence, far from constituting a linear narrative, was highly contested in the broader Leftist space.22 Particularly, incidents involving civilian casualties raised moral dilemmas among the activists over the boundaries of insurgent violence.23 However, the Japanese media flattened these complexities, adopting a binary narrative instead: violence was almost exclusively associated with radical groups, while police crackdowns were portrayed as neutral measures to maintain order, despite their ongoing assaults on Leftist activists.24 As Steinhoff notes, these “incomplete” depictions strongly shaped public perception of the New Left as violent and lunatic radicals.25 This reductive framing not only suppressed critical discussions around the use of violence in struggle, but also extended to and stigmatised broader political activism in general.

1972 thus marked a turning point in which the violent trajectory of New Left activism – both in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle and within domestic movements – lost momentum.26 The Japanese general public increasingly viewed political activism with suspicion, while activists themselves were disillusioned by disciplinary hierarchies and violent orientations within the radical groups. As a result, activists opted for alternative forms of advocating their views, which Steinhoff describes as an “invisible civil society.”27 Activists connected with people and shared ideas and concerns through loose, informal networks.28 This form of participation did not demand a strong, exclusive commitment. Occasional events such as film screenings, exhibitions, or demonstrations were organised by temporary committees that could be dissolved without leaving any formal trace.29

First Thread: Sabreen Japan Tour

In 1992, the renowned Palestinian musical band Sabreen30 was invited to Japan.31 The organisation of the tour highlighted key elements of the Japan-Palestine solidarity movement at that time: loose networks, intellectual leadership, and cultural engagement. Originating from Jerusalem, Sabreen was known for its bold approach combining traditional Arabic instruments and poetry with international music styles, such as jazz and rock.32 The band aspired to raise awareness of Palestinians’ lived experience under Israeli occupation through music. True to its name, Sabreen – “the Patient Ones” in Arabic – the band’s music served as a cultural form of resistance.

Their Japan tour was organised by a temporary committee led by Tsuyoshi Okada, a Palestine solidarity activist well-versed in Arabic music.33 Okada’s first contact with Palestinians as well as with Japanese activists expressing solidarity with Palestine was in 1982-1983, when he lived in Syria as part of Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers.34 He later recalled a dissonance between his understanding of the Palestinian freedom movement – shaped by his first-hand encounters – and the romanticised images held by Japanese activists. As Aoe Tanami, an Arabic literature scholar and activist, noted in a conversation with Okada, the geographical and cultural distance between Japan and Palestine limited the general public’s ability to get involved with the solidarity movement.35 Consequently, core members were typically individuals with the financial resources, international mobility, and language skills. Academic intellectuals and journalists thus formed the backbone of the solidarity movement.

Cultural engagement became one of the key components of anti-zionist activism, especially in the post-1970s society when explicit political protest declined in popularity. Music, literature, and film became essential tools for disseminating knowledge and speaking about Palestine.36 Sabreen’s Japan tour was a markedly successful case. Flyers depicting the songs’ lyrics in Japanese were supplemented by footnotes detailing the historical context of each.37 In addition, the concerts were paired with screenings of Canticle of the Stones,38 a film that depicts the Palestinian struggle through the story of a Palestinian couple during the First Intifada.39 This powerful collaboration created a space to learn about the Israeli occupation from a Palestinian standpoint.

Second Thread: Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement

While various Japanese engagements for the Palestinian cause had been organised to respond to the historical developments in Palestine,40 greater coherence within the movement emerged with the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement. In 2005, the Palestinian-led initiative called for “boycotts, divestment, and sanctions against Israel until it complies with international law and universal principles of human rights.”41 This transnational movement provided Japanese activists with clear, actionable strategies to stand with Palestine.42

In Japan, boycott campaigns by civil society organisations grew over the 2010s and culminated in the formation of BDS Japan in December 2018. Led by Palestine Forum Japan,43 an NGO founded in 1999 by intellectuals and activists, the Japanese BDS campaigns pressured stores and events to remove Israeli products linked to the occupation of Palestine. Tactics informed by the BDS movement proved to be effective, and in some cases, store owners and venue managers met the BDS demands to avoid social disruptions.

2_boycott_marathon._2018.jpg

“Peace and justice in Palestine. Free Gaza! Israel Boycott Marathon Demonstration.”

Kazuko Matuo, Photograph from the Israel Boycott Marathon Demonstration, 2018. https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=1330812600395761

Significantly, the BDS movement raised public awareness of Japan’s entanglement in the Israeli occupation of Palestine. In 2002, Yoshihiro Yakushige, an activist intellectual who liaised with members of the Palestine Forum Japan, questioned the lack of knowledge about Japan’s political and historical involvement in West Asian geopolitics, even among anti-zionist activists.44 However, the BDS call addressed this concern by urging people to pay attention to the complicity of local organisations in sustaining the Israeli occupation.45

Third Thread: Palestine as a Queer Feminist Issue

In the 2010s, the LGBTQ+ community attracted corporate attention in Japan as a potential market, which motivated the companies to advocate for LGBTQ+ rights protection.46 This business-led, LGBTQ+ advocacy has largely aligned with global trends promoting “universal gay rights.”47 A notable example is the PRIDE Index: established in 2016 in cooperation with Human Rights Watch and leading Japanese companies, the initiative evaluates LGBTQ+ inclusivity in the workplace.48 Companies that earned the Index’s Gold recognition display the logo – featuring two hands clasped in solidarity alongside the phrase “Work with Pride” – on their websites and business cards, as a badge of progressiveness. For many businesses, upholding LGBTQ+ rights has become essential for self-promotion and market expansion.49

While these homonationalist campaigns have brought institutional benefits for LGBTQ+ individuals in Japan, they have also introduced problematic discursive dynamics. Kazuyoshi Kawasaki critiques how such promotion of “universal” gay rights – often embodied by white cisgender gay men – disregards local socio-cultural contexts.50 By intervening, the Western liberal discourse altered the Japanese queer landscape. Additionally, by framing LGBTQ+ rights promotion as “right” and “progressive,” these campaigns have constructed a binary that labels non-conforming others as “backwards” and “wrong” – a simplified narrative that is often conflated with Orientalist discourse targeting Arab and Muslim communities.51

Israel’s pinkwashing campaigns are intimately embedded in this dynamic. Since the 2000s, Israel has heavily invested in its promotion as a gay haven in the Middle East, while depicting Palestine and Arab states contrastingly as “homophobic” and “backwards.”52 This propaganda extended to Japan’s LGBTQ+ rights advocacy. The Israeli embassy’s sponsorship of Tokyo Rainbow Pride (TRP)53 – the biggest LGBTQ+ event in Japan – from 2013 to 2019 is among the clearest examples. In return for this sponsorship, TRP provided booth spaces and stage slots and helped propagate the pinkwashing narratives among the Japanese LGBTQ+ community.

However, informed by Palestinian queer activists and the BDS movement, Japanese queers pushed back against this collaboration. The Feminism and Lesbian Art Working Group (FLA),54 a queer feminist group, submitted multiple open letters to TRP throughout the 2010s, demanding an end to its partnership with the Israeli embassy.55 Not only were these efforts a manifestation of Japanese queers’ intersectional solidarity with Palestine, but they also asserted the Japanese queer autonomy from the LGBTQ+ rights movement. The activists demanded that policymakers heed the call of the local queer community rather than blindly follow the global LGBTQ+ rights agendas.56

Feminist and queer activists were also present at the inaugural meeting of BDS Japan in 2018. The FLA started their engagement with reading and discussion groups in 2014. They began organising political actions in 2015,57 and were among 16 civil society organisations that expressed support for BDS Japan in 2018.58 The synergy between the BDS movement and queer feminist intersectional perspectives transformed the Japan-Palestine solidarity movement. Not only did it expand its scope, but it also fostered critical engagement across queer advocacy and the Palestine solidarity movement, enriching political and ethical consciousness among both circles.

Since October 2023, the genocide in Gaza sent shock waves across the Japanese public and prompted a massive influx of anti-zionist engagement.59 It also galvanised Japanese queers into further action. In February 2024, BDS Japan launched a campaign against the Japanese Ministry of Defence’s potential purchase of Israeli military drones,60 prompting them to divest from Israel.61 The procurement is scheduled to be made through four Japanese companies in the 2026 fiscal year. Japan’s queer community focused on two of the import agencies, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd. and Sumitomo Corporation, both of whom are rated Gold by the PRIDE Index.62 At the 2024 PRIDE Index conference, queer activists demanded that the award be withdrawn, arguing that no company can claim to be LGBTQ+ friendly while facilitating genocide.63

3_queer_placards_in_solidarity_with_palestine._2024.jpg

The front signs read: “Kawasaki Heavy Industries has received the Gold recognition from the PRIDE Index for 6 years!” and “Tokyo Rainbow Pride, cut ties with sponsors complicit in genocide!”

@normalscreen (Instagram), Sign Making for Palestine, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C7b26XUyhXx/

While the government has yet to exclude Israeli suppliers from the supply chain of drone procurement, the growing queer solidarity with Palestine led to a notable shift in Tokyo Pride 2025. In 2024, TRP came under intense scrutiny for its inconsistency between its stated vision of a “future in which everyone can live happily” and its sponsorship practices. In an open inquiry, queer groups urged TRP to clarify its position against violations of Palestinian human rights and to sever ties with BDS-targeted companies.64 TRP’s refusal to answer these demands65 provoked widespread backlash.66 During the 2024 TRP, queer activists organised an alternative demonstration #NoPrideInGenocide to denounce pinkwashing and express solidarity with Palestine.67

4_noprideingenocide.2024.jpg

@hawnuhbrezlow (Instagram), Photograph from the #NoPrideInGenocide Demonstration, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C6BfzIyBu_1/

5_noprideingenocide.jpg

@normalscreen (Instagram), Photograph from the #NoPrideInGenocide Demonstration, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C6VFZyUSHKp

In 2025, TRP rebranded itself as Tokyo Pride and introduced a new sponsorship policy that includes “respect for all beings and human rights” and “zero tolerance for all forms of violence.”68 Although the official statement did not state it explicitly, Kawasaki Heavy Industry and Sumitomo Corporation were excluded from the list of sponsors.69 During the 2025 parade, where almost 15,000 people marched, numerous signs and banners expressing solidarity with Palestine were raised as a powerful reminder that the Palestinian struggle is a queer issue. The transformation in the solidarity movement demonstrates that the Japanese queer feminist community is neither static nor passive. They actively engage with political and ethical concerns in their local and historical contexts and reshape the direction of queer activism in Japan.

6_tokyo_pride_march._2025.jpg

@heasam0322 (Instagram), Photograph from the Tokyo Pride March, 2025. https://www.instagram.com/p/DKrKGo_pb9E/

7_queer_feminist_demonstration._2025.jpg

@sucklaver (Instagram), Queer Feminists with Palestinian Liberation at the Tokyo Pride March, 2025. https://www.instagram.com/p/DKspLJMBorP/

alQaws, a Palestinian grassroots queer group, reiterated that their queerness is “an active part of building our liberation” as Palestinians.70 Nada Elia had similarly declared that justice is indivisible.71 Japanese queer activists echo their belief: they insist that queer liberation must be tied to justice and equality for all oppressed human beings everywhere, including Palestinians.72 Opposing Japanese complicity in pinkwashing and Israeli occupation thus becomes not a choice, but a responsibility. This intersectional solidarity challenges the compartmentalisation of queerness and Palestinian liberation into silos, not only discursively but materially. For those activists, queerness has been fundamental to their commitment to the struggle for the liberation of Palestine.

Fourth Thread: Centring Palestine

Japanese queer engagement in the Palestine solidarity movement has often been informed by queer activists in the US and Europe. For instance, the FLA began their involvement with reading sessions of Israel/Palestine and the Queer International by Sarah Schulman.73 This autobiographical account traces her journey as a queer feminist ally in the Palestinian struggle.74 Schulman’s journey encouraged FLA members to imagine ways of forging solidarity with the Palestinian resistance as queer feminists.75

Drawing inspiration from “Western” literature and movements – or learning about activism in the Global South through Western framework – is not uncommon for Japanese feminists, queer activists, or leftists more broadly.76 It is important here to not lose sight of the power dynamics at play. As Nada Elia notes, white feminists often decide whose struggle is on the agenda and whose isn’t.77 In those contexts, the Palestinian struggle is often read through the romanticised lens of past queer activism in the US and Europe, as Nayrouz Abu Hatoum and Ghadia Moussa observe.78 Hence, solidarity practices must centre the lived experiences and political demands of those who are directly impacted.79

Since October 2023, centring Palestinian voices has become a priority in the Japan-Palestine solidarity movement.80 Feminist queer activists like Natsuki Minamoto translated Instagram reels posted by Palestinians – both from Palestine and its diaspora – into Japanese.81 In the immediate aftermath of October 7, a decontextualised narrative that demonised Palestinians dominated Japanese media, and Minamoto’s translation practices proved crucial in shedding light on the 75-year-long history of forced displacement and occupation in Palestine.

Such efforts aimed at amplifying Palestinian voices have also cultivated connections between Japanese activists and Palestinians living in Japan. The number of the Palestinian population in Japan is small – estimated at 100 as of 2024.82 But this “mighty”83 community, in the words of Palestinian activist Hanin Siam,84 have long been dedicated to raising awareness of the Palestinian struggle, especially through the PLO office in Tokyo.85 However, since 2023, a more grassroots engagement has overseen the launch of the Instagram account “Palestinians of Japan,”86 where the Palestinian community takes control of the narrative on social media and at protests. This shift in the landscape made way for more relational and reciprocal forms of solidarity between Palestinian and Japanese activists.

Cultural and artistic expression is one of the key sites such mutual engagement flourishes. In November 2023, Palestinians and Arabs residing in Japan initiated “Tears for Palestine,” which invites people to paint red tears on a white banner while the names of martyrs in Gaza are read aloud.87 The act may appear simple but is an active participation in protest: perceived as daunting for decades, political engagement becomes reachable for a broader Japanese public.88 Tears for Palestine gained traction and has been practiced in multiple cities across Japan, as a material manifestation of a collective mourning and protest for Palestine. The impactful visual archive of the numerous red tears garnered further attention in social media posts and exhibitions.

8_tears_for_palestine._2023.jpg

@omou_palestine (Instagram), Tears for Palestine, 2023. Photograph by @sucklaver. https://www.instagram.com/p/C0HD1qoSMHm

Aesthetics as a vehicle of social movement takes on a specific significance in Japan, where political activism has been historically repressed.89 The tactics that gradually developed during the “invisible civil society” era have now adapted to contemporary tools and platforms by younger generations.90 In August 2024, Danny Jin,91 a Palestinian Japanese rapper, released his new song “Boycott.”92 Rhyming in Japanese and English, the defiant sound calls for boycotting companies complicit in genocide in Gaza. In an interview with AJ+, he explains, “[I]f I make good music, by[sic] little by little, I can inform about Palestine.”93 Kenichiro Egami,94 a scholar of arts and activism, observes a similar tactic in the visual arts: he notes that images and paintings expressing solidarity with Palestine were constructed with a careful combination of familiar kawaii (cute) designs and clear political messages.95 This fusion communicates the gravity and urgency of the Palestinian cause in direct, yet approachable ways.

Queer activists have also used their aesthetics to amplify their activism for Palestine, using creative placards, bodily performances,96 and popular anime culture. For instance, in early 2024, an Instagram post of the Sailor Moon adaptation97 repurposed the iconic symbol of a girl who fights for love and justice into an urgent call for a ceasefire in Gaza. Inspired by the widely circulated post, a parody of the Sailor Moon theme song “Moonlight Legend” was created, with the rewritten lyrics calling for Palestinian liberation.98 This performance became one of the highlights of #NoPrideInGenocide demonstration.99

9_moonlight_legend._2024.jpg

@hawnuhbrezlow (Instagram), Activists Singing the Parody “Moonlight Legend” at the #NoPrideInGenocide Demonstration, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C6BfzIyBu_1/

It is important to note that these cultural engagements did not exist in isolation, as they targeted not only political engagement but also political actions. Aware of the limitations of cultural activism,100 artivists often called for other forms of involvement alongside artistic expressions, such as fundraising or boycotting companies complicit in genocide. In other words, cultural expression is not a goal in itself, but an entry point to political transformation. By incorporating familiar and popular cultural forms, queer feminist activists are building a more approachable political space for Palestine solidarity, which, ultimately, aspires to collective actions for Palestinian liberation.

Final Remarks: Lessons from Palestine

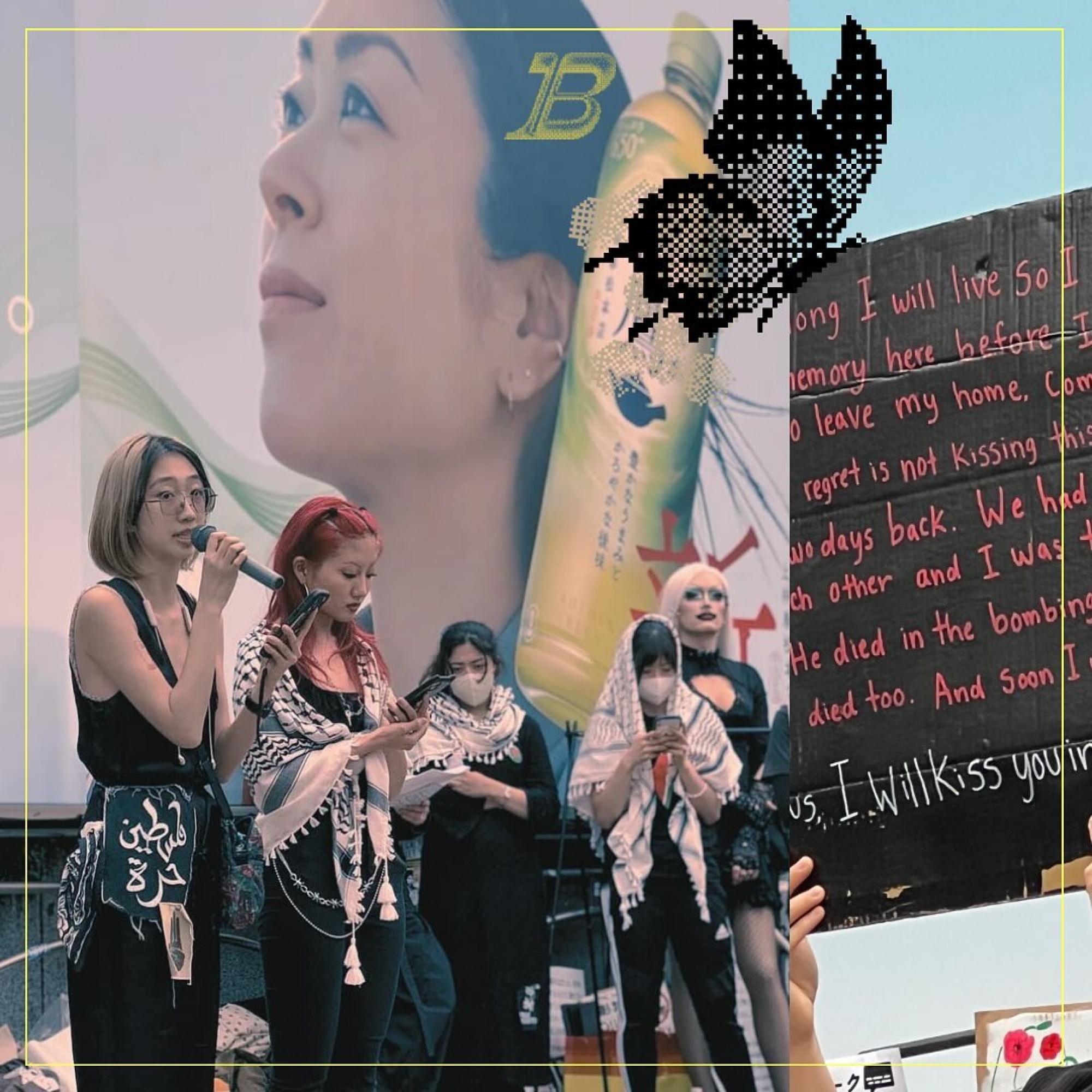

While the centring of Palestinian voices must form the foundation of solidarity activism, it is equally vital that Japanese queer activists reflect on their own history in light of the Palestinian struggle.101 During the 2024 #NoPrideInGenocide protest, Uhi,102 a queer Zainichi Korean,103 shared the story of Bong-gi Bae,104 a Zainichi Korean woman and survivor of systematic rape by the Japanese army during the WWII. Bong-gi Bae was brought to Okinawa in 1944, one year before the brutal ground battle was fought on the island. As a “comfort woman,”105 Bae was forced to sexually serve Japanese soldiers. Even after the war, she had to endure the same treatment at a US military camp as Japan gave up the comfort women to US soldiers to “protect” Japanese women from sexual violence. Through the story, Uhi highlighted106 how colonialism, racism, and sexism are deeply intertwined and how these structural oppressions parallel the atrocities unfolding in Gaza.

10_uhi_noprideingenocide.jpg

A collage featuring Uhi (left) at the 21 April protest, a sign from the protest with a Queering the Map post (right), and an image of black butterfly (top). Yellow butterflies symbolise survivors of sexual violence by the Japanese Imperial Army. The Black butterfly, in this context, symbolises solidarity with Palestine.

@dee.gml (Instagram), Collage of Photographs from the #NoPrideInGenocide Demonstration, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C6Dm_DVyrwc

As they challenge Israeli settler colonialism, queer activists are compelled to face Japan’s (and their) own colonial history. To be in solidarity with Palestine also means extending solidarity to and from other marginalised communities in Japan, including the Buraku, Ainu, Ryukyuan, and Zainichi Korean populations.107 This development demonstrates the growing recognition of the overarching structures of oppression that shape different struggles. It is this intersectional consciousness that forges solidarity beyond geographical, social, and any other borders.

By connecting the Palestinian struggle with local histories of oppression, this new momentum is fostering more reflexive, inclusive, and ethical practices. For instance, BDS Japan now stresses that the Palestinian struggle is an intersectional one that encompasses colonialism, capitalism, patriarchy, gender norms, ableism, and more. The struggles of queer activists are not isolated issues but part of broader and structural systems of oppression. They have to continually learn from one another and reflect on their practices, in an ongoing process that will never be fully completed. But it is through this continuous reflection and mutual learning that they commit to a dynamic, transnational, and interconnected movement that transcends borders in the fight for the liberation of Palestine.

Solidarity Archive

[resources are in Japanese, unless stated otherwise]

Japanese Red Army and the PFLP (1970s)

During the global anti-imperialist era, early Japanese–Palestinian revolutionary alliances were formed.

- Full documentary of Sekigun-P.F.L.P.: Sekai Senso Sengen (World War Declaration) [赤軍-P.F.L.P.: 世界戦争宣言] [with English subtitles]: https://archive.org/details/sekigunpflpsekaisensosengentheredarmypflpdeclarationofworldwar

Sabreen Japan Tour (1992)

Sabreen toured Tokyo, Kyoto, and Hiroshima, introducing Japanese audiences to Palestinian political music.

- Photographs from The Palestinian Museum Digital Archive [in English]: https://palarchive.org/index.php/Search/objects/search/sabreen%2C%20japan%20tour/sort/Date/direction/asc/lang/en_US

- Tsuyoshi Okada’s memoir of the tour: http://am.jungle-jp.com/song01_3.html

BDS Japan (2018-ongoing)

BDS Japan was established in 2018 with 16 Japanese groups’ support. in response to the 2005 BDS call.

- Leaflet for the BDS Japan inaugural meeting: https://bdsjapan.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/bdse799bae8b6b3e99b86e4bc9ae8b387e69699.pdf

- BDS Japan Bulletin: https://bdsjapanbulletin.wordpress.com/

- Leaflet promoting BDS actions: https://www.instagram.com/p/DCPBJEiSEfu/

Anti-Pinkwashing Campaign against Tokyo Rainbow Pride (2018-ongoing)

Queer feminist activists pressured Tokyo Rainbow Pride to sever ties with the Israeli embassy and to stand against pinkwashing.

- Feminism and Lesbian Art Working Group’s portal, in which their open letters are archived: https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/

- Instagram post calling to mobilise against TRP’s sponsorship by BDS-targeted companies: https://www.instagram.com/p/C4kJJM5Sjyx/

Anti-Drone Purchase Campaign (2024-ongoing)

Led by the Network Against Japan Arms Trade and the Association of National Defence Academy Alumni Against Genocide, Japanese collectives are mobilising against import agencies and the Ministry of Defence’s consideration of Israeli-made drones, arguing that they are weapons tested on Palestinians and used in genocide.

- BDS Japan’s call for actions against import of Israeli drones: https://bdsjapanbulletin.wordpress.com/2024/09/21/call-for-action-against-import-of-israeli-drones/

- Negotiation with the Defence Ministry, 22 May 2025: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7IJqEanV1Y0

- Protest at the shareholders’ meeting of Kawasaki Heavy Industry, 25 June 2025: https://kojiskojis.hatenablog.com/entry/2025/06/25/230023

- Speech by Takamori Hirayama (@shanshan96521 on Instagram) at Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd.: https://www.instagram.com/p/C8_WhQ_yHp1/

Anti-Pinkwashing Campaign against the PRIDE Index (2024-ongoing)

Activists criticised the PRIDE Index for awarding the “Gold” recognition to Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd. and Sumitomo Corporation despite their complicity in Israel’s military violence.

- Post calling for protests against pinkwashing by the PRIDE Index: https://www.instagram.com/p/DCTZ7pspYER/

- Excerpts from the protest against the PRIDE index, November 14 2024: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AYaIyHI0Yxw; https://www.instagram.com/p/DCWiTxayVqQ/?img_index=8

#NoPrideInGenocide Demonstration (2024)

On 21 April 2024, queer activists hosted an alternative protest in Shibuya in opposition to the 2024 Tokyo Rainbow Pride’s pinkwashing.

- Images from the protest [bilingual]: https://www.instagram.com/p/C6BfzIyBu_1/

- Video documentation of the protest: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xsSHKedap3w

- Zine collecting available protest speeches [bilingual]: https://waifu.stores.jp/items/66bc542657ef7202849807fa

Solidarity for Palestine at the 2025 Tokyo Pride (2025)

There was a stall in solidarity with Palestine at the 2025 Tokyo Pride, and Palestinian flags and banners for Palestine appeared during the march on June 8, 2025.

- BDS statement on the changes in Tokyo Pride’s sponsorship [in English]: https://www.instagram.com/p/DJuRxzKJijV/

- “loneliness books” stall in solidarity with Palestine: https://www.instagram.com/p/C6ANYn9yKnT/

- Video from the Pride march: https://www.instagram.com/p/DKqNgEjhsvG/

- Images from the Pride march: https://www.instagram.com/p/DKqzf0rpOha/

Grassroots Translations of Palestinian Voices (2023-ongoing)

Individuals have taken to translate posts from Palestinian journalists, families, and activists into Japanese in order to expand access to Palestinian narratives.

- Instagram page of Natsuki Minamoto: https://www.instagram.com/inkyano_geji/

- Minamoto’s translation of @byplestia’s report (originally posted by @middleeasteye): https://www.instagram.com/p/CyaeTVHSfMR/

- Minamoto’s translation of a video by @salma.shawa: https://www.instagram.com/p/CycgvQVS_sT/

- Minamoto’s translation of a video by @wizard_bisan1: https://www.instagram.com/p/CysAMFLy22b/

- The Instagram page “Palestine in Japanese:” https://www.instagram.com/palestine.in.japanese/

Palestinians of Japan (2023-ongoing) [bilingual]

Palestinians living in Japan launched an Instagram account and have organised and joined protests to amplify Palestinian voices.

- Account run by Palestinians in Japan: https://www.instagram.com/palestinejapan/

- Selected speeches:

@aida.makes, 20 December 2023: https://www.instagram.com/p/C1eoNGpSMpg/

@itendtotravel, 13 January 2024: https://www.instagram.com/p/C2D9cshy2Q3/

@hanin.gaza.jp, 11 February 2024: https://www.instagram.com/p/C3RUKRevpZb/

Tears for Palestine Collective (2023-ongoing)

Initiated by Palestinians and held in multiple Japanese cities, it consists of public banner-painting during protests while names of martyrs are being read.

- Promotion of an exhibition featuring Tears for Palestine banners [bilingual]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xCou2WCgTM4

- Selected images and videos:

[bilingual] https://www.instagram.com/p/C0HD1qoSMHm/

[in English] https://www.instagram.com/p/Cz0CSFTvWdJ/

[in English] https://www.instagram.com/p/C012HlMSRSU/

Danny Jin (ongoing)

Danny Jin is a Palestinian-Japanese rapper who creates political songs about Palestine, Japan’s complicity, and calls to boycott.

- “Boycott” music video, 1st September 2024 [bilingual]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bf77vvUSfqQ

- “War and Death,” performed at a protest in January 2024: https://www.instagram.com/p/C2D6mF1yhyT/

- Interview with Danny Jin with AJ+, 4 September 2024 [in English]: https://www.instagram.com/reel/C_gER7uOhnG/

Uhi’s Speech at the #NoPrideInGenocide (2024)

Uhi’s speech connected Japan’s WWII sexual violence towards Zainichi Korean survivors with Israel’s violence in Gaza.

- Uhi speaking at #NoPrideInGenocide protest, 21 April 2024: https://www.instagram.com/p/C6bIHnBPQOH/

- Images and transcript from Uhi’s speech: https://www.instagram.com/p/C6Dm_DVyrwc/

Full transcript of Uhi’s speech [bilingual]: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1cTKg4HqCYbGXJWImypZg2YBU_iCkFKEIXVIDul7-9x8/

- 1. https://japan.kantei.go.jp/constitution_and_government_of_japan/constitution_e.html

- 2. https://www.jcp.or.jp/english/

- 3. Steinhoff, 2017:165-166

- 4. Coogan and Derichs, 2023:16

- 5. ibid.:15-17

- 6. At the its 6th Party Conference in 1954, the JCP acknowledged that it had placed its effort in “a wrong direction” by endorsing armed struggle. The party also expressed concern over its loss of parliamentary seats in the 1952 election and announced a strategic shift toward gaining popular support and building coalition with other parties such as the Social Democratic Party. https://undou.net/blog/2024/%e6%97%a5%e6%9c%ac%e5%85%b1%e7%94%a3%e5%85%9a%e3%80%8c%e7%ac%ac6%e5%9b%9e%e5%85%a8%e5%9b%bd%e5%8d%94%e8%ad%b0%e4%bc%9a%e3%80%8d%ef%bc%88%e5%85%ad%e5%85%a8%e5%8d%94%ef%bc%89%e6%b1%ba%e8%ad%b0-%e3%80%8c/

- 7. Steinhoff, 2024:36

- 8. Coogan and Derichs, 2023:19

- 9. Randall, 2023a:360-361

- 10. Randall, 2023b: 88-89

- 11. ibid.:86

- 12. Randall, 2023a:362-363

- 13. Randall, 2023b:86-87

- 14. Atshan, 2024:442

- 15. Igarashi, 2021:229-230

- 16. Andrews, 2016:137

- 17. Schieder, 2021:2-3; Steinhoff, 2012:63-64

- 18. Schieder, 2021:12; Andrews, 2016:137

- 19. Morishita, 2023

- 20. Randall, 2023b:82; http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/may/29/newsid_2542000/2542263.stm

- 21. Igarashi, 2021:228; https://www.nippon.com/en/in-depth/d00776/

- 22. Qumsiyeh, 2011:4-10

- 23. Slater and Steinhoff, 2024:50-52

- 24. ibid.:52

- 25. Steinhoff, 2024:42

- 26. Igarashi, 2021:228-229

- 27. Steinhoff, 2024:42

- 28. ibid.:43

- 29. ibid.:43-44

- 30. https://sabreen.org/about-music-band

- 31. Okada, 1995

- 32. ibid.

- 33. Matushima, 1998

- 34. Okada, Yakushige, and Tanami, 2002:97-100; https://www.jica.go.jp/english/activities/schemes/volunteer/index.html

- 35. ibid.:101-102

- 36. The cultural exchange started with the first Japanese translation of Ghassan Kanafani’s works published in 1974. See: Okada, Yakushige, and Tanami 2002:93-94; Ross 2024.

- 37. https://f.hatena.ne.jp/chairs_story/20160305154507; https://f.hatena.ne.jp/chairs_story/20160305154457

- 38. https://www.michelkhleifi.com/en-films/canticle-of-the-stones

- 39. Matushima, 1998

- 40. Tsuyoshi Okada, Yoshihiro Yakushige, and Aoe Tanami trace the shifting engagements in response to the changing political developments, including the Yom Kippur War, the Sabra and Shatila Massacre, the First Intifada, and the Oslo Accords (2002:94-107).

- 41. https://bdsmovement.net/call

- 42. Hussein, 2015:151

- 43. https://www.facebook.com/palestine.forum.japan

- 44. Okada, Yakushige, and Tanami, 2002:107

- 45. Hussein, 2015:151

- 46. Kawasaka and Würrer, 2024:6-7

- 47. Kawasaka, 2024:24

- 48. https://workwithpride.jp/pride/report2016.pdf

- 49. Kawasaka and Würrer, 2024:6-7

- 50. Kawasaka, 2024:24-26; 29-30

- 51. Rao, 2014:200-202

- 52. Kablawi, 2024.

- 53. https://pride.tokyo/#en

- 54. For the FLA’s English website, see: http://selfishprotein.net/cherryj/index.html. It has not been updated since 2015, as they have since transitioned to using Tumblr as their primary platform.

- 55. https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/tagged/trp

- 56. For example, in their 2016 complaint letter, the FLA asserted that the Japanese queer community is not to be underestimated: https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/737941702584713216/trp2024-bds-letter

- 57. As per their Facebook platform “Queering Ordinary LGBT/ Feminist and LGBT Association Making Placards or More:” https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100064391660846

- 58. https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/117078759471/lgbt-2015-4/amp

- 59. Takahashi, 2024

- 60. The plan, in place since 2022, gained public attention in late February 2024 following negotiations between the Ministry of Defence and Japanese anti-militarism activists. The four import agencies involved are Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd., Sumisho Aero-Systems Corporation (a subsidiary of Sumitomo Corporation), Nippon Aircraft Supply Co., Ltd., and Kaigai Corporation. See: The Yomiuri Shimbun, 2022; Kunizaki, 2024.

- 61. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20240531-pro-palestine-protests-in-japan-demand-divestment-from-israel/

- 62. https://workwithpride.jp/report/

- 63. 14 Nov. No! Pinkwashing! Action: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L0-vDUH33f8

- 64. https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/737941702584713216/trp2024-bds-letter

- 65. https://tokyorainbowpride.org/news/20240315/2183/

- 66. https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/740022720990953472/trp2024-noresponse

- 67. https://www.instagram.com/p/C5-0mHkS0iO; https://www.instagram.com/p/DKqNgEjhsvG/

- 68. https://pride.tokyo/sponsors/

- 69. https://www.instagram.com/p/DJXBWzHSwoQ/; https://www.instagram.com/p/DJuRxzKJijV/

- 70. https://alqaws.org/news/Reflecting-on-Queerness-in-Times-of-Genocide

- 71. Elia, 2017:60

- 72. https://www.instagram.com/p/DCWiTxayVqQ/

- 73. https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/117078759471/lgbt-2015-4/amp

- 74. Schulman, 2012:66

- 75. http://selfishprotein.net/cherryj/2014/Schulman.html

- 76. Knaudt, 2020:417; Hirokawa, 2016:57; Shimizu, 2020:89; https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/612468639048810496/%E6%B4%BB%E5%8B%95%E8%A8%98%E9%8C%B2%E3%83%AA%E3%83%B3%E3%82%AF-2001-2014%E5%B9%B4

- 77. Elia, 2017:48-49

- 78. Abu Hatoum and Moussa, 2018:179

- 79. https://www.instagram.com/p/DC1lfC-xICm/

- 80. https://bdsjapanbulletin.wordpress.com/bds-japan-bulletin%e3%81%ab%e3%81%a4%e3%81%84%e3%81%a6

- 81. Nakata, 2024

- 82. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00250012&tstat=000001018034&cycle=1&year=20240&month=12040606&tclass1=000001060399

- 83. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L8AQtgcsoZc

- 84. https://www.instagram.com/hanin.gaza.jp/

- 85. Okada, Yakushige, and Tanami, 2002:94-97

- 86. https://www.instagram.com/palestinejapan/

- 87. https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20231120/p2a/00m/0na/018000c; https://www.davidlundin.me/news/2023/tokyo-tears-for-palestine; https://www.milleworld.com/tears-for-palestine-an-alternative-protest-with-roots-in-japan/

- 88. Egami, 2024

- 89. Slater and Steinhoff, 2024:58

- 90. ibid.:56-58

- 91. https://www.instagram.com/dannyjin_hojicha/

- 92. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bf77vvUSfqQ

- 93. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C_gER7uOhnG/

- 94. https://www.instagram.com/kenichiro_egami/

- 95. Egami, 2024

- 96. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MPlFWOAR_Ls

- 97. https://www.instagram.com/p/C2lPWJNokgO/

- 98. https://www.instagram.com/p/C5-0mHkS0iO/

- 99. https://www.instagram.com/p/C6EzpVMrr1e/

- 100. Slater and Steinhoff, 2024:58-59

- 101. As reflected in works such as: Atshan and Moore, 2014:694-696

- 102. https://www.instagram.com/dee.gml/

- 103. People with ethnic Korean roots who came to Japan as a result of Japanese colonial rule.

- 104. https://www.international.ucla.edu/cks/care/comfortwomen_speakup/267631

- 105. https://international.ucla.edu/cks/care

- 106. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1cTKg4HqCYbGXJWImypZg2YBU_iCkFKEIXVIDul7-9x8/

- 107. https://minorityrights.org/country/japan/

Abu Hatoum, Nayrouz, and Moussa, Ghadia. “Becoming through Others: Western Queer Self-Fashioning and Solidarity with Queer Palestine.” In Rio Rodriguez (ed), Queering Urban Justice: Queer of Colour Formations in Toronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018, 169–186.

alQaws. “Reflecting on Queerness in Times of Genocide.” alQaws for Sexual & Gender Diversity in Palestinian Society, June 6, 2024. https://alqaws.org/news/Reflecting-on-Queerness-in-Times-of-Genocide

Andrews, William. Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture, from 1945 to Fukushima. London: Hurst & Company, 2016.

Atshan, Sa’ed, and Moore, Darnell L. “Reciprocal Solidarity: Where the Black and Palestinian Queer Struggles Meet.” Biography 37:2 (2014): 680–705.

Atshan, Sa’ed. “Queer Masculinity and Global Palestine Solidarity: The Art of Yusef Audeh”,” Men and Masculinities 27:4 (2024): 428–447.

Barat, Frank. “Voices of Solidarity: GAZA and JAPAN: a conversation with Hanin Siam and Neo Sora.” YouTube, September 12, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L8AQtgcsoZc

Coogan, Kevin, and Derichs, Claudia. Tracing Japanese leftist political activism (1957-2017): The Boomerang Flying Transnational. New York: Routledge, 2023.

Egami, Kenichiro. “Japanese Activism in Japan within Palestine Solidarity Movement [パレスチナ連帯運動に見る日本国内のアート・アクティヴィズムとは].” Bijutsu Techo [美術手帖], June 23, 2024. https://bijutsutecho.com/magazine/insight/29014

Elia, Nada. “Justice is Indivisible: Palestine as a Feminist Issue.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 6:1 (2017): 45–63.

Feminism and Lesbian Art Working Group. “Course of Events of Queering Ordinary LGBT until April 2015 [「フツーの LGBTをクィアする」経緯(2015年4月まで)].” Tumblr, April 2015. https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/117078759471/lgbt-2015-4/amp

Feminism and Lesbian Art Working Group, “Links to Activity Records (2001 - 2014) [活動記録リンク (2001~2014年)].” Tumblr, March 13, 2020. https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/612468639048810496/%E6%B4%BB%E5%8B%95%E8%A8%98%E9%8C%B2%E3%83%AA%E3%83%B3%E3%82%AF-2001-2014%E5%B9%B4

Feminism and Lesbian Art Working Group. “NPO Tokyo Rainbow Pride Refused to Answer the Open Inquiry: Make Your Voice Heard by TRP! [NPO法人東京レインボープライドが公開質問状に「回答拒否」。みなさんの声をTRPに届けてください!!].” Tumblr, January 20, 2024, https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/740022720990953472/trp2024-noresponse

Feminism and Lesbian Art Working Group. “Open Enquiry to Tokyo Rainbow Pride 2024 Regarding Sponsorship from the Israeli Embassy and Corporations Targeted by the BDS Movement [東京レインボープライド2024へのイスラエル大使館とBDS対象企業からの協賛についての公開質問状].” Tumblr, December 28, 2023. https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/737941702584713216/trp2024-bds-letter

Feminism and Lesbian Art Working Group. “Protest against Talula Bonet’s DQ Show and Booth Sponsored by the Israeli Embassy at Tokyo Rainbow Pride [東京レインボープライド におけるイスラエル大使館肝入りのタルラ・ボネットDQショーとブース出展に抗議する].” Tumblr, May 7, 2016. https://feminism-lesbianart.tumblr.com/post/737941702584713216/trp2024-bds-letter

Feminism and Lesbian Art Working Group. “Reading Sarah Schulman “Israel/Palestine and the Queer International” [サラ・シュルマン「イスラエル/パレスチナとクイア・インターナショナル」読書会].” Selfish Protein, June 22, 2014. http://selfishprotein.net/cherryj/2014/Schulman.html

Hirokawa, Shuhei. “The Roles and Limitations of ‘Learning-Action’ in the Sexual Minorities Movement in Japan, Focusing on the Ideas of Minami Teishiro.” Jenda Shigaku [Gender History Studies] 12 (2016): 51–60.

Hussein, Cherine. The Re-Emergence of the Single State Solution in Palestine/Israel: Countering an Illusion. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. Japan, 1972: Visions of Masculinity in an Age of Mass Consumerism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

Kablawi, Rami. “Pinkwashing 101: How Israel Turned Gay Pride into an Occasion for Oppression.” The Forge, June 21, 2024. https://forgeorganizing.org/article/pinkwashing-101-how-israel-turned-gay-pride-occasion-oppression

Kawasaka, Kazuyoshi, and Würrer, Stedan. “Introduction: A New Age of Visibility? LGBTQ+ Issues in Contemporary Japan.” In Kazuyoshi Kawasaka and Stefan Würrer (eds), Beyond Diversity: Queer Politics, Activism, and Representation in Contemporary Japan. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press, 2024, 1–20.

Kawasaka, Kazuyoshi. “The Progress of LGBT Rights in Japan in the 2010s.” In Kazuyoshi Kawasaka and Stefan Würrer (eds), Beyond Diversity: Queer Politics, Activism, and Representation in Contemporary Japan. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press, 2024, 21–38.

Knaudt, Till. “A Farewell to Class: The Japanese New Left, the Colonial Landscape of Kamagasaki, and the Anti-Japanese Front (1970-1975).” The Journal of Japanese Studies 46:2 (2020): 395–422.

Kunizaki, Machi. “Import of Israeli Drones ‘Crosses the Line’: Why a National Defence Academy Graduate Opposes Under His True Identity [防衛省のイスラエル製ドローン輸入は「一線を越える」。防衛大卒業生が実名で反対する訳].” Huffington Post Japan, June 28, 2024. https://www.huffingtonpost.jp/entry/story_jp_6678dba5e4b03378e8dcabc9

Kunizaki. Machi. “Message to ‘Turn a Blind Eye to the Genocide’: An Expert Warns of Defence Ministry’s Consideration to Purchase Israeli ‘Attack Drones’ [「虐殺に目をつぶるというメッセージ」防衛省のイスラエル製「攻撃用ドローン」購入検討、専門家が警告].” Huffington Post Japan, March 28, 2024. https://www.huffingtonpost.jp/entry/story_jp_66010884e4b09f0d72588b84

Matushima, Hiroshi. “The Meeting of Hearts with Sabreen [パレスチナのサブリーンとの心の出会い].” Yorozubampo [萬晩報], October 14, 1998. https://yorozubp.com/9810/981014.htm

Morishita, Kae. “Fusako Shigenobu, Former Leader of the Japanese Red Army, Expressed Her Remorse: The Tragic Death of a Close Friend and Misogyny [重信房子・元日本赤軍最高幹部が語る悔恨 親友の非業の死と女性蔑視].” The Asahi Shimbun, July 12, 2023. https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASR7C65XGR6GOXIE097.html

Nakata, Maya. “‘There Is No Way to Stay Silent about Palestine’: Why a Queer Feminist Speaks Out [「パレスチナの現状に何も言わないなんてありえない」フェミニストでクィアの私が声を上げる理由].” Huffington Post Japan, February 23, 2024. https://www.huffingtonpost.jp/entry/story_jp_65d6b605e4b0b65d69219b65

Okada, Tsuyoshi. “Considering “Death of the Prophet” [「預言者の死」に向き合って].” Dreams We Could Not See in Life [生きているうちにみられなかった夢を], September 27, 1995. http://am.jungle-jp.com/song01_3.html

Okada, Tsuyoshi, Yakushige, Yoshihiro, and Tanami, Aoe. “Solidarity Movement and Anti-War: Attempt of History of Palestine Solidarity Movement [連帯運動と反戦思想: パレスチナ連帯運動史への試み].” Impaction 129 (2002): 86–113.

Qumsiyeh, Mazin B. Popular Resistance in Palestine: A History of Hope and Empowerment. London: Pluto Press, 2011.

Randall, Jeremy. “Global Revolution Starts with Palestine: The Japanese Red Army’s Alliance with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 43:3 (2023): 358–369.

Randall, Jeremy. “Shigenobu Fusako: From Japan to Palestine in World Revolution.” In Marral Shamshiri and Sorcha Thomson (eds), She Who Struggles: Revolutionary Women Who Shaped the World. London: Pluto Press, 2023, 81–94.

Rao, Rahul. “Queer Questions.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 16:2 (2014): 199–207.

Ross, Julian. “Tokyo Reels: The Solidarity Image.” Afterall, September 10, 2024. https://www.afterall.org/articles/tokyo-reels-the-solidarity-image/

Schieder, Chelsea Szendi. Coed Revolution: The Female Student in the Japanese New Left. Durham: Duke University Press, 2021.

Schulman, Sarah. Israel/Palestine and the Queer International. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Sekigun-P.F.L.P.: Sekai Senso Sengen [赤軍-P.F.L.P. 世界戦争宣言]. Directed by Masao Adachi and Koji Wakamatsu, 1971. Japan: Internet Archive, 2019.

Shimizu, Akiko. “‘Imported’ Feminism and ‘Indigenous’ Queerness: From Backlash to Transphobic Feminism in Transnational Japanese Context.” Jenda Kenkyu [Gender Studies] 23 (2020): 89–104.

Slater, David H., and Steinhoff, Patricia G. “Rejecting the Radical New Left: Transformations in Japanese Social Movements.” Soocieta Mutamento Politica 15:29 (2024): 49–61.

Steinhoff, Patricia G. “Japan: Student Activism in an Emerging Democracy.” In Meredith L. Weiss, and Edward Aspinall (eds), Student Activism in Asia: Between Protest and Powerlessness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012, 57–78.

Steinhoff, Patricia G. “Transforming Invisible Civil Society into Alternative Politics.” In David H. Slater and Patricia G. Steinhoff (eds), Alternative Politics in Contemporary Japan: New Directions in Social Movements. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2024, 34–63.

Steinhoff, Patricia G. “Transnational Ties of the Japanese Armed Left: Shared Revolutionary Ideas and Direct Personal Contacts.” In Alberto Martin Alvarez and Eduardo Rey Tristan (eds), Revolutionary Violence and the New Left: Transnational Perspectives. Oxford: Routledge, 2017, 163–182.

Takahashi, Saul. “Japan: Inching Toward Palestine?” Arab Center Washington DC, October 16, 2024. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/japan-inching-toward-palestine/

The Yomiuri Shimbun. “Attack Drones to Be Tested for Defense of Remote Islands.” The Japan News, September 14, 2022. https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/politics/defense-security/20220914-58237/