The Witches of the Unwanted Colonies

Sve su to vještice (It’s all Witches) is the author of the original memes created by creatively intervening on existing photographs taken from Pinterest, YouTube, and Tumblr platforms. All original photos can be found on Pinterest, where the author of the creative work has found and re-archived them for non-commercial use. However, in order to fairly credit original work, the credits of the original photographs, used for creative inspiration and intervention, were extracted to the best possible extent through online research.

9.png

Screenshot, Trailer for Quentin Tarantino’s film “Deathproof,” 2007

What does it mean to be a feminist in an unwanted colony,1 a place deemed unworthy of territorial conquest or even integration into a European polity, yet too dangerous or unstable to be left alone? I explore this question through a conversation with Hana Ćurak, a sociologist and artivist from Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, a feminist meme-blogger, and the creator of a multimedia project “It’s All Witches” – “a platform for identification and subversion of patriarchal particularities in the everyday.”2 Currently residing in Berlin, Germany, where she works as a media consultant, Hana has also produced and co-produced art projects and exhibits, recorded podcasts and video conversations with feminist scholars, writers, and filmmakers, and organized prescient public discussions with critical ex-Yugoslav intellectuals about the state of politics in the region and beyond.

The wars of the 1990s still cast a long shadow on political but also everyday life in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ever since the Dayton Peace Agreement, which ended the war in 1995, Bosnia has been, as David Chandler put it, “faking democracy”3 and its own sovereign status. The country is a de facto protectorate of the international community, whose powers are vested in the Office of the High Representative and the Peace Implementation Council which overseas its work. At the same time, the ethno-nationalist straight-jacket of Dayton’s institutional architecture ensures that the same dynamics that had led to the war are perpetuated through party politics and elections. Bosnia is thus neither sovereign nor not, neither a colony nor an independent country. While no longer ghettoized through the European Union’s restrictive visa regimes, it is also not on a clear path towards European integration. The rest of the former Yugoslavia and the Balkans are similarly politically checkered, with some states in and some out of the EU and NATO. As in much of its history, the Balkans is simultaneously a zone of contestation and of neglect by the great powers, and the contradictory effects of this pull and push have only intensified since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022.

Gender relations both reflect and reconstitute these international hierarchies. Western Balkans, and Bosnia and Herzegovina in particular, are now places with the lowest gender-equity scores in Europe.4 Participation of Yugoslav women in anti-fascist and revolutionary struggles of World War II, their significant achievements under socialism, engagement in the Non-Aligned Movement, and the extreme violence against women during the wars of the 1990s are all but forgotten.5 A complex scaffolding of international supervision promotes gender-equity legislation and measures, which do not seem to reach women in their everyday lives. Civil society, including gender-related activism, is professionalized and captive to international donors, while women continue to carry the invisible burden of child-rearing and care for the elderly, informal work, and household provisions. As a result, birth rates are declining and massive exodus to the West is emptying and aging the state, much as in other parts of Eastern Europe.6 The manliness of the Dayton Peace Agreement, negotiated without any women, is deeply entrenched, and reinforced through neoliberal depletion of public services, especially education, health care, culture, and the arts.7

In that context, social media projects and art interventions, which Hana Ćurak has produced or been involved with, serve as rare “attempts to encourage women to identify and take agency over their own life.”8 Hana’s witches take their inspiration from anti-nationalist Yugoslav feminists who raised their voices against the war in the 1990s only to be charged as traitors, exposed to media-lynching, and literally labeled as “the witches.”9 But Hana’s memes do not replicate feminist politics as intellectual positioning only. Instead, by using all available social media platforms (Facebook and Instagram especially, where the witches have tens of thousands of followers) her memes domesticate and localize feminism, and by challenging its possible elitism turn it into a tool of everyday survival, humorously coping with and undermining patriarchy. Most of Hana’s memes feature famous feminist figures or women “celebrities” engaged in the most colloquial, banal, patriarchal everyday exchanges. Many are, therefore, non-translatable, as their power derives from this creative claiming of ordinary language as channeled via Simone De Beauvoir, Virginia Wolf, Betty Friedan, or even Michelle Obama and Melania Trump. The memes reach out to women who might never identify as feminists, and they find them in spaces where political and economic circumstances otherwise entrap them.

The conversation with Hana Ćurak about the witches is, therefore, a provocation to rethink the feminist past and the meaning of its legacy in contemporary unwanted colonies which, like Bosnia, continue to linger in the nether-lands of international tutelage and utmost disregard for their humanity.

Aida: Hana, could you describe for the readers the world you live in? What defines your world? What constitutes its boundaries, what enables your freedom and your mobilities?

Hana: I am very mobile and almost ephemeral, and my world is increasingly “feminine” and feminist. There’s not so much space for hegemonic masculine knowledge in it. I unfortunately tend to ignore and forget that.

My world is constituted more by figurations than boundaries – I was born during the Siege of Sarajevo, and I am surrounded by peers who have grown up as refugees. They grew up forced to comprehend home as a figuration and I’ve learned much from them. There’s an excellent book by young researcher Milica Trakilović on this topic, called Unraveling the Myth: Tracing the Limits of Europe through Its Border Figurations – what especially resonated with me is her individual experience of being taught Europe in geography class in the Netherlands in 1998: there was nothing on the map where Yugoslavia used to be.

My own mobility comes from privilege. Bosnia and Herzegovina is a peripheral, looted, and colonized space to the extent that its citizens equate joy, pleasure, and knowledge with privilege. In this sense, I have been extremely privileged my whole life. This privilege has been an obstacle in the social and cultural sphere of Bosnia, dominated by notions of violence and trauma. I felt ashamed of my joy many times back home. I am in the process of claiming this privilege.

I am not necessarily taking Bosnia and Herzegovina as my world. Its figurations have influenced my work, but I don’t feel like I belong there. At the same time, no one belongs there more than me. But it is annoying to have to claim your space in a space that is yours. Therefore, I am a feminist. At least that makes it fun.

It’s not easy for me to understand my current position, but I am starting to feel less powerless as I meet people who explore and accept these kinds of positionalities I outlined above. But I do know I view the world as a place where all forms of femininity must become more powerful – in all spheres of life. I don’t define power through patriarchal tropes; for me, to embrace our feminine power in the patriarchal world is to subvert reactionary expectations and identitarian categorizations, causing long-term effects in individual relationships.

9.png

Screenshot, Trailer for Quentin Tarantino’s film “Deathproof,” 2007

Aida: What does it mean to be an activist – media activist, artivist – in the everyday and interstitial spaces you operate in? Who is your audience? What is the collective and the community that inspires your work?

Hana: First, I’ll talk about the meme page, from where it all started some seven years ago. My audience is diverse. I have a social media following where women who are not feminist dominate. My output is perceived as feminist, although I really never fully claimed this position. I don’t have anything against it, but I wasn’t the one who said it first. It’s funny to me that I am perceived as the feminist in Bosnia – it’s kind of insulting to other feminists, really. I was the first one to create memes out of women’s experiences in the space of former Yugoslavia, and I am very happy that my legacy is this specific meme format which became a dominant way in which feminists of former Yugoslavia communicate. This format, you can’t really find elsewhere in the world, while women here recognized it and started using it.

Idioms inspire my work for the most part. It’s the little things I hear, which I perceive as notorious, nonchalantly oblivious to reality, ridiculous, and often idiotic, which end up as memes. They are a signal of deeply rooted masculine dominance in our communication and perception. They are often culturally specific, so only some are translatable and relatable in English. I tend not to react to current political affairs, I guess out of spite. Out of the same spite, maybe, I insist on colloquial language in academic work.

When it comes to my consulting and production platform which grew from Vještice (the witches), my aim is to collaborate with theorists and artists, and work towards subverting the autocolonial in public space. Here, I use “autocolonial” to represent something distinct from self-colonization. To my understanding and limited theoretical knowledge, the “self-colonizing” process in Eastern Europe has been inextricably linked to the internalization of Eurocentric values on the level of mind/consciousness. Perhaps I am wrong.

But I use “autocolonial” to reflect the multiplicity of “self-colonizing” processes in Bosnia which are not only Eurocentric, but work on a variety of levels. This might be a long shot, but for me “autocolonial” represents the subjugation of one’s own identity towards the desirable external gaze (Sarajevo’s gaze, Russia’s gaze, a political party’s gaze, NGOs’ gaze), always aligning it with corresponding ingroup affects.

For me, there is no epitomized difference between “auto” and “self;” I just wanted to differentiate the two concepts, although the latter one is quasi non-existent.

But the platform is also a project to make money. I would like this to become a lucrative social venture soon. I am not opposing such notions out of ideology.

Activism feels so vintage for me. I don’t even know what it is, coming from the Bosnia and Herzegovina of 2022. I don’t understand this concept of activism in a colonized state. I say this because it seems that the perception of activism in Bosnia and Herzegovina is directly linked to the colonial reality of the country. For example, an activist is someone who gets support to draw murals about reconciliation on a ruin of a university building that has not been renovated since it was shelled during the Siege. I don’t understand how this is activism, and I don’t see solidarity, knowledge, or criticism in such activities. Activism can’t be lonely, and this is what it feels like back home – that’s why I’m not eager to call myself an activist. On the other hand, I have a great deal of respect for older activists, who still pursue their struggles. But I don’t see their legacy being continued, except in a few particular cases in the education sector. I am not dismissive of activists of my own generation, but I am critical of the reality within which they successfully operate and which they further empower.

2_1.png

bell hooks at The New School (Photo: Spencer Kohn, 2013)

Aida: You collaborate with artists but also with social theorists. Please tell us more about these collaborative experiences and ways in which they traverse social and political boundaries in the former Yugoslavia.

Hana: The space I live in is the meta-Yugoslavian space, a term I adopted from the theorist Svetlana Slapšak. This space is on the other side of the mirror of what has become of our countries. I think members of this space recognize each other and are a community of melancholy, humor, and feist.

Aida: Humor is incredibly important for your social media activism. Could you say a few words about the political power of humor?

Hana: Humor comes amidst chaos! I think it’s the most powerful political tool because it plays directly with the human affect, in the same way prejudice does. If prejudice and categorizations are the right’s answer to chaos, we, the rest of us, people who succumb to truth in a post-truth world, have humor as our answer. I don’t think it has been utilized that well politically, though. Academia and politics are still too prudish.

Aida: What is the potential of social media platforms for political subversion? How do you interpret that subversive work?

Hana: I don’t think there is potential in social media platforms to awaken substantial political change rooted in truth. Social media are private entities that had a large impact on removing truth as a philosophical basis of reality. I am a big fan of truth and power – but at the moment they are coopted by hegemonic masculinity. What we can do with social media is create these archives of knowledge and share them with people who otherwise wouldn’t come across them.

When I was younger, my idea was to take the radical democracy principles of philosophers Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau and apply some of them practically in the social sphere of Bosnia and Herzegovina. I’ve seen positive effects of this to an extent. For example, I managed, through my memes, to utilize shaming of patriarchal notions and violence through humor while simultaneously educating on details from post-colonial, decolonial, and feminist theory. But this has resulted in my individuation, rather than a conversation.

After being educated a bit more, especially through the work of the philosopher Gal Kirn, I am now closer to believing that the potential for all of this content lies in understanding it as a counter-archive; however, as I said, I am a big fan of power in the sense that I believe in seizing the means towards an end – an end that is disruptive to the current context. In this regard, I am still trying to understand how disruptive counter-archives can actually be in deeply traumatized and looted social spheres such as the one of Bosnia and Herzegovina, what decolonial role they can play in societies such as German, Austrian, Hungarian, as well as if they should at all.

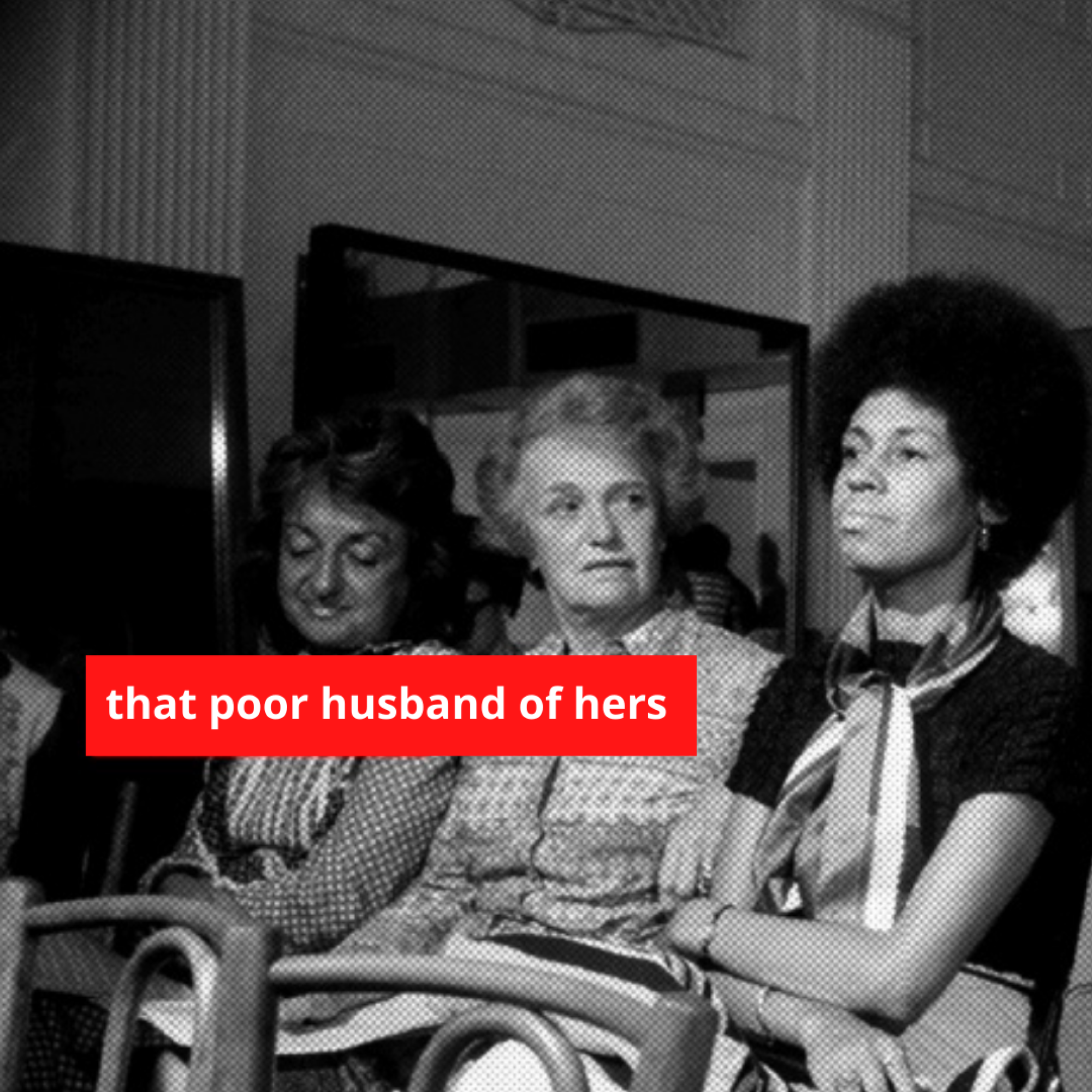

11.png

From left to right: Betty Friedan, Elinor Guggenheimer, and Eleanor Holmes Norton at an early meeting of the National Women’s Political Caucus. (Photo: Don Hogan Charles/The New York Times)

Aida: Why memes? (What are your favorite ones, could you interpret them for the readers, and could we use them as illustrations with the text)?

Hana: It was the thrill of the moment back in 2016. My guy friends were creating meme pages and I hated their memes because I realized how peripheral my existence was to them and how unfunny they were. So I made my own. It wasn’t a conscious decision; we were all starting to communicate through memes back then. Today, I love memes and the monsters they’ve become.

Aida: Some figures recur in your memes – Virginia Wolf, Simone de Beauvoir, Jovanka Broz. Some memes include “famous” women such as Melania Trump or Michelle Obama, women not known for either feminism or anti-colonialism or any kind of progressive global politics – and the memes bring them to earth from their celebrity or iconic pedestals. How do you select subjects of your memes? What do these women stand for and represent in your political world and the world you wish to intervene in?

Hana: Simone de Beauvoir was my first choice primarily because there are so many pictures of her and Sartre available online. She was also the only female philosopher mentioned in pre-college education in Bosnia and Herzegovina, so I hoped people would know her face (at least now they do). Afterward, I started building certain characters, mixing biographical elements of renowned Western public figures with people I knew from my own surroundings, or tropes that they were playing into. These are kind of caricatures of both the Westerners I use and the martyrs of patriarchy I find back home. Sometimes, it’s to give praise to theory and share my thrill of research with the audience, but sometimes it’s plain fuckery, if I might say so. Recently, I’ve also introduced images of cultural, religious, and public life in Bosnia and Herzegovina, on which I intervene with the goal of reclaiming the gaze (of the photographer and of my audience). I put them there because I realized that the large Serbian community which follows my meme page doesn’t know anything about Bosnia and Herzegovina or they are stuck in some crazy normalization of war – these kids were born during or after the wars of the 1990s.

Aida: The history of women’s activism and feminism in the former Yugoslavia is rich and complicated. What prompts you to keep excavating it?

Hana: Two things. First, the feeling that I am one of Yugoslavian women. Second, the gratefulness I feel towards them for facing injustice and violence I am, today, not exposed to.

I primarily relate this to women from my own family, who weren’t active in the public sphere, but whom I see as heroines.

5_1.png

Unable to locate original source. Image of Martin Heidegger.

Aida: I know that you have examined and considered the role of temporalities in the post-war, post-Dayton, post-socialist present. How do those temporalities intersect with activist interventions targeting a future?

Hana: It’s my colleague Dženeta Hodžić, an ethnographer and anthropologist, who suggested we tap into the topic of temporalities, because we were discussing a book that profoundly shaped us both – Stef Jansen’s Yearnings in the Meantime. It’s to her that I owe an introduction to this topic and am grateful for her selfless sharing of her knowledge with me.

How do those temporalities we identified intersect with activist interventions targeting a future? That’s a similar question I asked before in my MA thesis! I’ve identified the motivation of individual actors confined within Bosnia’s figurations but working in powerful institutions otherwise irrelevant to Bosnia to play a crucial role, at least in the cultural sector. I must explore this further, though, it’s still a weak argument.

Aida: There is a tension between feminist, post-structural, and post-colonial/de-colonial thought; between the presumed universalism of the former which erases (or does not even make possible) experiences of women from elsewhere and the struggles that they are engaged in. How do you see these tensions operating in the political landscapes of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the former Yugoslavia, the Balkans, Europe? How do they inform your work and your activism?

Hana: My friend Danijela Dugandžić gave me a gift when I was in my early twenties, it was a book by Dragana Tomašević called Sve bih zemlje za Saraj’vo dala (“I’d give up all the countries for Sarajevo”). It tapped into archives of scriptures written by women in and about Sarajevo from the Ottoman period up until today. This was a very important book in my feminist education because it introduced me to the multitude of feminisms that exist in this small space called Sarajevo. Can you imagine how many there are in the world, then!

One of the first lessons I learned back home was that the notion of women solidarity is vague and often artificial, because we live in a masculine world – in Sarajevo there was also this dimension of women trying to make a name for themselves in a ruthless, violent environment and thinking the town is too small for the both of us, which is always amusing, until it isn’t.

You can’t have solidarity with all women, but you should have solidarity with every person who consciously employs feminist curiosity. There are mistakes along the way, of course.

Aida: We are writing at the time of another European war and great power polarization. How does the war in Ukraine resonate in your world?

Hana: I don’t know. I feel powerless in this regard. I am not able to comment on it, and every time I do, I feel like I should wash my mouth. The only thing I can say is that I was hoping for a strong activist rallying in Bosnia and Herzegovina for Ukraine, but in the end, it wasn’t strong. I thought it had more potential than other rallying attempts because the cause and consequence were different and external, but on the other hand, I am aware of how closely we Bosnians live to death – so I understand why it wasn’t strong. I’m over the expressions of solidarity in Berlin, where it feels like any other rave. It’s depressing to see Nie Wieder Krieg written all over the place.

7.png

Original digital illustration by Hana Ćurak, inspired by the character of Simone de Beauvoir.

Aida: Is there anything politically productive that could be mined from the history of non-alignment for this moment of dread?

Hana: That is an excellent question! Through looking at the NAM archives, we can at least understand the postcolonial condition of its members and easily identify hegemonic and toxic masculinity as the mechanism of failure.

But there’s so much beauty to learn from it, as well – a good starting point for me was Naeem Mohaiemen’s film Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017), produced for documenta 14 in Kassel.

Aida: Who would you like to build solidarities with? Where do you see and find allies in these dark times?

Hana: I have been building solidarities with institutions in Berlin and academics in Germany and the US that work at the intersection of decolonial and feminist. I want to continue doing so. Also, many individual contemporary visual artists from the former Yugoslavian region. I would like to be able to get them all the money they need from the places that would otherwise not consider them, I’ve been doing a lot of copywriting and project writing in this area. I’m incredibly grateful to the anthropologist Čarna Brković, who was one of the first academics to fully dedicate her attention to my cause.

I would love to be able to work with institutions of culture in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but I don’t think I can be perceived as powerful now. Not because of me, because of them.

Aida: There is incredible talent and creativity in Sarajevo, even though politics has done everything to destroy them. What could those who believe themselves to live in the world’s metropoles take away from the city’s life and the resilience and humor of its residents?

Hana: How to get by with very little, how to cook without food, how to let go, how to be a poor European, how to have all your contemporary visual artists move to another country.

8.png

Original digital illustration by Hana Ćurak, inspired by the character of Simone de Beauvoir.

Bonfiglioli, Chiara. “Feminist Translations in a Socialist Context: The Case of Yugoslavia.” Gender & History, 30 (1), 2018, pp. 240-254.

Chandler, David. Bosnia: Faking Democracy After Dayton (London: Pluto Press, 2000).

Ćurak, Hana. “I am generation equality.” UN Women, February 1, 2021. Available at: https://eca.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2021/02/i-am-generation-equality-hana-curak-feminist-blogger-and-activist

Hadžiristić, Tea. “Is Bosnia the worst place to be a woman?” Open Democracy, December 5, 2016. Available at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/women-in-bosnia/

Hozić, Aida A. “Dayton, WPS and the entrenched ‘manliness’ of ethnic power-sharing peace agreements.” London School of Economics, Women, Peace and Security Blog, February 15, 2021. Available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/wps/2021/02/15/dayton-wps-and-the-entrenched-manliness-of-ethnic-power-sharing-peace-agreements/

Hozić, Aida A. “Making of the Unwanted Colonies: (Un)Imagining Desire” in Jodi Dean (ed.) Cultural Studies and Political Theory (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000), pp. 228-240.

Kurtović, Larisa. “When the ‘People’ Leave: On the Limits of Nationalist (Bio)Politics in Postwar Bosnia-Herzegovina.” Nationalities Papers, 49 (5), 2021, pp. 873-892. doi:10.1017/nps.2020.42

Tax, Meredith. “Five women that won’t be silenced.” The Nation, May 10, 1993. Available at: https://www.dubravkaugresic.com/writings/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Five-Women-That-Wont-Be-Silenced.pdf

Trakilović, Milica. Unraveling the Myth: Tracing the Limits of Europe Through its Border Figurations (Utrecht: Utrecht University Repository, October 16, 2020). Available at: https://dspace.library.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/1874/395198/UnravelingMyth_v13_Digital.pdf?sequence=4