“No Longer in A Future Heaven?” Women, Revolutionary Hope, and Decolonization

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Annual Convention of the International Studies Association in Las Vegas, USA, in March 2021 (virtually). I would like to thank the participants for their generous engagement with my paper, and I am especially thankful to Rahul Rao for his insightful, detailed and thought-provoking reading of the draft in his capacity of discussant. The paper was also presented at the virtual workshop organized in preparation for this special issue, which took place in February 2022. Again, many thanks to the participants for their fantastic comments and questions. I am grateful to Nicola Pratt for generously taking the time to read the paper and offer very helpful comments. I am indebted to the anonymous reviewer for their engaging reading of the revised draft and for offering incredibly helpful suggestions. Many thanks also to Ghiwa Sayegh at Kohl for her exceptional editorial support.

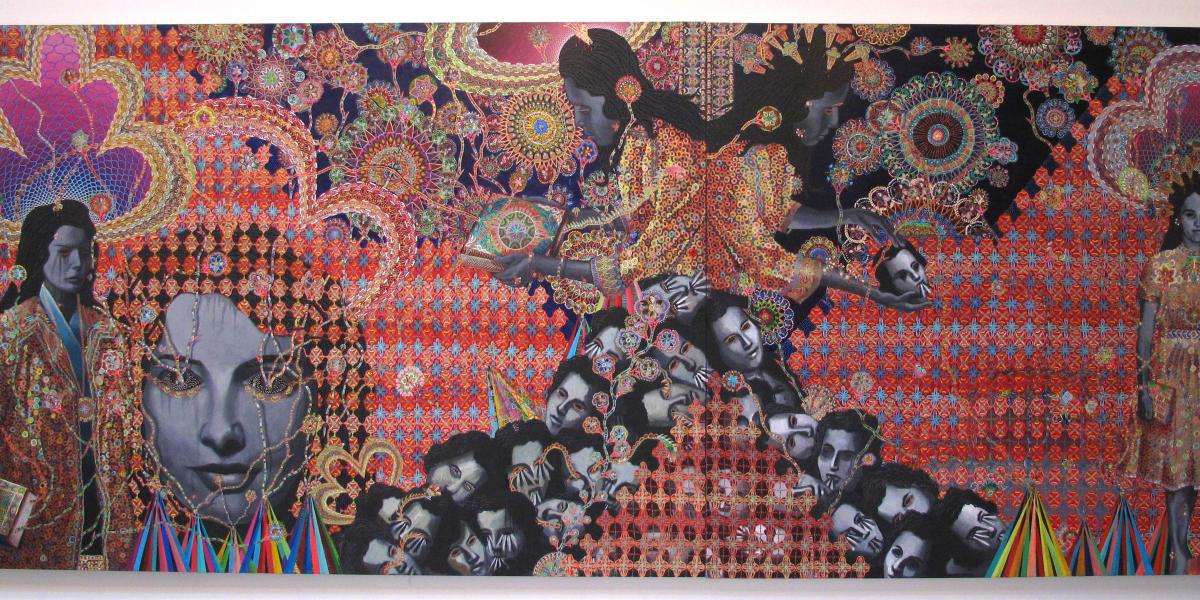

les_femmes_d_alger_20_60x144_2012.jpg

Les Femmes D'Alger, 2012

The wound is where light enters.

Rumi

They said that woman is half the nation, but

they only say that when they want to give woman the utmost

of her rights or to compliment her. I say that woman is all the nation;

without her this worldly heaven would not have existed.1

Mary Shihada

Our blood is the same as men’s. Our blood is not water. Our blood is blood.2

Djamila Bouhired

This essay is a reflection on the location of woman/women in decolonization struggles. It explores the tensions between gender/feminism and nationalism, or rather the complicated transactions between colonialism, patriarchy (both Western and local), national liberation, and the “woman question.” While many analyses regarding the role of women in the anticolonial context highlight either their lack of agency vis-a-vis the nationalist movement (the prevailing feminist view) or their political autonomy as historical agents (the postcolonial feminist perspective), this discussion aims to go beyond this binary. Beyond the image of woman as a historical force or woman as a victim of her historical context, lies the idea of woman as wound. The emphasis here is thus not so much on the “contributions” of women to decolonization processes, but on the idea of revolutionary hope as a deep wound that continues to haunt the memory of decolonization and its subsequent betrayals. In that vein, I explore women’s entanglements with decolonization in Algeria and Palestine. However, the emphasis here is not on the Palestinian women’s movement per se but rather on the manner in which they internalized the history of Algerian women’s trajectory in the project of national liberation.

The discussion draws its theoretical impetus from two overarching concepts, Hisham Sharabi’s neopatriarchy (1988) and Julietta Singh’s mastery (2018). Although writing at different times and towards different problematics, both authors attempt a diagnosis for the missed opportunities and betrayals of decolonization. Sharabi’s conceptualization zooms in on the Arab world, whereas Singh’s takes decolonization as a general even global framework for her analysis. Both go beyond a framework of domination of women by men, and posit a more encompassing diagnosis for the forms of postcolonial violence that have attended the national liberation state/project. Drawing on these two conceptualizations, the discussion delves therefore first into a theorization of the forms of domination that are associated with the national liberation state. It then examines in both historical and theoretical terms the “woman question” in a variety of settings in the Maghreb and the Mashreq. Of particular note here is an engagement with Frantz Fanon’s positioning vis-à-vis the woman question. Given the centrality of Fanon’s thought to and militant engagement with the anticolonial struggle, it is important re-visit and attend to the kind of wounds that Fanon’s work exposes. The essay ends with a reflection on the conversation between Audre Lorde and James Baldwin on revolutionary hope and the idea of woman as both wound and limit, and what these portend for radical futurities.

Kaleidoscopes of (anti)colonial domination: neopatriarchy and mastery

The neopatriarchal state,

regardless of its legal and political forms and structures,

is in many ways no more than a modernized version

of the traditional patriarchal sultanate.

Hisham Sharabi, Neopatriarchy, 7

… decolonization was an act of undoing colonial mastery by

producing new masterful subjects.

Julietta Singh, Unthinking Mastery, 2

Analyses examining the position of women in colonial/postcolonial settings have indicated the salience of processes of colonialism, imperialism, and nationalism/nation-building to understanding the many iterations of women’s movements and women’s rights discourses in the (post)colonial world. Women’s role both in decolonization struggles and in postcolonial nation-building projects was intimately entangled with forms of colonial domination, imperial norms for civilization and modernity,3 and the national liberation state’s projection of its own vision of liberation, modernity, progress, and development.4 And while studies have paid attention to patriarchy both in its colonial/imperial variants, and in its local instantiations, the general analytical approach has been to 1) understand patriarchy as primarily involving the domination of women by men, and 2) to deploy the concept of “patriarchy” without much substantive examination of its content, historical formations, and discursive and socio-economic characteristics.5 As Deniz Kandiyoti remarks, the concept of patriarchy is both overused and undertheorized in feminist literature.6 What is then remarkable about Hisham Sharabi’s study of neopatriarchy is that he devotes an entire book to studying in detail the historical formations, discourses, and the socio-cultural and political implications of what he identifies as neopatriarchy. His focus is the “Arab world,” namely the Maghreb and the Mashreq, and the central argument of the book is that the patriarchal structures of Arab societies, far from being modernized over the last century and a half, have in fact been solidified and legitimated by processes of colonialism and modernity.7 In effect, “neopatriarchal society was the outcome of modern Europe’s colonization of the patriarchal Arab world, of the marriage of imperialism and patriarchy.”8 Sharabi makes a pithy yet striking diagnosis, according to which “the neopatriarchal state, regardless of its legal and political forms and structures, is in many ways no more than a modernized version of the traditional patriarchal sultanate.”9

Sharabi devotes only a few pages to women’s position in the neopatriarchal state; and while this may be seen as a shortcoming of his analysis, the point is that he is less interested in a narrow deployment of “patriarchy” as domination of women by men than he is in exploring patriarchy as an overarching structure that conditions the many political, social, cultural, and economic processes in Arab societies. What he identifies as a central psychosocial feature of the neopatriarchal state is “the dominance of the Father (patriarch), the center around which the national as well as the natural family are organized.”10 European modernity and colonialism do not challenge this patriarchal dominance, but rather re-organize it in different forms. The neopatriarchal state has to constantly engage and re-position itself vis-à-vis its dominant other, the West, both as resistance and as fetish, as well as vis-à-vis its internal others (women, minorities, the poor, etc.). Even more forcefully, Georges Tarabichi speaks about the narcissistic wound experienced by Arabs in their encounters with the colonial European project. Tarabichi sees this wound as a form of pathology: “And what is the narcissist wound if not the condition of both becoming tributary and losing control over its course?”11 In contrast to Tarabichi’s Freudian/psychoanalytical lens, Veena Das, coming from a more socio-anthropological perspective (though also inflected by a Lacanian sensibility), envisions wound as a violation “inscribed on the female body […] and the discursive formations around these violations made visible the imagination of the nation as a masculine nation. What did this do to the subjectivity of women?”12 I argue here the two (the masculine wound inflicted by colonialism, and the female wound inflicted by local and colonial patriarchy) are intrinsically connected and disconnected: their connection is evident in the deployment of the trope “woman as nation” (which I explore in the next section), when the woman question becomes a linchpin in modernization projects and nationalist mobilization throughout the colonial world. Their disconnection also becomes palpable in the lag between the oversaturation of nationalist imaginary with the image of woman and the symbols of state-sanctioned femininity, and the absence and active marginalization of women’s voices, perspectives, stories, and presence from nationalist historiographies and from concrete national political and economic spaces.

Julietta Singh’s conceptualization of mastery highlights an in-built violence in national liberation projects. Singh’s study attempts a diagnosis similar to that of Sharabi of the failure of anticolonial movements to enact a more meaningful liberation of the national/social body. She states that “decolonization was an act of undoing colonial mastery by producing new masterful subjects.”13 More specifically, “in the anticolonial movement, mastery largely assumed a Hegelian form in which anticolonial actors were working through a desire or demand for recognition by another.”14 The problem with Singh’s deployment of “mastery” is that it does not tell the reader how exactly colonized subjects are re-configured as new masterful subjects. Whereas Sharabi’s analysis painstakingly fleshes out the historical contours and the types of processes involved in producing neopatriarchy as a material and thought structure, Singh’s discussion leaves a lot of questions unanswered: what exactly does Singh understand by mastery? How exactly are new masterful subjects produced? Is it simply desire for recognition by the colonial master, or is it more? What Singh’s analysis implies but leaves unexplored is perhaps the idea that in their desire to overcome and resist their colonial master, anticolonial movements ended up mirroring and emulating that which they resisted and opposed. I continue to rely on Singh’s idea of “mastery” because I do feel it has real analytical value and potential (albeit undertheorized). For the purpose of this essay, however, I will rely on Sharabi’s framework to flesh out some of the underdeveloped aspects of mastery.

The “woman question” and decolonization

To speak about the “woman question” in the context of colonialism and decolonization is to speak about the centrality of woman and womanhood/manhood to the wound inflicted by colonial trauma, to the impact of circuits of modernity and capitalism on colonial spaces, and to processes of emergent national consciousness and the anticolonial struggles that ensued. In her landmark study Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World, Kumari Jayawardena notes that under the impact of modernity and capitalist expansion, a reformist current emerged among the bourgeois and elite segments of local societies that embraced ideas of emancipation/modernization of women: “women needed to be adequately Westernized and educated in order to enhance the modern and ‘civilized’ image of their country and of themselves, and to be a good influence on the next generation; the demand grew for ‘civilized housewives’.”15 As Sharabi indicates, a paradoxical reality emerged where modern norms of gender emancipation and women’s education did not necessarily challenge local patriarchy but rather re-configured it into forms of “benevolent” patriarchy. The latter required (bourgeois middle and upper class) women to be educated and “civilized” while not daring to challenge the public/private divide (which happened to be maintained both by local and modern colonial patriarchy) or to unsettle let alone dismantle assumptions around what constituted respectable womanhood (educated, but not too educated, civilized and modern but not rebellious, well-spoken but not outspoken and defiant). What Lila Abu-Lughod calls “projects of remaking women”16 provided simultaneously both an opening and a closure for women by exhorting them to seek education and independence while also swiftly disciplining and punishing them if they stepped outside of the bounds of what was considered to be the appropriate amount of freedom.

This painful gap, this impossibility of reconciling desire and reality mirrors ironically (and symbolically) that of the national liberation state. In her assessment of the Nasserist project, Sara Salem notes precisely this predicament of having one’s imaginary horizons set around ideas of progress, prosperity, dignity, equity, and justice, while knowing that reaching them is unrealistic: “The predicament of anticolonial nationalism is not that these hopes were unrealistic or naïve; it is that a belief in independence meant that one had to have these hopes, while knowing how unlikely it was that they would ever materialize.”17 The structural weight of colonial modernity would constantly bear down on anticolonial aspirations and programs. If we are to take seriously Hisham Sharabi’s conceptualization of neopatriarchy as the “marriage of imperialism and patriarchy,” then we cannot disentangle the reality of colonial domination and re-structuring via capitalism and modernization processes from the emergence of the “woman question.” The “new woman” then was supposed to be the perfect blend of modernity and tradition: while (middle/upper class bourgeois) women were encouraged to seek education, it was for the purpose of becoming better wives and mothers, and thus better bearers of the new postcolonial nation.18 In effect, tradition would be summoned and re-deployed to blunt the edges of too modern and radical aspirations of independence, freedom, and autonomy by women in colonial societies. As Kumari Jayawardena remarks, “the new woman could not be a total negation of traditional culture,” since she was meant to be the “guardian of national culture.”19

In colonial settings such as Egypt, Palestine, and Iraq, “the ‘woman question’ […] became part of an ideological terrain upon which other concerns” – related to national culture, progress, and ability to “modernize” were articulated.20 Ellen Fleischmann notes that “[t]he main enemy of early reformers was ‘backwardness,’ rather than foreignness.”21 Women are thus tasked with the impossible mission of both upholding the honor of their families/nation and fulfilling the civilizing/modernizing aspirations of the local bourgeois reformers. Vijay Prashad notes that “the brief history of independence had shown these women’s rights activists that the national liberation state should not be left alone to be magnanimous in its gestures. The new states had not been nirvana for women.”22 The project of “state feminism” is the perfect illustration in policy of the purported (and paradoxical) ideal of the “new woman” as both a symbol of modernity and progress, and a repository of tradition. Chasing after ideals such as progress, development, and renaissance (nahda) meant that the state had to allow women access to the public sphere via employment and increased political participation while also moderating such openness with “gender-specific obligations that women (and men) were expected to meet.”23

What if the new woman refuses her role as “guardian of national culture” and caretaker of future generations? What if she wants to re-define her role? Can the national liberation project provide genuine admittance into its community to women? Hisham Sharabi, looking specifically at the Arab postcolonial state, and Julietta Singh, looking generally at the national liberation project, would both say no. Sharabi notes that as long as Arab postcolonial societies continue to organize themselves around the figure of the Father (the patriarch), groups and identities that threaten this overarching organizing principle will continue to be marginalized. As I mentioned earlier, Sharabi makes the argument that colonialism and capitalism not only did not challenge existing patriarchal structures, but simply re-configured and even strengthened them.24 Caught in a vicious cycle of simultaneous revulsion and attraction towards the West and its culture, Arab postcolonial societies developed a paradoxical engagement with the West: the desire to emulate the West’s modernity emerged alongside the counter-desire to promote and even re-invent a sense of “tradition.” To use Sharabi’s terms, this paradoxical relationship to the West seeks both to assuage the anxiety around perpetuating “the primordial patriarchal authority” (and thus keeping it intact),25 while at the same time attempting to meet the challenge of modernity by adopting some of its features and processes without posing a fundamental challenge to patriarchal authority.

For Singh, on the other hand, “anticolonial actors were working through a desire or demand for recognition by another.”26 On first impulse, I want to say that to see the anticolonial project as simply a Hegelian desire for recognition is simplistic and reductive. However, perhaps postcolonial scholars have under-estimated the hold this desire has had and continues to have. Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth seems to have been deeply aware of this trap of recognition27 – a careful reading exposes Fanon’s regular signaling throughout the book about the dangers of both the desire to replace the “master,” and of the imitation of European models and institutions:28 “The gaze that the colonized subject casts at the colonist’s sector is a look of lust, a look of envy. Dreams of possession. Every type of possession: of sitting at the colonist’s table and his sleeping in his bed, preferably with his wife. The colonized man is an envious man.”29 I suspect this envy and dreams of possession are the engine behind Singh’s conceptualization of anticolonial “practices of countermastery” though she does not explicitly engage these insights from Fanon. More to the point, Randolph Persaud remarks that the “tragedy of the [colonized] bourgeoisie ought to be read as the effects of colonial trauma.”30 Reading the tragedy of the national liberation state through the lenses of colonial trauma, Persaud continues, means that “local elite [can be seen] as sufferers, as much as perpetrators of harm to the nation.”31 This lens also complicates the story of decolonization as not only a heroic story of overcoming oppression, but also (simultaneously) a project of “strategic counterhegemony,” conceptualized by Persaud as “the drainage of colonial dreams, and the reconstruction of an internal rhythm, a rhythm where decolonization is a form of jouissance.”32 In that sense, decolonization should also be read as the project of “commanding modernity,”33 and here Julietta Singh’s conceptualization of anticolonial struggle as also a project of countermastery appears valuable.

Both Persaud’s (following Ilan Kapoor’s) understanding of decolonization as jouissance and Singh’s concept of countermastery allow us to expand on Sharabi’s argument that modernity and capitalism did not challenge local patriarchal structures but rather re-positioned them and even consolidated them. The “woman question” then emerges as the linchpin between the colonized man’s desire to master modernity, and his anxiety to maintain patriarchal authority unchallenged. Ellen Fleischmann, in her study of the Palestinian women’s movement, notes that “[m]any male reformers found the plight of women a powerful vehicle for the expression of their own restiveness with social conventions they found particularly stultifying and archaic.”34 Modernity thus provides an opening not only for women, but also for some of the men. However great the temptation of this opening is, the anxiety around it is just as great. This dilemma is illustrated in a scene in Latifa Al-Zayyat’s novel The Open Door (Al-bab al-maftuh),35 hailed as a classic of feminist anticolonial writing. Mahmud, the older brother of the main protagonist Layla, is an almost perfect prototype of this modern man stultified by traditions and rigid social norms: he openly rebels against parental authority, joins the anticolonial struggle, and mocks the norm of arranged marriage and the rigid expectations around women’s respectability. In a conversation with his cousin Isam, they argue about the right for women to choose their partners and marry for love. Isam openly disagrees with his liberal position and asks him to imagine what it would be like for Mahmud to find out that his sister Layla had fallen in love with a man. Mahmud’s spontaneous and violent reaction is highly telling and symbolic: “I’d kill [her], that’s what I’d do. I’d just kill [her].”36 The “woman question” becomes the wound of colonial modernity: she is seen as both the vehicle of progress (via education and emancipation) and thus a means to overcome “backwardness,” and an existential threat to entrenched patriarchal authority.

The politics of admittance: Algerian women and anticolonial violence

In an essay entitled “The Politics of Admittance,” cultural critic Rey Chow poses the following question: “how is community articulated in relation to race and sexuality? What kinds of admittance do these articulations entail, with what implications?”37 Pursuing a dual critical reading of Fanon’s articulation of women’s sexual agency via Freud’s articulation of community in Totem and Taboo, Chow notes that women are potentially dangerous to community because of their ability/potential to transgress the strictly set (racial, sexual, ethnic, religious) boundaries of community via physical contact (i.e. reproduction).38 Thus “female sexuality itself must be barred from entering a community except in the most non-transgressive, least contagious form.”39 In other words, “women are never erased but always given a specific corollary place: while not exactly admitted, neither are they exactly refused admission.”40 This tension becomes even more fragile and thus more visible when women are directly involved in violent national liberation projects such as in Algeria and Palestine. Decolonization becomes also the terrain where the narcissistic male wound intersects with the female wound: the revolutionary hope engendered by the fervent anticolonial mobilization and struggle (with all its emancipatory potential) produces a deep wound by betraying women’s expectations and socio-political horizons.

Both Marnia Lazreg, writing on Algerian women, and Ellen Fleischmann, writing on Palestinian women, have remarked that revolutionary violence provided an unprecedented opening for women to exert their political agency and thus “upset patterns of gender relations since at least the second half of the nineteenth century.”41 It also paradoxically had a chilling effect on women’s liberation as the pressing need of removing a violent colonial occupation required prioritizing the national struggle over women’s liberation. Fleischmann articulates an idea that has been at the core of countless anticolonial struggles, namely the “two-stage liberation theory:” national liberation would inevitably result in women’s liberation. This strategy would haunt generations of women’s activists throughout the postcolonial world.42 Women were asked to postpone their aspirations and demands for liberation until after the national liberation struggle would have been achieved, when a future heaven would await to honor women’s efforts and sacrifices.43

And yet, despite women’s immense contributions, as Lazreg herself notes in the case of Algeria, there is little recognition of their role in the anticolonial war.44 This is not an insignificant statement: numerous studies have been devoted to the history of the Algerian War, and yet the majority barely mention the role of women. The political agency of women is occasionally mentioned (i.e. a couple of pages may be devoted to it), and when it is, it refers overwhelmingly to the famous episode in the Battle of Algiers when a group of women were instrumental to planting bombs in the European quarter of Algiers (episode rendered memorably by Gillo Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers). The women were Djamila Bouhired, Zohra Drif, Samia Lakhdari, Baya Hocine, and Hassiba Bent Bouali.45 Nonetheless, the studies are entirely dominated by men as political actors with a rare occasional reference to women’s participation in the war. This sparse focus on women is also a reflection of the (Front de libération nationale) FLN’s attitude and policies towards women.46

Marnia Lazreg, in her book length study of Algerian women, entitled The Eloquence of Silence, states that women became “ideological pawns in the battle between the colonizers and the colonized.”47 The FLN adopted a generally condescending tone towards women, seeing them as “creatures of sacrifice.”48 The famous Soummam Platform, adopted at the FLN’s Soummam Conference in 1956, and considered to be the document that established the future independent Algeria, outlines the role of women as “providing moral support,” relaying intelligence, ensuring food supplies, looking after children and families, and providing shelter.49 As Lazreg herself remarks, these were the tasks seen as suitable for women’s abilities. El Moudjahid, the FLN’s mouthpiece, in a counter-critique to French colonial administration’s claims that Algerian women are oppressed by their men, claims that: “The Algerian woman does not need emancipation. She is already free because she takes part in the liberation of her country of which she is the soul, the heart, and the glory.”50 A far more ambivalent picture emerges from Mouloud Feraoun’s Journal, where the Algerian writer vividly captures both the backbreaking work (in its most literal sense) performed by women in the anticolonial war, and the socio-political constraints they faced:

…[w]omen are tending to the wounded, carrying them on their backs when there is an air-raid warning, burying the dead, collecting money, and standing guard. Since the rebels started mobilizing women, the [French] soldiers are beginning to arrest and torture them.

Perhaps a new world is being constructed out of ruins, where women will be wearing the pants, literally and figuratively, a world where what remains of the old traditions that adhere to the inviolability of women, both literally and figuratively, will be viewed as a nuisance and swept away.51

Feraoun’s vision for women’s liberation from both colonial and patriarchal shackles lies in an undefined future – his tone is fragile and tentative rather than declamatory with the whole statement hanging precariously on “perhaps.” This is not surprising given the steep hierarchy that organized political agency and subjectivity in the anticolonial struggle: as Lazreg (and others) remark, there were no women in the leadership of the FLN, and given that the FLN had become the only legitimate organization leading the anticolonial struggle, women had little political alternatives.52 Echoing Fleischmann’s statement mentioned earlier, Lazreg notes that Algerian women too were pinning their hopes on national liberation being the conduit towards a later liberation for women.53

Insofar as Algerian women are included in nationalist historiography, it is always as moudjahidates, heroic figures that validate the nationalist narrative without disrupting patriarchal authority. However, as psychologist and activist Doria Cherifati-Merabtine notes, although the women who joined the war were given the title of moudjahidates (fighters/combatants), a very small minority were actually fighters.54 The latter, for instance the porteuses de bombes in the Battle of Algiers, were called fidaiyates (guerilla fighters), and were overwhelmingly urban based. Indeed, Cherifa Bouatta argues that the Battle of Algiers “could not have taken place without these women.”55 As Djamila Amrane (a former fida’iya herself, and one of the porteuses de bombes in Algiers) notes, “the armed woman combatant was certainly not a reality, but rather a myth, perhaps based on a few individual cases which struck the popular imagination.”56 The myth of the moudjahidates provides sustenance to the FLN’s nationalist vision of a united Algerian nation, men and women, struggling against the French colonial rule. On the other hand, this never translated into acknowledging women as political agents and actors, nor were their voices included and recognized by nationalist historiography. The figure of the moudjahida becomes more than anything an icon of anticolonial resistance but within an overwhelmingly patriarchal nationalist story.

The fidaiyates, however, were brought into national and international spotlight. Djamila Boupacha’s story of torture and rape (and her subsequent trial) by the French colonial army became a cause célèbre for the French left with Simone de Beauvoir and Gisèle Halimi publicizing her story (which they later turned into a book). In 1962, Djamila Bouhired and Zohra Drif toured a number of Arab countries, among which Egypt where they were personally received and honored by Gamal Abdel Nasser, for the purpose of raising funds for an organization for the Algerian War orphans.57 Ironically, later in 1963, they both called for a press conference where they held both the Algerian and the other Arab governments accountable for not following through with their donation pledges.58 In 1963, Bouhired also visited China where she had tea with Chairman Mao.59 Nizar Qabbani wrote a poem for Bouhired, and the legendary Fairuz dedicated a song to her.60 An entire iconography was built in the Arab world (and beyond) around the figures of the fidaiyates/porteuses de bombes. Looking at the links between gendered images of the nation in interwar Egypt and the politics of women’s nationalists, Beth Baron muses on the paradox of having a nationalist historiography saturated with depictions of Egypt as woman while at the same time systematically excluding women from political participation in the nation-building project. She asks: “To what extent did women become ‘sites of memory’ themselves, symbols of an event or movement? Do women becomes symbols because they have already been excluded, or are they excluded because they are symbols?”61 In other words, what explains the stark disconnect between the hypervisibility of the fidaiyates in nationalist historiography and in the media, and the systematic betrayal and exclusion of women both during decolonization and after independence?62 Doria Cherifati-Merabtine speaks about the delegitimization and depreciation of the heroine trope in independent Algeria. The active and purposeful “negative appreciation of the modernist women’s movement” is meant as a conduit for addressing the anxieties triggered by the male narcissist wound, exacerbated – as Cherifati-Merabtine notes – by the rise of political Islam against the (perceived) secularism of Arab nationalist projects.63

I would like to go back to Rey Chow’s argument about the politics of admittance, mentioned earlier. Chow states that, on account of their potentially dangerous and transgressive capacity to community-formation, “women are never erased but always given a specific corollary place: while not exactly admitted, neither are they exactly refused admission.” She argues that the emphasis on “the regulation of kinship structures” is one way to displace the problem of female sexuality and thus to minimize its transgressive potential.64 This is evident in the obsession of both the colonial and the postcolonial state with the regulation of Personal Status Codes, a significant part of which revolves around issues pertaining to female sexuality and its corollaries (inheritance, marriage, divorce, child custody, etc.).65 In independent Algeria, the 1976 National Charter recognized the unconditional rights of women without discriminating between women moujdahidates and those who did not take part in the war.66 However, despite the fact that the Charter identified a number of social obstacles and ills that affected women, it did not suggest any structural solutions for them.67 Attempts were made throughout the 1970s to pass various drafts of a family code but without success. In 1981, a draft was formulated in secrecy but its approval was postponed until 1982 because of strong opposition to it from women’s groups.68 As Lazreg remarks, the draft “bore the hallmark of social conservatism” and unambiguously signaled to women that they lived in a society that legally empowered men to control women.69 1981 saw a series of demonstrations by women against the draft, led by the Women’s Collective of Algiers. Former revolutionaries such as Djamila Bouhired and Zohra Drif were among the leaders of these demonstrations. Not without irony, Marnia Lazreg states that “[t]heir appeals to the revolution, socialism and logic only underscored their powerlessness. […] they hung by the thread of the state’s moral obligation to some of them in their capacity as former fighters for an independent Algeria.”70 Appealing to their own contribution towards the building of the new nation and to their sacrifices in the Algerian struggle became the last resort available for their claims of inclusion into the new community. As Chow argues, they are neither fully admitted but neither are they excluded. Rather women are included on terms that are meant not to disrupt or challenge patriarchal authority.

I would like to turn here to Fanon’s portrayal of the role of Algerian women in the anticolonial struggle in “Algeria Unveiled” (1965). Feminist readings of Fanon’s famous chapter have indicated his complicity with FLN’s patriarchal narrative of women as “creatures of sacrifice.”71 In the chapter, Fanon positions the veiling and unveiling of the Algerian woman within a colonial context in which the overarching French colonial narrative aims to dominate the Algerian colonized (men) while purporting to liberate Algerian women from their local patriarchy. A notorious episode of this struggle between the colonized and the colonizer for authority to Algerian women’s subjectivity took place on May 16, 1958, in the midst of the violence of the Algerian War. The French generals who mounted a counter-insurgency both against the Algerian resistance and against the French government (by whom they considered themselves betrayed) organized a women’s demonstration, where they bused in women from nearby villages, with a number of women “solemnly unveiled by French women.”72 This public spectacle was supposed to illustrate the “liberation” of Muslim women.73 In “Algeria Unveiled,” Fanon comments on this episode and notes the backlash reaction that it triggered, namely that women started donning the haik again in defiance of the arrogance of the French colonial administration.74 Fanon notes that despite the fact that the reveiling might be seen as a “turning back,” a “regression,” the positive consequence of this episode is that the veil becomes politicized as tool for resistance, and not simply a boundary re-inforcing “tradition.”75 Marnia Lazreg complicates this reading and provides an elegant critique of both the colonial narrative and of Fanon’s engagement with it. She states that “[i]n reality the event of May 16, 1958 did lasting harm to Algerian women. […] Much has been said, and rightly so, about the generals’ manipulation of the veil as a political symbol separating the colonizers from the colonized, or its meaning as native men’s last bastion of resistance to the French, guaranteeing a safe haven of personal power in an otherwise dominated society. Little has been written about its meaning for women.”76

Indeed, a number of feminist critics have pointed to how Fanon’s focus on Algerian women rehearses in many ways the FLN’s narrative of women as sacrificial beings. The FLN’s El Moudjahid portrayed Algerian women either as “victims of colonial barbarity, or heroic embodiments of the new, armed Algerian woman.”77 Despite Fanon’s close attention to providing a context for the violent context in which the Algerian War unfolded, his portrayal of the Algerian woman seems somewhat frozen in time and lacking any depth: “an intermediary between obscure forces and the group,” she is of “primordial importance.”78 Fanon acknowledges that the Algerian woman becomes a linchpin between the colonial desire to dominate and control, and the colonized’s counter-desire to protect and resist. His focus is firmly on the former while refusing to contemplate the consequences on women of the latter:

After each success, the [colonial] authorities were strengthened in their conviction that the Algerian woman would support Western penetration into the native society. […] Algerian society with every abandoned veil seemed to express its willingness to attend the master’s school and to decide to change its habits under the occupier’s direction and patronage.79

As mentioned earlier in this article, the “woman question” becomes a wound of colonial modernity: her (un)veiled body is seen as the threshold between the colonial penetration of Algerian society, and the efforts of the colonized men to resist it. Framed in this stark light, an Algerian woman’s decision to unveil, for instance, can only be seen as an act of submission to colonial authority. Lazreg’s commentary, mentioned earlier, about the effects of the May 1958 demonstration on women raise a necessary question: where is women’s agency in this colonial contest?

Anne McClintock’s asks: “Where, for Fanon, does women’s agency begin?”80 Throughout “Algeria Unveiled,” the Algerian woman’s agency is framed (and stuck) in a rather simplistic temporality: until the revolutionary struggle, the Algerian woman was a symbol, a marker, and a keeper of the family and of tradition; it is only with the onset of the Algerian War that women are thrust into a new era of political action. There is no sense in which Algerian women have a history of political action, or of “prior […] consciousness of revolt.”81 “Until 1955, the combat was waged exclusively by the men,” notes Fanon.82 This is a critical element picked up by Marnia Lazreg’s analysis as well when she notes that “there is an unrecognized continuity in women’s participation in the political/military life of their country.”83 Not only were women active political/military agents resisting the French colonial conquest of the 19th century (captured, for instance, by Assia Djebar’s novel L’Amour, la fantasia, now a classic in North African literature), but even Islamic anticolonial discourses both in Algeria and beyond drew on stories from Islamic history of women heroes involved in political and military action.84

Anne McClintock is right in noting that in Fanon’s analysis, the Algerian woman’s political agency is never of her own initiation, rather hers is an “agency by designation.”85 As Fanon indicates, it was men who decided to allow women to participate in the war: “the decision to involve women as active elements of the Algerian revolution was not reached lightly.”86 But the women’s testimonies seem to tell a much more complicated story. Cherifa Bouatta (1994) interviewed a number of moudjahidates with a view to understanding women’s motivations and aims in joining the anticolonial war. She notes that her interviewees’ motivations are as complex as their individual situations: some saw the space of the anticolonial struggle as a space where they could escape from particularly oppressive family obligations and expectations, others joined the war via their links with close family members (especially common when direct family members had joined the FLN). Bouatta notes that the moudjahidates she interviewed reminisce the war as an exceptional moment in time when they as women felt respected and seen by their fellow comrades. Bouatta is of course careful to note there is a process of embellishing During-the-war memories precisely because of the disappointment and sense of betrayal that came for women After-the-war.87 The presence of former moudjahidates such as Djamila Bouhired and Louisette Ighilahriz at the forefront of contemporary protests, also known as the Hirak movement,88 is a powerful reminder of the enduring gap between the promised heaven of dignity and liberation for women, and a nationalist historiography that claims to honour the sacrifices of women but bars them from political participation.

“We would not be another Algeria.”

Algeria’s anticolonial war and its role in sponsoring and inspiring revolutionary movements throughout the African continent and beyond have earned it the title of “Mecca of Revolution.”89 On the other hand, the story of Algerian women’s involvement in the war and their subsequent betrayal by the national liberation state has become a cautionary tale for Palestinian women. The parallel between Algerian women’s story and that of Palestinian women stems from a certain similarity of historical context: both are situations of settler colonialism whose overwhelming violence gave rise in one case to an anticolonial war, and in the other to a movement of resistance against occupation that has lasted for several decades. In terms of women’s involvement, in both cases the urgency of resistance and liberation demanded of women to subordinate their claims of rights and emancipation to the overarching goal of national liberation. However, as several feminist scholars have noted, while historically the Palestinian women’s activism has indeed been circumscribed within the larger nationalist framework,90 the first Intifada (1987-1993) provided the opportunity for Palestinian women to shift their engagement from “nationalist activism to feminist-nationalism.”91 This shift can be explained by a broader base of its women’s movement, and by the success the latter has had in “introducing gender discourses into the national movement.”92 As outlined earlier in the introduction, the emphasis here is not on the Palestinian women’s movement per se but rather on the manner in which they internalized the history of Algerian women’s trajectory in the project of national liberation. Nahla Abdo notes that “[n]o going back” was a general motto adopted by Palestinian women during the first Intifada to refer both to the Algerian experience and to their own history of patriarchal domination.93 Abdo’s fieldwork interviewing women both in the West Bank and in the Gaza strip highlights a strong consciousness among Palestinian women of both experiences (the Algerian one and their own). Fatima, one of the interviewees from Beit Hanoun (Gaza strip), states: “What happened in Algiers will not be allowed to happen to us here… We have gone a long away. They should not be allowed to stop us.”94 The wound of revolutionary hope reverberates from Algiers to Palestine decades after the end of the Algerian War.

Concluding remarks: the wound of revolutionary hope and radical futurities

What happens to a dream deferred?

Langston Hughes

Julietta Singh’s argument about anticolonial movements producing practices of countermastery strikes me as accurate (though incomplete) when examining decolonization through a history of women’s struggles. Algeria became both the Mecca of revolutionaries and a warning tale for Palestinian women – these are not two different stories or divergent realities. Insofar as the goal of the anticolonial struggle was ousting colonial occupation and reclaiming a sense of autonomy and national dignity, the goal was accomplished (again, in a partial and incomplete manner). Hisham Sharabi’s claims regarding neopatriarchy as the organizing principle of Arab societies provides coherence to the dual story of Algeria as the Mecca of revolutionaries and as a cautionary tale for revolutionary women. The “two-stage liberation theory” (national liberation would inevitably result in women’s liberation, or, put differently, the goal of women’s liberation should be subordinated to the larger goal of national liberation) makes perfect sense within a neopatriarchal framework. It allows women to dream of a future heaven, possible even attainable yet forever deferred.

The wound of revolutionary hope contains also claims to a shared history of oppression and a shared history of struggle that obscure a much more complex reality of disjointed experiences of both oppression and struggle. The conversation between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde, published initially in Essence Magazine in 1984, is a stark reminder of the disjointedness of liberation. James Baldwin opens the conversation by assuming on Audre Lorde’s behalf a common belonging to the “American dream:” “Du Bois believed in the American dream. So did Martin. So did Malcolm. So do I. So do you. That’s why we’re sitting here.”95 Audre Lorde’s immediate reaction: “I don’t, honey. I’m sorry, I just can’t let that go past. Deep, deep, deep down I know that dream was never mine. And I wept and I cried and I fought and I stormed, but I just knew it. I was Black. I was female.” The entire conversation between the Baldwin and Lorde circles around this idea of disjointed experience of oppression, with Baldwin consistently attempting to explain the Black man’s anger (in general, but also towards Black women) in relation to the wider American system of dehumanization and oppression. Lorde, on the other hand, invites Baldwin to see the same system from her perspective of double oppression, to see and hear her story – and I’m not sure that he accepts the invitation. What struck me in this exchange is precisely his refusal to allow her story to simply be, with all its heart-breaking pain: “How can you be so sentimental as to blame the Black man for a situation which has nothing to do with him?” Lorde again summons him: “You still haven’t come past blame. I’m not interested in blame, I’m interested in changing…” More to the point, she states:

[…] we have to take a new look at the ways in which we fight our joint oppression because if we don’t, we’re gonna be blowing each other up. We have to begin to redefine the terms of what woman is, what man is, how we relate to each other.

JB: But that demands redefining the terms of the western world…

AL: And both of us have to do it; both of us have to do it…

What Audre Lorde articulates is the burden of mutual recognition and understanding both of the similarities of oppression but also (and especially) of the differences of it; and the burden lies on being open to seeing and accepting that one can be both oppressed and an oppressor. Perhaps what Lorde articulates is the beginning of breaking through the logic of mastery/countermastery via an invitation to re-define identities and ways of relating. It is both daunting and urgent.

- 1. Quoted in Fleischmann, 2003, 115.

- 2. Quoted in Harize, 2020.

- 3. Jayawardena, 2016; Ahmed, 1992; McClintock, 1995; Stoler, 2002.

- 4. Abu-Lughod 1998; Lazreg, 2019; Bier, 2011; Baron, 2005; Salem, 2017; Ali, 2018.

- 5. Deniz Kandiyoti expands on common understandings of patriarchy, but does not go as in depth as Hisham Sharabi (1992) does. See Kandiyoti, 1988; 1991.

- 6. Kandiyoti, 1988, 274.

- 7. Sharabi, 1992, 4.

- 8. Ibid., 21.

- 9. Ibid., 7.

- 10. Ibid.

- 11. Quoted in Kassab, 2010, 103.

- 12. Das, 2000, 205.

- 13. Singh, 2018, 2.

- 14. Ibid., 3.

- 15. Jayawardena, 2016, 8.

- 16. Abu-Lughod, 1998, 7.

- 17. Salem, 2020, 75. Original emphasis.

- 18. Jayawardena, 2016, 14-19; Kandiyoti, 1991.

- 19. Jayawardena, 2016, 14. See also Fleischmann, 2003, 9.

- 20. Fleischmann, 1999, 99. See also Ali, 2018, 53-61; Bier, 2011; Baron, 2005.

- 21. Fleischmann, 1999, 100. See also Ahmed, 1992, 162.

- 22. Prashad, 2007, 57. See also Armstrong, 2016.

- 23. Bier, 2011, 14. See also Hatem, 1992; Salem, 2017.

- 24. Sharabi, 1992, 7-8.

- 25. Ibid., 45. See also Kassab, 2010, 102-103.

- 26. Singh, 2018, 3.

- 27. Fanon, 2004.

- 28. See, for instance, Fanon’s conclusion, 2004, 235-239.

- 29. Ibid., 5.

- 30. Persaud, 2021. For more on colonial trauma, see Khanna, 2003.

- 31. Persaud, 2021.

- 32. Ibid. For decolonization as jouissance, see Kapoor, 2020.

- 33. Persaud, 2021.

- 34. Kandiyoti quoted in Fleischmann, 1999, 99. See also Fleischmann, 2003.

- 35. Latifa Al-Zayyat, The Open Door (Cairo: Hoopoe, 2017). Leylâ Erbil’s novel (2022) explores a similar problematique in the context of modern Turkey.

- 36. Al-Zayyat, 2017, 89.

- 37. Chow, 1999, 36. For a discussion of the politics of admittance in the context of the Dutch East Indies, see Sajed, 2017.

- 38. Chow, 1999, 39.

- 39. Ibid.

- 40. Ibid., 40.

- 41. Lazreg, 2019, 129.

- 42. Fleischmann, 2003, 138.

- 43. McClintock, 1995.

- 44. Lazreg, 2019.

- 45. Horne, 2006; McDougall, 2017.

- 46. Methodologically, it has been challenging researching on gender and decolonization in Algeria. As mentioned already, most studies of the Algerian War devote very little space to women’s voices or their challenges. I relied on English and French language sources, such as the works of Marnia Lazreg, Judith Surkis, and Natalya Vince but also on studies undertaken by Algerian researchers whose work has been published in edited volumes. The two researchers on whose work I draw here, Cherifa Bouatta and Doria Cherifati-Merabtine, are both social psychologists based at the University of Algiers. The former, for instance, conducted interviews with a number of moudjahidates with a view to understanding their motivation in joining the anticolonial struggle, their experience during the struggle, but also their experience of the new postcolonial nation of Algeria. There are a few instances where a number of former moudjahidates wrote their memoires: Djamila Amrane, Les Femmes Algériennes dans la Guerre (Paris: Plon, 1991), or even the more famous narrative of Djamila Boupacha’s story of torture during the Algerian War, written by Gisèle Halimi and Simone de Beauvoir, and entitled Djamila Boupacha (Paris: Gallimard, 1962). A more recent publication of a memoir by a moudjahida is Louisette Ighilahriz’ Algérienne (Paris: Fayard/Calmann-Lévy, 2001). Ighilahriz apparently dictated her life story to journalist Anne Nivat, and the book, published in 2001, immediately became a best-seller in France.

- 47. Lazreg, 2019, 131.

- 48. Ibid., 122.

- 49. Ibid.

- 50. Quoted in ibid.

- 51. Feraoun, 2000, 242. Original emphasis.

- 52. For an examination of the complex ideological terrain mapped out by the FLN in the Algerian War, see Sajed, 2019.

- 53. Lazreg, 2019, 131.

- 54. Cherifati-Merabtine, 1994, 41.

- 55. Bouatta, 1994, p.19.

- 56. Djamila Amrane, quoted in Cherifati-Merabtine, 1994, 47.

- 57. Vince, 2018, 222-223.

- 58. Ibid., 223.

- 59. Ibid.

- 60. Harize, 2020.

- 61. Baron, 2005, 3. Original emphasis.

- 62. This hypervisibility was temporary: only for the first decade after independence were the fidaiyates given attention, after which their names faded from public mentions.

- 63. Cherifati-Merabtine, 1994, 53-54.

- 64. Chow, 1999, 40.

- 65. For an examination of colonial law and gender in French Algeria, see Surkis, 2019.

- 66. Lazreg, 2019, 139.

- 67. Ibid.

- 68. Ibid., 143-144.

- 69. Ibid., 145.

- 70. Ibid., 146-147.

- 71. See, for instance, Sheshadri-Crooks, 2002; McClintock, 1995; Singh, 2018. For a defense of Fanon’s work against feminist critiques, see Gordon, 2015.

- 72. Lazreg, 2019, 127. See also McDougall, 2017, 220.

- 73. Ibid.

- 74. Fanon, 1965, 62.

- 75. Ibid., 63.

- 76. Lazreg, 2019, 127-128.

- 77. Vince, 2018, 225.

- 78. Fanon, 1965, 37.

- 79. Ibid.

- 80. McClintock, 1995, 365.

- 81. Ibid.

- 82. Fanon, 1965, 48.

- 83. Lazreg, 2019, 129.

- 84. See, for instance, Mernissi, 2012. This is a gorgeous study of female political and military agency in Muslim societies between the 7th and 11th century.

- 85. McClintock, 1995, 366.

- 86. Fanon, 1965, 48.

- 87. Bouatta, 1994, 32-33.

- 88. Bouattia, 2020.

- 89. See Byrne, 2016. The expression belongs to Amilcar Cabral: “The Muslims make the pilgrimage to Mecca, the Christians to the Vatican, and the national liberation movements to Algiers.”

- 90. See Fleischmann, 2003.

- 91. Gluck, 1995, 8. See also Abdo, 1994; Abdulhadi, 1992; Massad, 1995. See also Naila and the Uprising (film, directed by Julia Bacha, 2017).

- 92. Gluck, 1995, 10.

- 93. Abdo, 1994, 148.

- 94. Ibid., 166.

- 95. Baldwin and Lorde, 1984.

Abdo, Nahla. “Nationalism and Feminism: Palestinian Women and the Intifada – No Going Back?” In Valentine M. Moghadam (ed.), Gender and National Identity. Women and Politics in Muslim Societies. London: Zed Books, 1994.

Abdulhadi, Rabab. “The Feminist Behind the Spokeswoman – A Candid Talk with Hanan Ashrawi.” Ms., March/April, 1992, 14-17.

Abu-Lughod, Lila (ed). Remaking Women: Feminism and Modernity in the Middle East. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Ahmed, Leila. Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Al-Zayyat, Latifa. The Open Door. Cairo: Hoopoe, 2017.

Ali, Zahra. Women and Gender in Iraq: Between Nation-Building and Fragmentation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Armstrong, Elisabeth. “Before Bandung: The Anti-Imperialist Women’s Movement in Asia and the Women’s International Democratic Federation.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 41(2): 2016, 305-331.

Baldwin, James, and Audre Lorde. “Revolutionary Hope: A Conversation Between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde.” Essence Magazine, 1984.

Baron, Beth. Egypt as A Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005.

Bier, Laura. Revolutionary Womanhood: Feminisms, Modernity, and the State in Nasser’s Egypt. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Bouatta, Cherifa. “Feminine Militancy: Moudjahidates During and After the Algerian War.” In Valentine M. Moghadam (ed.), Gender and National Identity. Women and Politics in Muslim Societies. London: Zed Books, 1994.

Bouattia, Malia. “Algeria’s Women: Unsung Heroes of the Revolution.” Middle East Eye, March 8, 2020. https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/algerias-women-unsung-heroes-revolution

Byrne, Jeffrey. Mecca of Revolution: Algeria, Decolonization & the Third World Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Cherifati-Merabtine, Doria. “Algeria at a Crossroads: National Liberation, Islamization and Women.” In Valentine M. Moghadam (ed.), Gender and National Identity: Women and Politics in Muslim Societies. London: Zed Books, 1994.

Chow, Rey. “The Politics of Admittance: Female Sexual Agency, Miscegenation, and the Formation of Community in Frantz Fanon.” In Anthony C. Alessandrini (ed.), Frantz Fanon: Critical Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge, 1999.

Das, Veena. “The Act of Witnessing.” In Veena Das et al. (eds), Violence and Subjectivity. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000.

Erbil, Leylâ. A Strange Woman. Dallas: Deep Vellum, 2022.

Fanon, Frantz. “Algeria Unveiled.” A Dying Colonialism. New York: Grove Press, 1965.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Feraoun, Mouloud. Journal 1955-1962: Reflections on the French-Algerian War. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2000.

Fleischmann, Ellen L. The Nation and Its “New” Women: The Palestinian Women’s Movement 1920-1948. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003.

Fleischmann, Ellen L. “The Other ‘Awakening’: The Emergence of Women’s Movements in the Modern Middle East, 1900-1948.” In Margaret L. Meriwhether and Judith E. Tucker (eds), Social History of Women and Gender in the Modern Middle East. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1999.

Gluck, Sherna Berger. “Palestinian Women: Gender Politics and Nationalism.” Journal of Palestine Studies 24(3): 1995, 5-15.

Gordon, Lewis. What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and Thought I. New York: Fordham University Press, 2015.

Harize, Ouissal. “From Militants to Student Activists: The Women Who Fought for Algeria.” Middle East Eye, July 3, 2020. https://www.middleeasteye.net/discover/algeria-women-militants-independence-activists

Hatem, Mervat. “Economic and political liberation in Egypt and the demise of state feminism.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 24(2): 1992, 231–251.

Horne, Alistair. A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962. New York: New York Review Books, 2006.

Jayawardena, Kumari. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. London: Verso, 2016 [1986].

Kandiyoti, Deniz. “Bargaining with Patriarchy.” Gender & Society 2(3): 1988, 274-290

Kandiyoti, Deniz. “Identity and Its Discontents: Women and the Nation.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 20(3): 1991, 429-443.

Kapoor, Ilan. Confronting Desire: Psychoanalysis and International Development. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020.

Kassab, Elizabeth. Contemporary Arab Thought: Cultural Critique in Comparative Perspective. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

Khanna, Ranjana. Dark Continents: Psychoanalysis and Colonialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Lazreg, Marnia. The Eloquence of Silence. Algerian Women in Question, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2019.

Massad, Joseph. “Conceiving the Masculine: Gender and Palestinian Nationalism.” Middle East Journal 49(3): 1995, 467-483.

McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. London and New York: Routledge, 1995.

McDougall, James. A History of Algeria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Mernissi, Fatima. The Forgotten Queens of Islam. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Persaud, Randolph B. “Hegemony and the Postcolonial State.” International Politics Reviews 9: 2021, 70-79. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41312-021-00106-0

Prashad, Vijay. The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World. New York: The New Press, 2007.

Sajed, Alina. “How We Fight: Anti-colonial Imaginaries and the Question of National Liberation in the Algerian War.” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 21(5): 2019, 635-651.

Sajed, Alina. “Peripheral modernity and anti-colonial nationalism in Java: economies of race and gender in the constitution of the Indonesian national teleology.” Third World Quarterly, 38(2): 2017, 505-523.

Salem, Sara. Anticolonial Afterlives in Egypt: The Politics of Hegemony. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Salem, Sara. “Four Women of Egypt: Memory, Geopolitics, and the Egyptian Women’s Movement during the Nasser and Sadat Eras.” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy 32(3): 2017, 593-608.

Sharabi, Hisham. Neopatriarchy: A Theory of Distorted Change in Arab Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Sheshadri-Crooks, Kalpana. “‘I am a Master’: Terrorism, Masculinity, Political Violence in Frantz Fanon.” Parallax 8(2): 2002, 84-98.

Singh, Julietta. Unthinking Mastery: Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

Stoler, Ann Laura. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Surkis, Judith. Sex, Law, and Sovereignty in French Algeria 1830-1930. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Vince, Natalya. “Looking for ‘the Woman Question’ in Algeria and Tunisia: Ideas, Political Language, and Female Actors Before and After Independence.” In Jens Hanssen and Max Weiss (eds), Arabic Thought Against the Authoritarian Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.