Countering Colonial and Nationalist Histories: The Ethos of Libyan Poets Fatima ‘Uthman and Fatima Mahmoud

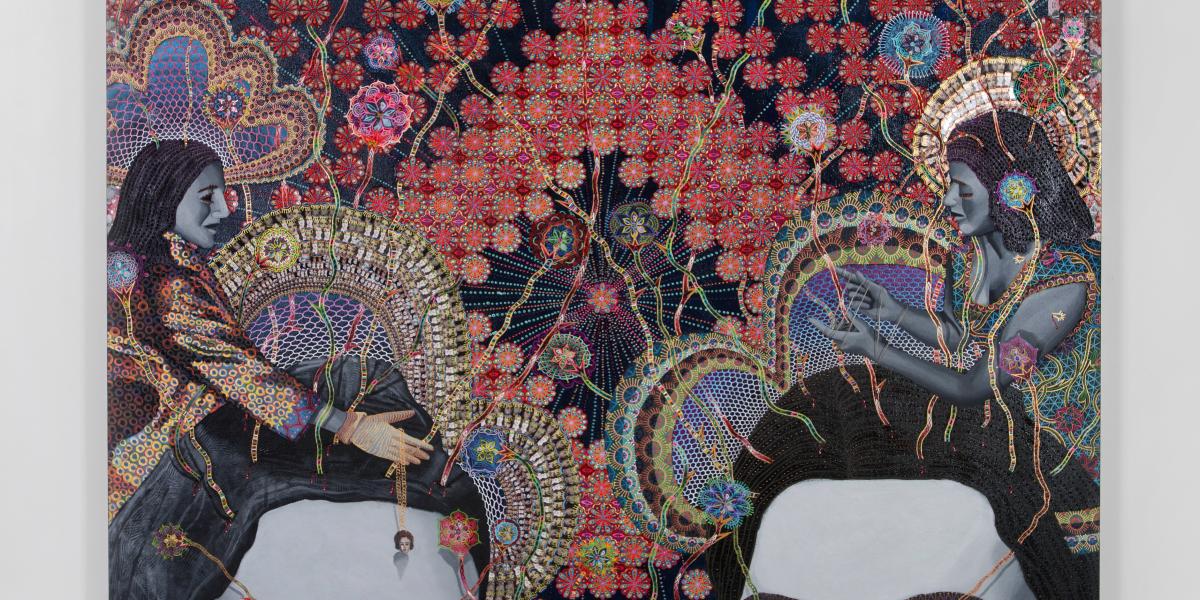

les_femmes_dalger_56_72_x_54_2016.jpg

Les Femmes D'Alger, 2012

Every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor

- Saidiya Hartman in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (2019:7).

Introduction

What is it to recount and (re)claim alternative histories and other worlds? Can we (re)examine our pasts and (re)imagine other worlds through anticolonial poetry?

Revolutionary anticolonial leaders have largely occupied our imagination as men who utilized all and any means necessary to liberate their people from colonial rule. Men like Umar Al-Mukhtar have captured the emancipatory imagination of many as heroic anticolonial figures, especially in Libya and the SWANA (Southwest Asia and North Africa) region. Al-Mukhtar and his efforts in leading the Libyan anticolonial resistance movement against the Italian Empire’s occupation of Libya has been memorialized extensively by the postcolonial Libyan state (Kawczynski 2011). Al-Mukhtar’s name, face, and heroic story is ever-living on Libyan dinar bills, street signs, school and hospital names, history classrooms, and households. Undoubtedly, Al-Mukhtar’s contributions to the Libyan revolutionary struggle and emancipation from the brutality of the fascist Italian Empire cannot be understated. However, the legends of Al-Mukhtar and other anticolonial heroes have served to portray a masculinist nationalist history and state identity that aim to serve the legitimacy of powerful men in positions of authoritative power. This prompts us to ask, what then are the stories of those who have been left behind and never made it to the history books of powerful men?

This paper seeks to examine how the site of the quotidian, both as theory and method, can be a tool for SWANA feminist interventions that disputes the narratives of power and authority and allows us to hear other stories and see alternate visions. I do so by engaging two interconnected questions: What is the significance of examining anticolonial/anti-authoritarian poetry, particularly those produced by women? Why should feminists look at poetry as a way of knowing otherwise? Through the lens of the quotidian,1 particularly the use of poetry and its presence in everyday life and expression in the SWANA, we can unravel narratives that have been undermined by the overarching power of colonial and authoritarian rule. Poetry has been an essential tool of communication and preservation of culture and history, and it is certainly rooted in Libyan oral traditions. Poetry “came to a new and powerful flowering, spurred on by the suffering and injustice visited upon the Libyan people by Italian colonialism” (Joris & Tengour 2012:365). As such, while masculine anticolonial hero narratives provide one lens from which we can examine the history of anticolonial struggle in the SWANA, quotidian Arab anticolonial/anti-authoritarian poetry offers a methodological and epistemic tool for SWANA feminists to access histories and visions created outside of the panoptical control of Empire and the postcolonial state.

The quotidian as a site from which we examine silenced histories is inspired by the works of postcolonial, Indigenous, and Black feminist thoughts which have attempted to rupture Eurocentric and masculinist chronologies of history rooted in the linear stories of major events from the perspectives of powerful (white) men. Rather, these feminists seek to unearth other stories that have been carefully concealed in the nooks and crannies of dominant historical accounts. I examine the widely known Libyan poem “خرابين,” or “Our Homeland Ruined Twice,” by genocide survivor Fatima ‘Uthman, and the poem “What Was Not Conceivable” by Fatima Mahmood, a political dissident of the Gaddafi regime. The two poems exemplify the ways in which quotidian Arab anticolonial/anti-authoritarian poetry, particularly those produced by women, can offer us a glimpse of other stories and visions that have been removed from the larger imaginings of colonial and state masculinist erasures and violences.2

I begin by providing a quick overview of Italy’s colonial history in Libya and how the concealment of Italy’s genocide through Fatima ‘Uthman’s poem, “Our Homeland Ruined Twice.” I then turn to Fatima Mahmood’s poem “What Was Not Conceivable” to explore the ways in which the Libyan state under Muammar Gaddafi reimposed colonial exclusions by concealing stories that did not fit into or threatened the state narrative. I conclude by examining how poetry as a quotidian site can also be a site of revolutionary imagining by analyzing the ways in which poetry manifests the destruction of colonial Empires and imagines revolt against oppression.

Tainted Colonial Archives and Other Stories of Genocide

Italy’s Fourth Shore

September in Libyan history is remembered by two significant events, the most notable and recent of which is Gaddafi’s takeover of the Senussi monarchy on September 1st, 1969 (Kumetat 2013). The other, less remembered but undoubtedly significant, is the Italian military’s forced invasion of Libya towards the end of September 1911 (Powell 2015). Though Libya gained independence from Italy in 1951, Italian colonial rule lasted until the 1960s with continued agrarian “demographic colonization” wherein Italian settlers continued to inhabit Libyan lands even after Italy’s official colonial administration ended (Ballinger 2016). The conquest of Libya was seen by the Italians as a significant feat and crucial to the conquest of East Africa (Ahmida 2020; Ben-Ghiat 2001). According to Ruth Ben-Ghiat (2001:125), “after Mussolini visited Libya in 1926, the country was targeted to become an overseas outpost of fascist modernity. Land reclamation schemes, tourist developments, and comprehensive urban planning schemes would realize the regime’s claim that Libya constituted ‘Italy’s fourth shore’.”

Italy’s modernity project greatly depended on the transformation of Libya into its “fourth shore” (Cannon 1977). The forceful invasion of Libya provided Italy with the opportunity to solve its “land-hunger” problem through a mass population transfer wherein working-class Italians would be given agricultural land in Libya to grow food and economically benefit (Ben-Ghiat 2001; Ballinger 2016). This grandiose scheme was brought on by a forceful imperial rule that led to genocide against the Libyan people for resisting the colonial administration’s plans. However, as I will highlight below, the history of the genocide has been concealed from historical accounts and replaced with a romanticized narrative of a lean and rehabilitative Italian colonial administration.

Romanticizing Colonialism in the Archives

What is known and how we know it is predicated on a meticulously crafted historical account. Feminist scholarships produced by Black, Indigenous and post/anticolonial feminists have pointed to the ways in which knowledge production since the Enlightenment era has glorified the perspective of the European male over all other worldviews and knowledges (e.g., Agathangelou 2011; Agathangelou & Killian 2016; Hill Collins 2000; Smith 2012; Simpson 2014). It is through the construction of a particular form of legitimized knowledge that inclusions and exclusions are created and thus hierarchal power and control are constituted and maintained (Lockman 2004; Mitchell 2002). According to Indigenous scholar Linda Smith (2012), the hegemonic history, produced by the dominant group and circulated by Empire, is presented to us as a totalizing, universal, and tamed discourse which supposedly brings together all known knowledges and shared human experiences in an orderly fashion.

It is in this Eurocentric hegemonic historical account that Empires of pasts and presents continue to access hegemonic power. Knowledge is power and power is contingent on knowledge being preserved and sustained through a particular lens and using specific tools. One tool used to maintain knowledge hegemony is the archives. While the archives have been utilized by critical scholars as a site from which we re-read history through different lenses and unearth alternate narratives, they do not allow us to uncover silences and absences and thus they bring forth other stories. The archives do not allow us to contest the written Eurocentric biases of the colonial gaze which deliberately sought to produce and contain hegemonic knowledge (Bastian 2002).

In examining the limitations of the archives, Ali Abdullatif Ahmida (2020) discusses how the silences around the Libyan genocide are rooted in the inaccessibility and the erasure of historical documents deemed to tell the story of colonial rule in Libya. Historians have noted that much of the historical archives kept by Italy have been deliberately destroyed to erase its tainted past in Libya (Ahmida 2020; Yeaw 2018). Furthermore, Ahmida notes that the archives, kept by the Italian state to fashion and maintain a particular narrative, deliberately sought to downplay the number of interned in concentration camps and minimized the number of dead. Additionally, and most shockingly, is the ways in which Italian historians, writers, and generals have constructed the genocide “as a positive effort in the modernization and settlement of the ‘savage’ nomads” (Ahmida 2020:26).

This according to Ruth Ben-Ghiat (2001:126) is the result of a strategic propaganda campaign that the Italian fascists designed and implemented to produce a particular narrative about their modernity project wherein the Italian army was depicted as “tireless altruists who built roads and bridges, transformed deserts into gardens, and brought peace and prosperity to the indigenous peoples.” These narratives have had a lasting effect in the ways in which Italy’s colonial rule has been “remembered” in dominant world narratives. As such, the significance of the archives is that they are seen in positivist-terms as being a homogenous and truthful historical account of what happened because of who produced them and where they are kept. These select spaces which are seen to hold the keys to history often shape and inform how history is remembered.

The Poet Speaks Back: Counter-Archives and Other Stories

Anticolonial poetry, like Fatima ‘Uthman’s, pushes back against the conciliatory and romanticized narratives of colonial history. ‘Uthman, who was born in the small Libyan town of Hun in 1920, created the poem “خرابين” (“Our Homeland Ruined Twice”) as a firsthand account of Italy’s ruthless genocidal rule over Libya. Throughout her poem ‘Uthman describes Italy’s colonial rule as “tyranny” (Ahmida 2020:179). In naming tyranny, she juxtaposes and shatters the orientalist colonial imaginaries of a civilizer who has come to save, help, and provide for a backward nomadic. Moreover, Uthman’s utterance that her home/land has been ruined twice can be interpreted in different ways, but most palpable is her underscoring the brutality of “progress” and “modernity” that the Italian colonizers attempted to bring to Libya, which as articulated above, counters the official narrative that the Italian state has tried hard to maintain.

‘Uthman states that “no work can be found,” “the lights are gone,” and “nothing remains” to speak to what has been taken and the desolate realities brought on by the so-called modernity project of progress (Ahmida 2020:179). ‘Uthman describes how “her tears continue to pour, lament the loss of the dear ones who are hanging from thin ropes” (ibid.). Hanging – whether “like the fruit of the date palm,” “from the gallows,” and where “those who did not flee were hung” – is a consistent theme of the poem (ibid.). It points to genocide as a tactical tool of the Italian colonizers who attempted to control the population of Libya and curb the locals’ continued resistance to the colonial modernity project of the Italian Empire.

The act of hanging that ‘Uthman mentions throughout her poem to symbolize genocide has been corroborated by the oral testimonies of the Libyan state archives and by recent scholarship. For instance, Jamila Said Sulayman stated in her oral testimony, “In the camp, it was rare that several hours would pass without a death” (Yeaw 2018:806). Recent research by the historical scholarly community has found that the pacification period in Libya from 1911-1943 was “one of the most violent in the history of the twentieth-century colonialism. This pacification was ruthless and led to the genocide of a large section of the native population” (Powell 2015:454). The population in Libya dramatically declined during Italy’s genocidal regime from 1.4 million in 1907 to 1.2 million in 1912, and by 1933, the population had declined to 825,000 (ibid.).

A second form of violence that ‘Uthman describes in her poem is the deliberate act of mass starvation by killing and confiscating livestock and removing people from their land (Atkinson 2012). She states, “Ruined twice, our homeland, no work to be found to take care of oneself” (Ahmida 2020:179) to describe the conditions of being unable to work off the land as most Libyans did at the time. According to Ahmida (83), “by 1933, 85% of the sheep and goats and 60% of the cattle and camels were destroyed.” This, according to the letters found in the Italian archives, was a deliberate fascist tool to destroy people and their animals, and to exterminate them by depriving them of their very means of subsistence and survival. Testimonies from the archives of the Libyan Studies Centre have also made countless mentions of their subsistence being wiped by the colonizers and the forceful use of starvation as an act of genocide. For instance, Sulayman states, “I remember my brother ‘Abd al-Rahman died of hunger and we shrouded him with a scrap of cloth and we buried him next to us in the sand…” (Yeaw 2018:806). Though recent scholarly research has gained access to the recorded testimonies and stories of those who witnessed the atrocities of the Italian genocide, the poetry of ‘Uthman provides an unshackled counter-narrative to that of the romanticized one of Italy’s colonial rule.

Against the Chronology of Time and Histories

According to Smith (2012) history is power and thus there is an urgency to reclaim it by those rendered outside of it is a repossession of power. Black and Indigenous feminist scholars have sought to rupture historical and chronological time by going back to look at the quotidian as a site from which we can gain access to the voiceless (e.g., Campt 2014; Hartman 2019; Hill Collins 2000; Simpson 2014; Smith 2012). Historical European panoptical time and the violence it imposes on how we remember and how we understand the world around us is rooted in the ways in which such time has been constructed in a linear chronology. Historical accounts have embodied this linearity wherein, according to Smith (2012:30), chronology becomes a method that allows “events to be located at a point in time.” Smith states that by looking at Indigenous history through European time and thus, colonization and exploitation, is to continue to privilege European panoptical time. She calls for us to revisit “a combination of the time before, colonized time, and the time before that, pre-colonized time” (24). In revisiting time differently, Smith points to a rupturing of history’s chronology that considers events to be “located at a point in time” (30) and everything before European time to be “prehistorical” and “belonging to the realm of myth and traditions” (31).

Revisiting time differently prompts us to think of alternate methods and epistemologies from which we can gain access to different worlds. Black feminist scholar Tina Campt looks at the politics of the everyday as a site from which we can reclaim voices, histories, and subjectivities of those rendered outside of colonial and state narratives and histories. Campt (2014) discusses the ways in which black feminist futurities can be conceptualized through the grammar of the “quiet” and “quotidian.” The quiet and quotidian are marked by the need to “look and listen for the future in other unlikely places, in the everyday practices of black communities present and past and come to find an alternative archive of the African diaspora.” Campt (2014) attempts to re-read history not through the established archives but through the passport photographs of black peoples from the Caribbean to symbolize the quotidian practice of refusal; she states:

[It’s] a refusal to stay in one’s proper pace, a striving for freedom, a possibility to live unbounded lives, as neither an act of simple interdiction nor bear transgression. It’s a refusal to be a subject to a law that refuses to recognize you, its defined not by opposition or necessarily resistance, but instead a refusal of the very premises that have historically negated the lived experiences of blackness as either pathological or exceptional to the logic of white supremacy.

In reclaiming the past by making visible those deemed outside of European masculinist historical time, Campt attempts to conceptualize black futurities within the politics of the everyday and the quotidian practices of quiet refusal.

While anticolonial and anti-authoritarian poetry is not always quiet and is often infused with rage, it provides us with a significant tool to chart untold stories and imagine other worlds. Through the poetic voice of those who lived and experienced the brutality of Empire and state repression we are told stories otherwise. These voices do not make it to the archives, history books, or libraries of former Empires and postcolonial states. Rather they are found ebbing and flowing through the mouths of neighbours, communities, and generations, without the silence markers of gender, race, and class. They speak against the dominant backdrop of masculinist and hegemonic chronological history making and history preserving. They allow us to reflect and recount otherwise and in doing so to re-examine our own presents and (re)imagine our futures. They push back against power in their accounts and in the salient and untamed method they use to recount. They are accessed in the everyday and speak of the everyday pressing down of Empire and authoritarianism.

Postcolonial State Narrative and the Silencing of Other Stories

Colonial Legacies and the Making of Authoritarian Masculinist State Narratives

Scholars have written extensively on the ways in which colonial legacies of control have made possible the conditions of (gendered) authoritarian regimes of the postcolonial state (Ayubi 1995; Bromley 1994; Mamdani 1996; Mitchell 1991; Pratt 2006, 2020; Schneider 2006). Khadija El Alaoui and Maura Pilotti (2019:710) note how postcolonial authoritarian elitist regimes adopted colonial legacies “that firmly establish social relations in power and control” by reimposing colonial hierarchies that rendered “their fellow men and women as children unprepared and unskilled to face the challenges of rebuilding collectives from ashes.” As a result, postcolonial state elites employed the tactics of surveillance and control of their colonizers. According to Nicola Pratt (2006:5), “the legacy of European domination created an impetus for the expansion of post-independence state institutions – including the police, the military, economic enterprises, and the bureaucracy.” This expansion and the constitution of the sovereign state through these institutions of surveillance and control sought to create the conditions necessary for the concentration of resources and state control into the hands of a singular all-powerful regime (Owen 2004; Pratt 2006).

The postcolonial state’s replication of the panoptical control of Empire expanded to the careful construction of the nation’s image using the tools of security and exclusion (Elsadda 2022; Khalidi 2017; Basu & De Jong 2016). Rashid Khalidi (2017) highlights how SWANA states’ “intense obsession with security” reimposes the colonial exclusivity of the archives and makes them difficult to access. The limited archives that Libya has are placed in the securitized and inaccessible Libyan Studies Centre. Muammar Gaddafi created the centre after taking power in 1969 to create a site of knowledge from within Libyan borders. The centre has some, but limited, textual and photographic evidence of the genocide as well as a collection of alternative archival methods such as oral testimonies by survivors from 1970-2006 (Ahmida 2020; Yeaw 2018). While the Libyan state may have made attempts to construct its own archives and produce its own knowledges and counter-narratives from within via the testimony of survivors, it did so to create a narrative that glamourizes masculinized heroes of Libyan history.

The postcolonial state of Libya reconstitutes the archives “as tools of the powerful, that seek to normalize, standardize and impose order” (Elsadda 2022:1). The long silencing of other narratives and ways of telling stories is rooted in the violent erasures that started during the colonial era and was extended by the postcolonial authoritarian state. Of the 1,500 oral narratives securely stored in the Libyan Studies Centre’s archives, “only a small percentage of them were conducted with women” (Anderson 1980; Yeaw 2018:793). This, according to Yeaw, is largely due to masculinist constructs of the Libyan nation-state; she notes that “this new narrative valorizes the resistance of the largely male mujahidin and championed the figure of ‘Umar al-Mukhtar…” (2018:793). Yeaw goes on to state “the male revolutionary was thus placed at the centre of the construction of a national Libyan history. This version of Libyan history was sanctioned by the authoritarian nature of the new regime that sought to monopolise the official narratives of Libyan history” (ibid.). As such, Gaddafi monopolized and perpetuated the masculine-anticolonial hero nationalist narrative to legitimize his authority by depicting himself as the new age messiah of masculine anti-Western national heroism. This, ultimately meant that those who did not subscribe to this narrative and Gaddafi’s politics would be contained, excluded, and eliminated (Emadi 2012).

Postcolonial Exclusions of Poetic Voices

Poetry and other literary works have been subjected to state control and surveillance under the Gaddafi regime, wherein they were “confined to small intellectual and artistic circles, due to the lead weight of repression that Muammar Qaddafi’s authoritarian regime extended over cultural and political matters” (Joris & Tengour 2012:365). During the 40 years of the regime, there was only one government-run publishing house which solely printed literature that was in support of the government’s nationalist agenda (Joris & Tengour 2012). Thus, these anticolonial-turned-authoritarian sites of knowledge are not enough to provide us with the tools to (re)examine the past and the visions held by those outside of these narratives.

When we look to poetry produced outside of and against the carefully curated history of colonialism and the state, one of the works we can find is that of Fatima Mahmoud. Mahmoud was a journalist in Libya during the early decades of Gaddafi’s reign (1967-1987) after which she migrated to Cyprus. There, “she started and became the chief editor of a magazine called Modern Sheherzade” which focused on Arab women’s issues (Joris & Tengour 2012:382). Her poem, “What Was Not Conceivable,”3 when interpreted through an anticolonial and anti-authoritarian lens, tells us of the patrolman who “sucks out the blood of language, strips the alphabet of its dots and tears out the plumes of speech” (379). Here, Mahmoud speaks of the ways in which the authoritative power of the patrolman has suffocated the means against which to speak and resist. In her own lived experience, Mahmoud was politically exiled for speaking against what she called Gaddafi’s “dictatorial political regime,” particularly the lack of free speech (382). She sought political asylum in Germany in 1995 to escape prosecution by Gaddafi’s regime and she continues to reside there.

In Mahmoud’s poetry, the patrolman is a figure of power who controls by silencing voices and life itself. Unlike ‘Uthman, who spoke from the context of her lived-experience of genocidal colonial regimes, Mahmoud embodies the lived-experience of a colonized people and of a people who have sought the freedom of a postcolonial life only to be met with the master’s tools in a different form. Mahmoud speaks of diminished dreams of freedom when she describes what was imagined. She states, “In harmony we entered the climate of water, in harmony with the law of the trees. In harmony we pronounced grass, recited hedges. In harmony – a horizon of carnations. A blunder of lavender.” She juxtaposes this with the patrolman’s doings wherein “he muffles the coronets of the flowers, buries alive the jasmine leaning out of the gardens of the gaze” (379). At first, Mahmoud is describing the hope that a liberated Libya brought, one of harmony, of a renewed self, of freedom to grow and imagine outside the control of Empire. This short-lived dream is one that is buried by the control of the patrolman who swaddles these dreams and the voices that speak of them. She describes the hopelessness of an ever-engulfing state of control by stating “we adjust our watches to the patrolman’s pulse rate. Our country, two embers away was an oven” (380).

The poetry of Mahmoud counters the official state narratives of the archives, bookstores, and libraries that depict Gaddafi as an anticolonial, revolutionary leader who upholds freedom of speech and yearns for the liberation of all colonized peoples (Suh 2019). Her story tells us of an alternate collective and harmonious vision, one that sought to grow flowers from the shackles of Empire, a homeland ruined thrice. This homeland and the vision for it have been undermined by postcolonial states’ authoritarian regimes. The quotidian anticolonial and anti-authoritarian poetry of Libyan women’s lived experiences tells us what the colonial and state narratives have deliberately kept out of the pages of history: revolutionary imaginaries of revolution and freedom against the backdrop of despair.

Conclusion: The Quotidian as a Site of Revolutionary Imaginaries

In Erica Mena’s (2009:112) analysis of Mahmoud Darwish’s revolutionary poetry, she states that anticolonial poetry is “context-generative” and thus “produce[s] ruptures leading to new possibilities.” When we examine the quotidian of anticolonial/anti-authoritarian poetry as a methodological tool that ruptures and presents possibilities, we are not merely unearthing marginal accounts and stories but also visions and imaginings of other worlds. Despite the hopelessness and despair that surrounds her, ‘Uthman is able to draw on divine hope and calls on an end to the colonizer and their rule. In her desolation, she calls for the demise of colonial subjugation by stating, “Come on a hot, terrible day, send a menacing, raging sandstorm, bring waves of bullets like rain, to knock down the infidels’ heads, send them to oblivion, that would bring me life and solace” (Ahmida 2020:180).

Similarly, Mahmoud, in her poem, describes the land as getting tighter, and carnations spilling and fleeing until they “draw us in blood spilled on the patrolman’s uniform, he rolls us into clusters in the imagination’s vineyard. Blood is our secret ink, blood our aged fire” (Joris & Tengour 2012:382). The latter part, which ends the poem, describes the blood splattered on the patrolman’s uniform as that of the revolution – the peoples’ secret ink. It is an ink which the patrolman has not been able to “strip” and “suck the blood out of” (379). Blood has withstood the tyranny and oppression of authoritarian rule, surviving the enclosing embers of a suffocated country and speaking back to power. Even if blood is the only thing left, it still bestows the hope of refusal, revolution, and freedom.

These other worlds of revolution and freedom that are envisioned by ‘Uthman and Mahmoud are a form of resistance that El Alaoui and Pilotti (2019:713) call “poetics with a knife,” wherein “the poet is able to fight back and resist the all-consuming power of Empire through their words which are distant from the somber and hopeless reality they were facing.” Moreover, Anna Agathangelou and Kyle Killian (2006:463) argue that anticolonial/anti-authoritarian poetry questions what has been made universal and true, such as the constructs and legitimacy of sovereignty and the violence of borders/nation-states by “taking to task the masculine power that constitutes particular divisions that people are forced to love.

As such, the quotidian of Arab anticolonial/anti-authoritarian poetry is a site from which SWANA feminists can go to examine the forgotten stories and visions of women and those left out of dominant historical accounts. The quotidian is not signified by big events, romanticized narratives and/or the swords of anticolonial masculine heroes. Rather, it is ever-present in the practices and rituals of the everyday, without borders or censorship of Empire and state. It is a site of refusal and a site of hope. It speaks back to domineering power. It demands other stories are told in other ways. It gives us glimpses of other worlds, of revolutionary imaginings, and allows us too to imagine otherwise.

- 1. I use the term quotidian to express the everyday practice of poetry as part of Arab cultural and linguistic tradition of expression. This usage is inspired by Tina Campt’s 2014 talk “Black Feminist Futures and the Practice of Fugitivity” and her 2017 work titled Listening to Images.

- 2. Libyan anticolonial and political poets are many and some are well known even outside of the Libyan state like Rajab Buhwaish, Ibrahim al-Koni, and Mohammad al-Fituri. However, I have chosen to examine these two poets to demonstrate the double exclusions of women’s narratives due to their gender and the means by which they contest and refuse.

- 3. Fatima Mahmoud’s poem “What Was Not Conceivable” has been translated by the Libyan poet-and literary writer Khaled Mattawa.

Agathangelou, A. M. (2011). Making Anew an Arab Regional Order? On Poetry, Sex and Revolution. Globalization, 8(5), 581–594.

Agathangelou, A.M., & Killian, K.D. (2006). Epistemologies of Peace: Poetics, Globalization and the Social Justice Movement. Globalizations, 3(4), 459–483.

---. (2016). Time, Temporality and the Violence in International Relations. (1st ed.) New York: Routledge.

Ahmida, A. A. (2020). Genocide in Libya: Shar, a Hidden Colonial History (1st ed.). New York: Routledge.

Anderson, L. S. (1980). Research Facilities in the Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahuriyyah. Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, 14(1), 27–31.

Atkinson, D. (2012). Encountering Bare Life in Italian Libya and Colonial Amnesia in Agamben. Agamben and Colonialism. (Edited by Marcelo Svirsky and Simone Bignall). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 155–177.

Ayubi, N. N. M. (2009 [1995]). Over-Stating the Arab State: Politics and Society in the Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris.

Ballinger, P. (2016). Colonial Twilight: Italian Settlers and the Long Decolonization of Libya. Journal of Contemporary History, 51(4), 813–838.

Bastian, J. A. (2002). Taking Custody, Giving Access: A Postcustodial Role for a New Century. Archivaria, 53, 76–93. https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/12838/14058

Basu, P., & De Jong, F. (2016). Utopian Archives, Decolonial Affordances: Introduction to Special Issue. Social Anthropology, 24(1), 5–19.

Ben-Ghiat, R. (2001). Fascist Modernities: Italy, 1922-1945. (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bromley, S. (1994). Rethinking Middle East Politics. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Campt, T. (2014). Black Feminist Futures and the Practice of Fugitivity. New York: Barnard Center for Research on Women. https://bcrw.barnard.edu/videos/tina-campt-black-feminist-futures-and-the-practice-of-fugitivity/

---. (2017). Listening to Images. London and Durham: Duke University Press.

Cannon, B. D. (1977). Review of Fourth Shore: The Italian Colonization of Libya [Review of Review of Fourth Shore: The Italian Colonization of Libya, by C. G. Segrè]. ASA Review of Books, 3, 39–44.

El Alaoui, K., & Pilotti, M. (2019). Walking with Lips Raining Fire and Love! Arab Poets’ Testimony to the World. Interventions, 21(5), 708–726.

Elsadda, H. (2022). An Archive of Hope: Translating Memories of Revolution. The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Memory. Edited by Sharon Deane-Cox and Anneleen Spiessens. New York: Routledge.

Emadi, H. (2012). Libya: The Road to Regime Change. Global Dialogue, 14(2), 128-142.

Hartman S. V. (2019). Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Hill Collins, P. (2000). Toward an Afrocentric Feminist Epistemology. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment. London and New York: Routledge.

Joris, P., & Tengour, H. (2012). Poems for the Millennium: Book of North African Literature. (Vol. 4). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kawczynski, D. (2011). Seeking Gaddafi: Libya, the West and the Arab Spring. London: Biteback Publishing.

Khalidi, R. (2017). The Humanities in the Arab World Today. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 37(1), 132–133.

Kumetat, D. (2012). Gaddafi’s Southern Legacy: Ideology and Power Politics in Africa. The Rise of the Global South: Philosophical, Geopolitical and Economic Trends of the 21st Century. (Edited by Justin Dargin). Singapore: World Scientific, 125–152.

Lockman Z. (2004). Contending Visions of the Middle East: The History and Politics of Orientalism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mena, E. (2009). The Geography of Poetry: Mahmoud Darwish and Postnational Identity. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 7(5), 111–118.

Mitchell, T. (1991). Colonising Egypt (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

---. (2002). The Middle East in the Past and Present of Social Science. In The Politics of Knowledge: Area Studies and the Disciplines (Vol. 3). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1–32.

Owen, R. (2004). State, Power and Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Powell, I. T. (2015). Managing Colonial Recollections. Interventions, 17(3), 452–467.

Pratt, N. (2006). Democracy and Authoritarianism in the Arab World. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

---. (2020). Embodying Geopolitics: Generations of Women’s Activism in Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schneider, L. (2006). Colonial Legacies and Postcolonial Authoritarianism in Tanzania: Connects and Disconnects. African Studies Review, 49(1), 93–118.

Simpson, A. (2014). Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. London and Durham: Duke University Press.

Smith, L. (2012). Imperialism, History, Writing and Theory. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London & New York: Zed Books.

Suh, S. C. (2019). The Pan-African Ideal Under a New Lens: The Contributions of Thabo Mbeki of South Africa and Muammar Gaddafi of Libya 1994-2008 (Doctoral dissertation). Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg.

Yeaw, K. (2018). Gender, Violence and Resistance under Italian Rule in Cyrenaica, 1923–1934. The Journal of North African Studies, 23(5), 791–810.