Queer Worldmaking and the Art of Selfies: A Photoessay

Thanks and gratitude to all those who contributed to this project in its different phases.

queer_selfies_9

A hand is holding a phone-like object, reflecting the part of the subject’s face on its screen. The hand looks artificial, as in that of an android.

The word selfie made its first appearance on the internet in 2003. However, the phenomenon goes much further back in history. The first selfie was reportedly captured on a daguerreotype camera in 1839 in Philadelphia by an amateur photography enthusiast. The turn towards the self for exploring different themes is as old as art itself.

The vast proliferation of selfies in our modern world could signal the influence of technology over our lives. Selfies are oftentimes dismissed as overt narcissism, or are linked to our neoliberal upsurge in today’s consumer society. In my view, selfies have aesthetic significance plus a generative potential that merits otherwise. As the cultural theorist Mette Sandbye holds,1 selfies are a form of productive, affective, and aesthetic labor as well as performative worldmaking.

What worlds are built and unbuilt when we use cameras and other imaging technologies to take selfies? This photoessay highlights the art of selfies, exploring themes like the body, futurity, displacement, exile, and visibility politics, revealing how queers shift and modulate realities, and what happens when imagination runs free.

queer_selfies_1

Left: The subject’s upper body and head are basking in the sun, blue sky behind her, staring into the horizon. She is on the cover of Vogue magazine. Photo courtesy of artist Lux Venérea

Right: The Subject lies on beach rocks, the sea and sky are visible behind them. She is on the cover of Vogue magazine. Photo courtesy of artist Lux Venérea

queer_selfies_2

Left: The subject is looking towards the camera, wearing a paige dress, a green scarf, and white-framed sunglasses. They are indoors and are holding a black purse, while leaning on the kitchen’s working table. Photo courtesy of Ragil Huda

Right: The subject is lying on a table in a sultry pose, staring towards the camera. A large, white purse is placed in front of them, covering their torso. Photo courtesy of Ragil Huda

“all i wanna do is *gunshot* *gunshot* *gunshot* and *cash register noise* and take your money”

- MIA, Paper Planes, 2007

When the artist and singer MIA, who grew up in the “refugee ghettos” of London, released this song, the provocative lyrics triggered both censure and censorship. For her, it was an expression of her frustrations with the (U.S.) demeaning visa hurdles, and a mockery of the perception of migrants and refugees, allegedly conspiring to exploit welfare systems and steal jobs from first-world citizens at the same time. Meanwhile, the song was hailed as “a torch song for the world's disaffected and poor.” I imagine Paper Planes playing as soundtrack for queer life.

The word queer is destined for contestation. When I say queer, I want to focus on exluded and marginalized narratives of queerness that challenge and threaten dominant voices. Queer and trans bodies who didn't benefit from cultural and economic capital passed on by their ancestors, or who don’t even know their ancestors. Third-world queers who are not part of privileged institutions, while their lived experiences hold wisdoms unattainable through academic training. Those whose daily marches don’t count as queer history, because they’re excluded from elite establishment historicizations. Those whose oppressions stretch the limits of identitarian demarcations. In other words, I want to keep it queer.

In the selfies above, it is not only an aspiration for a world where -phobias and -isms don’t exist, or where the borders are erased, that is expressed. We also get a glimpse of what reparations and justice may look like. Alternative queer worlds are built through the appropriation of tropes of success and mockery – how “making it” looks like.

queer_selfies_3

Left: The subject is dressed in an astronaut suit, while situated on an unknown celestial object. Planet earth can be seen in the background, while a car is seen flying in space. Photo courtesy of artist Demetrios Navras

Right: The subject is in alien form, her skin greenish, and her eyes and lips accentuated with what seems like makeup. Photo courtesy of artist Dalia Shash

Our lives are increasingly enmeshed in technology. New selfie techniques, with the help of filters and effects, enable us to modulate our body features or the temporospatial dimensions of our existence. You can now take a selfie on Mars while lying comfortably on your sofa.

Sci-fi Blockbusters often deploy reproductive love as a plot device to maintain human survival in the future (see Interstellar, Armageddon). Can queer imaginaries about invading space bypass anthropocentric demands for human survival or the quest for resource extractions? It might be useful to ponder: for what purpose would queers leave planet earth? To escape the constraints of heteronormativity? To build brave new worlds?

I placed these two selfies next to each other because I want them to be in conversation, to imagine an unlikely encounter. Alien encounters frequently function as a metaphor for encounter with the self (see Contact) or with the other (too many to list here but Arrival is a good start). Since queer life usually play out as alienation, the queer identification with aliens should come as no surprise.

Juxtaposing these two selfies evokes a host of questions about futurity through a queer lens. What if the two creatures in these two images meet: a human in space encountering an alien. What language would they communicate in and how are they going to establish the necessary basis for it? How would the human explain the queer experience on earth to the alien? How would the alien respond? What will happen next?

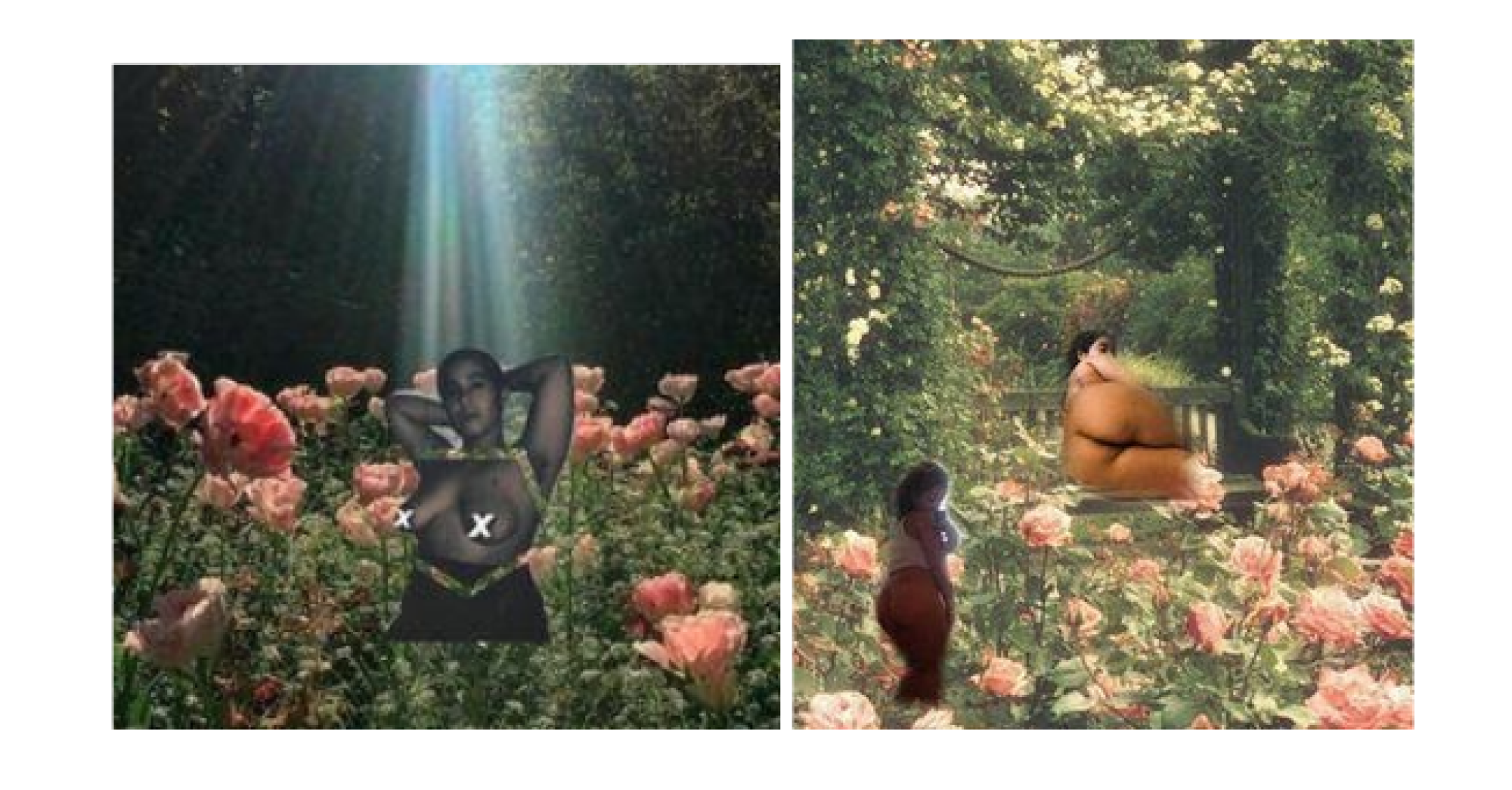

queer_selfies_4

Left: The subject stands topless and stares into the camera. Her arms are raised and hands placed behind the head. Her body is in black and white while the background is a colorful rose garden. A ray of light descends upon the subject creating a halo effect. Photo courtesy of Caribe Lunar

Right: Two images of the subject are inserted on a flowery garden background. In one image, she is lying down; she is standing in the other, looking over her shoulder. She is wearing a top while the lower body is undressed. Photo courtesy of Caribe Lunar

screenshot_2022-02-02_at_11.20.19.png

Left: The subject sits on the edge of a bed, holding his phone as the reflection of his naked body is captured. In the reflection, the electricity plug covers the genital area. Photo courtesy of artist Varun Singal

Right: The subject lies naked on a bed in a sitting position. His leg is under his body while he leans slightly forward, staring into the camera. Photo courtesy of artist Varun Singal

The politics of exposing the body on social media can lend itself to hegemonic power, reproducing oppressive beauty standards. White, cis, fit (whatever that means) bodies are privilged. This is evident from so-called community standards on social media, adamant to enforce strict values, while deplatforming certain bodies and sexualities. The stakes of showing bodies that transgress these norms are high and can result in censorship. However, such images are reminders that bodies, in all shapes and forms, exist. They are also a reminder of how the majority of the world looks like. This is a brown planet.

Thirst trapping is a subcategory of the selfie genre, modulated with specific lighting and angling, to entice and titillate the viewer(s). They evoke conflicted ideas and emotions. Posting a thirst trap can be linked to changes in body chemistry, triggering the release of pleasure neurotransmitters, similar to the processes involved in actual body contact. This has propelled some scientists to warn of its addictive potential. Others reject this as sex-negativity, pointing out that such reward pathway underpins social media use regardless of content.

Thirst traps could signal investment in erotic capital, an awareness in young queer populations of the virtual flows of desire markets. However, our understanding of thirst trapping keeps growing and shifting as the ambivalence of the motivation driving this phenomenon is revealed. Thirst traps can be taken (or posted) as: an expression of gender/sexuality, a process of self-acceptance, a boost to self-esteem and receiving validation, an avenue to generate income, to forge new sociosexual connections, to spite an ex-lover, and the list goes on.

Dubbing this subgenre “thirst traps” connotes a sense of a longing, or even desperation; an affect looked down upon, understating its value, writing it off as a sign of failed queer intimacies. To reject such notions, I refer to Shaka McGlotten’s concept of immanence2 (Virtual Intimacies, 2013) to recast light on the potential of thirst traps in creating queer kinship social interactions on virtual platforms. Thirst traps then could be instead read as forging new kinships and ushering innovative sexual practices. It might be worth wondering: if you press one finger on a mobile screen to pause a thirst trap fleeting on your Instagram story, would that be considered foreplay? What if you used two fingers to expand the photo size?

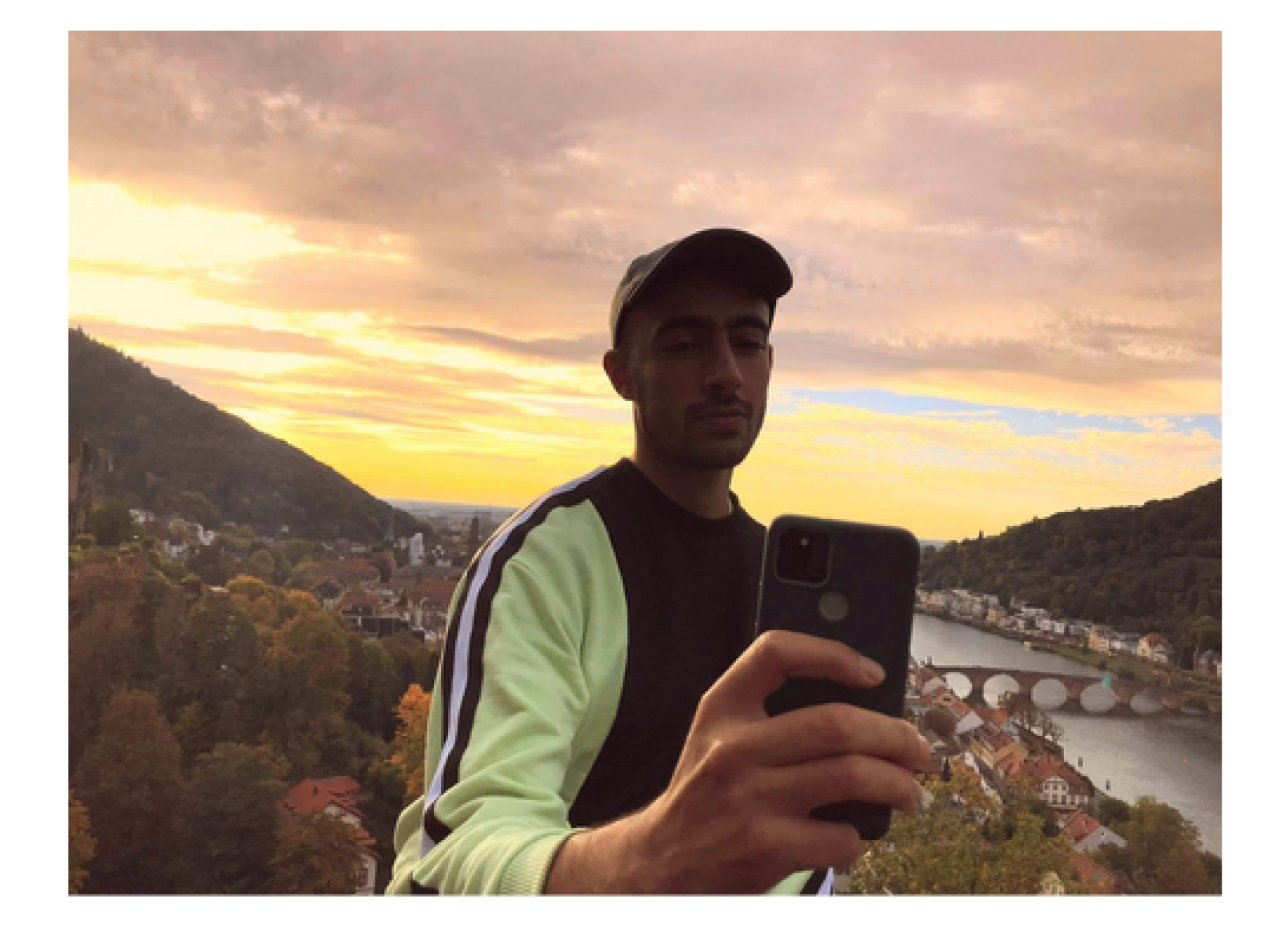

queer_selfies_5

The subject holds a phone in a moment of capturing the self. The background contains a landscape of a river and autumn-colored trees, during a sunset. Photo by Ahmed Awadalla

queer_selfies_6

Left: The subject sticks their tongue out, their face covered in sunrays as the background shows a monument of Otto von Bismarck, a Prussian politician and the mastermind of German unification. Photo by Ahmed Awadalla

Right: The subject looks down as they wear a taqiyah (muslim headcap). Behind them is a map on the right side, while the left side reveals a sign on the wall that says Notausgang (emergency exit). Photo by Ahmed Awadalla

What photos do migrants send to their families and loved ones back home? This was the topic of conversation with a friend whose parents were Turkish “guest workers” in Germany – a common term for those who moved to Germany after the second world war to seek work as part of a formal guest worker program. One of their dreams was to make more money to secure a better future. To reassure those at home, the photos were to build worlds where migrants were experiencing upward mobility and access to wealth. The photos usually depicted these migrants posing in front of fancy houses, fancy German cars, or spectacular landscapes. In reality, these houses or cars didn’t belong to them, and their work conditions were demeaning and dire.

I moved to Germany in a different time and space, triggered by a different set of concerns. However, the choice of photos I was sending to my family in Egypt followed a similar logic. They portray a different reality from what I share with my social circles in and beyond Berlin. It can be argued that the gap between the former and the latter is affective: one portrays prosperity as opposed to the other that depicts the conditions of forced exile and racism encountered in Germany. As Sara Ahmed shows,3 being a migrant who speaks about racism makes you a melancholic migrant. Such melancholia destabilizes the narrative that queer migration from the third world to western nations means a move towards safety as well as happiness. Is melancholia the sole affect of queer exile? The answer is no.

The visual representation of queer exile expressed here recreates an impermanent mode of dwelling, one where there is no settling down or comfortable home. One that gazes downward upon the mythology of an imaginary, superior Europe.

queer_selfies_7

The photo shows a quotation from the artist Banksy which says “I don’t know why people are so keen to put the details of their private life in public; they forget that invisibility is a superpower.” Photo by Ahmed Awadalla

The issue of visibility generates tenacious discussions in queer activism and theory. While visibility is deemed in some circles as necessary for the advancement of queer rights, this view is criticized as eurocentric, underpinning a linear progress narrative – one where the legitimacy of queer lives is only possible through revealing the self. As is evident by the lived experiences of queers in different parts of the world, visibility could trigger more control, punishment, and backlash. Visibility also contributes to the rising of commodification of queer lives in the name of diversity and inclusion, also known as rainbow capitalism.

Taking a selfie is a way to say “I was here,” leaving a trace, leaving a mark. Selfies do require an exposure of the self, but can this self remain somehow opaque? These entries question the ostensible inefficacy of invisibility and offer alternative roads. They evoke a different kind of closet, one from which the subject watches back, one where plots are planned. A world that oscillates between visibility and invisibility.

- 1. Sandbye, Mette. “Selfies and Purikura as Affective, Aesthetic Labor.” Exploring the Selfie: Historical, Theoretical, and Analytical Approaches to Digital Self-Photography. Edited by Julia Eckel, Jens Ruchatz, and Sabine Wirth. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- 2. McGlotten, Shaka. Virtual Intimacies: Media, Affect, and Queer Sociality. New York: SUNY Press, 2013.

- 3. Ahmed, Sara. The Promise of Happiness. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010.