A Revolutionary Counter-Archive of Illustrations

statue.jpg

When we make vertical power horizontal

Tell me your story توهم

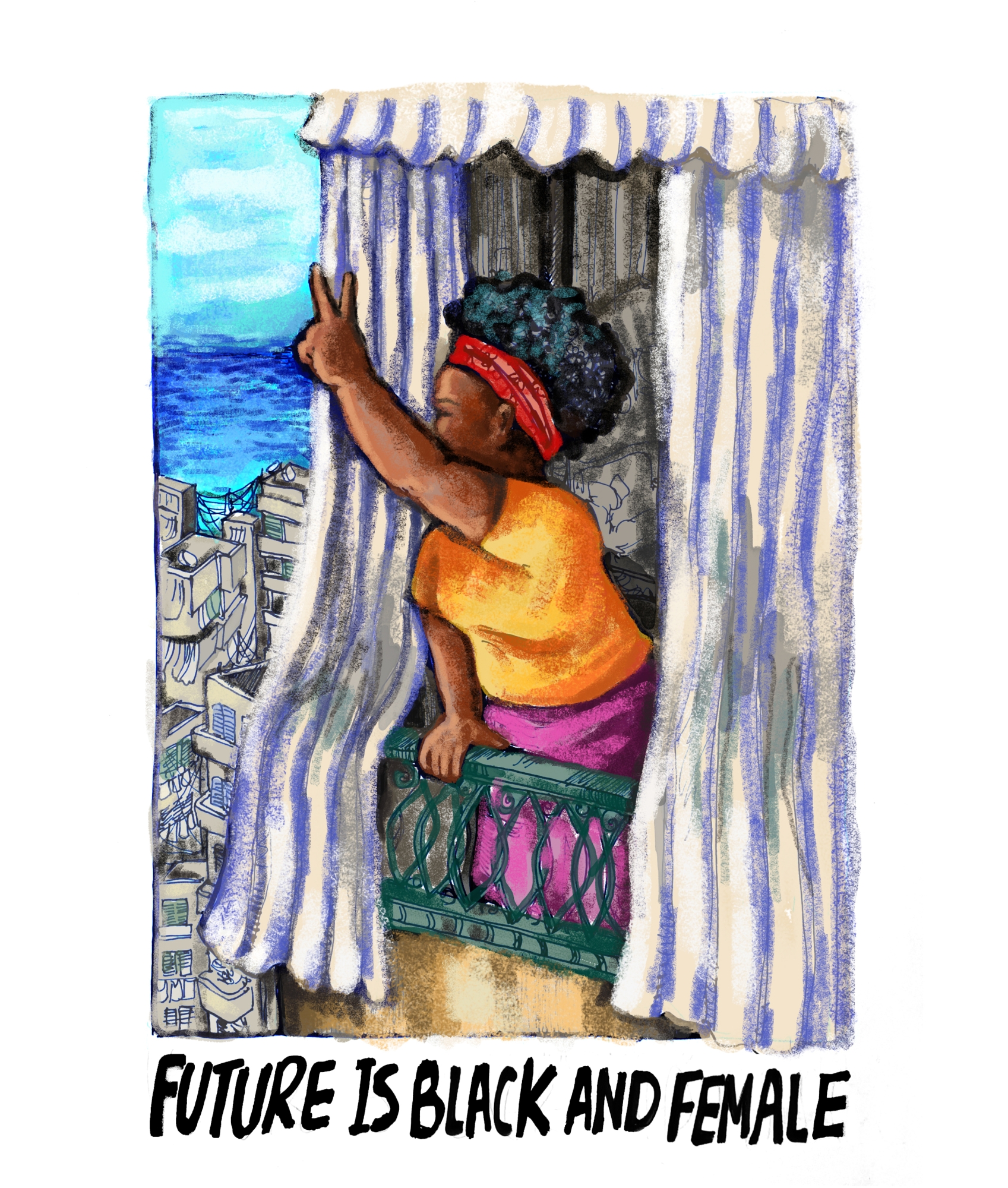

Black Beirut

Black Beirut is a phenomenon that I’ve heard from Sumayya Kassamali for the first time, in Beirut in June 2019. Sumayya Kassamali is an anthropologist whose work focuses on urban violence and migration in the Middle East. She holds a PhD from Columbia University (2017) and is a postdoctoral fellow at the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard University. She defines black Beirut like this:

“Over the last decade, increasing numbers of African and Asian women who arrive to Lebanon as migrant domestic workers have escaped the homes of their employers, to whom their legal residence in the country is tied, and entered the urban working classes of the Lebanese capital. There they have recently been joined by thousands of men fleeing war in neighboring Syria.

Together, they have built a layer to the city of Beirut that has transformed both the city and the lives of the workers who keep the city functioning. Theirs is a city where Bangladeshi grocery stores open in a Palestinian refugee camp, Ethiopian women marry Sudanese refugees, Filipina women invite Syrian construction workers to join them for karaoke, and everyone shares cigarettes waiting in line for visiting hours at ‘Adliyye detention center. This Beirut is publicly visible to an extent, but its internal operations rely on learned codes and guarded entry. It is multi-lingual, multi-national, and multi-ethnic, and it is surely one of the most diverse corners of the entire Levant. Its spatial centre is the adjacent neighborhoods of Bourj Hammoud, Dawra, and Ras el-Nab’aa, and its temporal climax is Sunday, but it is a network spread throughout the city and beyond. It includes small side streets in one neighborhood, a church and the alleys that spill out from it in another, private schools that transform into flag-filled celebrations for different nations, outdoor stadiums that host international pop stars for migrant audiences, catering services for home-cooked cuisine, sports teams and fashion competitions and niche social clubs, as well as ways to smuggle cell phones, sewing needles, and hair extensions into prison. It is a thriving underground, but it is subject to constant harassment and the threat of forced closure at the hands of both state and society. I call it ‘Black Beirut’.

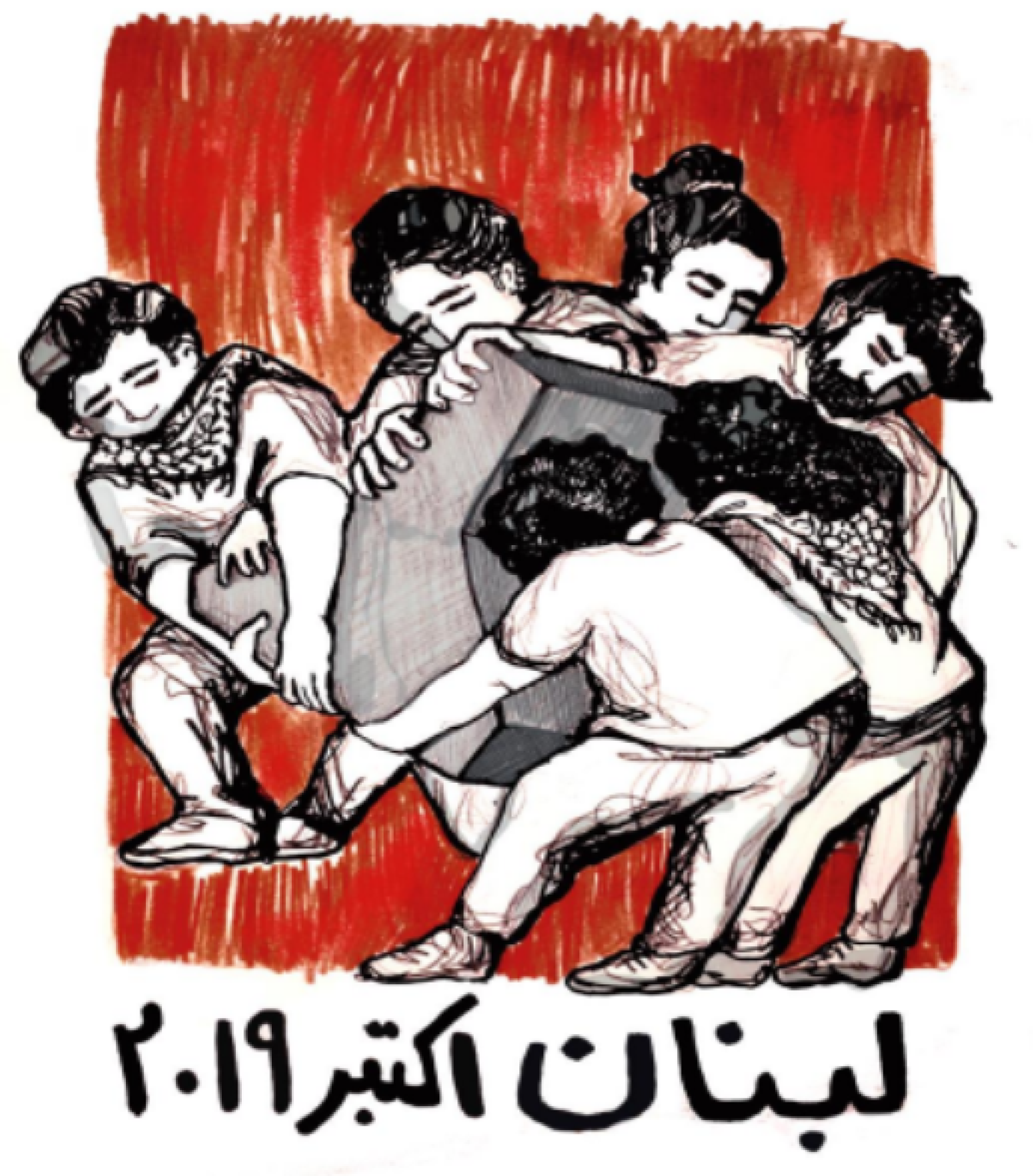

The failing of impossible

When our collective will desires to liberate emancipation from fear, the meaning of the impossible can change forever. The will born in Lebanon twenty days ago is now filled with waves of fears and hopes that thousands of people in Lebanon are living with, from morning to night, from peaks to downfalls. Along with new meanings forming every hour, people sing, dance, and chant together, as the very significance of the impossible massively changes alongside. All the things that seemed solid and unchangeable are shifting matter one after another: movements, forms, words, beliefs, and ultimately the revolutionaries themselves, who are the creators of this new space. From being fragmented creators, they acquire a new body of togetherness. The street, our commonplace and the source of what is impossible for our bodies, has become a stage in Lebanese cities for the mass to perform this togetherness. Then, the revolutionaries conquer those same streets that were always heavily militarized, populated with numerous and unnecessary gates, blocks, and chains, to announce after thirty years the end of the civil war nightmare.

Among the many extraordinary images of this collective will was that of men and women in Riad Al Solh Square moving the heavy, immobile cement block to use it as a stand in their tent. At that moment, I realized that I had always naively thought that it was impossible to move this heavy urban object. The irreversible heaviness was shaped by the observation of my individual body – an observation it forever forgot after it was moved by the collective.

Golrokh Nafisi 27.10.2019

Beirut