Migrating at 40

Translated by Yasmeen Mobayed

Translation edited by Ghiwa Sayegh

2-_tell_me_your_story_twhm.jpg

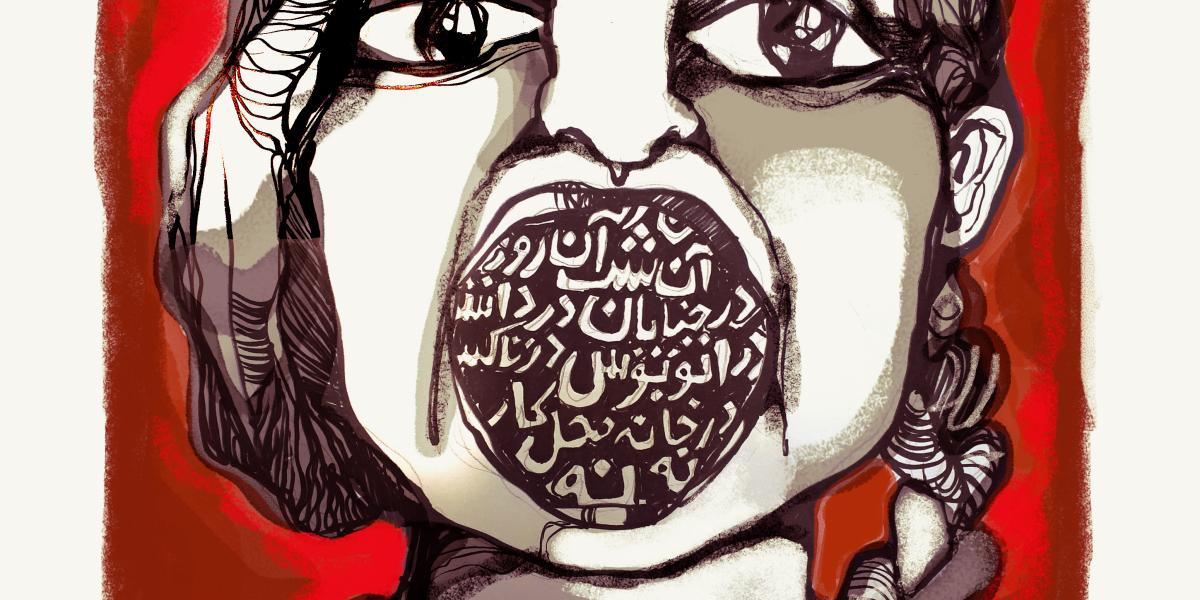

Tell me your story توهم

I settled outside of Beirut five years ago, in an area that became familiar and that I grew to love. After a long struggle, my inner world had quieted down – my choices and relationships matured as the trees around me gained in density and strength. The little house with a garden and two pine trees was situated at an acceptable distance from Beirut – enough to get away from the city without completely severing my relationship with it. It seemed like things were falling into place. Steadfast friendships that aged well despite the intensification of misfortunes, lingered still. A beautiful, slow, new job. Love that pulls at the heartstrings. A body that finally began to recover from the impact of toxic relationships. My mother, who started to love her life and whose wholehearted laughter made me love myself in turn.

Are growth and self-reconciliation the features of our 40s? I had sought to create a bubble that fits me with all my fluctuating moods, my medical prescriptions, and my friends and their laughs and our many tears. The bubble helped me overcome personal shocks and political tensions without entirely collapsing and remaining frozen for years to come, as was the norm. The bubble reconciled me with my existence in this geographical context and muffled the emigration1 bell that rang each time a crisis troubled our paths.

I wanted to leave Lebanon ever since I graduated from school. In 2000, I enrolled in a university in Canada, but never went. In 2005, I was “emigrating to Australia.” In 2010, I was planning to “continue my studies in Belgium” (but then, I still continued them in Lebanon anyway). In 2017, I completed my freshman year in France – which turned out to be the last. These were attempts to escape during years of compounding, consecutive crises. Meanwhile, with each failed attempt, it became increasingly difficult to adapt to the turmoil in Lebanon. Some of these attempts failed because of patriarchal, emotional blackmail and newborns coming into the family. Others failed because I despise the cold and the snow, or were cut short because of an inebriated decision. Here I was, at the turn of a new decade, without any work, healthcare, or retirement securities, still living in a political context of perpetual instability. But I no longer had the will to undergo the emigration process, with its testing of patience, good faith, and good behavior that are demanded of migrants to maintain on top of their pains. The very sight of an immigration application made my stomach churn. “I have lived longer than what I have left.” This was the slogan of my willing surrender for what would come next. I surrendered to the little that suffices, and that I had patiently collected and guarded after a long journey of security, political, social, professional, and personal turmoil. I wanted to enjoy what remains of the beautiful corners of the country and anticipate the worst whilst alongside my family. This was how I comforted myself and justified my failure to escape.

I sank into the chair under the shade of the two pine trees. In the horizon, a faraway cloud and the peak of Sannine. I loved my bubble and wanted to grow old in it, quietly. After 39 years of struggling to survive and searching for havens of serenity amidst this carnival of perpetual tension, I felt, for a moment, like I was the owner of my life.

The October uprising happened, and despite everything, it was the most beautiful thing I experienced since the liberation of the South in 20002 and the return of Ziad Rahbani3 to the stage in 2012. What was the love I carried for this country, the people living in it, and our differences? Why did I smile at strangers in the street and feel the urge to sit and talk to them? Whenever I was in the middle of a crowd, I would feel a lump in my throat and find myself withholding tears. So, I would cry out the angry slogans written on the walls. However, the momentum in the street dwindled without achieving much. I hurriedly returned to my bubble.

Afterwards we were afflicted with an isolating pandemic, and again, I sat with my loneliness. I discovered then that I do not mind loneliness so long as it is inside my bubble. These must be the effects of the calm and balanced 40s! I said to myself.

Then, on August 4, Beirut exploded. In a single day, I aged fifty years. My bubble popped and I was hurtled into the abyss in freefall. I am a sad, ninety-year-old woman, lost in thought all day long, gazing into nothingness, short of breath, and only able to express herself in limited word counts which come out almost inaudible, barely above a whisper.

Life quickly transformed into a bottomless pit of anxieties: weekly battles with the bank employees and daily panic about rising prices and how easily our food and medications can slip away. My mother’s pension became worthless. I did not have health insurance. My sister got fired from work. I was assailed with messages like “stock up on flour,” “security incidents expected soon,” “I must inform you of the new price of the rent.” Tension was palpable in the streets, in supermarkets, in pharmacies, inside our homes, in the queues, at the doors of hospitals.

Dread spread everywhere. At a work meeting, I was asked, “how are you?” I broke into tears and for a few moments, the meeting paused. I received digital hearts and sensed the throats of my colleagues constricting behind their screens. My focus was depleted, my productivity nonexistent, and I had no desire to do anything at all. I felt stuck, emotionally and physically. Had I become over-sensitive? Was I depressed? Or had we reached our capacity, as the post-civil war generation that lived all the wars and battles since?

When I look at my face in the mirror, I see the disoriented 90-year-old woman. I hear her whispers. I am unable to abandon myself to tears, despite the searing migraines that resemble my mother’s. She had complained about them throughout my childhood and adult years. We are becoming like our parents in our ailments, bodies, and wrinkles. In Lebanon, our souls mirror those of people in their 60s and 70s, despite us being in our 30s and 40s. Our traumas, health, living conditions, and anxiety speak to each other across generations. In 2020, we reenacted their habits of stocking up on bread, water, and canned goods beyond our immediate needs. We had not realized we were taught this gesture as a remnant of the war, until we found ourselves worrying about replenishing depleted reserves. We resemble them in our tendency to be lost in thought and to stumble on words when someone asks us how we are doing. We resemble them in our lack of ambition and vigor, in our looks of helplessness and need. We resemble them, too, in our packed luggage and briefcases with all our essential documents, always ready to flee, either to a bomb shelter or abroad.

Part of growing up meant always bracing ourselves for the worst that was yet to come. I have not seen my family members genuinely smile, except in videos that were recorded before I was born. I know their anxiety well: I was raised in its shadow and struggled to escape its clutches for 39 years. And when I finally thought I had succeeded, I was struck by the same country, for the same reasons, with the same violence.

The decision to emigrate now feels more like the finishing blow that knocked me to the ground. What I feel is not guilt, but a detestable feeling of coercion. I am forced to leave so I can recover a semblance of emotional and mental balance, far from what and whom I love (how sad this sentence is!), so I can restore some of my productivity, so that I do not lose my job, my career, and myself. I want to look in the mirror and see my face again. I want to live my 40s the way my tired self wants to and deserves. Yet, I leave by force, submitting to a helplessness that afflicted those of us whose breaths were cut short for feeling too much hope a year prior.

I will turn 40 the week after I settle in the new country. Will my body manage with the differences in the air, weather, water, and noise? Will I dare to have a new mode of living? To trust new people and doctors who do not know my ailments and allergies? To walk on new streets, to enter homes with unfamiliar smells, to wander in places where I have no memories? The prospect of starting from scratch is painful and exhausting. What about my own self that I had only begun to decode? How will I cope with the additional stress of emigration? Whom will I continue my therapy with? Who will inherit my two pine trees and the sick jasmine bush in the garden? Will my mother be able to visit me? If so, when? What if uprooting and grief turn into depression? How will I reach my friends’ comforting arms?

The moment I reach the new place, I start looking for the Lebanese channels I hated on satellite TV. I display thyme on the kitchen table and pour olive oil on top of it. I burst out in tears to the voice of Fairuz. I do not want to lose my accent; I do not want to stumble on words either. My throat constricts every time strangers tell me, “Lebanon is beautiful, may it recover!”

I did it this time. I escaped. At 40, I am a stranger in a strange land. Now, I look in the mirror only to find a face without features staring back at me.

- 1. This particular translation (emigration rather than the term immigration) was deliberately chosen with the purpose of accentuating the conundrum in the act of leaving/abandoning/fleeing from one’s home/land, which is the focal question/theme of the Arabic text (Translation Manager).

- 2. The liberation of South Lebanon from over 20 years of colonial Zionist expansion and occupation (Translation Manager).

- 3. A leftist Lebanese musician, composer, script writer, actor, and political radio commentator (Translation Manager).