The Israeli Occupation and Palestinians’ Right to Choice in Marriage

Cover Website.jpg

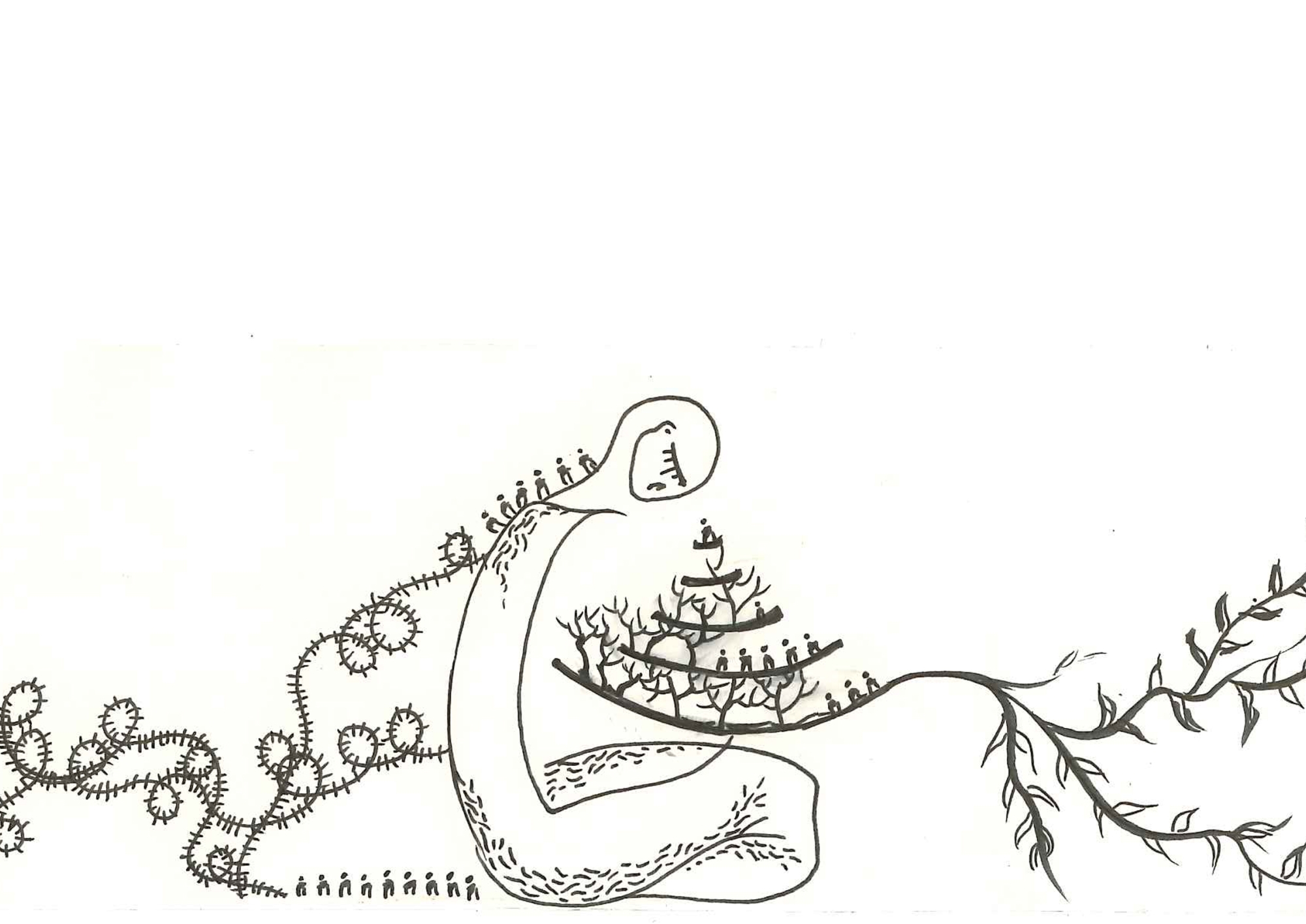

Illustration by Zeina Hamady 2018 ©

The right to choice in relationships is guaranteed by The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international treaties for all parties involved. For women especially, the importance of the right to choose a spouse was emphasized by the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Oftentimes, this right is compromised by the heteropatriarchal ideology that dominates Palestinian societies, just as is the case with other societies based on a normative notion of the nuclear family. But in the lived realities of Palestinians, the choice of partner is further complicated by the Israeli occupation, whereby relationships and marriage transcend their social fabric to become political struggles.

In order to contextualize the landscape for the reader, it is essential to first expose the dominant political reality in Palestine: the geopolitical division and partition of the land combined with the struggle to reunite separated families affect Palestinian women, conferring on the right of choice in marriage and relationships an additional political layer.

To maintain its grip over Palestinian societies, Israel founds its politics on a mechanism of population control that encompasses the right to citizenship and to choice in relationships, irrespective of gender. These politics are rooted in the practice of displacing Palestinians via making the conditions to grant them citizenship hard to meet. With the judaization of Jerusalem, this is especially applicable to Palestinian Jerusalemites, but also to Palestinians who reside in Area C, as I will later explain.

Palestinians’ right of choosing a partner is subjected to a politico-legal reality imposed on them by the occupation. Its political division of Palestinian land erects numerous hurdles and challenges when it comes to Palestinians’ choice of spouse. Since 1948 and until today, Palestine has undergone a series of geopolitical partitions that are geared towards the erasure of Palestinian identity. The additional administrative divisions (A, B, and C) that resulted from the Oslo Accords on the one hand, and the ongoing political isolation of the Gaza Strip since 2006 on the other, both complicated Palestinians’ right to choice in relationships and the struggle for reuniting separated families even further.

Despite the Oslo Accords, the Occupied Palestinian Territories today fall short of being an autonomous state with defined borders, political and economic independence, and control over their land and resources. In 1967, the occupation tore into the West Bank and divided Palestinian territories, including Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip.

In the wake of the 1993 Oslo Accords and the Oslo II Accord, The West Bank was divided into areas A, B, and C. Each area’s different governance structure also implies a different jurisdiction: while Area A (18% of the West Bank) is under the administrative control of the Palestinian authority, Area B is under the joint military and administrative rule of the Palestinian authority and the Israeli occupation. As for Area C (more than 60% of the West Bank), it is entirely controlled by the occupation. The West bank also follows a system of Israeli cantons. For instance, the canton H1 in al-Khalil (Hebron) is administratively governed by the Palestinian authority, while the canton H2 (20% of al-Khalil) is subjected to the occupation rule. On the other hand, the city of Jerusalem is not recognized as Israeli territory, as upheld by international law. Yet, Palestinians living in Jerusalem are given the status of “permanent residents” by the occupation, and live in constant harassment and fear of forced displacement and expulsion. The discrimination of Israeli jurisprudence against Palestinians and its denial of their right to choose a spouse and start a family come as no surprise: the occupation itself is rooted in refuting and erasing Palestinians’ indigeneity. Within that context, separating existing Palestinian families and preventing the formation of new ones become common practice. Palestinians who hold blue identity cards live either in the J1 area, the part of East Jerusalem that was annexed to the Israeli municipality of Jerusalem after the 1967 war, or in the J2 area, the Palestinian parts of East and North Jerusalem that are densely populated and do not belong to said municipality. There, they are denied their basic rights to residency, adequate housing and shelter, freedom of mobility, health, employment, education, and family life. Additionally, Israel’s legislative measures compromise the right of Jerusalem’s Palestinians to residency, a status that is necessary for them to remain in the city, with the aim of displacing them outside the borders of city.

In all of A, B, and C divisions, the fragmentation of the West Bank’s rural areas was made possible via the Israeli permit system, the apartheid wall, and the installing of roadblocks and checkpoints. The Zionist entity that separated the West Bank from the Gaza Strip exercises a complete control on and blockade of Gaza’s land, air, and sea. Since 2008, Israel has waged three wars on Gaza, bringing utter destruction to both human life and infrastructure.

The Zionist entity’s full dominion over the Palestinian territories creates a material reality whereby its control is sustained via a mechanism that violates Palestinians’ right to family life and to choose a spouse. In Jerusalem, Palestinians’ life is regulated by two types of restrictions that violate family reunification. The first one dictates that if one spouse carries a blue identity card (held by Palestinians living in Jerusalem under Israel’s political and legal control) while the other carries a green one (held by Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza), they cannot live together in the J1 area. In the event that they choose to remain in the J1 area, the partner without the blue ID would live in fear of deportation from the city. These conditions disproportionately affect women, as they also have to contend with the heteropatriarchal social norms that restrict their freedom under the guise of culture and tradition. Many of the women whom I have met as part of my activism in women’s rights resort to drastic measures, such as confining themselves to their homes and restricting their own mobility. Under occupation rule, they are considered to be living illegally in the J1 area, which affects their rights to work and education, among others. From supposed havens of safety, independence, and stability, their own homes turn into their prison. This especially holds true for Palestinian women who have to follow their spouse’s place of residence, as per Palestinian societal norms. One of the women with a green ID who married a Jerusalem resident said:

I have missed so many family occasions in my parents’ house in Hebron. They also could not visit me because they could not obtain a permit to cross the military checkpoints. Since I do not have a residency permit for Jerusalem, I could not apply for a driving license or seek employment within Israel.1

Because of the reproductive role attributed to and expected of women, their confinement to the home and their limited mobility are not only normalized by their communities, but perceived as more respectable. They are considered to be a move that accepts to endure the political reality of occupation and its policies, and contributes to the Palestinian struggle locally. The occupation’s restrictions on the right to nationality and to choose a spouse contribute to further marginalize and exclude women from public life. Women, therefore, are subjected to the double violence of patriarchal hegemony: they become victims of their family and society, and the occupation.

On the other hand, in order for the spouse to retain their blue ID, the couple might resort to living separately, enduring a forced separation that can last for years. Children, if any, will subsequently be separated from one of their parents. Thus, families might consider the right to choose a spouse a nuisance due to the difficulty of obtaining residency in Jerusalem or elsewhere. A mother who holds the blue Jerusalem ID expressed the following:

I would prefer my daughter to marry someone with a Jerusalem residency permit, because it would be difficult for the family to reunite if the groom was from the West Bank. Should my daughter choose to live in the West Bank with him, she would lose her resident status in Jerusalem. In other words, it would become difficult for her and her children to visit us in the future.2

Women bear the brunt of these different lived experiences, and the exchange of such stories prompts both parties to reconsider their choice of spouse based on the potential spouse’s geopolitical location.

The second type of violation to family reunification has to do with couples who choose to live together in the J2 area or in another city in the West Bank. In that case, the spouse who holds a blue ID risks losing their status of Jerusalem resident. In turn, that would temporarily prevent them from applying for family reunification, as such an application can only be submitted after two years of consecutive residence in the J1 area. A woman from East Jerusalem described the experience as limiting to her freedom of choice:

My family did not agree to my marriage to the man I love because he was from the West Bank. They refused to let me compromise my Jerusalem residency, especially that I cannot guarantee, even after marrying him and applying for family reunification, that Israel would grant my husband a residency permit in Jerusalem. So my parents opposed the marriage and I cannot go against them.3

The same applies to Palestinians living in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, as mobility between the two is only possible if the Israeli authorities issue entry permits, which they seldom do. Because of the deliberate isolation and division enforced by the occupation, Palestinians’ right to choose a spouse from the West Bank if one is from Gaza, and vice versa, is extremely limited:

Because of the enforced isolation of Gaza, it becomes difficult for young people from the West Bank and Gaza to get to know each other. Even if marriage is on the table, residency is one of the major hindrances, as obtaining one for either the Gaza Strip or the West Bank requires many attempts. (A woman from the Gaza Strip)4

The rule of the Zionist entity exercises a complete control over the registration of Palestinian residents. Palestinians cannot issue birth certificates, identity cards, and passports without the prior approval of the occupation powers, a process further complicated by Israel’s deliberately convoluted bureaucracy. Hence, the difficulty in obtaining documents, certificates, and permits deters Palestinians from planning their future, as it hinders their right to choice in marriage among others.

Few studies have looked at the impact of the Israeli-imposed geopolitical isolation and divisions on the right to choice in marriage, despite its intersections with women’s fundamental rights in particular, and those of Palestinian societies in general. The citizenship of Palestinians is further compromised by the passing of a nationalist law by the Zionist Knesset. The law proclaims the “nation-state” to be a “Jewish nation-state,” granting Jews a unique right to self-determination, and denying Palestinians’. It also declared Hebrew to be the main language of the state, thus marginalizing the use of Arabic. This apartheid law seeks to ethnically cleanse Palestinian identity and the existence of a Palestinian entity.

Palestinian human rights organizations strive to shed light on the many violations Palestinian women are subjected. To that effect, they work towards submitting international reports to various international committees, such as CEDAW, the Committee on the Status of Women (CSW), and the Special Rapporteur on violence against women. Despite the numerous recommendations of the United Nations, Israel’s adoption of the “Jewish nation-state” law is but the latest violation in its continuous infringement on the human rights of the Palestinian people.

- 1. From the archives of the Women’s Centre for Legal Aid and Counseling (WCLAC), 2016. http://wclac.org/wvoices/511/women,s_voices_shireen_family_unification

- 2. Ibid.

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. Ibid.