On Alienation and Bitterness: Thinking Through Dhat with Latifa al-Zayyat

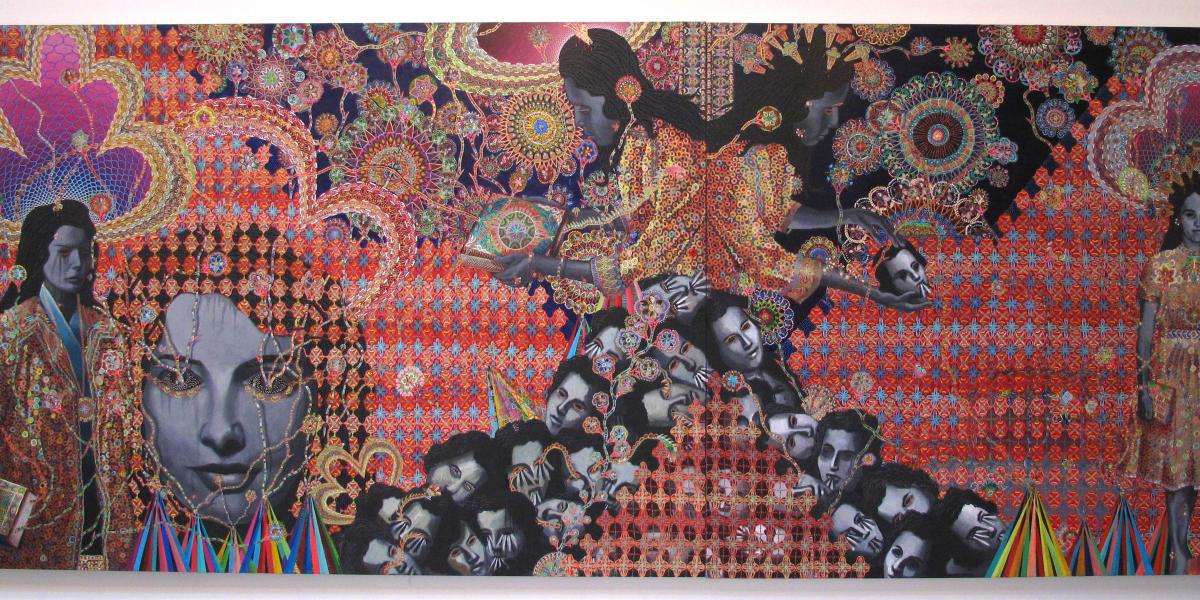

les_femmes_d_alger_20_60x144_2012.jpg

Les Femmes D'Alger, 2012

Sonallah Ibrahim’s monumental novel, Dhat, remains a landmark of contemporary Egyptian literature. Bringing to life the political and economic changes that swept through Egypt from the 1950s onwards, the novel follows Dhat, an average Egyptian middle-class woman, as she grows up, attends university, gets married, and has children. What is of particular interest is the way the novel centres the home as a locus of change; throughout we see the political and the economic through the intimate, bringing to the surface forms of labour and care that are often hidden from view.

The novel has been engaged with and reviewed many times, and what we introduce here is a review by renowned Egyptian writer Latifa al-Zayyat, published in 1992 in Adab wa Naqd (Literature and Critique).1

This review opens up a conversation between these two prominent authors, both of whom have written in particular on Egyptian politics from a gender perspective. Latifa al-Zayyat’s most famous novel, The Open Door (published in 1960), represents the historical moment of anticolonialism and Nasserism in Egypt. It follows Layla, the protagonist, in her attempts to subvert and challenge gender norms through participating in anticolonial struggle and national liberation. The parallels with Dhat are clear: Sonallah Ibrahim’s novel similarly follows Dhat, and though it is not focused on political or anticolonial struggle, it does subtly attend to the subversion and challenges of patriarchy and capitalism in postcolonial Egypt.

Both al-Zayyat and Ibrahim can be read as politically committed writers, whether to feminism or communism, and this political commitment seeps through their novels in interesting and unexpected ways. In Dhat, the critique of Egypt’s turn-away from Arab socialism and towards the free market is threaded throughout, yet almost always presented to us through a centring of the intimate. A careful balance between the documentary (archival newspaper clippings) and the literary, as noted by al-Zayyat in the review as well as Samia Mehrez in a piece on Dhat, serves to maintain the “panorama” of what was happening throughout those decades alongside the intimate changes taking place in the home. Mehrez writes, “As we read Dhat’s individual history, which gradually loses any individual features because of its familiarity, we discover that it is conditioned and shaped by a collective history that unfolds through [the] newspaper clippings.”2 In what follows, we touch on three particular themes that al-Zayyat uses to structure her review of Dhat: alienation, bitterness, and the mask.

Why are we translating this particular text, and why now? We came across the text while researching a different article that explores capitalism and care in Egypt through Sonallah Ibrahim’s novel Dhat and Latifa al-Zayyat’s novel The Open Door. This review by al-Zayyat was a serendipitous find that brought the two authors into conversation, while also touching on many of the themes we have been thinking about together – in particular, the ways in which gender, capitalism, and labour manifest in postcolonial Egypt, and how fiction opens up important ways of exploring this as felt by Egyptians.

We were also struck by how al-Zayyat’s review is a social commentary of the misery of the 1990s, which emerges as she writes about Ibrahim’s focus on the misery of the 1980s. Al-Zayyat refers to Ibrahim creating a “panorama of the 1980s” and in her review similarly gives us an insight into how the 1990s were felt and experienced. As we write this introduction, we are conscious of the misery of contemporary Egypt, in 2022, and how this speaks to the decades that al-Zayyat and Ibrahim have so skilfully made sense of. Our introduction and translation, then, adds an additional temporal layer to Ibrahim’s novel and al-Zayyat’s review, providing a continuity that speaks to the conditions of capitalism and dictatorship past and present.

Alienation

Sonallah Ibrahim’s novel does not seem to have a clear beginning or end, and every day seems to be like every other day. As al-Zayyat writes,

The chapters follow each other, one documentary, one fictional, with the exception of the last chapter that concludes the novel. I hesitate here in using the expression “conclude the novel” for the novel ends, so to speak, without a conclusion that culminates from an event or a climax. (…) The novel could have ended at this point or at another without disrupting the event for the conclusion isn’t an ending to a brewing tension or struggle throughout the novel, nor does it follow a particular organic structure that could fall apart if we exclude or change a detail or another, as Aristotle would put it.

Just as the novel could end at any point, so could its beginning. And indeed, this is what the writer sarcastically confirms in the opening pages of the novel, indicating that choosing this beginning is spontaneous or random, for all the days are like all the days, and nothing grows out of a tension. Nothing happens but this mad race toward ownership. In reality, nothing truly changes.

Al-Zayyat notes this in her review to bring to the surface the way time operates in the novel, as repetitive, routine, and stretched out; in other words, as mimicking the way time is stretched out in Dhat’s own life and labour. The theme of time is closely tied to that of alienation, as the repetitiveness and dreariness of capitalist time produces an almost out-of-body sensation with its own monotonous tempo. The novel is not made up of events or turning points; it is in this sense that although it starts in 1952, the year Dhat is born, it could have started any other year. The novel thus has an underlying tempo that is the tempo of labour under capitalism, a tempo that does not speed up or slow down but rather remains stubbornly constant and inescapable.

Yet if the novel could have started at any other time and if every day is like the other, it is still impossible to separate the writing from the context itself. In this sense, it appears to be both timeless and yet clearly written about Egypt at a particular historical juncture, that of the turn to the free market in the 1970s and 1980s. As al-Zayyat notes, the novel is a “panorama of the 1980s,” a decade still marked by the defeat of Arab socialism and the 1967 war against Israel – as well as global socialism more broadly. Yet the decade is not necessarily experienced through defeat, the way the late 1960s were; instead the turn to the free market was presented as an opening. The end of one collective national project was eclipsed by the ushering in of this new future promised by the free market, marked by Camp David and a shift in geopolitical orientation. The power of this turn to the free market seemed almost to be in the promise itself, rather than a material project; indeed actual processes of privatisation began much later than the announcement of them in 1974. This context of 1980s Egypt is part of the novel itself, including in the language being used – as al-Zayyat notes, new terms were being introduced with Infitah, changing the language and marking different relationships to the market:

The writer/narrator who mocks his characters and his material aims to deepen the feeling of alienation, constantly breaking away from the elements of illusion. As such, he is always interfering in the text, temporally and spatially interrupting the literary flow with frequent commentary. He blends the grand with the trivial, with repeated satirical references usually between parentheses of new linguistic creations that mark the Infitah and that are strange to the Arabic language, such as al-sarmakah (covering the walls with ceramics), al-kambashah (referring to the modern toilet), and al-kandashah (referring to the air-conditioner).

The timeless quality inherent to the novel is replicated in the main character of Dhat, who represents alienation in an extreme form. According to al-Zayyat, Dhat can be read as an anti-hero, a view held by Walid El Khachab (same volume), and Samia Mehrez, as well. Although the novel is about Dhat, we neither hear her speak nor see the world from her perspective. This device deployed by Ibrahim produces a feeling of alienation in readers, who are removed from the story itself. This is heightened through the narrator’s tendency to mock characters and employ satire, which deepens the element of alienation. Dhat is like any other woman; there is nothing about her that stands out and here we can read her as an anti-hero that disrupts the form of the novel. Just as there are no events, no starts and ends, there is also no firm main character whom we can experience the novel through. Social relations are thus developed through the plot and the tempo of the novel, rather than the individual “hero;” ultimately there are no main characters, no events, and no time.

Bitterness

As we progress through the novel, we notice that Dhat begins to retreat to the bathroom to cry more and more. These episodes in the bathroom are difficult because we see her come apart, bringing to the surface what we might describe as the bitterness she feels towards her life. Bitterness is not an event – the book does not have events – but is rather depicted through a very slow build-up. It isn’t possible to pinpoint when exactly it appears, it is suddenly there. This bitterness can be connected to the endless work Dhat has to finish: in the kitchen, at her job in the archives, for her side businesses, and the endless child-care and care work in the home more broadly. Dhat seems to be always working, and exhaustion soon becomes a defining feature of both her and the novel. This is mirrored in the decay of the city and the home itself, with peeling walls, shaky infrastructure, and leaking pipes.

The psychoanalytic themes in the novel are drawn out in relation to this notion of bitterness and resentment, to these feelings of exhaustion and dreariness. The bathroom is perhaps the most symbolic space where we see this being enacted; she keeps losing something when she goes back to the bathroom to cry or break down. The bathroom is also a confined space that cuts through the repetition of the different tasks of the household and the (labour) time put into those tasks. It is a space that gives the illusion of a pause or a break in time from the constant movement from one task to another. The bathroom as a sanctuary; in other rooms she is always surrounded by noise and people and demands. The bathroom itself is also falling apart, desperately in need of fresh paint and new tiles. This mirroring between her and the materiality of the bathroom is fascinating, and speaks to just how wide-ranging the novel is in presenting the “panorama of the 1980s” al-Zayyat writes about.

While the tempo of the novel remains constant, Dhat’s tempo shifts towards the end of the novel as she begins to slow down. The free market is thus represented less through what become possible or grand promises of the future, but through exhaustion and decay:

The novel ends when Dhat discovers that the fried fish and herring she brought home are no longer suitable for human consumption. This time, she throws them in the garbage, knowing from experience that filing an official complaint is a hopeless endeavour. One more time, Dhat finds refuge in her bathroom as she cries.

What we are left with is a slow coming-apart of both Dhat and Egypt, where faded promises leave little but bitterness behind.

Yet it is not just Dhat’s bitterness that al-Zayyat points to, but our own as readers. At the end of the review, she writes:

With the writer, we mock and laugh at the characters, but deep down within our laughter something bitter and painful remains. It is something that reminds us of the danger of slipping into this polluted space concerned with the fates and paths of these fictional people.

There is a tense, and frightening, point at which we might begin to see ourselves in the characters, to see our own worlds in the world of the novel. This point might arise multiple times, or maybe just once or twice. It is this possibility of recognition that creates a bitter and painful feeling in us, as readers. We recognise that the space is polluted, as are the lives of these characters; yet we know deep down that the distance created between us and them, discussed in the next section, is never quite as distant as we think.

The mask

For Bertolt Brecht, the mask is a deliberate act that alienates the audience and distances them from what is taking place on stage, while also eliciting a response from the audience.3 As discussed earlier in the section on alienation, the novel deploys various tactics to alienate the reader, from the tempo of the novel to a clear distance from Dhat and her life. As we read, we are both confronted with intimate details about Dhat’s life as well as the distance between ourselves and the story. As al-Zayyat writes:

On the one hand, Dhat remains a stereotypical character standing for millions of Egyptians resembling the other characters of the novel. On the other hand, Dhat does not have any personal traits that compel the reader to sympathize or identify with her.

The choice of Dhat as the main character of the novel (like the choice of the rest of the characters) and the type of event that the writer imagines and directs, establish an emotive space or distance between Dhat and the reader.

Dhat is both stereotypical and distant; she represents millions of Egyptians while also seeming far away from experiences readers might relate to. Ibrahim’s style and choice of characters produce this tension between familiarity and distance, creating what al-Zayyat refers to as an “emotive space” between Dhat and the reader. This distance is replicated by the narrator too: “Distanced from his characters as he ponders their paths, the narrator invites us to ponder with him. He mocks this path and again invites us to also mock with him. Ultimately, one of the novel’s main goals is satire, a goal that is indeed achieved in the text.” For al-Zayyat, the novel does not take an organic structure rooted in the unity of the event and its development from a specific moment to another, rather it takes an epic form based on alienation in the Brechtian sense of the term. She argues that the novel is not narrated from the perspective of the protagonist, Dhat, but from the perspective of a narrator, the writer himself. This, she argues, alienates us as readers from Dhat’s life, locating us outside the event, emotionally separated from it and observing it.

Masks also appear in the novel and al-Zayyat’s review through the idea that Dhat wears a mask that reduces her existence to the bare minimum: either a machine labouring, or a particular function she has to carry out, or a tiny part of her bodily form:

Indulging in his satire and the desire to alienate, the writer uses an artistic ploy similar to the characters’ use of masks in epic theatre. The character in this novel is not like a living person who is multidimensional and unique. She is wearing a mask that reduces her existence to a machine, a job, or an animal, or to parts of her bodily composition.

In this sense, masks function to not only create a distance between the reader and characters, but to reduce characters such as Dhat to their bodily composition. This in turn makes it difficult to sympathise with them, even if they represent personas we are familiar with, or experience events we have all experienced. This is the ingenuity of the novel and the review: Dhat’s non-character is in fact the central character of the book. The reader’s attention is drawn not to her, as a “multidimensional and unique” person, but rather to the particularity of her life as one stripped down to basic repetitions. Moreover, the use of the mask serves to highlight how inconsequential each character is, in turn highlighting the routine and incomprehensibility of their everyday lives. This also speaks to our earlier discussion of alienation: just as the novel could have started and ended at any point, the characters could have been anybody and everybody.

Al-Zayyat concludes her review by re-emphasising the novel’s delicate balance between fiction and documentary, how the fictional characters move and live within the material historical events of the period. Ibrahim and al-Zayyat are writers whose political commitments undoubtedly shape their fiction in one way or another; with Dhat we are unable to forget the political context within which this novel is taking place, and therefore unable to forget politics. We are distant from the characters, but also too close to them; indeed writing about and translating this review in 2022, we are still unable to separate ourselves completely from the misery described in the novel and the misery described in the review. We are still living with the consequences of Infitah, and it is in this sense that this novel could have started and ended now, just as it could have started and ended at any other time. Yet this is the beauty of this novel: it is both timeless and carefully grounded in the 1980s because of this delicate balance between documentary and fiction. An example of a work of fiction that is completely and utterly political, it reminds us of the power of fiction in politicising the everyday.

A Reading of Sonallah Ibrahim’s Dhat: Alienation, the Mask, and Bitterness

Dr. Latifa Al-Zayyat

Translated by Mai Taha and Sara Salem

Sonallah Ibrahim’s novel, Dhat, consists of nineteen chapters of narrative fiction and documentary that follow one after the other. The documentary aspect is a central component of the novel. The reader could be tempted to just turn the pages to follow the story, while ignoring its historical dimensions.

To avoid this, a novel needs a careful balance between documentary and fiction, so that the reader gets acquainted to both, each for their own. Without this delicate balance, both of those elements wouldn’t be able to assume their roles within the framework of the text, where together they produce the overall sense and meaning of the novel. In Dhat, Sonallah Ibrahim establishes this delicate balance with deep awareness of the nature of his material, and with an incredible social sensibility and ingenious technical ability.

The documentary aspect of the novel is particularly unique, making it a source of pleasure for the reader who becomes eager to follow this aspect more and more.

The writer establishes a pattern of succession between the narrative fiction and the documentary chapters. The reader not only accepts this pattern but looks forward to more of this fiction-documentary combination, as the novel unfolds. This is culminated in an incredible panorama of the 1980s, of which I have not known any parallel in Arabic literature. The novel thus performs its vital role in narrating the history of the period and situates its characters in their socio-historical context, and thus readers could make sense of their actions and behaviours.

The documentary aspect is constituted by hundreds of media excerpts curated with a shrewd social sensibility that captures the imbalances in the social and historical reality of the novel’s characters.

Sometimes, these suggestive media excerpts are categorized in a way that shows a social imbalance. But mostly, these excerpts are categorized based on the elements of identity and difference, showing the broader tensions in the social reality of the period in its entirety.

The reader may be aware of some or most of the details in those excerpts. But their accumulation and categorization on the basis of the elements of identity and difference produces a deeper meaning than the reader’s own knowledge, no matter how great it is. Indeed, every detail says something to the reader. Through artistic classification and accumulation, every detail gains an organic significance and gets embedded within a broader set of meanings that frame the displays of inequalities in society. In that sense, the novel narrates a complete history of the 1980s, showing the incompleteness of a regular, even if brilliant, fictional structure that is not complemented by the documentary and historical elements.

While the novel’s documentary fabric has its benefits, the writer still gets the reader involved in the fictional event, establishing this delicate balance between the fictional and historical elements of the novel. The writer’s intention here is also manifested in his choice of characters, the kind of event that he adopts, and his way of presenting it.

It is difficult for the reader to identify with any of the characters in Dhat for they are ordinary (or less-than-ordinary) people who only aspire to climb just a few more steps of the social ladder by acquiring recreational consumer goods that mark the period of Infitah. And if we pause at the main character of the novel, Dhat, we find that Sonallah Ibrahim chose a non-heroin. Indeed, Dhat has a thanaweyya ‘Amma (national high school) degree and is married to Abdel Meguid Khamis who can’t seem to pass his last exam at one of the universities. She is a regular employee who finally settles in the archive of one of the newspaper dailies.

Dhat is an ordinary person. In fact, with all her fears, ambitions, and obsessions, she is even less than ordinary, merely floating on the surface of events without having a role in their making. She lives a life of anxiety where her colleagues in the newspaper archive ignore her because she lost her self-confidence. She tries to regain their attention to no avail, again and again.

Like the other characters of the novel, Dhat is frustrated on all levels, including of course in her sexual and marital relationship. This sexual frustration represents here a broader frustration extending from Dhat’s husband to her neighbour and her neighbour’s husband. Dhat lives and moves among regular characters, some of whom make minor contributions to local corruption. But they make big contributions to the promotion of the values of ownership and competition over replacing the bathroom and kitchen tiles with ceramics, and over changing the furniture, among other manifestations of the consumerist era of the Infitah.

In terms of income, Dhat belongs to the middle class. She is neither poor nor crushed in a way that would have triggered our sympathies as readers. She is ambitious, like everybody else around her. And if she fails to persevere in the fierce competition that some of the petty cons within her neighbours engage in, at least she succeeds in registering her son in a private school, which gives her a temporary special importance. But she is unable to continue replacing her kitchen tiles with ceramics, leaving part of it bare. Indeed, this nakedness or incompleteness becomes a commentary on her financial condition, and on her unfulfilled ambitions during the Infitah.

On the one hand, Dhat remains a stereotypical character standing for millions of Egyptians resembling the other characters of the novel. On the other hand, Dhat does not have any personal traits that compel the reader to sympathize or identify with her.

The choice of Dhat as the main character of the novel (like the choice of the rest of the characters) and the type of event that the writer imagines and directs, establish an emotive space or distance between Dhat and the reader.

The chapters follow each other, one documentary, one fictional, with the exception of the last chapter that concludes the novel. I hesitate here in using the expression “conclude the novel” for the novel ends, so to speak, without a conclusion that culminates from an event or a climax. The novel ends when Dhat discovers that the fried fish and herring she brought home are no longer suitable for human consumption. This time, she throws them in the garbage, knowing from experience that filing an official complaint is a hopeless endeavour. One more time, Dhat finds refuge in her bathroom as she cries. The novel could have ended at this point or at another without disrupting the event for the conclusion isn’t an ending to a brewing tension or struggle throughout the novel, nor does it follow a particular organic structure that could fall apart if we exclude or change a detail or another, as Aristotle would put it.

Just as the novel could end at any point, so could its beginning. And indeed, this is what the writer sarcastically confirms in the opening pages of the novel, indicating that choosing this beginning is spontaneous or random, for all the days are like all the days, and nothing grows out of a tension. Nothing happens but this mad race toward ownership. In reality, nothing truly changes.

Instead of the Aristotelian organic structure that is based on the unity of the event and its development through tensions from one specific point to another, we find ourselves facing an epic structure based on alienation and estrangement in the Brechtian sense, where there are successive variations of the same theme establishing a wide emotional space between the event itself and the reader.

The Aristotelian organic event relies on the element of illusion and obliges the reader to embrace it and thus fully integrate into the event. As for the epic event, it intentionally and deliberately breaks this illusory element, preventing the reader, even if momentarily, from integrating into the story. This opens up the space for critique as it puts the reader outside the event, inviting them to try to change that event, but this time, in real life not in the novel. In that sense, the epic event, as presented here, is in fact a call for change.

The event revolves around “Dhat,” her husband, her friends, her relatives, her co-workers, her maids, and everyone around her and every place she moves to. But the event does not come to us from Dhat’s point of view, not even from a perspective that is close to hers or to that of any of the characters of the novel. The event comes to us from the writer/narrator’s point of view, in congruence with the epic structure that is built on alienation. Indeed, the writer/narrator places us and himself outside of the event, emotionally separating us readers from the story as we observe it from above.

The reader is, of course, affected by the writer/narrator’s relationship to his material. The writer/narrator is not in a position of neutrality that allows the reader to think and reach their conclusions. A writer who is troubled by his society and his people cannot be impartial, and therefore he constantly relates to his material with scathing irony.

Distanced from his characters as he ponders their paths, the narrator invites us to ponder with him. He mocks this path and again invites us to also mock with him. Ultimately, one of the novel’s main goals is satire, a goal that is indeed achieved in the text. Satire cannot be construed here as neutrality or indifference for the person who is concerned with his homeland and people could not claim impartiality neither in collecting his material, nor in his presentation of the literary event. In our time, the socially conscious individual is left with nothing but satire in the face of deteriorating conditions.

The writer/narrator who mocks his characters and his material aims to deepen the feeling of alienation, constantly breaking away from the elements of illusion. As such, he is always interfering in the text, temporally and spatially interrupting the literary flow with frequent commentary. He blends the grand with the trivial, with repeated satirical references usually between parentheses of new linguistic creations that mark the Infitah and that are strange to the Arabic language, such as al-sarmakah (covering the walls with ceramics), al-kambashah (referring to the modern toilet), and al-kandashah (referring to the air-conditioner).

Indulging in his satire and the desire to alienate, the writer uses an artistic ploy similar to the characters’ use of masks in epic theatre. The character in this novel is not like a living person who is multidimensional and unique. She is wearing a mask that reduces her existence to a machine, a job, or an animal, or to parts of her bodily composition.

Like the rest of the characters, Dhat is a broadcasting machine, transmitting news of the frightful race towards the Infitah. She shares and receives information, yet she is completely incapable of human communication or of sharing what is inside of her. And perhaps here Sonallah Ibrahim has pushed the boundaries with this euphemism for the novel’s characters, or rather this euphemism for what we have reached as a society within the hustle and bustle of life, and in light of the economic, political and social changes. Indeed, we now talk and imagine that we are communicating; our words connect and intersect but with no meaning. We lost our ability to communicate intimately.

In the text, “Dhat” is referred to as a broadcasting machine. She is referred to through a part of her body, for she is an ass that grew bigger over time from her repeated recourse to the bathroom to cry. The expression “broadcasting machines,” which meaning both the writer and the reader agree on throughout the novel, refers in particular to Dhat’s female colleagues and her boss in the archive. In fact, each of them have a specific mask established and rooted within the text, such as (the rabbit's face) (and the broad-shouldered woman) and (the black mole) and (the clawed chief).

In light of this alienation, we are left with a satirical and a highly complex style that feeds our desire to complete the fictional aspect of the novel. The writer also uses artistic ploys to maintain the element of suspense.

Occasionally, he gives us readers new keys that were not mentioned before in the text, raising our ambitions to break the code and understand what those keys signify. After a series of complications, he satisfies those ambitions to illuminate new ones, and thus maintains the element of suspense throughout the novel.

The novel balances its fiction and documentary sides that show its broader meaning, where fictional characters move and live within the material historical events of the period. The movement of characters within this context explains and artistically justifies their nature and behaviour. In fact, characters in the fictional event represent an inevitable and natural development of the inequities in society narrated through the documentary or historical element of the novel, as both fiction and history interact with and enrich one another.

With the writer, we mock and laugh at the characters, but deep down within our laughter something bitter and painful remains. It is something that reminds us of the danger of slipping into this polluted space concerned with the fates and paths of these fictional people.

- 1. Adab wa Naqd was established in 1984 in Cairo by Al-Tagamo’ party. The magazine publishes literature and literary critique, as well as interviews with artists.

- 2. Mehrez, Samia 1994, Egyptian writers between history and fiction, Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 131.

- 3. Beddie, Melanie, and Peta Tait 2012, “Embodied exploratory processes in Australian performance training and international influences,” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 12,1: 5-19.