Two Revolutions in One | Sudan

Revolutionary

“How could I possibly demand the overthrow of a political regime while suffering from a repressive regime in my own home?” This is how my friend described the Sudanese women’s revolution while reminiscing on the demonstrations. She described how she and her friends were confronting the regime of the family even before Al-Bashir’s regime. She added, “I should have overcome this power.”

The patriarchal system and its influence on the regime of the family are closely related to the repercussions of political repression. This was made evident after a woman who was involved in the recent negotiations process amid the fall of the regime publically complained. She explained that she was always confronted with one of the negotiators saying things like: “you are a girl; have some respect for the opinion of elderly men,”. Regardless of the fact that both women and men were aware of the current political occurrences, women, however, are more aware of the circumstances. Women were on the streets every day, as they have effectively and regularly participated in the demonstrations, and played important and crucial roles in the Military Headquarters sit-in.

My other friend said, “it was a critical moment when my fear of being beaten by my dad was broken. So as long as the al-Kajir Forces will beat me during the demonstrations.” Al-Kajir is what the Sudanese Security Services and anti-riot police are called; their main task is to repress demonstrations and arrest demonstrators.

The Sudanese Revolution broke out against the Islamic Front, known as al-Inqath (The Rescue) in December 2018, following popular demonstrations against the price of bread and a shortage in fuel and cash in banks. The protests quickly developed into demands to overthrow the regime, due to people’s despair and unfulfilled promises to achieve economic stability. The country was already suffering from economic sanctions since 1983 when it was unable to pay its debts. In addition, in 1993, Sudan was put on the list of countries that sponsor terrorism, after it hosted al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden. Despite his departure from the country in 1996, Sudan was kept on the list because of several consecutive local events. The protest resulted in the fall of the Inqaz regime in April 2019.

With the celebrations of the anniversary of the glorious revolution in December, I believe the policy and authority of repression and patriarchy in the Sudanese society are what united most Sudanese women during the revolution. The patriarchy is deeply rooted in both social culture and the culture of the family under the guise of maintaining honor. It relies on systemic laws that are adopted by the state in its discrimination against women. An example would be the personal status law and the general system law. This guise affects all aspects of women's lives, including education, academic development, and promotion. Add to that not having the right to choose a job without the approval of both the nuclear and extended family. In fact, even when approved, women work under very stringent patriarchal conditions in the workplace. A woman’s success solely depends on marriage and child-bearing rather than her career. If a girl does not reach them as early as possible, she is shamed for being a “spinster.”

Despite the contradiction between the notion of revolution and the principles of honor, the latter often rules the fate of female revolutionaries. For the sake of irony, the revolutionaries celebrated the role of women in the revolution by chanting a “zaghrouda” at the beginning of all of the demonstrations to publicly declare the protest. Another chant says, “stay steadfast, girls, this revolution is the revolution of girls.” Despite that, the double standards were apparent during the revolution, including other chants that discriminate against women, such as:

“Behold Bashir, step back

You cannot defeat our revolution

The son of women, step back”

“Thirty years without gain.

We’ll marry you to Wedad, and bring her to you”

These chants revealed social stigma on two levels. First, they insulted their enemy by their social status and reproductive function, i.e., their ability to bear children. The overthrown president was always stigmatized for being impotent and never having children during his entire reign despite having married two women. Secondly, I saw the chant as a way to justify the rape of women who are considered to be an enemy, while portraying the revolutionary man as virile enough to fertilize her.

Reactions to these chants were swift and immediate. Young and old women would immediately correct the chants and would sternly and definitively warn against undermining the status of women, even if it were under revolutionary fervor. These brave confrontations were met with extreme sarcasm at first, but later, the rebels became aware of the importance of being considerate in their use of words in chants, as this is, ultimately, a revolution of anger and awareness.

Another chant was born in the Military Headquarters sit-in and still persists:

“This barricade cannot be broken; men stand behind them.”

The barricades are a shield that the rebels made out of bricks, cars, and heavy objects in order to protect the demonstrations and the sit-in areas from the security forces attacks. Despite the fact that the rebels built the barricades together to protect both women and men, the chant that they used to encourage people building them reduced courage and strength to men only. Women corrected this chant, saying:

“This barricade cannot be broken; rebels stand behind them.”

I remember the 8th of Ramadan massacre in the Colombia area, an area on the lower Nile riverside where cannabis and local drinks are sold. It was repeatedly accused of being a hub for drug trade. At the time, the Sudanese Professionals Association published a shameful statement delineating the borders of the sit-in excluding the Colombia area. This was clearly undermining the people of that area and the role they played in protecting the sit-in and the martyrs who used to be there, only because they were stigmatized for issues that society did not accept, such as being under the influence of substances. When the security forces attacked the Military Headquarters sit-in from Colombia, my friends and I were dislodging bricks off the pavement to build a barricade. At the time, one of the rebels insisted that we, as women, should carry fewer bricks, as per our “capacity.” I was so furious that I carried five bricks to prove my endurance, as I’ve always despised the prejudice that, as a woman, I am unable to do much, before I even tried.

I always remember the part of the revolutionary song “Live Ammunition” where the singer describes security forces snitches as “raw jugs who gossip like hair combers.” The word “raw” is said of a man accused of being gay, while “hair comber” refers to women who work in beauty salons and make African hair styles. The latter have been stigmatized as being gossip girls. This job is associated with poor women who lack the necessary skills to work in modern jobs, either for not being educated or due to their miserable economic situation. In both modern and rural societies, women work as cheap and unpaid labor in agriculture and construction. They also compose around 40 % of the unregulated work sector, such as food and tea vendors.

“Leave, leave, we don’t want you. The Kandaka (Queen mother) is more manly than you”

Due to a lack of awareness of the sensitivity of language and society’s constant justification of discrimination and gender-violence, some women repeated these chants too.

During the 3rd of June massacre at the Military Headquarters sit-in, rape was one of the weapons used, besides murder, against both sexes, predominantly women. Insults to female rebels and sexual and psychological assaults were all used as ways to punish women for participating in the sit-in.

“Did you not say you were a girl, you Kandaka, you divorcee” was one of the phrases that regime’s forces used to insult women, alongside “these Kandakas who sat in the square are for the adultery of slaves,” among other offensive and racist phrases that bear social and sexist stigmas. According to the testimony of one of the survivors, these were the phrases used during rapes, in addition to whipping women on their private parts.

What happened afterward was the worst. As a result of the social stigma, survivors did not reveal their identities. They were unable to even file official reports to hold the perpetrators accountable. Despite this, several of them are still being blackmailed by the Janjaweed Forces, who either threaten them with rape or spread the news that they were raped.

During this painful chaos, the Forces of Freedom and Change and the Transitional Military Council agreed on a transitional constitution, without amending the 40 % ceiling on the number of women. The social response was that “this is not the time, you women provided no martyrs.” This clarified the difference in importance given to martyrdom and sexual violations against women. The social violence continued, especially by families that found out that their daughters were attending the demonstrations or had attended the sit-in. Women are still facing social repression that is justified by being unintentional and internalized by the social unconscious.

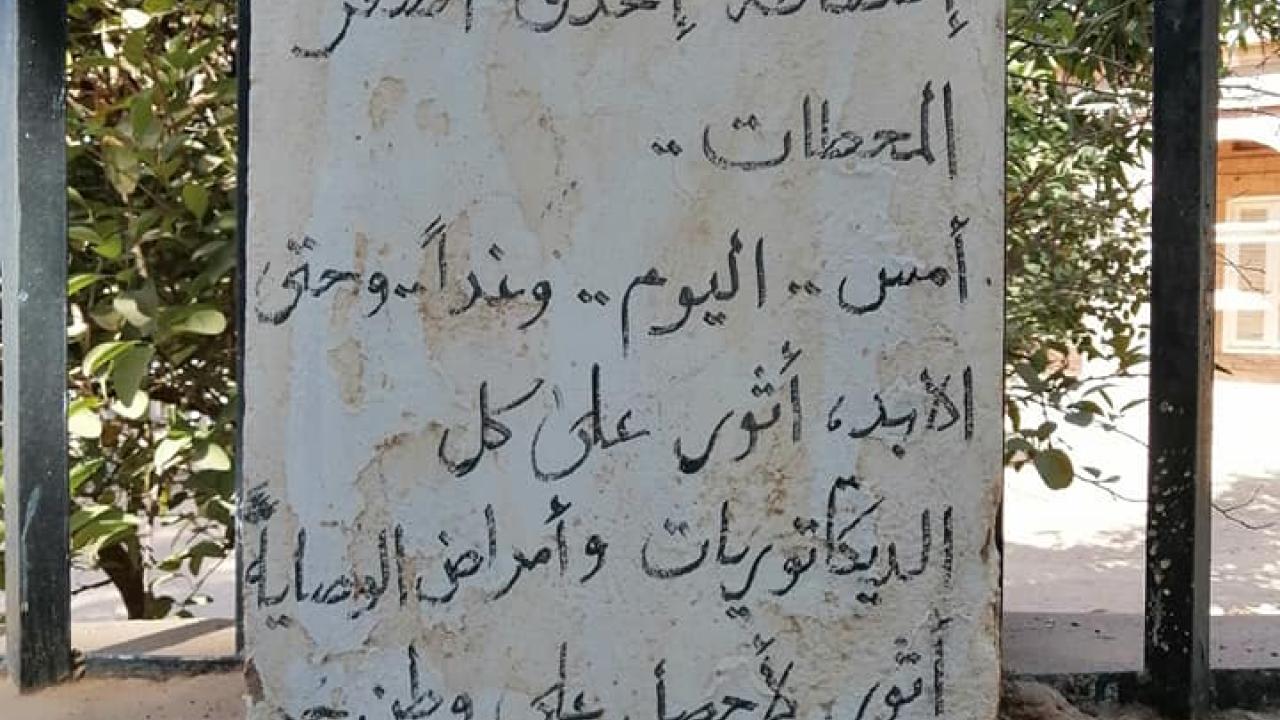

In the 1st commemoration of the massacre that broke the Military Headquarters sit-in, I remember writing on the walls of Klink Street:

“My revolution was not only against al-Bashir, that was but one of our minor stops

Yesterday, today, and tomorrow, I will always rebel against all dictatorships and stigmas

I rebel for a free nation where I can be free forever.”

The road is still long and full of barricades against women. As one of my friends said, our revolution is a revolution of rage, and this rage is still boiling.