Poverty Porn and Reproductive Injustice: A Review of Capernaum

ep3.png

“This is what they tell me when you talk to them, and I used to ask them are you happy to be alive? And most of them used to tell me no, why am I here? I didn’t ask to be here.”

Nadine Labaki, in an interview with Hammer to Nail1

Not much time was needed before Nadine Labaki’s film, Capernaum, became an international sensation deemed feminist and groundbreaking. The undeniably talented Lebanese director is one of few women who were able to seep through the cracks of the elitist and competitive cinematographic field and make it into the world of prestigious nominations and awards. Perhaps it is because Labaki is one of those same elite for whom the system is catered. Perhaps her work is granted such rare access as token of women’s labor. Or perhaps she is that exceptional “success story” that confirms the patriarchal exclusion rule. But regardless of the causes, writing this review comes with a lot of considerations. Criticizing women’s work in a world incognizant of our labor and genius makes us more vulnerable to its silencing structures. Criticizing the manifestation of one instance of liberalism could jeopardize other more radical efforts, so long they are crammed together under what became of the label of feminism due to mainstreaming efforts: a shallow signifier for women’s engagement in public life. A denunciation of Capernaum’s content can be easily appropriated and weaponized by trolls and misogynists against feminist causes. But this review is not for them. It is for us to imagine what conversation the film could have started, had it not inquired “are you happy to be alive?” and focused instead on “who is responsible for this misery?” The questions we ask are of considerable importance as they inform the action we partake in to address the issues at hand.

Capernaum sheds light on what the director is “obsessed with at the moment:”2 the poor and paperless. Admitting the nature of her interest, Labaki indulges in the whitewashing of racist, classist, sexist, and nationalist Lebanese complicity with structural barriers to justice that women, migrants, and refugees face. She tells a tale of all “the wretched of the earth” stripped from the disparities among them to create one category of the “poor.” The main character, Zain, is portrayed as socially-aware for carrying a discourse detached from the implications of belonging to his family, class, and community, all homogenously painted in the film. He is singled out by his refusal of his sister’s child marriage, as she is “not a fruit that can ripe.” The film opens with Zain suing his impoverished parents for giving him life. His access to court was granted by a surrealist turn of events, when he calls a Lebanese TV show from the juvenile prison in Roumiyeh, where he is serving a sentence for stabbing his brother-in-law. The central conflict is thus among the marginalized themselves: Zain and his family.3 The TV show becomes his liberation ticket, as his case is picked up by a lawyer, played by the director herself, who assists him in achieving a piece of justice by issuing him documents.

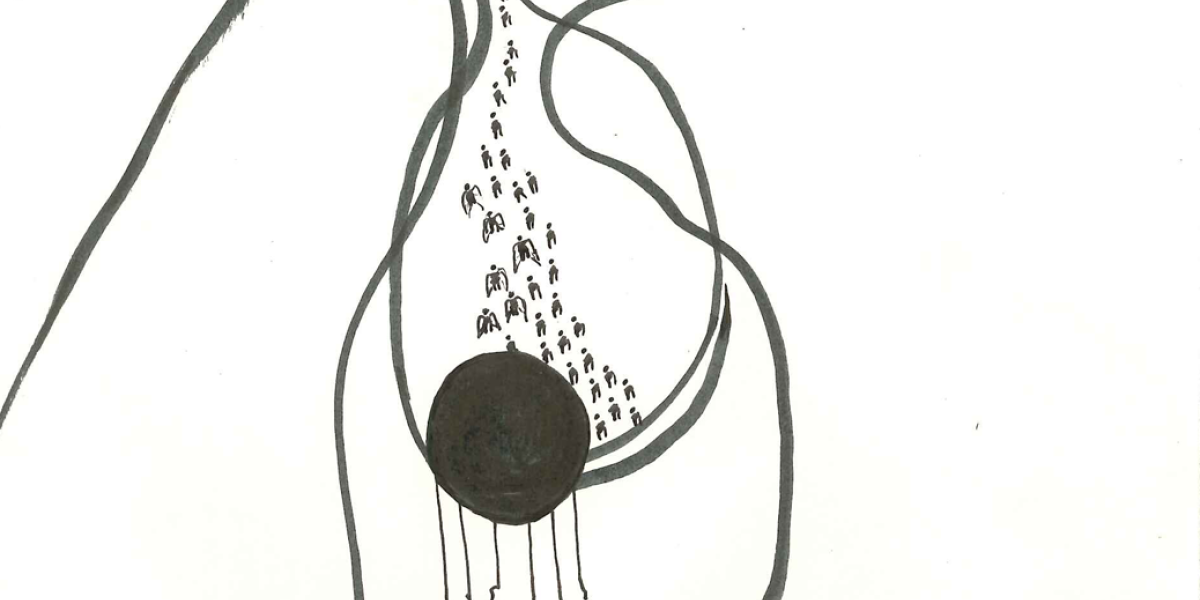

However, justice does not come in bits and pieces, a major truth that the film purposefully overlooks. Precariousness submerges the lives of the characters; socio-economic injustice is explicitly present but decontextualized: it is not imputable to anyone other than the poor themselves, abstract, and static. It is almost as if this poverty pornography shows overt content of marginalization, oppression, and persecution, to stimulate the pleasure organs of the Bourgeoisie and the state institutions and provide them with some form of catharsis. They would leave the cinema as they would a purgatory, washed off from their own guilt, complicity, and social responsibility, after “suffering” through the portrayals of misery.

The blurred lines between fiction and documentation strip the characters from credibility and protect the director from criticism. Granted, people living under poverty and oppression are not a product of imagination; yet, claiming the plot to be reflective of a “true story,” empty of imaginative acts, exempts Labaki from accountability in relation to the message produced. The director was acting, but “everybody else was playing their role.”4 A purposeful conflation is created: as the characters are not actors but real people, the responsibility for the overarching message of the film is placed on the poor. It is thus Zain who calls for demographic control policies aimed to deny childbirth to his community, and it is the street children who wish they were never born. It is everyone but the classist gaze of the upper-echelon of a society that desires to solve poverty by eradicating the poor.

On Sex, Motherhood, and Profanity

In the middle of their small and messy rooftop room that resembles a henhouse, Zain’s parents have sex behind a curtain separating them from five children attempting to sleep on one mattress. Zain is awake, looking over his siblings as they sleep, unsuspecting of the impudence happening a few centimeters away. The prodigy child acts as his sibling’s guardian while sex is portrayed as what distracts his parents from their parental duties. Zain knows full well what is happening and he seems annoyed, for sex, in Capernaum’s world, seems to be a luxury reserved for those who can afford rooms of their own. The film tells us that pleasure is not something the poor are entitled to, that it should not be readily available, for when it is, it is disgusting and wrong. Instead of being understood as an accessible “form of entertainment” that is available for all, should they want it, “sexual pleasure is seen as a luxury.”5 Then again, it is not merely the act of sex that is frowned upon, but its alienating quality as well. The sex we hear is not one we would like to have. Aside from the parents’ “perverted audacity” that enabled them to fuck in a room full of children, the sex we are eavesdropping on sounds technical and pleasure-less. We hear the man’s grunts and thrusts, whereas his wife’s voice is absent. Capernaum tells us that the sex of this generic category of “the poor” is unworthy of a social justice plight, as it does not resemble emancipatory tales of embracing desire and intimacy. Instead, it is technical, dutiful, and vulgar.

When had in this film, sex only disturbs the sleep of innocent children, brings additional mouths to feed and criminals to imprison, and gives life to undocumented half-breeds. One of them is Yonas. He is the result of the “mistake” of Rahil, an Ethiopian migrant domestic worker, and a janitor we see in passing. What is qualified as a mistake is not a late pull-out practice or a non-consensual ejaculation. It is the relationship itself. Rahil explains to the judge that she got pregnant and escaped her employer, dooming herself to a life of shame and precariousness. As a migrant worker who is ticked on the clock since the moment she arrived to Lebanon, she is not entitled to any form of human relationship or interaction. Her function is one – that of a laborer, underpaid and exploited. Her body and time are not to serve anything other than low-waged domestic labor. There is no discussion of the systemic violence and barriers migrant domestic workers face – just the mention of an individual mistake. “Madam was good to me,” Rahil says, because her misery is the fault of no one other than herself. It is personified in Yonas, whose blackness provides the “comic relief” in a torment-charged plot. Attempting to explain Yonas’ skin color when posing as his brother, Zain indulges in racist commentary, one that is “dismissible” on the account of his childhood and innocence. An excessive coffee intake while pregnant or a temporary condition washed off by age are excuses provided for this imagined kinship. It appears that the superior Lebanese “race” does not mix, so a black brother to a child of color is inconceivable to the minds of simple mortals. It borders on science-fiction.

Similar to Rahil getting the blame for the systemic violence she and her child experience, there is a free-pass at Zain’s mother. She is held accountable by both the (in)justice system and her 11-year-old pseudo-woke son. Zain puts his mother through trial literally and metaphorically: he drags both his parents to the court room, but it is his mother alone who is accountable for pregnancy. The father, conversely, is victimized: he did not want any of this but did not know any better. He was told that manhood meant a large family and now he is bearing the weight of breadwinning. He was told that when a child comes, he/she would bring enough wealth with him/her to secure his/her subsistence. The statement is reminiscent of the “God help you” with which one “politely” declines offering money to beggars. The richer person delegates responsibility to god, despite being approached. The father is a simple man who fell for the esoteric promise, but the mother is taking a bigger chunk of the blame. She is vicious, using her children to access material goods at the expense of their health and childhood. She sees her children incarcerated and dead, and yet she keeps on having more.

In this pit infested with irresponsible parents, insatiable sex, and negligent reproduction, where family communicates through violence, verbal and physical, even their “brightest” child uses profane language in his daily communication and play. Zain is detached from his family’s customs in almost every imaginable way. However, no matter how rebellious he is, he reproduces their language, revealing his class: he cannot complete a sentence without using slurs. The degeneracy of his family makes itself heard and is almost unescapable. So while portraying the dissonance between Zain’s ideals and those of his community, Capernaum still reinforces the exclusivity of “proper” communication to a higher social class. Zain remains a prisoner of language: washed off from the dirt that accompanies his face throughout the film and dressed in new clothes at the court-room, he is cheated by his tongue. Similar to the supremacist gaze confinement of black people’s tongue to ebonic, the Bourgeois gaze cannot conceive of a world where Zain can speak without slurs.

On Reproductive Quantitative Solutions

The film proposes a quantitative solution to “paperless children” who are “growing by the millions now.”6 Labaki states that “there’s no specific statistic […] because they don’t want to acknowledge the problem, but the problem is huge,” further insisting that it is proportional to the number of poor children populating this country. While the movie does not advocate for the forced sterilization of the poor, liberal audiences might come out of it puzzled: how many poor children are too many? Completely denying these women motherhood is not an attractive prospect for liberal minds, but putting a limit on the number of children they can have seems plausible. Zain, the Bourgeois voice in proletarian clothing, asks the judge whether his mother’s pregnancy can be stopped. It is not a quest for access to abortions, but an articulation of the impasse his family reached. The mother is already pregnant and there is nothing to do about it. And if there was, it is a decision in the hands of a male judge or the Lebanese government because our bodies and access to services are at the disposal of men in power. Even if Capernaum made an explicit argument in favor of legalizing abortion, the rationale would have remained the same: the poor should not reproduce.7

The freedom the movie took to allude to the question of limiting the number of marginalized people’s children is appalling. Such a question is a mind-fuck on its own: it echoes the Bourgeois entitlement to control the reproductive function of sexualized and racialized bodies. The working class and economic disparity have to reproduce in parallel. However, they also ought to reproduce at a ratio and in a way that uphold other structures of oppression and systems of othering. What “interracial” children are to “white purity” is what those of mixed sectarian background are to Lebanese consociationalism, and those transnational are to nationalism. Henceforth, in terms of the state’s control over reproduction, all poor are equal but, some are more equal than others:8 certain people are asked to have less children and other no children at all, unless they can be had in secret, stripped from rights, dignity, and access to goods and services.

Consequentially, Rahil should neither be a birthing mother nor a sexually active woman: the Kafala system allows her zero children. Refugees can have a few – provided they are born elsewhere and do not disturb the peace of the citizens by existing in schools, jobs, and even streets. When the state is implementing a policy of forced return of migrants and refugees, purposefully refusing to give them legal ground for subsistence so they cannot live or die, get medicated or educated or employed, or start families, they have no choice but to leave. Many die at the doorsteps of hospitals because they do not have proper documentation, to which a fake-concern exclaims: “but why do they have to keep on having so many children?!” The heteronormative reproductive role is only natural to well-off Lebanese, but it loses its normalcy when the citizens are “outnumbered” or “feel like refugees in their own country.” It is ironic, then, that the character chosen to die of a pregnancy-related hemorrhage at the doorsteps of a hospital due to the lack of documentation is Lebanese. Zain’s sister, Sahar, meets that end, once again due to the negligence of her parents.

Nationality does not manifest itself as a difference among the poor of Capernaum, unless it is to compete over privileges. Maysoun, a Syrian girl, recites a nationalist annoyance of a nation to which she does not belong: she tells Zain that unlike her, he cannot apply for asylum. “Lebanon is not for the Lebanese anymore!” The xenophobic motto comes to life, and receiving any kind of support, human decency, or illicit exploitative employment after fleeing a war becomes a matter of competition. Instead of discussing compulsory and denied motherhood, the right to determine how many children a woman wants to have, the right to access contraception and healthcare including safe and affordable abortions, the film cries out: couldn’t they just have kept their legs closed instead of fucking like rabbits?

On Crime and State

Carefully handpicked to be neutral in confession, the names of the central characters contribute to the erasure of the sectarian context and the homogenization of the poor. Lebanon appears ahistorical and empty of the sectarian, social, and political basis of organizing. The Bourgeoisie appears compassionate, although unaccountable for social disparities and disengaged from networks of patronage and clientelism.

Unaccountability is present both in the content and delivery of the movie: it is Zain who makes the strongest allegations against his mother. The film refuses to share its message, judging the poor for having children, on the tongue of those who would most likely voice them. Instead, when the subaltern speaks, he parrots the state’s discourse. When his mother announces her pregnancy, Zain tells her that the future child, like him, is condemned to a life of poverty and crime. For crime, in this movie, is exclusively used to denote the practices of the poor. Conversely, the actions of men in power, such as gate-keeping access to services and criminalizing rights to healthcare, decent life, and entire existences, are expressions of law and order.

We witness multiple crimes in this film: underprivileged children’s engagement in illicit trade, non-citizens’ presence within the Lebanese territory without supporting documentation, migrant worker’s sexual activity and reproduction, etc. The state’s scrutinizing of resources is not one, and neither are its rampant xenophobia and racism, or its reproduction of the nation through absence of personal status laws and criminalization of abortion among other demographic policies.

Capernaum assists the state-building production of a homogeneous “social body,” where processes are predictable and therefore controllable. It creates a distinct, one-dimensional category of the “poor,” especially at the intersection of poverty and womanhood. It disciplines their bodies, upholding that of the state: Rahil and her child get deported while Zain’s mother – who did not deserve a name – is judged for failed motherhood and humanity. The state meddles in her pregnancy, echoing a larger biopolitical control over life-spans and expectancies, as well as the production and circulation of wealth. Nation building takes place on her body; her uterus becomes a factory and her vagina a battlefield. Women’s bodies are essential for state-building, for they are a pivot from the individual to the species through the sexual and reproductive apparatus. So long childbirth happens through our bodies, we are to be on the receiving end of collective discipline by virtue of our assigned gender, and individual blame for failures at motherhood. Racialized, sexualized, gendered, and marginalized, we become liable for our misery, and we are told to pull ourselves from our bootstraps.

Positionality is absent from Capernaum, and the poor are scrutinized like parasites under a microscope. They are out to opportunistically benefit from systems of charity and aid, sending their sons to school for bags of rice, not for an education, and marrying off their child-daughters in exchange for three chickens and instant noodles. The movie frees higher classes from responsibility in economic disparities upon which they thrive, and exempts the state from any kind of criticism. If anything, the state emerges as the savior. It listens to the plight of the poor insofar it is conductive to the control of their reproduction. It issues Zain the papers his parents neglected. It returns Yonas to Rahil so as they can be mother-and-child elsewhere, away from Lebanon. While painting the state in general, and the general security in particular, in a positive light guaranteed Capernaum’s swift passage through measures of censorship, it also contributed to the reproduction of governmental propaganda and control, and the legitimization of liberal impunity. The movie focused the conversation on the “bad parenting,” “bad motherhood,” and “bad sex” that the poor engage in, thereby afflicting a category of people it was set to represent. The overt content opportunistically portrays the degrading realities of life of those marginalized, subjecting them to our gaze. It is about them, but not by or for them as the movie would like us to believe. Instead, it caters to the liberal fantasies of a classless world free of disparity – a Darwinist world where there is no poverty because natural selection failed those unable to pull themselves from their bootstraps. Capernaum is not chaos; it is liberal dystopia.

- 1. All the Nadine Labaki quotes in this review are from Christopher Llewellyn Reed’s interview with her, published in Hammer to Nail on October 1st, 2018, and available at: http://www.hammertonail.com/film-festivals/nadine-labaki-interview/

- 2. Ibid.

- 3. Ahmad Mohsen’s “Capernaum from above and below: a Bourgeois Portrayal of the State?” published in Al-Akhbar on October 1st, 2018, and available at: https://al-akhbar.com/Cinema/258855

- 4. Footnote 1.

- 5. Rola Yasmine’s talk on AUB’s Human Rights Day Panel titled “Sexual Rights are Human Rights: What about Pleasure?” available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ASx9Xs21LYQ&t=3277s, starting minute 38:00.

- 6. Footnote 1.

- 7. It is reminiscent of the state’s dual stance on abortion: While illegal, the system overlooks some instances to accommodate the rich on one hand and to limit the reproduction of migrants and refugees on the other. The topic is discussed at length by Maya Ammar in a video by Daraj, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6agCzctczZc

- 8. A play on George Orwell’s “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others,” from Animal Farm.